Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Where did you get those shoes?: Storytelling for landscape photographers

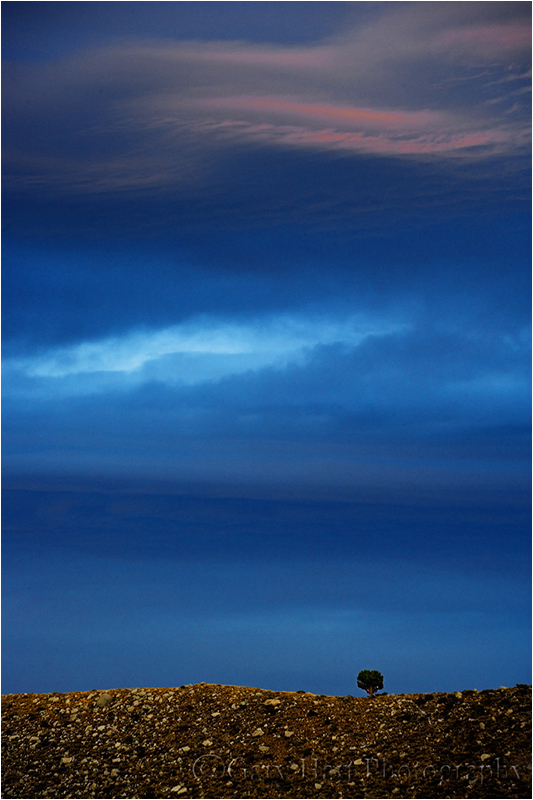

Tree at Sunset, McGee Creek Canyon, Eastern Sierra

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

1/40 second

F/7.1

ISO 400

126 mm

Let’s have a show of hands: How many of you have been advised at some point in the course of your photographic journey to “tell a story with your images”? Okay, now how many of you actually have a clue as to what that actually means? That’s what I thought. Many photographers, with the best of intentions, parrot the “tell a story” advice simply because it sounded good when they heard it, but when pressed further, are unable to elaborate.

Telling a story is more easily accomplished in the photographic forms that allow photographers to arrange scenes and light to suit their objective (an art in itself), or journalistic photography intended to distill the the essence of an instant in time: a homeless man feeding his dog, dead fish floating in the shadow of belching smokestacks, or a wide-receiver spiking a football in the end zone.

This isn’t to say that landscape photographers can’t tell stories with our images, or that we shouldn’t try. Nor does it mean that one photographic form is inherently more or less creative than another. It just means that the rules, objectives, advantages, and limitations are different from form to form. Nevertheless, simply advising a landscape photographer to tell a story with her images is kind of like a coach telling a pitcher to throw strikes, or a teacher instructing a student to spell better. Okay, fine—now what?

Finding the narrative

First, let’s agree on a definition of “story.” A quick dictionary check reveals this: A story is “a narrative, either true or fictitious … designed to interest, amuse, or instruct….” That works.

The narrative part is motion. Your pictures need it. Narrative motion isn’t the visual motion of the eyes through the frame (also important), it’s a connection that pulls a viewer into a frame and compels him to stay. While narrative motion happens organically in media consumed over time, such as a novel or a movie, it can only be implied in a still photograph. And unlike the arranged or journalistic photography forms I mentioned above, landscape photographers are tasked with reproducing a static world as we find it—another straightjacket on our narrative options. But without some form of narrative motion, we’re at a dead end story-wise. What’s a photographer to do?

Photography as art

Every art form succeeds more for what happens in its consumer’s mind than for what it delivers to the consumer’s senses. Again: Every art form succeeds more for what happens in its consumer’s mind than for what it delivers to the consumer’s senses. A song that doesn’t evoke emotion, or a novel that doesn’t paint mental pictures, is soon forgotten. And just as readers of fiction unconsciously fill-in the visual blanks with their own interpretation of a scene, viewers of a landscape image will fill-in the narrative blanks with the personal stories the image inspires.

Of course the story we’re creating isn’t a literal, “Once upon a time” or “It was a dark and stormy night” (much more effective in photography than literature, I might add) story. Instead, the image we make must connect with our viewer’s story to touch an aspect of their world: revive a fond memory, provide fresh insight into a familiar subject, inspire vicarious travel, to name just a few possible connections. If we offer images that tap these connections, we’ve given our image’s viewers a reason to enter, a reason to stay, and a reason to return. And most important, we’ve given them a catalyst for their internal narrative. Bingo.

Shoot what you love

Think about your favorite novels. While they might be quite different, I suspect one common denominator is a protagonist to whom you can relate. I’m not suggesting that immediately upon finishing that book you hopped on a raft down the Mississippi River, or ran out to have a dragon tattooed on your back, but in some way you likely found some personal connection to Huckleberry Finn or Lisbeth Salander that kept you engaged. And the better that connection, the faster the pages turned.

