Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Happy Anniversaries to Me

Posted on January 26, 2026

Rural Lightning Strike, Southeastern Wyoming

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 G

.6 seconds

F/8

ISO 800

I just realized that January 2026 marks a couple of milestones for me. Twenty years ago this month, I left my “real” job at Intel (good company, lousy manager) to pursue my dream of becoming a landscape photographer. And 15 years ago this month, I started writing this blog.

Leaving Intel was a leap of faith that, I now know, was far riskier than I believed at the time. That it worked out I attribute more to fortuitous timing than some kind of genius master plan. By the time I left Intel, I’d accumulated a pretty good portfolio of images that I’d printed and sold in weekend art shows. I also had prints in a few local galleries, but print sales alone didn’t generate anywhere near enough money to justify leaving a good job (or for that matter, even leaving a bad job).

My first post-Intel step was to ramp up my art show schedule and upgrade my art show booth lighting and display panels; despite decent art show success ($1000-$4000/weekend, doing the math told me that the time, effort, and relentless (intrastate) travel necessary to earn a fulltime income on the art show circuit would soon suck the joy from photography, and leave precious little time for actual photography. So I concentrated on a handful of quality shows within a 100 mile radius of my Sacramento home, and started looking for other ways to support myself with landscape photography.

I knew that many landscape photographers made a good living selling stock images, but by 2006 it was clear to me that digital photography was taking a toll on stock photography income, and there no end to the decline in sight. A couple of years earlier, just a few months after purchasing my first DSLR (a Canon 10D), I’d taken a weekend photography workshop to explore Point Reyes (thanks, Brenda Tharp!) and it occurred to me that I was qualified for something like that in Yosemite: I know photography well enough to teach it, I have a lifetime of Yosemite knowledge, my 20 years in the tech world had focused almost entirely on technical communications (training, writing, tech support), and (not insignificant) I like people. That this insight happened a few years before the photo workshop wave flooded the photography world was a fortunate fluke.

Pivoting to the photo workshop plan, I did a little teaching and guiding as 2006 progressed, but most of that first year was spent setting my workshop business up: building a website, scheduling workshops for the best times to photograph Yosemite, and getting the word out. I also stuck with my modest weekend art show schedule, doing one every two or three months.

Looking back now, I realize the I never would have succeeded had I not spent money I didn’t really have to hire a professional web designer to create a professional website (this was before website templates made web design easy for the masses), and display a monthly ad in “Outdoor Photographer” magazine. By the time my full workshop schedule kicked off in early 2007, every 2007 workshop had filled, and subsequent workshops started filling almost as soon as I posted them.

That first year was all Yosemite, but I soon expanded to include the Eastern Sierra and Death Valley, then Hawaii, Grand Canyon, and beyond. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my friend Don Smith, who’d already had a very successful career as a professional sports photographer, but was hoping to transition to landscape photography. Don assisted virtually all of my early workshops, and within a year or two was doing his own workshops too, which I in turn assisted. (Over the years our workshop schedules became so packed that we’re no longer able to assist each other much, but Don and I still partner on the New Zealand and Iceland workshops, and stay in pretty close contact throughout the year.)

Between arranging lodging, applying for location permits (not to mention meeting all the criteria each permit requires), answering e-mails from workshop students and potential workshop students, preparing workshop material, and actually conducting the workshops, my plate became pretty full. As much as I enjoyed doing the art shows (I really did), I felt like I was running two businesses. When the Great Recession took and obvious bite from my art show sales, while my workshops attendance didn’t even flinch, dropping the art shows became a no-brainer.

To further increase my exposure, I started writing a blog on a small photoblog site in early 2009. I say this was to increase my exposure, but it was just as much in satisfy my insatiable urge to write. I’ve been a writer all the way back to first grade, when each Monday we were assigned a list of spelling words to learn before the Friday spelling test (am I dating myself, or do they still do that?). The week’s homework assignment was to a create a “spelling sentence” for each word. But instead of spelling sentences, I always wrote spelling stories that used all of that week’s words. I can’t explain why I gave myself that extra assignment for no tangible benefit, except that I thought it was fun.

Ever since, I’ve always had to be writing something. For many years it was short stories (plus a novel that has lived in my head, but so far hasn’t made it to the page). At Intel I was a tech writer, which helped me refine my technical communication skills while feeding my internal writing monster. (One reason I left was resistance from “above” to my attempts to make inherently dull writing more readable.)

While I enjoyed the small community of photographers on that original photoblog site, I quickly found its interface limiting, and soon realized my page wasn’t attracting the eyeballs I’d hoped for. So I started looking for a blogging site that addressed those concerns, and in January 2011 landed on WordPress. What started as a weekly (-ish) blog of a few hundred words, grew to include posts with word counts in the thousands, photo galleries, and a Photo Tips section. By my estimation, I’ve probably written close to two-million words—and counting….

As much I’d love to attribute that volume to my own herculean work ethic, I don’t think I, or anyone for that matter, could sustain a weekly blog, week-in and week-out, for 15 years on guts and willpower alone. This anniversary says less about my dedication and discipline than it does about the fact that I simply love to write.

According to WordPress, I have nearly 40,000 subscribers. But because this blog is as much (more?) for me as it is for my readers, I’ve never tried to monetize those numbers by displaying ads or intrusive affiliate links. It’s satisfying to know that it has led to many workshop signups—probably not enough to justify all the time I spend on it, but that’s okay. And I never tire of hearing that people actually read and benefit from what I’ve written.

Though it wasn’t my conscious intent at the beginning, this blog has become an integral part of my photography. That’s because the subjects I choose, and the way I choose to capture them, are very much a reflection of my relationship with the natural world. To me, much of the beauty in my subjects transcends the visual and resides in the underlying natural laws. Augmenting my images with descriptions and explanations of those natural processes, makes my subjects even more beautiful to me, and (I hope) through my words, to my readers.

For example, lightning. I will freely admit that lightning’s appeal might be much greater to a life-long Californian like me, than it is to, say, a Floridian, to whom lightning is at best a nuisance, and at worst a persistent source of danger. But I do love everything about lightning—not just the way it looks, but the processes that cause it. Along with enabling me to share my images of lightning, my blog gives me an excuse to learn more about lightning, and to share that knowledge. Whether it’s the fascinating science that causes lightning, how to read the sky to understand where lightning might strike next, staying safe when lightning threatens, or the even best way to capture lightning with a camera, I’ve learned so much and am grateful to have a platform for sharing it.

Even though I’ve photographed lightning at Grand Canyon every year since 2012, it took last June’s Midwest storm chasing trip to show me how much I don’t know. At Grand Canyon, we’re usually photographing distant thunderstorms across the canyon. But not only does storm chasing put you in much closer proximity to the electrical storms generating the lightning, these storms, whether rotating supercells or “merely” towering thunderheads, are on a totally different scale.

These insights came on the trip’s very first afternoon, when we hightailed it from our Denver hotel up through the plains of northeastern Colorado and into southeastern Wyoming. The image I share today I captured on the workshop’s second stop. It was my introduction to both the power and proximity of Midwest electrical storms, and with it the realization that unlike Grand Canyon storm chasing, where we generally set up a safe distance and then just wait for the lightning, Midwest storm chasing is actual get-in-the-van!-step-on-it-screech-grab-your-gear-sprint-shoot-retreat!-step-on-it-repeat STORM chasing.

Later this afternoon I got my first look at an actual supercell. And a few days after that, my first (and second, and third, and fourth, and…) tornado. A couple of days later we witnessed a supercell and lightning display that was one of the most breathtaking experiences of my life. And nearly every day of this nearly 2 week trip we saw lightning.

Calling this storm chasing experience life-changing might sound hyperbolic, and maybe even a little cliché, but I can think of few things in my photography life that have left me more awestruck. It certainly rivals other photography firsts, like rafting Grand Canyon, and viewing the northern lights and a total solar eclipse. To think that I’ve been able to earn my living witnessing these sights, and to share it all here, Is a blessing I never want to take for granted.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Storm Chasing Memories

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: lightning, Lightning Trigger, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V, storm chasing Tagged: lightning, nature, nature photography, Photography, storm chasing, thunderstorm

Grand Canyon Lightning 2024: Part 2

Posted on August 16, 2024

When I returned from my Grand Canyon Monsoon photo workshop earlier this month, I was so excited about this year’s last-day lightning experience that I immediately processed a few images and sat down to blog about them. But when my blog started approaching 4000 words, I thought for everyone’s sanity (both yours and mine), it might not be a bad idea to split my ramblings into two blogs. In the first one I detailed, among other things, the story of the actual shoot that produced nearly 60 lightning images on the day the workshop ended. I also wrote about the Southwest monsoon in general, and the genesis of my lightning chasing obsession.

