Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Older Than History

Posted on October 17, 2023

Last Light on the Bristlecones, Schulman Grove, White Mountains (California)

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 100

f/16

1/4 seconds

Ask people to name California’s state tree and I’m afraid most would go strait to the palm tree—which isn’t even native to the Golden State. And though the correct answer is the redwood, those of us born and raised in California might argue that the stately oaks that dominate the foothills throughout most of the state conjure the strongest feelings of home.

But without diminishing the other trees, let me give our ancient bristlecone pines some much deserved love. Lacking the ubiquity of California’s palms and oaks, and the mind-boggling stature of our redwoods, bristlecones are largely unknown to California residents and visitors alike. But, not only do these twisting, gnarled trees look specifically designed for photography, for me it’s their fascinating natural history that truly sets bristlecones apart.

All varieties of bristlecone pines can live for millennia, but today I’m referring specifically to the Great Basin bristlecones, which have earned the distinction of being among the oldest living organisms on Earth. Earned being the operative word there.

Slow growth, a shallow and extensively branched root system, dense wood, and extreme drought tolerance contribute to the bristlecone pine’s longevity. How old are they? Well, many predate Christ, and at 4850 years old, the Methuselah tree (whose location somewhere near the Schulman Grove of the Inyo National Forest is a closely guarded secret) had already lived more than three centuries when the Egyptians broke ground on the first pyramid.

My favorite fact about these trees is that the more harsh a bristlecone pine’s environment, the longer it lives—a wonderful metaphor for perseverance that might bolster anyone battling the headwinds of life. Also found at the most extreme elevations of Nevada and Utah, Great Basin bristlecones especially thrive in the high elevation (low oxygen), extremely arid and rocky conditions above 9500 feet in the rain-shadowed White Mountains, just across the Owens Valley from the Sierra Nevada.

In the oldest bristlecones the majority of the wood is actually dead, with only a small area of living tissue connecting the roots to a few surviving branches. Having a relatively small amount of living tissue allows a bristlecone to sustain itself with minimal resources, while the extreme density of its dead wood serves as armor against harsh conditions. And once a bristlecone pine does die, with wood so hard and roots so robust, they can remain standing for centuries.

I visit these amazing trees each autumn in my Eastern Sierra Fall Color workshop. And though they’re technically not in the Eastern Sierra (but do provide spectacular views of it), and are completely devoid of fall color, so far no one has complained. On each visit I send my group up the Schulman Grove Discovery Trail loop, a short (one mile) hike starting at 10,000 feet with a 300 foot elevation gain that tests the fitness of all who attempt it. Compensation for all this effort is the opportunity to stroll among dozens of truly photogenic trees, each with its own unique character, that predate most human history.

All of the climbing happens in the first half mile—just about the time everyone is ready to turn around (or string-up the leader on the nearest bristlecone), the trail levels, then mercifully drops for the remainder of the hike. I’ve been doing this hike for more than 15 years, sometimes multiple times in a year, and if I’ve learned nothing else, I know to give everyone enough time to actually enjoy it.

It helps that most of the best trees are on the first half of the trail, as are 2 or 3 strategically placed benches. The ultimate payoff is a pair of striking bristlecones standing by themselves on a west-facing slope a little beyond the trail’s halfway point and just after the trail starts descending.

Because we start hiking about 90 minutes before sunset, and there’s no chance anyone will get lost, I let each person go at whatever pace makes them comfortable. And before setting everyone free, I remind them that there’s plenty of time to stop and take pictures (or pretend to take pictures) whenever they need to catch their breath.

I’ve visited these trees so many times, I rarely photograph them anymore—and when I do, few shots ever get processed. But as I got people started this year, I suspected things might be different because we’d been gifted with nice clouds—a welcome sight indeed.

I always let everyone in my group start up the trail before me, then wait at least 5 more minutes, so I can check on each person after they’ve had a a few minutes to experience the grade and thin air. In more than a few prior years I’ve had to race to the target trees, drop my gear, and double-back to check-on/assist others who might be struggling, but that wasn’t necessary this year—everyone made it to the trees by sunset without any trouble, albeit some much sooner than others.

When I first started coming here there were no posted requirements to stay on the trail, and photographers didn’t hesitate to clamor about the base of the trees in search of the best angle. But all this activity threatened to damage the trees’ shallow roots, so in recent years signs have been posted making it very clear not to leave the trail.

This new edict has actually made my job easier, as I no longer need to choreograph an assortment of photographers with conflicting agendas (even just one person scrambling up to the trees can ruin everyone else’s frames). Now we all just line up along the trail on either side of the trees, then shuffle positions when it’s time to change angles.

