Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

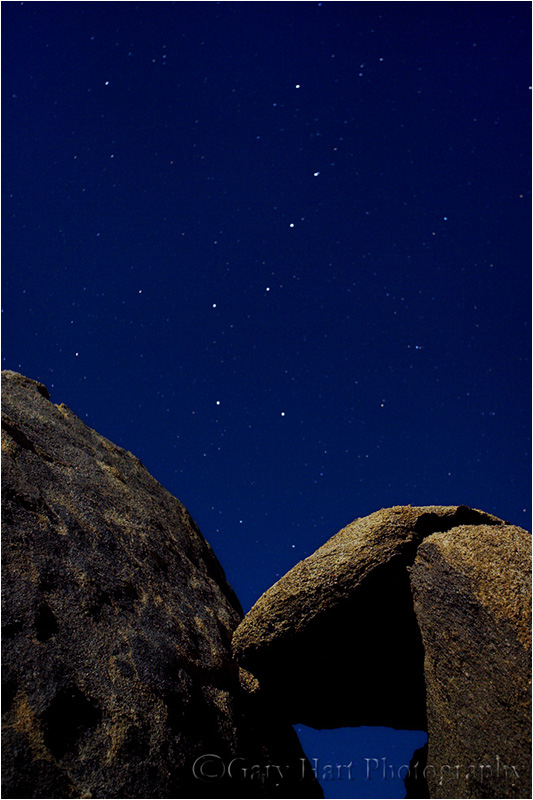

Favorite: The Big Dipper

Posted on August 6, 2013

I’ve decided to turn my new Favorites gallery into an irregular series on each of the images there.

* * * *

This image of the Big Dipper above moonlit granite boulders in the Alabama Hills will always have a special place in my heart because it was my first moonlight “success.” I was still coming to terms with the low light capabilities of digital photography, and figured that a full moon over the Alabama Hills might be a good opportunity to play. I was in Lone Pine with my brother to explore the endless daylight possibilities among the weather granite boulders just west of town.

Jay and I started that night by simply photographing the Sierra crest, anchored by Lone Pine Peak and Mt. Whitney, from the side of the road. It wasn’t long before I was confident that I had the exposure settings right (arriving through trial and error at the moonlight exposure recipe I still use), and we soon set out for less prosaic surroundings, ending up in a box canyon at the end of an obscure spur off (unpaved) Movie Road. All of my attention was on Lone Pine Peak and Mt. Whitney in the west, but while waiting for an exposure to complete, I noticed the Big Dipper suspended above the northern horizon.

I wish I could say this composition was divine inspiration fueled by my innate artistic instincts, but it was more of a casual click using a couple of anonymous boulders whose prime attraction was their convenience. Focus was tricky, and while I don’t specifically remember all my decisions, I know I must have realized that sharp foreground rocks trumped sharp stars (that would be moving slightly anyway). I’ve done enough moonlight photography since to know that while manual focus in the dark is difficult, it’s not impossible. Finding focus involves rapidly twisting the focus ring in decreasing concentric arcs around the point where the target “feels” sharp—subsequent experience has taught me that (for me at least) the results are usually better than I fear they are. And of course it doesn’t hurt that even at f2.8, 25mm gives me quite a bit of depth of field.

I remember thinking when the image popped up on the postage-stamp LCD of my 1D Mark II, “That’s pretty cool.” But I couldn’t have been too impressed because I only took two frames before returning to the (ultimately forgettable) Sierra compositions. The next memory I have is looking at my images on my laptop later that night—it was quite clear that this image was my favorite, by a long-shot, and I wished I’d have tried more. I’ve tried unsuccessfully to find these boulders on subsequent visits, but I haven’t given up. I can’t even say that I’d photograph them again, but I’d at least love to see them once more.

Category: Alabama Hills, full moon, Moonlight, Photography, stars Tagged: Alabama Hills, moonlight, Photography

Later that same morning…

Posted on March 1, 2013

Moonset, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, California

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

24-105L

1/2 second

F/11

ISO 100

It’s fun to browse the thumbnails from a shoot in chronological order to see the evolution of that day’s process. While can’t always remember specific choices, it’s always clear from the progression of my images that I was indeed quite conscious of what I was doing. I can look at one thumbnail and usually predict what the next will be.