Now I’ll move on to some of the science of lightning, and my thoughts on including lightning in an image. Without further adieu…

Here’s Part 2

When you’ve been writing a weekly photo blog for over 13 years, at some point you’re bound to run out of new things to say. When that happens, the goal becomes finding fresh ways to express potentially stale thoughts. So forgive me if you’ve heard this before, but it bears repeating: Landscape photography captures the relationship between Nature’s enduring and ephemeral elements.

In the simplest terms possible, Nature’s enduring elements are those landscape features we travel to view and photograph, confident in the knowledge that they’ll be waiting for us when we arrive: mountains, lakes, rocks, trees, waterfalls, and so on. On the other hand, Nature’s ephemeral phenomena include the always changing light and weather, celestial events, and seasonal variations that play in, on, and above the landscape—never-guaranteed phenomena we might hope (and plan) to find when we arrive at our enduring destinations, but also those conditions that simply surprise (or disappoint) us. Regardless of how they converge, the landscape photographer’s job is to combine the best of Nature’s enduring and ephemeral elements in the most compelling way possible.

Pretty straightforward, right? For some things perhaps, but maybe not so much for others. I’d put lightning in the not-so-much category: for starters, we never know where it will strike next, or if it will even strike at all. And even when it does happen, lightning comes and goes faster than our shutter fingers can respond. But, like most of Nature’s most fickle ephemeral phenomena (alliteration anyone?), the more I understand lightning, the better my success.

Where my lightning pursuit is concerned, it doesn’t hurt that I’ve always been something of a weather nerd, starting in my early teens with an inexplicable fascination with the weather forecast segment of KGO-TV’s (Channel 7 in San Francisco) nightly news (thank you, Pete Giddings), continuing with meteorology classes in college, as well as my ongoing consumption of weather articles, books, blogs, and podcasts.

Despite this general interest in meteorology, I never really took the time to study lightning closely until I started trying to photograph it. I knew the basics, but the deeper I looked, the more fascinated I became. And not coincidentally, the more lightning success I had.

For starters, a lightning bolt is an atmospheric manifestation of the truism that opposites attract. When two oppositely charged objects come in close proximity, an equalizing spark is produced. For example, when you get shocked touching a doorknob, on a very small scale, you’ve been struck by lightning.

On the atmospheric scale, understanding the mechanism isn’t too difficult to get your mind around if you remember a few basic facts:

- Warm air rises because it’s less dense than cold air. And cold air falls because it’s more dense.

- This warm air rising, cold air falling thing is the underlying engine of convection: air that’s warmer than its surroundings rises, until it cools enough be colder than its surroundings.

- Since warm air holds more moisture (water vapor) than cold air, anything that makes air cooler (like rising through the atmosphere) squeezes its moisture out, which causes its contained water vapor to condense and form clouds.

- The greater the temperature difference between the warmer lower layers of the atmosphere, and colder higher layers, the more unstable the atmosphere is said to be. This instability drives the convection process that leads to thunderstorms.

- Warm air will continue rising until it is no longer warmer than the surrounding air, potentially ascending high enough for the water vapor it carries to condense and freeze. Or until it encounters an inversion.

- An inversion is a cap (layer) of warmer air sitting atop cooler air, an aberration that puts the brakes on the rising warm air.

Of course weather phenomena are rarely simple, but in general the ingredients for lightning are moist air (high humidity), an unstable airmass atmosphere uncapped by inversion, and surface heating to initiate the convection process. With these ingredients in place, adjacent columns of ascending and descending air generate collisions between the contained water molecules.

When ascending and descending water molecules collide, negatively charged electrons stripped by the collision attach to descending molecules, giving them a net negative charge; the remaining molecules, now with a missing electron and a net positive charge, are lighter and continue upward. This electron imbalance is called ionization. The result is a polarized cloud that’s positive on top and negative at the bottom. The most powerful convective updrafts carry water droplets high enough that they freeze, shifting the ionization process into overdrive with ice particle collisions.

Since nature really, really wants to correct a charge imbalance, and always takes the easiest path, if the easiest path to electrical equilibrium is between the cloud top and cloud bottom, we get intra-cloud lightning; if it’s between two different clouds, we get inter-cloud lightning. And when the net charge beneath the cloud is positive while the cloud bottom is negative, we get cloud-to-ground lightning. (This describes negative lightning; positive lightning, where the cloud/ground charges are reversed, is also possible, but less common.)

In addition to the vertical motion within a thunderstorm, there is also horizontal motion that moves a cell across the landscape. This movement feels a little more random because it’s driven by invisible winds in the middle levels of the atmosphere. But keeping an eye on a storm can at least enable a general understanding of the direction it’s moving—important information when you want to photograph lightning (also when you want to stay alive).

With lightning comes thunder, the sound of air expanding explosively when heated by a 50,000-degree jolt of electricity. While lightning’s flash zips to our retinas at more than 186,000 miles per second, thunder lumbers along at the speed of sound, a pedestrian 750 miles per hour—nearly a million times slower than light.

Knowing that the thunder occurs at the same instant as the lightning flash, and the speed at which both travel, we can calculate the approximate distance of the lightning strike. While we see the lightning pretty much instantaneously, thunder takes about 5 seconds to cover a mile. So dividing by 5 the number of seconds between the instant of the lightning’s flash and the arrival of the thunder’s crash gives you the lightning’s approximate distance in miles (divide by 3 for kilometers).

Technically, if you’re close enough to hear the thunder, you’re close enough (probably within 10 miles) to be struck by the next lightning bolt. But watching lightning at Grand Canyon over the last dozen years, I’ve become pretty comfortable reading the conditions and determining when the storm’s too close. I still err on the side of safety, shutting down a shoot sooner than many in the group might like, but I haven’t lost anyone yet, so I must be doing something right. (And seriously, I know people understand when I terminate a shoot because lightning is too close, and it frustrates me just as much as it does them.)

Understanding thunderstorms in general, and lightning creation in particular, has helped me more accurately determine where to point my camera for the best chance of success. Given the number of Grand Canyon vistas with views extending dozens of miles up, down, and across the canyon, at the beginning I’d just point my camera and Lightning Trigger in the direction of any cloud that was producing rain. But now I know that all rainclouds aren’t created equal, and that the clouds most likely to produce lightning are the darkest and tallest. The darker a cloud, the more moisture it contains, and the greater the potential for ionizing collisions. The taller a cloud, the more likely it is to contain the ice that supercharges the ionization process.

And since lightning often precedes thunderstorm’s motion, striking the rim (or inside the canyon) in front of the falling rain I’d previously targeted my compositions on, I’ve become better able to anticipate where the next bolt might strike and adjust my composition proactively.

On the day I captured this (and nearly 60 other) lightning images, with ample monsoon moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and an uncapped atmosphere, all that was needed was warming sunlight to kick off the convection process that sends the moisture skyward. The morning started cloudless, and from my vantage point at Grand Canyon Lodge (right on the North Rim), by midmorning I could see billowing clouds far to the south. Even though the workshop had ended that morning, about half the group had stayed, so I summoned them with a text message.

We started seeing lightning less than an hour later. During the three or so hours of activity, it was fun watching various cells bloom, mature, and peter out. During most of that period of activity there was overlap, as one cell was diminishing, another was starting up—sometimes in the same general direction, other times over a completely different part of the canyon. The overall trend of the storms’ motion was east-to-west, across the canyon, along the South Rim.

I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating that I think the absolute best way to really appreciate lightning is to spend time closely scrutinizing a still image. With a lifespan measured in milliseconds, a lightning bolt is the epitome of ephemeral—whether in person or in a video, it’s a memory before we fully register that lightning just fired. We have a general idea of its location and overall shape, but it’s not until we’re presented with a frozen instant of that lightning bolt’s peak energy that we fully understand the details of what took place.