Clouds dominated when we arrived, but they moved swiftly, shuffling small patches of blue in the southern sky behind the trees. Though the clouds farther west were thick enough to completely block the sun, I was excited to see a small strip of blue just above the ridge that would ultimately swallow the sun for the day—if it held, we’d get nice late light, and maybe even some sunset color. Fingers crossed.

The trail almost completely loops around this pair of trees, providing more than 300 degrees of potential vantage points—some above, some below. My first frames this evening were at the far back of the loop, facing south and maybe 100 feet from the trees, allowing me to include the Sierra Crest and compress the distance between the trees and the peaks with a little bit of telephoto. As the clouds improved, I worked my way closer, shooting more beneath the trees to include more sky as well as well as a few patches of foreground snow.

So focused on the trees and sky, I forgot about the promising blue patch until the uphill treen suddenly lit up like it had been hit with a spotlight. Seeing the downhill had remained completely shaded except for its highest branches, I glanced westward and knew we’d only have a few minutes before the sun disappeared for good—fortunately I was in a perfect position to include the spotlit tree with the best clouds and could just stay put.

This turned into one of those situations where I simply worked as rapidly as I could without descending into actual panic-shooting. I started by checking my my histogram to ensure that I wasn’t clipping the essential highlights on the tree. With visual elements near and far, I had to be careful about depth of field, so I stopped down to f/16 and focused a little in front of the trees, and started shooting a range of compositions, horizontal and vertical, with a variety of sky and foreground (quickly refocusing each time I changed my focal length), firing continuously until the sun left—no more than five minutes.

The sunset color I’d hoped for never quite materialized, but no one complained. The evening’s combination of clouds and light, combined with the patches of snow, made this one of my favorite shoots at this most special of locations.

I will return next year

Trees Near and Far

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

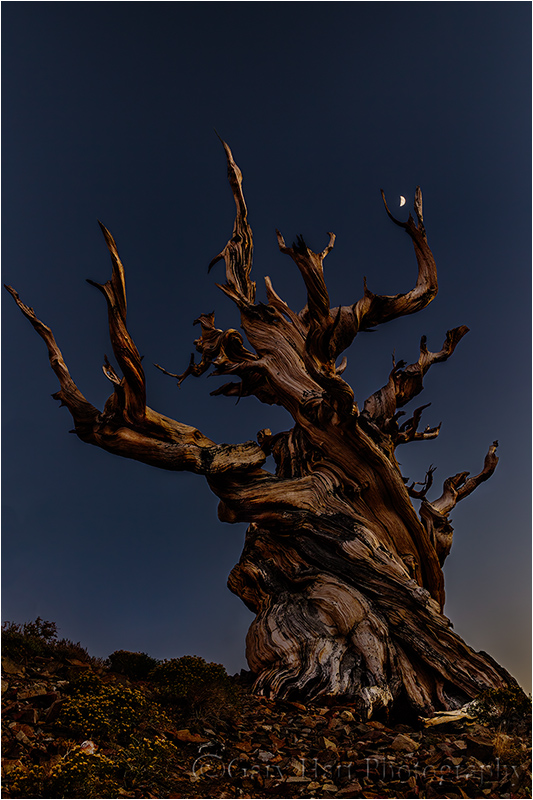

Waiting for the Stars

Posted on December 2, 2018

Nightfall, Schulman Grove, White Mountains, California

Sony a7R III

Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM

Breakthrough 6-stop ND filter

30 seconds

F/11

ISO 400

The bristlecone pines are among the oldest living organisms on earth. Some of these trees pre-date the Roman Empire by 2000 years—and they look every year of their age. The more harsh a bristlecone’s environment, the longer it lives.

As with the giant redwoods, it’s humbling to be among the bristlecone pines. What they lack in bulk they make up for in character, with their corkscrew branches, gnarled trunks, and intricate texture that make them fascinating subjects from any angle or distance, with any lens from wide to macro.

The plan this evening was to photograph these trees until sunset, then wait until dark and photograph them beneath the Milky Way. Despite an afternoon that included rain, fog, and lots of overcast, my hardy Eastern Sierra workshop group bundled up and toughed it out with the hope we’d get lucky. Occasionally patches of clear sky would tease us, only to vanish as quickly as it appeared.

Not getting what you came for is no reason to put the camera away, and I encouraged everyone to keep shooting while we waited. Because I was preparing everyone for a potential night shoot, I just found a composition I liked, set up my tripod in the fading light, and clicked a frame every couple of minutes.

