Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

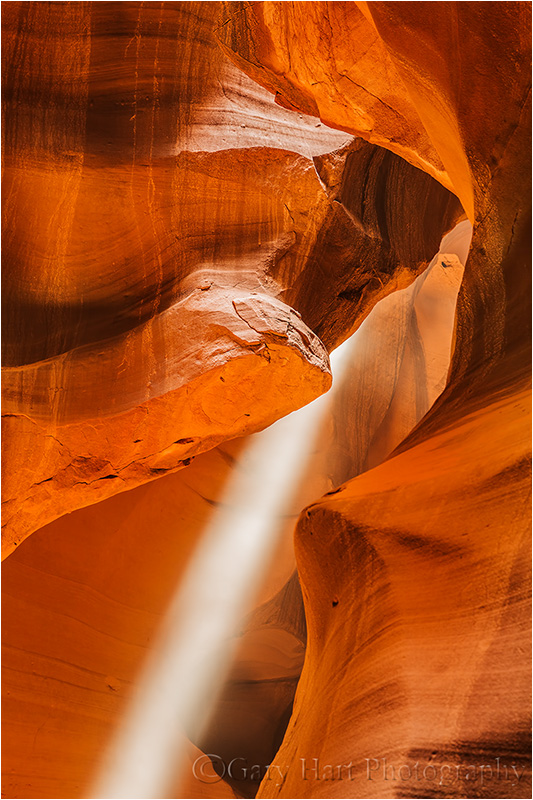

Light fantastic: A photographer’s guide to our most essential subject

Photograph: “Photo” comes from phos, the Greek word for light; “graph” is from graphos, the Greek word for write. And that’s pretty much what photographers do: Write with light.

Good light, bad light

Because we have no control over the sun, nature photographers spend a lot of time hoping for “good” light and cursing “bad” light (despite the fact that there is no universal definition of “good” and “bad” light). Before embracing someone else’s good/bad light labels, let me offer that I (and most other professional photographers) could probably show you an image that defies any label you’ve heard. The best definition of good light is light that allows us to do what we want to do; bad light is light that prevents us from doing what we want to do.

Studio photographers’ complete control of the light that illuminates (an art in itself) their subjects allows them to create their own “good” light. Nature photographers, on the other hand, rely on sunlight and don’t have that luxury. But knowledge is power: The better we understand light—what it is, what it does, and why it does it—the better we can anticipate the light we seek, and deal with the light we encounter.

The qualities of light

Energy generated by the sun bathes Earth in continuous electromagnetic radiation, its wavelengths ranging from extremely short to extremely long (how’s that for specific?). Among the broad spectrum of electromagnetic solar energy we receive are ultraviolet rays that burn our skin (10-400 nanometers), infrared waves that warm our atmosphere (700 nanometers to 1 millimeter), and the visible spectrum—the very narrow range of wavelengths between ultraviolet and infrared that the human eye sees, in the wavelength range between 400 and 700 nanometers.

When all visible wavelengths are present, we perceive the light as white (colorless). But when light interacts with an object, the object reflects, absorbs, and scatters the light’s wavelengths. When light strikes an opaque (solid) object such as a tree or rock, characteristics of the object determine which of its wavelengths are absorbed; the wavelengths not absorbed are scattered. Our eyes capture this scattered light, send the information to our brains, which translates it into a color.

When light strikes water, some is absorbed and scattered by the surface, enabling us to see the water; some light passes through the water’s surface, enabling us to see what’s in the water; and some light bounces off the surface, enabling us to see reflections.

Let’s get specific

Rainbows

For evidence of light’s colors, look no farther than the rainbow. When light enters a raindrop (or any other drop of water), characteristics of the water cause the light to bend slightly. Because different wavelengths bend different amounts, a single beam of white light is separated into its component colors as it passes through the raindrop. When the separated light strikes the back of the raindrop, it reflects, with different wavelengths (colors) returning at slightly different angles: a rainbow!

Blue sky

White sunlight reaches Earth, the relatively small nitrogen and oxygen molecules that are most prevalent in our atmosphere scatter the shorter wavelengths (violet and blue) first, turning the sky blue. The longer wavelengths (orange and red) continue on to color the sunset sky of someone farther away.

The more direct the sunlight’s path to our eyes (the less atmosphere it passes through), the less chance the longer wavelengths have to scatter and the more pure the blue wavelengths. So when the sun is high in our sky, its light takes the most direct path through the atmosphere and our sky is most blue (all other things equal). In the mountains sunlight has passed through even less atmosphere and the sky appears even more blue than it does at sea level.