It doesn’t take long to realize that each strike has its own personality, distinctly different from all others. Examining my images later, I always look to process the lightning images with the most personality. One bolt’s most striking (pun unavoidable) feature might be the circuitous route it followed to get from cloud to ground, or the network of related simultaneous bolts associated with it, or the numerous spiderweb filaments it produced, or maybe the sheer power and brilliance it displayed.

Thinking in terms of matching these ephemeral features with the enduring canyon, on a macro scale the enduring aspect was determined when I decided to visit Grand Canyon during monsoon season. But my decisions for how to combine the landscape ephemeral lightning have evolved, influenced now by the knowledge I’ve gained, and also by shifting priorities. With so many in my images lightning portfolio, my goal is no longer to capture lightning no matter what (by simply pointing in the direction most likely to get lightning, regardless of the scene there)—now I can now afford to factor the better composition into my framing decisions. While that shift might reduce the number of strikes I capture, it increases the chance of getting strikes I especially like.

Above is a series of four strikes from the afternoon’s most active cell, captured over a 12 minute span. Despite similar origin and landing locations, you can see that each bolt is unique. I remember them in a very general sense because each induced from the group reflexive, giddy exclamations that far surpassed the standard “Ooooh!” every lightning bolt elicits. Despite retaining a vague memory of their shapes and paths, I love that I was able to freeze each one for detailed examination.

JOIN ME FOR NEXT YEAR’S GRAND CANYON LIGHTNING CHASE

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Lots More Lightning

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Grand Canyon, lightning, North Rim, Photography, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V Tagged: Grand Canyon, lightning, Monsoon, nature photography, North Rim, thunderstorm

Grand Canyon Lightning 2024: Part 1

Posted on August 11, 2024

Back at it—the chase is on

Every year I schedule one or two (and one time three) photo workshops for the peak weeks of the Southwest US monsoon. Despite the summer crowds (which I’ve become pretty good at avoiding), I’d argue that monsoon season is the best time to photograph Grand Canyon. Given the monsoon’s frequent mix of thunderstorms and sunlight, adding colorful sunrises/sunsets and rainbows to Grand Canyon’s splendor are always a real possibility. And photographing the Milky Way above Grand Canyon is a true highlight for everyone. But despite these undeniable visual treats, more than anything else, foremost in almost everyone’s mind is lightning.

Each time I start with a new workshop group (that is clearly brimming with lightning aspirations), I’m reminded of the first time I tried chasing lightning—both the extreme disappointment of failure, and (especially) the ultimate euphoria of success. So even with hundreds (thousands?) of lightning images to my name, reviving these memories help me live vicariously through the joy and disappointment of my workshop students.

Though (or maybe because) I’ve never lived anywhere that got much lightning, I’ve been fascinated by lightning since I was a child. (Lightning is so rare here, when Californians hear thunder, instead of sheltering safely like sane people, we run outside so we don’t miss anything.) So I guess it makes sense that ever since I picked up a camera, I’ve dreamed of photographing lightning.

In the beginning…

In 2012, Don Smith and I drove to Grand Canyon to try and make that happen. I mean, how hard could it be? Armed with our cameras and virgin Lightning Triggers, on that first trip we endured enough frustration—lots of lightning that for a variety of rookie reasons, we couldn’t seem to capture—our initial dreams of dozens of lightning images became prayers for just one.

Those prayers were answered many times over toward the end of the visit, when a surge in monsoon thunderstorms on and near the South Rim coincided with just enough of a bump in experience (and humility) to equal success. On our last day, so thrilled were we by our South Rim lightning experience, that instead of heading straight home as planned, we detoured four hours in the opposite direction to the North Rim. There, in just a few hours, we captured even more new lightning, more than enough to energize our long drive back to California. I was hooked.

After those beginner’s ups and downs, my lightning success has increased each year. Of course when no lightning happens, there isn’t much I can do about it, but learning to interpret the forecasts (including the fairly technical NWS forecast discussions), understanding the patterns of monsoon storm development and behavior in and around Grand Canyon, increased familiarity with my Lightning Trigger, and (finally) finding an app that reliably alerts me about lightning far outside my range of vision, has significantly increased my lightning success rate.

Lightning Trigger love

For daytime lightning, I can’t overstate the importance of a reliable lightning sensor with range. First, don’t even think about trying to photograph lightning in daylight without a device that detects the lightning and triggers your camera. I know people try the see-and-react technique, but success with this approach is mostly luck—if you do get a bolt, it was almost certainly not the one that made you press the shutter, it was a secondary or tertiary (or later) bolt that followed the initial one. And one of the most common mistakes I see aspiring daylight lightning shooters make is adding an extreme neutral density filter to achieve the long exposures that yield so much success at night. But night lightning shows up because of the extreme contrast between the brilliant lightning against black surroundings; that contrast disappears in daylight, so you end up with a many-second/minute exposure with lightning bolts that last a minuscule fraction of a second, rendering the lightning faint or (more likely) invisible.

Fortunately, the lightning sensor Don and I started with has turned out to be the best, saving us lots of frustration, research, and money. You’ll find many lightning sensor options, most of which I’ve encountered in a workshop, but the only one that I’ve seen work reliably is the Lightning Trigger (though people use the name as a generic, this is the only one that can use it legally). There are fancier sensors, and cheaper sensors, but I’ve found none that combine reliability and range as well as the Lightning Trigger. (I’m not saying that the others don’t work, I’m saying that I’ve never seen any that work as well as the Lightning Trigger, so even though I get no kickback or other benefit from pushing it, the Lightning Trigger is the only lightning sensor I recommend.)

Playing the odds

On a textbook monsoon day, the storms start firing south of the canyon (around Flagstaff and Williams) mid-/late-morning, and move northward as the sun ascends, usually arriving at the canyon late morning or early afternoon. While waiting for the storms to arrive, I rely on my Lightning Tracker Pro app to monitor the approaching activity and get ahead of it, especially when I’m on the South Rim, where my groups stay about 10 minutes from the rim. (It’s easier on the North Rim because our cabins are right at the rim.)

Chasing lightning means obsessive monitoring of weather forecasts. And counterintuitively, my workshop groups have the most success not when the forecast calls for lots of thunderstorms, but when the thunderstorm odds are in the 20 to 40 percent range. That’s because Grand Canyon has a multitude of the vistas with broad, distant views up, down, and across the canyon. These views, combined with the Lightning Trigger’s incredible range (I’ve used mine to capture daylight lightning more than 50 miles away), enables us to safely photograph distant storms—storms usually so far away that we don’t hear the thunder.

So a 20 percent chance of thunderstorms means that (very roughly) 20 percent of the forecast area will get lightning, so it’s usually not difficult to stand on the rim and find lightning happening somewhere within the Lightning Trigger’s range. On the other hand, when the forecast calls for a 50 percent or higher chance of thunderstorms, we do indeed get much more rain and lightning, but usually there’s too much to photograph safely because you never want to be photographing the storm you’re in.

Let’s go fishing

As thrilling as chasing lightning might sound, it’s really about 95 percent arms folded, toe-tapping, just-plain-standing-around-scanning-the-horizon, suddenly interrupted by random bursts of pandemonium. Often, (and despite years of experience) after all that anticipation-infused waiting, the response to the first lightning bolt is either: 1) Crap, the lightning is way over there; or 2) CRAP! The lightning is right here! What ensues is a Keystone Cops frenzy of camera bag flinging, tire screeching, gear tossing, tripod expanding, camera cursing, Lightning Trigger fumbling bedlam. Followed by more waiting. And waiting. And waiting….

I’ve always found the waiting part of lightning photography a lot like fishing—spiced up by the understanding that these fish have the ability to strike you dead without warning. Both fishing and lightning chasing are an intoxicating mix of serene communing with nature, with an undercurrent of giddy anticipation. And whether you’re fishing or trying to photograph lightning, a strike is far from a guarantee that you’ll reel anything in.

Just as fish somehow slip the hook, seeing a lightning bolt is no guarantee that my camera recorded it. Some of my lightning “the one that got away” stories, especially when I was just starting, turned out to be something I did wrong (and my list of stupid mistakes is too long, and embarrassing, to detail in public), but usually it’s simply because lightning can sometimes come and go before even the fastest camera can respond.