When the darkness was nearly complete and there was still no sign of the Milky Way, we decided it head back down to the cars. I like to be the last one down the trail when we come out of the bristlecones in the dark, so I shot for a few more minutes while the rest of the group packed up. This image is my final frame of the evening. With no moon and a mostly cloudy sky, it was too dark to effectively compose and focus, so I stuck with the composition I’d started with when it was brighter. I used a 30-second exposure at f/11 and ISO 400 to capture more light than my eyes saw. That long exposure also really conveyed the motion in the clouds that had been whipping around overhead all evening. The rather ethereal quality I captured here is a perfect example of why twilight is an underrated time for photography.

Eastern Sierra Photo Workshops

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Few Bristlecones

Category: Bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM, Sony a7R III Tagged: bristlecone pines, nature photography

Plan B

Posted on October 30, 2014

I usually approach a scene with a plan, a preconceived idea of what I want to capture and how I want to do it. But some of my favorite images are “Plan B” shots that materialized when my original plan went awry due to weather, unexpected conditions (or my own stupidity).

In my recent Eastern Sierra workshop, the clouds I always hope for never materialized. Whenever this happens I try to use the clear skies for additional night photography, but I’ve always been a little reluctant to keep my groups out late in the bristlecones because: 1) it’s colder than many are prepared for (late September or early October and above 10,000 feet); 2) it’s an hour drive back to the hotel the night before a very early sunrise departure. But this year, after spelling out the negatives, I gave my group the option of staying out to shoot the bristlecones beneath the stars. My plan was to arrange for a car (or two) to take back those who didn’t want to stay, but it turned out everyone was all-in.

In most of my trips I know exactly where the moon will be and when, but for this trip I hadn’t done my usual plotting—I knew it would be a 40 percent crescent dropping toward the western horizon after sunset, but hadn’t really factored the moon into my plans. But as we waited for the stars to come out, I watched moon begin to stand out against the darkening twilight and saw an opportunity I hadn’t counted on.

Moving back as far as I could to maximize my focal length (so the moon would be as large as possible in my frame) required scrambling on a fairly steep slope of extremely loose, sharp rock (while a false step wouldn’t have sent me plummeting to my death, it would certainly have sent me plummeting to my extreme discomfort). Next I moved laterally to align the moon with the tree, and dropped as low as possible to ensure that the tree would stand out entirely against the sky (rather than blending into the distant mountains). Wanting sharpness from the foreground rocks all the way to the moon, I dialed my aperture to f/16 and focused on the tree (the absolute most important thing to be sharp).

With the dynamic range separating the daylight-bright moon and the tree’s deep shadows was almost too much for my camera to handle, I gave the scene enough light to just slightly overexpose the moon, making the shadows as bright possible. Once I got the raw file on my computer at home, in Lightroom/Photoshop I pulled back the highlights enough to restore detail in the moon, and bumped the shadows slightly to pull out a little more detail there.

As you can see, even at 40mm, the moon is a tiny white dot in a much larger scene. But I’ve always felt that the moon’s emotional tug gives it much more visual weight than its size would imply. Without the moon this would be an nice but ordinary bristlecone image—for me, adding the moon sweetens the result significantly.

A Plan B gallery (images that weren’t my original goal)

Click an image for a lager view, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, Moon Tagged: bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, moon, nature photography, Photography

If it’s Tuesday, this must be Bishop

Posted on September 30, 2014

Bristlecone Moonrise, Patriarch Grove, White Mountains, California

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

60 mm

.3 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

I have no one to blame but myself (a significant downside of being self-employed), and know I’m not going to get a lot of sympathy, but I just need to share how crazy my last few weeks have been. I’m in the final third of a stretch of three photo workshops in three time zones in three weeks, separated by a grand total of 20 hours at home.

Today I’m in Bishop, California, for day-two of my Eastern Sierra workshop that started yesterday in Lone Pine (California) and wraps up Friday morning in Lee Vining (California). This marathon travel schedule kicked-off on Thursday, September 12, when I left Sacramento for my Hawaii Big Island workshop. I finished that workshop with a Kilauea night shoot on Friday the 19th; Saturday morning I was back to the Hilo airport for my flight home (plane change and layover in Honolulu), finally dragging in the front door about 11 p.m. Saturday night.