This January morning in the Alabama Hills started for me about forty-five minutes before sunrise. When the sun finally warmed Mt. Whitney, a 95% waning gibbous moon was about to dip below the Sierra crest; comparing images, it’s clear I’d moved no more than twenty feet from the location of that morning’s earliest images. This is pretty typical of my approach—unlike many (but not all) photographers, who actively bounce around a location in search of something different, I tend to seek the scene until I find it, then work it to within an inch of its life. If I’m moving around, it usually means I haven’t found something that completely satisfies me.

Is mine the best approach? Of course not, but it is the best approach for me. There is no all encompassing rule for workflow in the field, except maybe to be true to your instincts. Because I happen to be very deliberate in my approach to many things, and can be incredibly (obsessively?) patient when I sense the potential for something I want, that’s the way I shoot. But, regardless of changing conditions and possible compositional variations, some photographers would go crazy locking into one scene. And just as my deliberate approach continually reveals details I’d have missed had I moved on sooner, it sometimes cheats me of even better opportunities waiting just around the corner. But I learned a long time ago not to stress about what I might be missing (because for me it’s even worse to chase what’s around the corner only to find what I end up with doesn’t match what I left).

Early on this chilly morning I found a relationship between a nearby stack of boulders and the distant Sierra peaks (Mt. Whitney in particular); the more time I spent with the scene, the more I saw and the better all the elements seemed to fit for me, so I just kept working. It didn’t hurt that conditions were changing almost as quickly as I could compose. Clouds ascended from behind Mt. Williamson as if churned out by a cloud making machine, sprinted south past Mt. Whitney, and disappeared behind Lone Pine Peak. On their way they took on whatever hue the rising sun was delivering, from white (before the sun) to vivid pink to amber.

Comparing today’s image to the image in my previous post, I see that my composition shifted to account for the moon. In the earlier image the most prominent boulder and Mt. Whitney serve as a set that anchors the center of the frame. In the later image I keep the set together but offset them to the left to balance the moon’s extreme visual weight. And while at first glance it appears both images were captured from the same spot with just slight focal length and direction adjustments, the height and position of the foreground boulder relative to Mt. Whitney’s summit shows that I’ve moved a little left and about twenty feet closer.

Relationships between elements in a frame are essential to an image’s success—controlling these relationships is a matter of moving up/down, left/right, forward/backward. Without remembering my decision to move that morning, I can still reconstruct my likely thought process: The more I worked the scene, the more clear I became on where the boulders’ left and right boundaries should be. Moving left and closer let me go wide enough to include the moon and clouds, fill the foreground with no more of the foreground boulders than I wanted, and balance the frame with the boulder/Whitney pair on the left and the moon on the right.

So while I do indeed stick with one scene for a long time, I’m far from static. Each frame is slightly different from the previous one. Like most of my favorite images, this Whitney sunrise moonset is an evolution; it started in the dark, evolving with the conditions and my growing familiarity with the scene’s elements.

There are no guarantees in nature, and I’ve had my share of “panic shoots” when something unexpected forced me to run around frantically searching for a scene to go with the moment. But when this morning’s dance of light, clouds, and moon blended into one of those magic moments photographers dream about, I was ready.

Photo Workshop Schedule

An Eastern Sierra Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Alabama Hills, Moon, Mt. Whitney, Photography Tagged: Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra, moon, Mt. Whitney, Photography

The secret world before the sun

Posted on February 24, 2013

Before Sunrise, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, California

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

30 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

70 mm

Compared to the human eye, the camera’s vision has many shortcomings (as photographers are quick to lament). At the top of photographers’ list is the very narrow gap separating the brightest and darkest tones a camera can capture: dynamic range.

But while the camera taketh away, it also giveth. Experienced photographers understand that what we perceive as complete darkness is really just our eyes’ relatively limited ability to gather light, combined with the brain’s insistence on processing this limited input instantaneously. But a camera’s sensor (or a rectangle of unexposed film) can accumulate all the light striking it for whatever duration we prescribe, thereby stretching its “instant” of perception indefinitely. Advantage camera.