One frustration that I’ve learned to deal with is that when a Lightning Trigger is attached and turned on, the camera is in its shutter half-pressed mode (to allow the absolute fastest response), which disables many/most (varies with the camera) controls and the LCD image review—and I guarantee that the surest way to ensure another lightning strike is to turn off your Lightning Trigger to review the last frame, because the instant you do, a spectacular triple-strike will fire right in the middle of your frame. Guaranteed. (This is an extension of the axiom every photographer knows: The best way to make something you’ve been waiting for happen, is to put away your camera gear.) And though there’s no way to prove it, I think we all know that each time we pull the line out of the water to make sure the worm is still there, the “big one” swims right by.

Better late than never

This year I only did one Grand Canyon Monsoon workshop, and true to form, nearly got carpal tunnel scrolling through the weather forecasts in the weeks leading up to the trip. One week in advance, the conditions looked promising, but as the workshop approached, I was alarmed to see it trending drier with each forecast. By the time we started, the NWS was promising clear skies from start to finish.

I’ve seen forecasts like this before, and while they often do come true, I’ve also seen them change on a dime. I also found hope in the forecasts for Flagstaff and Williams to the south (that’s right, I don’t just obsessively scroll the Grand Canyon forecasts, but the nearby forecasts as well), which had thunderstorm chances in the 20-30 percent range all week. This told me that the moisture was nearby, and only a very slight change would send it the 70 or so miles north to Grand Canyon.

The evening of the workshop’s first day (Monday), a few clouds were added to the Thursday forecast—no rain, but at least the moisture was moving in the right direction. Then, in the forecast released Tuesday evening, we were “promised” a 20 percent chance of rain on Friday. With each subsequent forecast (they’re updated several times a day), it appeared things were trending in the right direction for the end of the week and beyond. Unfortunately, the workshop ended Friday morning. So I encouraged everyone with flexibility in their schedule to extend their stay at least through Friday afternoon, and about half the group was able to do it—including Curt (the photographer assisting me) and me.

This workshop enjoyed beautiful sunrises and sunsets, including a real jaw-dropper at Cape Royal on Thursday evening, plus a pretty great Milky Way shoot the night before. And a few in the group stayed up late on Thursday night and got some nice, though fairly distant, night lightning from the Grand Canyon Lodge deck. But those of us who opted to stay an extra day hung our lightning hopes on the Friday and Saturday forecasts.

Much to the consternation of those who added a night hoping for lightning, Friday morning dawned cloudless. But I reassured everyone that this is actually a good thing (it really is), because clear skies maximize the surface heating that fuels the convection thunderstorms require. Though the workshop officially ended after that morning’s sunrise shoot, I promised them I’d be around and happy to help. For starters, I created a text thread that enabled me keep them up to date on the thunderstorm development.

Then I camped out in the Grand Canyon Lodge Sun Room, keeping one (or more) eye on the spectacular view across the canyon to the South Rim and beyond. Late morning my lightning app started reporting strikes north of Williams, less than 60 miles due south. A little before 1:00 p.m. clusters of towering cumulus started blooming just south of the rim, and I knew the lightning wouldn’t be far behind—right on schedule. I texted the group that it’s go-time, then started setting up.

I captured my first lightning strike at 1:15, and between then and 4:00 p.m. captured a total of 59 frames with lightning. I know the others who stayed also captured many nice strikes. Though first bolts were relatively distant, things started to get really good a little before 2:00. I can’t express how much fun it is to be set up and ready, waiting for the next strike, and hearing the exclamations from the group when one hits.

The first strikes started behind the South Rim, a little east (left) of straight across, more or less in the direction of (and beyond) Grandview Point. Gradually the activity moved to the right and closer, approaching the rim, with the strikes increasing in frequency, proximity, and size as they moved. The quantity and volume of the exclamations increased correspondingly. In the nearly two hours of peak activity, the best stuff happened south and southwest of our position.

The two things that I wish for most in a lightning image is a bolt that lands inside the canyon, and capturing a bolt’s actual point of impact. This image checks both boxes. You can clearly see the lightning strike several hundred feet below the rim, and while it might not be clear in this downsized jpeg, my full-size original clearly shows the red/orange point of impact, as well as a fainter branch landing even farther down.

Another thing I love about this image in particular (and one other very similar capture titled “Rim Shot” in the gallery below), is the distance it traveled, and the circuitous route it took. Those familiar with Grand Canyon might be interested to know that this bolt emerges from the clouds more or less above Pima Point on Hermit’s Rest Road, and after more random direction changes than a frightened squirrel, finally smacks the wall a few hundred feet below Yavapai Point, about 5 horizontal miles away. Pretty cool.

Epilogue

Given our successful Friday, Curt and I hit the road for home Saturday morning. But I did keep in contact with others, and the reports were that the Saturday lightning was at least as good as Friday.

In a few days I’ll post Part 2, with more images from this day, plus an updated explanation of the science of lightning.

Join me for next year’s Grand Canyon lightning chase

Lots of Lightning

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: lightning, North Rim, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V, South Rim Tagged: Grand Canyon, lightning, Monsoon, nature photography, thunderstorm

My Favorite Things

Posted on August 28, 2022

Maria von Trapp had them, you have them, I have them. They’re the favorite places, moments, and subjects that provide comfort or coax a smile no matter what life has dealt. Not only do these “favorite things” improve our mood, they’re the muse that drives our best photography. Sometimes they even inspire dreams about making a living in photography.

But sadly, turning a passion into a profession often comes at the expense of pleasure because suddenly earning money is the priority. When I decided to make photography my livelihood, it was only after observing other very good (formerly) amateur photographers who, lulled by the ease of digital photography, failed to anticipate that running a photography business requires far more than taking good pictures. Rather than an opportunity for further immersion in their passion, their new profession forced them to photograph not for joy, but to pay the mortgage and put food on the table. And with the constant need for marketing, networking, bookkeeping, collections, taxes, and just plain keeping customers happy, these newly minted photographers soon found that precious time remained for the very thing that led them to become photographers in the first place.

Nearly 20 years ago (yikes), armed with these observations I changed from photographer to Photographer. After seeing what this change had done to others, my transition was founded on a vow to photograph only my favorite things.

It shouldn’t take much time in my galleries to figure out where I find my photographic joy. I could point to locations like Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and New Zealand, but even more important to me than locations are the natural phenomena that fascinate me. Whether celestial or terrestrial, I find myself inexorably drawn to the natural processes that created and affect the world we share.

The why of this starts with growing up in a family that camped for our vacations—I just have lots of great memories of nature. But the other significant factor behind my favorite photographic subjects comes from a fascination with the physical sciences that started in my single-digit years with an interest in comets, and quickly grew to include pretty much anything in the night sky. But even then I wasn’t satisfied with simply looking at the night sky, I wanted to understand what was going on up there. And with that came a realization that Earth is actually part of the cosmos, and soon I was reading about geology and meteorology and pretty much any other ology that had to do with my place in the Universe.

All of this came before I ever picked up a camera. But it might explain why I feel so strongly actually understanding the things I photograph—if they give me join, they’re worth knowing. Whether it’s lightning, reflections, the Milky Way, rainbows, a beautiful location, or whatever, I’ve reached the point where I simply won’t post an image of something I don’t understand.

And because I enjoy writing as much as I enjoy photography, you may have noticed that I also virtually never share an image without writing something about it. I know a lot of people just follow my blog to see my images, and that’s totally fine. But these really are my favorite things in the world, and I truly appreciate that you’ve taken the time to view, and (especially) to read this far.

Keeping in that spirit, here’s a little information about lightning, excerpted from my Lightning Photo Tips article:

A lightning bolt is an atmospheric manifestation of the truism that opposites attract. In nature, we get a spark when two oppositely charged objects come in close proximity. For example, when you get shocked touching a doorknob, on a very small scale, you’ve been struck by lightning.

In a thunderstorm, the up/down flow of atmospheric convection creates turbulence that knocks together airborne water (both raindrops and ice) molecules, stripping their (negatively charged) electrons. Lighter, positively charged molecules are carried upward in the convection’s updrafts, while the heavier negatively charged molecules remain near the bottom of the cloud. Soon the cloud is electrically polarized, with more positively charged molecules at the top than at the base.