At 8:00 a.m. Sunday morning my daughter deposited me back at the Sacramento airport for a flight to Salt Lake City, where I met Don Smith for the five-hour drive to Jackson Hole to help Don with his Grand Tetons workshop. Because the Hawaii/Wyoming weather conditions are so different, and my turnaround was so quick, I actually packed for the Teton before leaving for Hawaii (I’m so glad I did).

After a week in the Tetons, we wrapped up that workshop with a wet sunrise shoot on Saturday morning—then it was straight to the Jackson airport for a series of flights and airport shuttle that got me home Saturday night. I had just enough time to upload my images, refresh my suitcase, catch five hours sleep, and pack the car before heading back out the door early Sunday morning for the six-hour drive to Lone Pine for my Eastern Sierra workshop.

Am I tired? Probably, but I won’t feel it until my drive home on Friday. Am I complaining? Absolutely not. Not only did I do this to myself, how could anyone complain about three weeks filled with Hawaii, the Grand Tetons, and the Eastern Sierra?

And honestly, you can’t really be happy doing what I do without at least being able to tolerate travel. This year, before my current marathon travel stretch, I’ve been to Death Valley, Yosemite (many times), Maui, Kauai, the Grand Canyon three times (including a raft trip), plus Page and Sedona. And truth be told, I enjoy driving, and don’t mind flying. Driving relaxes me, and flying is an opportunity to catch up on my reading and writing. Nevertheless, it will be nice to have consecutive days home, in my own bed,with the alarm off—before next month’s trip to the Columbia River Gorge….

A little more about the Eastern Sierra and this image

Everyone knows about Hawaii, and most know about the Grand Tetons, but mention of the Eastern Sierra still elicits a blank stare from many people. That’s probably because most tourists haven’t discovered it yet (the photographers certainly have). With Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills (if you’ve ever seen a John Wayne, Gary Cooper, or John Ford western, you know the Alabama Hills), the bristlecone pines (in the White Mountains, across the Owens Valley from the Eastern Sierra), Mono Lake, Yosemite’s Tuolumne Meadows, and lots of fall color, it’s my most diverse photo workshop.

We started yesterday evening with a nice shoot of the Whitney Portal waterfall, in the shadow of Mt. Whitney. This morning we photographed alpenglow on Mt. Whitney and the Sierra crest from Whitney Arch (aka, Mobius Arch) in the Alabama Hills. After breakfast we made the easy, scenic one hour drive to Bishop, which is where I am now (thank you, Starbucks). Tonight it’ll be the bristlecone pines, at more than 4,000 years, among the oldest living things on Earth (older even than Larry King!).

For tonight’s bristlecone shoot I’ll take the workshop to the relatively accessible Schulman Grove. But when I’m on my own, I often continue thirteen unpaved miles to the Patriarch Grove. And that’s the trip I made a few years ago, because I thought the bristlecones would make a nice foreground for the rising full moon, and because the Patriarch Grove has a clearer view of the eastern horizon than the Schulman Grove.

At the Patriarch Grove, finding the clear view I wanted required me to take off cross-country. Unfortunately, when I scaled the final ridge, I found the horizon obscured by clouds. Not to worry, the light was perfect for photographing these weather-worn, gnarled trees. I’m usually pretty good about catching the moon’s appearance, but because I’d written it off for this evening (shame on me), I failed to register that the clouds were breaking up. Which is why I was both surprised and pleased to find the moon’s glowing disk hovering just above the clouds a few minutes after sunset.

I’d been wandering so much, and so focused on the nearby scene, that I hadn’t identified a particular tree for any potential moon shot (also shame on me). With very little time before the foreground/moon contrast became un-photographable, I felt quite fortunate to find this tree so quickly. A wide composition would have shrunk the moon to nearly invisible, so I stepped back as far as the terrain allowed so I could zoom closer and compress the separation (and enlarge the moon a little). With a vertical composition, I had to decide on rocks or sky, but it wasn’t hard to decide that foreground rocks were far more interesting than empty sky.

Let’s see, what’s tomorrow? Wednesday. Lee Vining, here I come….

An Eastern Sierra gallery

Click an image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, full moon, Moon Tagged: bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, nature photography, Photography

Beneath the stars

Posted on October 1, 2012

Bristlecone Star Trails, Schulman Grove, White Mountains, California

Canon 1Ds Mark II

36mm

22 minutes

F/4

ISO 200

October 2012

I lead photo workshops in lots of beautiful, exotic places, but I particularly look forward to the Eastern Sierra workshop for the variety we get to photograph. Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, Mono Lake and Yosemite’s Tuolumne Meadows, lots of fall color in the mountains west of Bishop and Lone Pine, and the ancient bristlecones in the White Mountains, east of Bishop.