And so it is with photography: Our viewers are looking for a connection, a sense that there’s a piece of the photographer in the frame. Because we can’t possibly know what personal strings our images might tug in others, and because those strings will vary from viewer to viewer, our best opportunity for igniting their story comes when we share our own relationship with a scene.

What? Didn’t I just say that it’s the viewer’s story we’re after? Well, yes—but really what needs to happen is the viewer’s sense of connection between our story and hers. If you focus on photographing the scenes that most move you, those scenes (large or small) that might prompt you to nudge a loved-one and say, “Oooh, look at that!,” the greater your chance of establishing each viewer’s sense of connection. Whether you’re drawn to mountains, crashing surf, delicate wildflowers, or prickly cactus, that’s where you’ll find your best images.

But what about the shoes?

The cool thing is that your viewer doesn’t need to understand your story; he just needs to be confident that there is indeed a story. That’s usually accomplished by avoiding cliché and offering something fresh (I know, easier said than done). For some reason this makes me think of Steely Dan lyrics, which rarely made sense to me, but they were always fresh and I never for a second doubted that they did indeed (somehow) make sense. In other words, rather than becoming a distraction, Steely Dan’s lyrics were a source of intrigue that pulled me in and held me. So when I hear:

I stepped up on the platform

The man gave me the news

He said, You must be joking son

Where did you get those shoes?

I’m not bewildered, I’m intrigued. Donald Fagen’s lyrics aren’t trying to tap my truth, they simply reflect his truth (whatever that might be). And even though I have no idea what he’s talking about, the vivid mental picture Fagen’s lyrics conjure (which may be entirely different, but no more or less valid, than your mental picture) allows me to feel a connection. You, on the other hand, may feel absolutely nothing listening to “Pretzel Logic,” while “I Want To Put On My My My My My Boogie Shoes” might give you goosebumps for KC and the Sunshine Band. Different strokes….

Returning from the abstract to put all this into photographic terms, the more your images are true the world as it resonates with you, and the less you pander to what you think others want to see, the greater the chance your viewer’s story will connect with yours.

The story of this image

My own story of this image involved a frantic rush to capture a beautiful but rapidly fading sunset. I was with my brother on a dirt road in the Eastern Sierra. I’d been on this road many times and knew this tree well. Despite its rather ordinary appearance, the tree’s solitary perch atop a barren, rocky ridge had always intrigued me. I’ve always longed for a home with a sweeping view, and envied this tree’s perpetual 360 view of the Sierra crest to the west, the White Mountains to the east, and Crowley Lake below.

As the sunset started to materialize that evening, I realized that we were close enough that I might be able to include the tree in the sunset shoot. We hustled my truck back down the road, pulling into to a wide spot beneath the ridge several minutes after the best color had faded. Jay, who had no personal connection to “my” tree, stayed in the truck while I sprinted along the road with my camera and tripod until my position aligned the tree with the final, rippled vestiges of sunset. I only clicked a couple of frames, slightly underexposed to hold the color. (The slight blue cast is the color of the twilight light.)

That’s my story, and while it’s personally satisfying, I have no illusions that any of that comes across in the image. I’ve displayed this print in many shows and watched people walk right by without breaking stride. But I’ve also been pleased to watch many people stop, linger, and return. While I have no idea what “story” this image taps for them—solitude? conquest? perseverance?—I don’t think it really matters.

That song makes perfect sense. You can’t get on a train barefooted. After being informed of this by The Man on the platform, the lyricist obviously tried to board the train wearing something he improvised from fast food containers found in the trash.

As for the photograph, I love the way the pink clouds echo the contour of the landscape. Awesome.

Gary, There are so many things about your writeup, here, that I love. I completely agree with you in your discussion about finding the narrative. You pulled that notion from my mind that was floating around in the vast open abyss of my brain: that “telling” a story for street phtography, for instance, can be a heck of a lot different than “telling” a story for nature and landscape photags. I have long stuggled wit that “story” stuff. And all of it really comes together in “shoot what you love” and “the story of this image.” I think that the “connection’ we feel has to be something that is drawn from us or inspires us (any way you want to look at it) by something we see in that image – whatever it may be. The “succesful” image is one that can do that. YOU “get” that concept that s why your images always have something in them that moves viewers.I will stop becasue again I am taking way too much of the floor. But reading your words is as beneficial to me as the emotional and inspirational uplift that I and I know thousands of others get from your work. Thanks Gary 🙂

Thank, Denny, very well put. It really is all about the connection we create.