Nature really, really wants to correct this imbalance, and always takes the easiest path—if the easiest path to electrical equilibrium is between the cloud top and cloud bottom, we get intracloud lightning; if it’s between two different clouds, we get intercloud lightning. And the less frequent cloud-to-ground strikes occur when the easiest path to equilibrium is between the cloud and ground.

With lightning comes thunder, the sound of air expanding explosively when heated by a 50,000-degree jolt of electricity. Thunder travels at the speed of sound, a pedestrian 750 miles per hour, while lightning’s flash zips along at the speed of light, more than 186,000 miles per second—nearly a million times faster than sound.

Knowing that the thunder occurred at the same instant as the lightning flash, and the speed both travel, we can calculate the approximate distance of the lightning strike. While we see the lightning pretty much instantaneously, regardless of its distance, thunder takes about five seconds to cover a mile. So dividing by 5 the number of seconds between the instant of the lightning’s flash and the arrival of the thunder’s crash gives you the lightning’s approximate distance in miles (divide by three for kilometers).

But anyway…

About this image

As a lifelong Californian, lightning was just something to read about, and maybe see in movies, but rarely viewed in person. And photographing it? Out of the question.

That changed in 2012 when Don Smith and I traveled to the Grand Canyon with our brand new Lightning Triggers and absolutely no clue how to photograph lightning. We returned with enough success to be completely hooked on lightning photography, and a plan to offer Grand Canyon photo workshops focused on the Grand Canyon monsoon and (fingers crossed) lightning. After a few years Don cut back on his schedule and dropped most of his domestic workshops (we still partner for New Zealand and Iceland workshops), but I’ve continued with the Grand Canyon Monsoon workshops. This year I did two Grand Canyon Monsoon workshops, the second of which was probably my most memorable lightning workshop so far—if not for the quantity of the lightning (very good but not record breaking), certainly for the quality.

The image I’m sharing today came on that workshop’s penultimate evening, and came the day after a similarly spectacular lightning show at Cape Royal (I blogged about it two weeks ago). At Cape Royal I commented that this was one of the top five lightning shoots I’ve ever had. Little did I know…

The following night we rode the shuttle out Hermit’s Rest Road, stopping first at the very underrated Pima Point. After spending nearly an hour at Pima, pointing at a potential cell that only teased us, we packed up and headed to Hopi Point for sunset. There really wasn’t much going on when we got there, but the clouds were nice and the sky looked promising for a good sunset.

As sunset approached, what may have been the remnants of the cell that had disappointed us at Pima Point seemed to regroup and start moving from left to right across our scene and toward the canyon. The first reaction to this development was, “No big deal” (fool me once, …). But just one relatively weak bolt was enough to send us all scrambling for our Lightning Triggers. Everything after that is pretty much a blur because as the storm slowly advanced, some unseen force turned the lightning up to 11—both its frequency and intensity.

In my July 31 post I shared an image of a rogue Hopi Point lightning bolt that was somehow perfectly placed above the canyon right at sunset. As the only lightning we saw all evening, this one felt like a gift from heaven. This evening’s lightning was similarly positioned, but much bigger, and I lost track of the number of bolts we saw: double strikes, triple strikes, serpentine strikes—pretty much a lightning photographer’s entire wish list all in one show.

Hopi Point access is by shuttle-only, which means if we miss the last shuttle we’re walking more than 2 miles back in the dark. The lightning was still going strong when we hopped onto the final shuttle in growing darkness, but given what we all knew we had, no one was too disappointed.

Here are a couple of images from Cape Royal the night before this image

And here are the two more images from this night’s shoot at Hopi Point

I realize that I get far more excited about lightning than the average person. And I’m truly sorry for sharing so many lightning images, but you’ll just have to understand that not only is lightning a novelty for me, and (please) recognize my good fortune for being able to make my living photographing nothing but my favorite things.

These Are A Few Of My Favorite Things

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Category: Colorado River, Grand Canyon, Hopi Point, lightning, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7RIV Tagged: Grand Canyon, Hopi Point, lightning, Monsoon, nature photography, thunderstorm

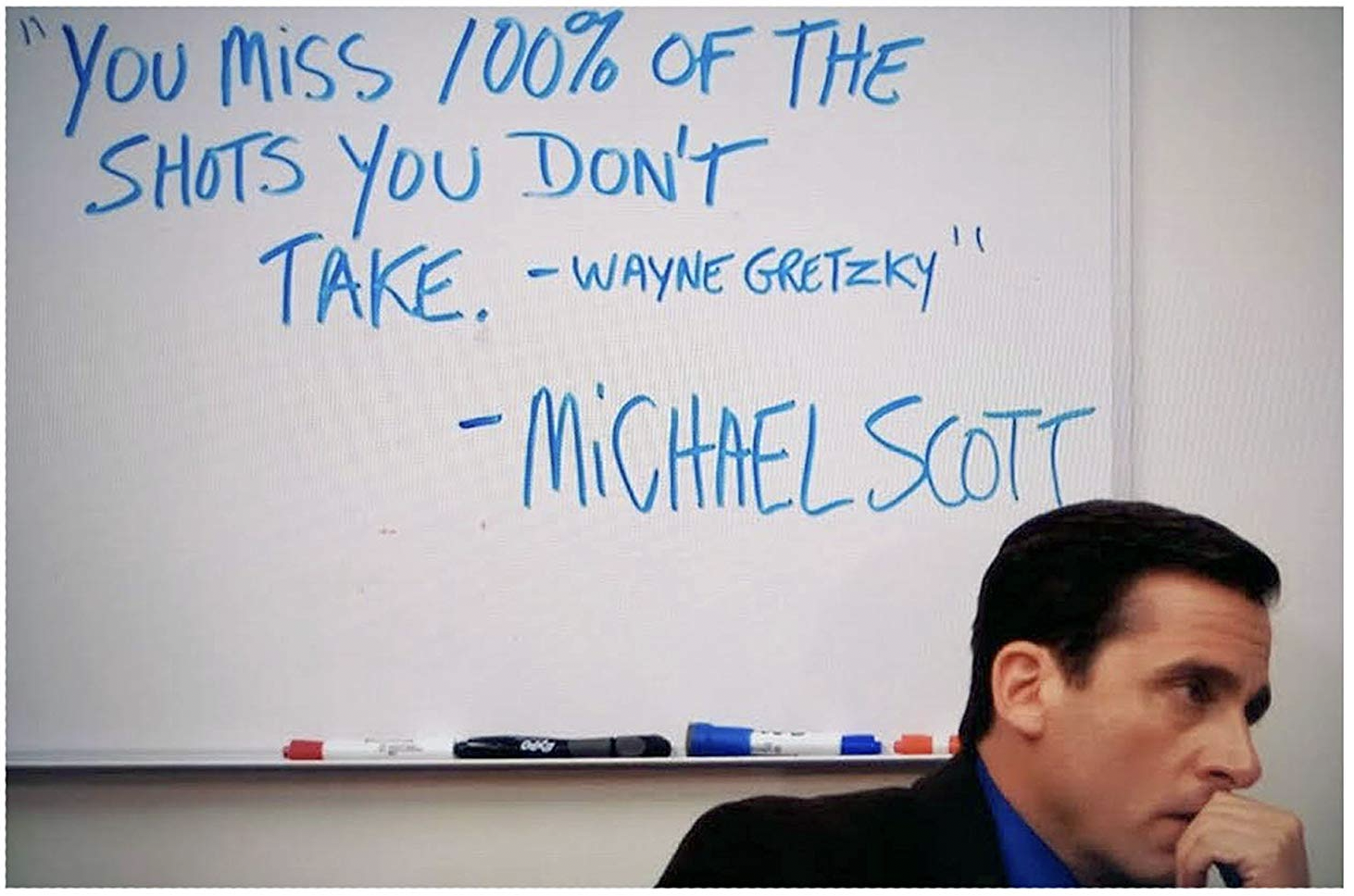

What Would Michael Scott Do?