It’s the opportunities to photograph the mountains surrounding Bishop that most stimulate my creative juices. Each fall the small lakes, sparkling streams, and steep canyons west of Bishop are lined with aspen decked out in their vivid autumn yellow. Contrast that with the arid White Mountains east of Bishop, where virtually nothing thrives except the amazing bristlecone pines. The bristlecones are among the oldest living things on Earth, and they look it. The character they’ve earned by enduring up to 5,000 years of cold, wind, thin air, and water deprivation makes them ideal photographic subjects. There’s wonderful texture in the bristlecone’s twisting trunk and branches, but sometimes I like to turn off the texture with a silhouette that emphasizes the gnarled shape.

The bristlecone here clung to a steep hillside in the Schulman Grove of the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest. I was there with three friends on a moonless, late September night in 2007. They wanted to light-paint the tree, but I wanted something that just emphasized the tree’s shape against the stars. With our shots set up, I delayed my exposure for a few seconds while they hit the tree with a bright flashlight, clicking as soon the world went dark. Then we just sat and waited in the chilly air, enjoying the sky, laughing quite a bit, but sometimes just appreciating a silence that’s impossible to duplicate anywhere in our “normal” (flatland) lives.

As we waited we scanned the sky, thick with stars, for a rogue airplane that might threaten to soil our frames. Only one appeared, and when it did I held my hat in front of my lens, holding it there for about fifteen seconds, until the plane moved on. (If you look closely you can actually see a small gap in the same place on the otherwise continuous star trails.)

We had long exposure noise reduction turned on, so we couldn’t see our results until our cameras finished their processing. The pictures didn’t pop up on to our LCDs until we were halfway back to Bishop, but I was driving and had to wait until we got back to town. We pulled into Bishop, tired and hungry, so late that we had a hard time finding anything open, but everyone was so pleased with their images that even Denny’s tasted good.

An Eastern Sierra Gallery

(Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show)

Category: Bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, Photography Tagged: bristlecone pines, Photography, star trails, stars

From one extreme to another

Posted on August 1, 2012

* * * *

In my previous post I wrote about California’s extremes. I used Badwater in Death Valley to illustrate, but of course there are many more examples. Case in point: the bristlecone pines of the White Mountains, just east of Bishop, across the Owens Valley from the Sierra Nevada.

The more heralded, heavily traveled Sierra gets most of the rain and snow from the Pacific, rendering the White Mountains a high elevation desert. With very little water to sustain foliage, fierce winds scour the White’s rocky surface unchecked. Water (and foliage) also moderates temperatures (lower highs, higher lows)–without water’s moderating effect, high temperatures in the White Mountains are higher and low temperatures are lower than corresponding elevations in the nearby Sierra.

Enter the bristlecone pine, a hardy conifer that has evolved to not only survive in these extremes, it thrives. Thrives to the point that it is generally acknowledged as the oldest living thing on earth (older, even, than Larry King). Some bristlecones approach 5,000 years old; the tree in this image is around 4,000 years old, give or take a millennium (due to, believe it or not, concerns about vandalism, individual bristlecone ages aren’t revealed).

The Schulman Grove Discovery Trail is a one mile loop with great access to some magnificent trees. It’s a very well-marked, heavily used trail, but it’s quite steep. And at over 10,000 feet elevation, it will definitely test your lung capacity. At just about the halfway point of the trail, you’ll find a magnificent bristlecone pair, well worth the effort to get out there. The trail here loops around these trees, providing 270 degrees of perspective.

The most popular view here, the view that seems to attract the most photographers, is close and looking up at the trees against the sky. But this evening I liked that the (often obscurred by haze) Sierra crest was clearly visible, and saw that the sky had potential for color, so I picked a more distant vantage point up the trail a bit. From there I could isolate the tree against the mountains and compress the distance somewhat with a moderate telephoto.

Using some scruffy yellow shrubs to anchor my foreground, I decided a vertical composition allowed me to compose the tree a little tighter. It was about 75 feet away, which meant at f16 and 75mm, focusing just a little in front of the tree gave me sharpness from 25 feet to infinity (as reported by the hyperfocal app in my iPhone). The color came late, after many photographers had packed up and headed back to the visitor center. While the sunset didn’t paint the entire sky, it very conveniently peaked in direct line with my composition. I love it when everything comes together.

<< Read more about my approach to focusing >>

Category: Bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra Tagged: bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, Photography, sunset

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About