For example, the camera’s narrow dynamic range is (exquisitely) mitigated in the barely perceptible light preceding sunrise and following sunset. Unlike night photography, when the light in the sky is so faint that extremely long exposures are required to register any foreground detail, and daylight/moonlight photography, when unidirectional light casts high contrast shadows that exceed a camera’s dynamic range, pre-sunrise/post-sunset twilight light is spread so evenly overhead that most shadows disappear.

About this image

Horizon-to-horizon skylight made dynamic range a non-factor in the above Alabama Hills pre-sunrise scene, while my camera’s instant-stretching ability revealed beauty present in a landscape that was nearly invisible to my eyes.

I arrived at this scene about 45 minutes before sunrise, but knew from experience I wasn’t too early to get to work. White with snow and towering 10,000 vertical feet above my location in the Alabama Hills, Mt. Whitney jutted in dramatic contrast to the dark sky. As my eyes adjusted to the limited light, the jumbled rocks of the Alabama Hills became vague, colorless shapes. Anyone relying on their eyes on this January morning would likely conclude that there’s not yet enough light for photography. But I knew better.

I started by juxtaposing a nearby fortress of boulders against Whitney’s serrated outline. While the mountains were the dominant feature to my eyes, I knew a long exposure would make the nearby rocks equally prominent, making their sharpness essential. Limited light made autofocus out of the question, so I stopped down to f16 to increase my margin for error and focused manually.

As expected, a thirty-second exposure at ISO 400 uncovered volumes of invisible detail and color my eyes missed. (It took two or three exposures to get the focus, exposure, and composition right, as I felt like I was working blind, and my meter was of little value in the darkness.) Though I was photographing in a fairly stiff (and frigid!) breeze at 4,500 feet, it was nothing like the hurricane wind that smeared the clouds above Whitney into an ethereal glaze. Another revelation of the long exposure was the sky’s exquisite, natural (not processing-enhanced) blue-hour hue.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A twilight gallery

Click and image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra, Mt. Whitney, Photography Tagged: Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra, Mt. Whitney, Photography

Alpenglow: Nature’s paintbrush

Posted on January 24, 2012

Red Dawn, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

168 mm

.8 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

The foreground for Mt. Whitney is the rugged Alabama Hills, a disorganized jumble of rounded granite boulders, familiar to many as the setting for hundreds of movies, TV shows, and commercials. These weathered rocks make wonderful subjects without the looming east face of the southern Sierra. What makes this scene particularly special is the fortuitous convergence of topography and light that rewards early risers with a skyline dipped in pink–add a few clouds and it’s a photography trifecta.

We’ve all seen the pink band above the horizon opposite the sun shortly before sunrise or after sunset. Sometimes called “the belt of Venus,” this glow happens because sunlight that skims the Earth’s surface just before sunrise (or shortly after sunset) has to battle its way through the thickest part of the atmosphere, which scatters the shorter wavelengths (those toward the blue end of the visible spectrum), leaving just the longer, red wavelengths capping the horizon. When mountains jut high enough to reach into this region of pink light, we get “alpenglow.” Towering above the terrain to the east, the precipitous Sierra crest, anchored by 14,500 foot Mt. Whitney (the highest point in the contiguous 48 states) and 13,000 foot Lone Pine Peak, is ideally located to receive this sunrise treatment.

The image above was captured on a frigid January morning. While the best light on the Sierra crest usually starts a couple of minutes before the “official” (flat horizon) sunrise, this morning Mt. Whitney hid behind the clouds until the alpenglow was well underway. Like a piece of art waiting for its spotlight, the cloudy shroud was pulled back just as the sunlight struck Mt. Whitney, and for a couple of minutes it appeared as if a giant paintbrush had dabbed the swirling canvas with pink.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A Mt. Whitney Gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Category: Alabama Hills, Mt. Whitney, Photography Tagged: Alabama Hills, alpenglow, Mt. Whitney, Photography

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About