Posted on March 20, 2022

“You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take. — Wayne Gretzky” — Michael Scott

Rules are important. The glue of civilization. Bedtime, homework, and curfews constrained our childhood and taught us to self-police to the point where as adults we’re so conditioned that we honor rules simply because we’ve been told to. (Who among us doesn’t always wait for the signal to change, even with no car or cop in sight?)

As important as this conditioning is to the preservation of civil society, rules can sometime keep us from taking shots that might have turned out to be special. Rather than trusting their own instincts, less than confident photographers are often held back by blind adherence to the (usually) well-intended photography “experts” proliferating online, in print, and maybe even in your very own camera club. These self-proclaimed authorities love nothing more than to issue edicts for their disciples to embrace. But my general advice to anyone seeking photography guidance is to beware of absolutes, and when you hear one, run (don’t walk) to the nearest exit. The truth is, there are very, very few absolutes in photography. (Remove the lens cap?)

A more insidious hindrance to photographers is our own rules—things we truly believe to be true. These are like training wheels that served us so well at the start that we never considered removing them: the rule of thirds, never blow your highlights, don’t center the horizon, everything sharp from front to back, avoid bright sunlight, just to name a few. But they’re insidious because, while they may be founded on some basic truth, they also hinder our growth. Like walls that give comfort by protecting us from intruders, photographic rules obscure the horizons of our creativity.

The truth is you often don’t know whether an image will work until you click the shutter—and sometimes not even until you get home and look at it on your computer. The more you’re able to turn off that internal editor (who keeps repeating all the rules spewed by others), the better your results will be. Just remember this: If you’re not breaking the rules, you’re not being creative.

The image I share above might never have happened had I followed a couple of rules—one I hear all the time from well-intended photo judges, another I often impose on myself: A photo judge might ding it for the centered lightning bolt and (more or less) centered horizon; and I may have never had the opportunity to photograph this beautiful thunderhead at all had I not overcome my personal aversion to photographing in midday light.

The afternoon I captured this came during one of three Grand Canyon Monsoon photo workshops last summer. The sky was blue and the forecast for lightning not so great, but we headed out toward Desert View that afternoon anyway. Shortly after pointing east along the rim on Highway 64, I saw this towering thunderhead blooming in the distance. Given all the twists and turns on the road, I wasn’t even sure at first it would be in our scene at Desert View. And since our destination was still about 30 minutes away, I was even less confident that even if the thunderhead was over the canyon, it would still be active by the time we got there.

I was assisted in this workshop by my friend and fellow photographer Curt Fargo. I can always count on Curt, realtime lightning app open, relaying instant reports on the activity as we drive, and it wasn’t long before he determined that thunderhead had to be where the app showed a lot of lightning activity about 15 miles up the canyon from Desert View—not exactly close, but at least the viewing angle would work. At that point all we could do was drive, watch the cloud, and pray it didn’t peter out before we got there. (Why is the speed of the car in front of you always inversely proportional to the amount of hurry you’re in?)

As you can see, we made it. Rather than drive all the way out to Desert View, we stopped at the first good view of the canyon and thunderhead—Lipan Point, about two miles closer with a much shorter walk to the rim. By the time we were set up the lightning activity had peaked, but we still got a few strikes. We also got to watch this cell absolutely dump an ocean of water on one spot for nearly an hour, no doubt creating a significant flash flood for whatever canyon drained it. This is the only image I captured that included the entire thunderhead.

The moral is, whenever you find yourself basing composition or exposure decisions on pre-conceived ideas (either your own or others’) of how things should be, just slow down a bit and challenge yourself to break the rules. Go ahead and get your standard shot, but then force yourself to try something outside your comfort zone. And remember Michael Scott.

Here’s my guide for photographing lightning

Breaking the Rules

Frozen in Time

Posted on September 26, 2021

Lightning Strike, Brahma Temple, Grand Canyon

Sony a7RIV

Sony 24-105 G

1/4 second

F/8

ISO 250

I’ve always been intrigued by still photos’ ability to reveal aspects of the natural world that are missed by human vision. A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the camera’s ability to, through long exposures, blur motion and reveal unseen patterns in moving water. And last week I shared an image that used a long exposure to capture the Milky Way above crashing Hawaiian surf, a 20-second exposure that blurred that explosive wave action into a gauzy haze.

But I think my favorite still image motion effect is probably freezing a lightning bolt—an ephemeral phenomenon that comes and goes so quickly that it is already a memory before it even registers to my brain. The thrill of seeing a lightning strike always delivers a jolt of adrenalin, but it’s not until I can spend time with an image that froze it in time that I appreciate all that happens in a lightning bolt. Multiple prongs, meandering patterns, delicate filaments—each bolt seems to have a personality of its own.

For me, the holy grail of lightning captures is the splash of light that occurs at the primary bolt’s instant of contact with terra firma. Not only is getting the precise timing difficult, the strike also needs to be fairly close, and on a surface that’s angled to face my vantage point.

The lightning in this image checked those boxes, striking just a couple of miles away on the diagonal slope of Brahma Temple facing me. It was one of many lightning strikes captured on the second day of my first (of three) Grand Canyon monsoon workshops earlier this summer. On the day prior we’d had a nice lightning shoot just as the workshop started, but the storm that afternoon had moved parallel to the rim, staying near the South Rim, at least ten miles away.

This afternoon’s storm started in more or less the same area of the South Rim, but crossed the canyon, approaching less than two miles from where my group had set up on the view decks outside Grand Canyon Lodge. Protected beneath an array of lightning rods, and just a few feet from the safety of the fully enclosed lodge Sunroom, this spot is the location of some of my workshop groups’ closest lightning encounters. This afternoon was added to that list.

I usually prefer photographing lightning that’s across the rim, distant enough that we often don’t hear the thunder. At most locations, when the lightning gets as close as it got this afternoon, I’ve already rounded people up and herded them indoors or to the relative safety of the cars. But here I have (barely) enough cellular service to monitor the distance of each strike with my lightning app, and keep everyone apprised of its proximity, so they can make their own call on when to retreat.

Preparing to photograph lightning is a matter of setting up my tripod with my camera and Lightning Trigger, composing a frame that includes the area most likely to receive the next bolt, focusing and metering the scene, then standing back and waiting for the strike (not unlike fishing).

If everything is set up correctly, lightning photography a hands-off endeavor—when it senses lightning, my Lightning Trigger fires my camera’s shutter, then just waits patiently to do it again with the next lightning. So when this bolt hit, I wasn’t even with my camera—I was checking with others in my group. When it struck, it was the closest we’d seen so far. It was also farther to the left than any previous strike—so far, in fact, that I wasn’t even sure it was in my frame.

It wasn’t until I was processing my images that I found that I had indeed captured it. Not only that, this bolt struck close enough, on an exposed surface that was in perfect view for me to capture the precise point of contact in all of its glory. Unfortunately, it was on the far left side of my horizontal frame. This is when I appreciate having my Sony a7RIV, probably the best lightning camera made today. Not only do the Sony bodies have the fastest shutter lag (the time it take for the shutter to respond after receiving the instruction to fire), but 61 megapixels provides a crazy amount of latitude for cropping.

I usually like to get my crop right before capture, but I sometimes need to make an exception when photographing lightning, because I’m never sure where in the frame the lightning will land. In this case, having my lightning strike so close to the left side of a horizontal frame made the image feel very off-balance. To fix the problem, I simply turned it into a vertical composition, eliminating everything on the right 2/3 or the original composition. But with 61 megapixels to play with, the final product was still more than 25 megapixels—more than enough for pretty much all of my uses, including large prints.

Read my tutorial on photographing lightning

Frozen in Time

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Category: Grand Canyon, lightning, Lightning Trigger, North Rim, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7RIV Tagged: Grand Canyon, lightning, Monsoon, nature photography, North Rim, thunderstorm

(More) Lightning Lessons

Posted on August 22, 2021

Downpour and Lightning, Desert View, Grand Canyon

Sony a7RIV

Sony 24-105 G

1/8 second

F/8

ISO 50

This post is all about different aspects photographing lightning—some of the stuff I write about here is covered in much more detail in my Lightning Photo Tips article, so you might want to start there

I’ve been photographing lightning at the Grand Canyon (especially) and elsewhere for 10 years, but I’m happy to say that I’m still learning. While going through my images from this year’s recently completed Grand Canyon monsoon workshops, it occurred to me that now might be a good time to share a couple of this year’s insights.