On the other hand, when relatively large pollution and dust molecules are present, all the wavelengths (colors) scatter, resulting in a murky, less colorful sky (picture what happens when your toddler mixes all the paints in her watercolor set).

Most photographers (myself included) find homogeneous blue sky boring. Additionally, when the sun is overhead, bright highlights and deep shadows create contrast that cameras struggle to handle.

Sunrise, sunset

Remember the blue light that scattered to color our midday sky? The longer orange and red wavelengths that didn’t scatter overhead, continued on. As the Earth rotates, eventually our location reaches the point where the sun is low and the sunlight that reaches us has had to fight its way through so much atmosphere that it’s been stripped of all blueness, leaving only its longest wavelengths to paint our sunrise/sunset sky shades of orange and red.

When I evaluate a scene for sunrise/sunset color potential, I look for an opening on the horizon for the sunlight to pass through, pristine air (such as the clean air immediately after a rain) that won’t muddy the color, and clouds overhead and opposite the sun, to catch the color.

Overcast and shade

Sunny days are generally no fun for nature photographers. In full sunlight, direct light mixed with dark shadows often force nature photographers to choose between exposing for the highlights or the shadows (or to resort to multi-image blending). So when the sun is high, I hope for clouds or look for shade.

Clouds diffuse the omni-directional sunlight—instead of originating from a single point, overcast light is spread evenly across the sky, filling shadows and painting the entire landscape in diffuse light. Similarly, whether caused by a single tree or a towering mountain, all shadow light is indirect. While the entire scene may be darker, the contrast range in shadow is easily handled by a camera.

Flat gray sky or deep shade may appear dull and boring, but it’s usually the best light for midday photography. When skies are overcast, I can photograph all day—rather than seeking sweeping landscapes, in this light I tend to look for more intimate scenes that don’t include the sky. And when the midday sun shines bright, I try to find subjects in full shade. Overcast and shade is also the best light for blurring water.

Leveraging light

Whether I’m traveling to a photo shoot, or looking for something near home, my decisions are always based on getting myself there when the conditions are best. For example, in Yosemite I generally prefer sunset because that’s when Yosemite Valley’s most photogenic features get late, warm light; Mt. Whitney, on the other side of the Sierra, gets its best light at sunrise; and I’ll only the lush redwood forests along the California coast in rain or fog.

Though I plan obsessively to get myself in the right place at the right time, sometimes Nature throws a curve, just to remind me (it seems) not to get so locked in on my subject and the general tendencies of its light that I fail to recognize the best light at that moment. If I drive to Yosemite for sunset light on Half Dome and am met with thick overcast, I don’t insist on photographing Half Dome. Instead, I detour some of my favorite deep forest spots, like Fern Spring or Bridalveil Creek.

Other times finding the best light is simply a matter of turning around and looking the other direction. Mono Lake is one of those places that reminds me to keep my head on a constant swivel, or risk getting so caught up on the sunrise in front of me that I miss the rainbow behind me.

About this image

On a rainy October afternoon in Yosemite, I did what I often do on rainy afternoons in Yosemite: hang out at Tunnel View, waiting (hoping) for the storm to clear. I’d circled Yosemite Valley in my car several times, but the clouds had dropped well below rim-level and obscured all of Yosemite’s recognizable features.

Yosemite’s clearing usually starts at Tunnel View, and when it happens in the afternoon, a rainbow is possible. But with sunset approaching and the rain showing no sign of relenting, I was losing hope. Anxious for something to do besides wiping the fog from my windshield and listing to rain pelt my roof, I decided to drive through the tunnel for a view to the west (toward the source of any clearing). Seeing nothing promising on the other side, I flipped a quick u-turn and headed back.

The roundtrip was less than five minutes, but I exited the tunnel to see that Half Dome had emerged from the gray muck sporting a vivid rainbow. I screeched to a stop and bolted from the car, changing lenses and wresting my tripod all the way to the vista. I got off just two frames before the light was snuffed, ending up with this image and a valuable lesson: You can’t predict what Yosemite’s weather will be in five minutes based on its weather right now.

(BTW, see that little white cascade trickling down El Capitan’s flank? That’s Horsetail Fall.)

Workshop schedule

Celebrating light

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

superb shot

Useful tips, thanks!

Thanks—you’re very welcome.

Pingback: Light fantastic: A photographer’s guide to our most essential subject | Brian Snyder Photography