Lightning Trigger (where it all begins)

You simply can’t photograph daylight lightning consistently without a lightning sensor that detects the lightning and triggers your shutter. And if you follow my lightning photography at all, you’ve no doubt heard me singing the praises of the Lightning Trigger from Stepping Stone Products in Colorado. (There are a lot of lightning sensors out there, but since Lightning Trigger is trademarked, this is the only one that can legally use “lightning trigger.”) I don’t get anything from Stepping Stone for my endorsement, I just know it’s in my best interests to give everyone in my groups the best chance to photograph lightning, and so far I haven’t found anything that comes close the the success of the Lightning Trigger.

But despite my strong advice to the contrary, every year one or two people will show up with a sensor that’s not a Lightning Trigger. And every year, these are the people who have the poorest lightning success. Sometimes the reason for failure is obvious—like a sensor that allowed the camera to go to sleep after 30 seconds of inactivity. But usually the reason isn’t quite so obvious—I just know that the people with the “other” sensors are much more likely to get shut out. This year was no exception.

The first workshop (of three) started with a bang, with an active storm building across the canyon, about 12 miles away, just before the workshop orientation. Because lightning trumps everything in these monsoon workshops, I cancelled the orientation and herded everyone to the view deck behind Grand Canyon Lodge (I’d advised them to show up with their gear for this very reason), frantically flying around from person to person to introduce myself, help them set up, and make sure their cameras were clicking with each lightning strike.

After about 15 minutes, all but one seemed comfortably settled in, excitedly reporting that their camera was responding to each bolt. In addition to my one participant who wasn’t having success, there was a woman who wasn’t in my group trying to photograph lightning with a sensor—she too was growing frustrate because her camera seemed be ignoring the lightning too. The one thing these two people had in common? Perhaps you already guessed: they were the only two not using a Lightning Trigger.

I actually tried to help both of them troubleshoot the problem, starting with confirming that everything was plugged in right, then quickly moving to lots of fiddling with camera settings, cables, and batteries. But since I could make their sensors respond with the TV remote I always have nearby when I photograph lightning (the easiest way to test a Lightning Trigger in the field), I wasn’t real optimistic—if the remote triggers the camera, the problem is unlikely to be the connection, power, or camera. That leaves the sensor itself as the most likely culprit.

When leading a workshop I don’t have lots of time to get too scientific with my troubleshooting, but think I solved the mystery the next day, when a similar storm started up at about the same time in more less the same place. For the second day in a row we all set up on the Grand Canyon Lodge view deck, and for the second day in a row, the only person in the group whose camera wasn’t responding was the person with the off-brand sensor. (The woman from the prior day wasn’t there.)

While the prior day’s storm moved laterally across the canyon, this storm moved in our direction, approaching to within a couple of miles (and eventually driving us all for cover in the lodge). When, as the storm got closer, the rogue sensor started triggering its camera, I realized that what sets the Lightning Trigger apart from its competition is most likely its range.

My superior range theory got more confirmation on the South Rim a couple of days later. Driving out toward the South Rim’s eastern-most views for our sunset shoot, my eyes were drawn to a massive thunderhead blooming in the distance. With the forecast offering no hope for lightning to chase, that evening’s plan was to make a couple of quick stops at Lipan and Navajo Points, before finishing with sunset at Desert View. But pulling into Lipan Point it was instantly apparent that the thunderhead was straight up the canyon—we weren’t there long before we could also see it was delivering lightning. (One reason I tell everyone to always carry their Trigger, regardless of the forecast.)

Because this turned out to be a spectacular show that lasted until sunset, we never left Lipan Point. Unlike the previous storms, where the lightning was front-and-center in every composition, the lightning this evening was much farther away—between 22 and 25 miles distant, according to the My Lightning Tracker app on my iPhone. While all the Lightning Triggers didn’t seem to miss a single bolt (“not missing” in this case just means firing when there’s a visible bolt—you’ll see below that this is by no means a guarantee that the bolt will be capture), our rogue sensor not seem to see the lightning at all.

Further confirmation of the Lightning Trigger’s range came in the third workshop, when we were photographing lightning more than 30 miles away. I’ve had success with the Lightning Trigger and distant lightning in the past, but this was the first time I’ve had an app (and cellular connectivity) to actually pinpoint the location and distance.

Slower than the speed of lightning (or, About this image)

One of the most frustrating things about photographing lightning is not capturing a spectacular strike. The first half of the capture equation is a sensor that sees the lightning and triggers the camera (see Lightning Trigger discussion above); the other half is having a camera that responds quickly enough to the click instruction from the sensor. And as I’ve said before, all the three major camera brands are fast enough, but where lightning is concerned, the faster the better—and it’s impossible to be too fast. FYI, according to Imagining Resource, Sony Alpha camera’s are the fastest, followed closely by Nikon, with Canon a fair amount slower (but usually not too slow).

I can confirm the Imaging Resource data. While I had good success while using Canon my first few years photographing lightning, my success rate has been noticeably higher since switching to Sony in 2014 (my first Sony lightning shoot was in 2015). But despite a faster camera, the frustration with missed lightning hasn’t disappeared completely. Usually it’s just one or two here and there—I just shrug my shoulders because I know I’ll probably get the next one. But in this year’s third workshop, one especially frustrating shoot got my attention.

The third group didn’t have any lightning luck on the North Rim for our first two days, but the forecast looked more promising for the South Rim half of the workshop. Unfortunately, the best chances were forecast for the day of our 4-hour rim-to-rim drive. Since it’s such a nice drive, I usually give everyone the whole day to make it, suggesting stops then setting them free after the sunrise shoot—we don’t gather as a group again until late afternoon on the other side. But with such a promising lightning forecast, this time I had everyone meet me at Desert View, the first South Rim vista when driving from the North Rim, at 1:00 p.m., hoping that we’d get the workshop’s first shot at lightning.

Setting up on the rim just west of the Desert View Watchtower, we just hung out for awhile, waiting for something to happen. Our patience was rewarded after about an hour, when a few people in the group saw lightning in the east. This was out toward the Painted Desert—not actually over the canyon, but close enough to get lightning and the canyon in one frame. Better yet, it soon became clear that the storm was moving, not just toward the canyon, but toward one of my favorite Grand Canyon views.

This whole shoot lasted at least a couple of hours. Standing there on the rim, we watched the lightning first migrate north, eventually intersecting the canyon just beyond the Little Colorado River confluence. It then started to shift westward, crossed the canyon, continued drifting west, and everyone was pretty excited. That is, until we realized that it was also getting closer. We were preparing to retreat when a bolt hit inside the canyon, less than two miles away, sending our sense of urgency into overdrive.

Since this was this group’s first lightning, everyone was especially excited when their camera clicked with each lightning bolt. Though I knew no one would get every single bolt, with several dozen visible strikes, I was pretty confident everyone’s success numbers would be in the double digits—mine included.

But checking my images in my room that night, I was disappointed to count only three frames with lightning. I was just going to write it off as one of those things—perhaps my LT battery was weak, or maybe I was too focused on working with others in the group (in other words, doing my job) to adjust my composition frequently enough to track the continuously shifting storm.

But when I mentioned my poor success to Curt, my assistant on this trip, he expressed similar results. And talking to the group the next day, we learned that no one else got more than a (very small) handful of strikes. How could a dozen people using a lightning sensor that years of experience proves works reliably, on a variety of cameras, have such similarly poor results on just one shoot? Adding to the mystery, it became clear by the images shared in the image review that the lightning everyone did capture, was all the same strikes. What’s going on?

One of the things I love most about working with Curt is that he’s as inquisitive and bulldog-tenacious tracking down these mysteries as I am. We got to work researching what could be going on, both on our own, and together on a one-hour conference call with Rich at Stepping Stone, the mastermind behind the Lightning Trigger.

Rich suggested that it could be that we encountered a storm that was mostly positive lightning. Positive lightning, which comprises about 5 percent of lightning strikes, usually spends all of its energy in a single stroke, making that one stroke very bright, but also much faster from start to finish. He thought that maybe the lighting was done before everyone’s cameras could react. That made sense.

But after a little research on positive lightning, I (tentatively) ruled it out as our culprit because: 1) I saw nothing that indicates that positive lightning is storm-specific (though I’m open to correction); 2) positive lightning originates near the top of the cloud, and I saw no sign of that in this storm; 3) positive lightning tends to come near the end of the storm, and we photographed this one from start to finish; and finally, 4) positive lightning typically strikes outside the main rain band, and we saw very little of this.

But that conversation with Rich convinced me that our problem this afternoon had to indeed be a caused by lightning that was too fast for our cameras. And after mulling that thought for awhile, then digging deeper into my lightning resources, I theorized that we’d probably just encountered a storm that didn’t have as much juice as the typical monsoon storms I’m accustomed to.

This makes sense if you understand that a typical negative lightning strike that looks like a single bolt to the eye (or camera), is actually a series of strokes following the same channel. The number of strokes in a single lightning bolt varies with the amount of energy the lightning needs to release—the more strokes, the longer the strike seems to last. (As an interesting aside, earlier in the trip Curt got accidental confirmation of lightning’s multiple stroke aspect when, with his camera set to Continuous rather than the Single Shot that I use, he got the same lightning bolt in two, and at least once, three contiguous frames.)

The jury is still out on this theory, but it makes sense. If I learn anything more, I promise to share it. Right now I’m in the process of updating the Lightning Photo Tips article with this and more insights gained since the last update, so that’s the best place to check for new information.

Oh, and the image I share here was one of my three successes that afternoon, so I’m not really complaining.

2021 Grand Canyon Monsoon Highlights (processed so far)

Spoiler Alert: It’s not just lightning

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Category: Colorado River, Desert View, Grand Canyon, lightning, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7RIV Tagged: Desert View, Grand Canyon, lightning, nature photography, thunderstorm

More Monsoon Magic

Posted on August 2, 2021

Lightning V, Grand Canyon

Sony a7RIV

Sony 24-105 G

1/10 second

F/8

ISO 160

Greetings from the Grand Canyon. It’s pretty hard to post a blog in the middle of a workshop, and downright near impossible when the Internet is down and your cellular carrier has capped your roaming data at 200 megabytes (which I ripped through in 3 days, with only 12 days to go—thank you very much, T-Mobile). But here I am, a day late, with some thoughts on improving your lightning photography and an update on the Grand Canyon monsoon activity so far.

Subtracting one year lost to COVID, this is my eighth year doing at least two monsoon workshops at the Grand Canyon—this year it’s three. In previous years I’ve done these workshops in partnership with my friend and fellow Sony Artisan Don Smith; this year I’m flying solo, grateful for the assistance of my friend (photographer, sensor cleaning guru, and essential lightning tracker) Curt Fargo.

Being solely responsible for the success and wellbeing of a dozen photographers isn’t without its stress. Despite the always breathtaking beauty that comes with the Grand Canyon monsoon, make no mistake about it: people sign up for these workshops for the lightning. And while I make it very clear that enrollment comes with no guarantees, and do my absolute best to prepare everyone well in advance, I still stress until each person in my group has captured at least one bolt.

Many factors contribute to lightning success, but when you measure success by the results of a dozen other people, things get even more complicated. And since we’re in the midst of lightning season for most of the Northern Hemisphere, I thought I’d share my thoughts on maximizing lightning success. In no particular order, here are my essential lightning preparation tips:

- The right equipment

- Mirrorless or DSLR camera with minimal shutter lag: Sony is the fastest, followed closely by Nikon; Canon is fast enough. I don’t have enough experience with the other brands to know which work well and which don’t. And new cameras come out so fast, my information isn’t necessarily current, so the other manufacturers could have upped their shutter-lag game (or not). One more thing: it helps to have a camera that goes down to ISO 50 (this often needs to be turned on in the menu).

- 24-105 (ideal) or 24-70 lens: Since you don’t know exactly where the lighting will land, it’s best to compose a little loose and crop in post, making long telephotos of limited use. And if you find yourself needing to go wider than 24mm, you’re too close (trust me).

- Lightning sensor: No one is fast enough to consistently capture lighting without a device that detects lightning and triggers the shutter. Period. There are a lot of lightning sensor options, but the only one I’ve seen work reliably, at a range of up to 40 miles, is the Lightning Trigger. (FYI, this name is trademarked, so it’s the only lightning sensor that can legally be called Lightning Trigger.) I recommend Lightning Trigger to all of my workshop students, and always hold my breath when someone shows up with something different. (I get no kick-back or other benefit from this recommendation—it just makes my life much easier when workshop participants use something I know works.)

- Polarizer or (even better) a 3- to 6-stop neutral density filter: For lightning, sometimes you need a little help getting to a slow enough shutter speed. I use a 6-stop Dark Polarizer from Breakthrough Filters.

- Sturdy tripod: You’ll be shooting at shutter speeds no faster than 1/15 second. Not only that, there’s a lot of waiting in lightning photography, and your camera must be primed for action at all times, making hand-holding impractical (and downright uncomfortable).

- Wet weather gear: I rarely get wet photographing lightning because I try not to be in the storm I’m photographing (which is one thing that makes the Grand Canyon, with its distant views, such a great lighting location), but sometimes I get caught out in the rain.

- Waterproof hat, parka, pants, shoes

- Umbrella

- I haven’t found a rain cover for my camera gear that isn’t more trouble than it’s worth, a problem compounded by having my Lightning Trigger mounted atop my camera. In the rare situation that I decide to stay out in the rain and shoot, I just use my umbrella (AKA, portable lightning rod).

- Equipment knowledge: When photographing something as fickle and ephemeral as lightning, all the equipment in the world won’t do you much good if you don’t know how to use it without conscious thought.

- Exposure knowledge: Lightning photography requires very specific shutter speeds that vary with conditions. Not only do you need to get the exposure right, you have to know how to do it in a very specific shutter speed range.

- Weather/lightning knowledge

- Learn how to identify the cells will deliver lightning.

- Recognize the direction the lightning is moving.

- The faster you can recognize and respond to potential lightning, the better your results will be. If you wait until a strike hits before heading in that direction, you’re asking for disappointment.

- Weather/lightning resources

- National Weather Service: There may be other reliable sources, but most use the NWS data. The NWS is far from perfect (like all weather forecasting entities), but it’s more consistently reliable than any other source.

- Real-time lightning reporting app: This is a huge benefit that allows me to monitor storm and lightning activity, on a scale ranging from macro (national) to micro (local). Many apps offer this service, but the one I use and consider absolutely essential is My Lightning Tracker Pro. (I’m not a tester, so like all of my recommendations, this endorsement is based on personal experience and comparison to other apps I’ve used and observed, not any systematic tests.)

- Location knowledge

- Know when the lightning tends to start.

- Know where the lightning is most likely to strike.

- Know the best/safest vantage points and how to get to them quickly.

- Escape routes: Don’t photograph a location without knowing where to retreat when lightning gets too close.

I do my best to fill my groups with all this knowledge and more, before we start. Even though we’ve been been shut out a few times, I’ll take a little credit for the overall success rate—so far my workshop lightning batting average (everyone in the workshop gets at least one strike) is probably somewhere around .700, and in a few workshops some, or even most, had a success.

But really, regardless of the preparation, the biggest factor in capturing lightning in a workshop that was scheduled more than a year in advance, comes down to just plain luck, and like all weather phenomena, lighting is random. But preparation does give you the best possible chance of success if you’re lucky enough to get a chance. And honestly, it’s the unknown that makes chasing lightning so much fun.

Read my complete lightning photography how-to guide in my Photo Tips Lightning article.

Back to the present

So anyway…

This morning I wrapped up the first of three consecutive Grand Canyon monsoon workshops. To say that we started with a bang would be an understatement. For just the second time since I started doing this, we postponed our 1 p.m. orientation because the lightning started around noon. Fortunately, a couple of days before our start I’d sent an e-mail letting everyone know this was possible, and to show up at the orientation with gear and prepared to hit the ground running. And that’s what we did.

For the workshop’s first two hours, we photographed a very active electrical storm across the canyon from our North Rim perch at Grand Canyon Lodge. By the time we were done, I’d captured 35 frames with lightning, only one person in the group didn’t have at least one lightning strike (most had many more)—the person who showed up with a lightning sensor that wasn’t a Lightning Trigger.