Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Going Out a Winner

Posted on January 17, 2026

There was nothing easy about this picture. Milky Way photography in general is a challenge, but trying it at the bottom of Grand Canyon is especially harrowing. In addition to the standard Milky Way photography difficulties, like insufficient light essential for composition and focus, any kind of night photography at the bottom of a mile-deep hole adds another level of dark.

In this extreme darkness, some locations are worse than others, and navigating to this one in particular was difficult enough to put it on the fringe of my safety comfort zone. Not only did getting here require a longer than usual walk on uneven and sometimes trailless (is that a word?) terrain, the last section was along a series of narrow ledges where a single misstep might result in a sudden plunge into the Colorado River. Oh, and as if all that wasn’t enough to test me, on the entire walk out here this night, I couldn’t push down the thought that the name of this particular camp is Rattlesnake.

But I was especially motivated to make this shoot work, because…

I knew before the trip started that this, my tenth Grand Canyon raft trip, would be my last one. Rafting Grand Canyon had been a bucket-list item for as long as I could remember, but when I scheduled my first trip way back in 2014, I had no plan to continue once it was it off my list. But, for many reasons, that initial experience so far exceeded expectations, I vowed to continue doing it until people stopped showing up. Fast forward nine more trips: turns out, I’m the person who will stop showing up…

Let me explain. The trip still fills, but not nearly as quickly as it did those first few years, when I already had a waiting list for the next year before the current year’s trip even pushed off. And with costs rising faster than I’ve been able increase the price (see slowing enrollment reference in the previous sentence), and understanding that I’m on the financial hook for a full trip whether or not it fills, somehow my Grand Canyon raft trip had become the most stress-inducing offering on my schedule. So, while I still love the whole rafting experience as much as ever, when I decided to pare a few workshops from that schedule, it seemed like ten (!) Grand Canyon raft trips was a nice round number to go out on.

But I will miss it. Between the sights, the rapids, the guides, and the fantastic people I got to share it all with, it’s pretty difficult to single out one thing I’ll miss most about rafting Grand Canyon. But hold a gun to my head, and I’d have to say it will be the night sky filled with more stars than I’ve ever seen, and so dark the Milky Way actually casts a shadow.

As desperately as I craved a good Milky Way experience (and when I say Milky Way, I refer specifically to our galactic core) on this farewell trip, I always go in knowing that, for many reasons, Milky Way success is far from a sure thing. Even though it’s always a priority, before this one, I’d had trips that had two nice Milky Way shoots, one nice Milky way shoot, and zero nice Milky Way shoots.

First obstacle is that, despite Grand Canyon’s typically clear skies, clouds do happen—I had two trips with so many clouds we never even saw the Milky Way. But even when the sky is clear every night, we still need a little luck to even see the galactic center because, from most campsites, the Colorado River’s general east/west orientation through the canyon puts views of the southern horizon (where the Milky Way hovers in May) behind the looming south wall. It helps that over the years I’ve been able to identify a handful of campsites that are either on the north/south trending Marble Canyon section of the canyon (where we spend our first two nights), or (more rarely) on a south-facing bend in the river. But they’re few and far between.

Since all Colorado River campsites in Grand Canyon are first-come, first-served, my trips can never count on getting one with a Milky Way view. And the Colorado River is unforgivingly one-way—if your first choice campsite is taken, there’s no way to return to that wide open second choice campsite you passed two miles back. This fact sometimes forces us to settle for whatever campsite is available. And with a schedule to maintain, even coming upon an empty ideally oriented campsite is of no value if we’re floating past it at 11 a.m. because we don’t have enough wiggle room in our schedule to lose a half day of rafting.

With all this in mind, at the start of each trip I powwow with the guides to explain (emphasize) my Milky Way and other photography priorities (for example, if it’s sunny, there are several key locations I only want to photograph in the full shade of early morning or late afternoon). We come up with the framework of a plan that by Day-2 is usually out the window, or at least is significantly renegotiated, as things invariably don’t go exactly as planned. And each plan change factors in downstream Milky Way possibilities.

The first thing I do after arriving at a new camp is check its Milky Way opportunities—specifically, I identify south and whether it’s behind a canyon wall (bad), or between the two walls (good). But even an open southern exposure isn’t enough—I know of at least one campsite with a great view of the southern sky, but it’s so overgrown along the river that all we get for a foreground is a bunch of scruffy shrubs. And my groups have also had several campsites where the only place to park the boats is smack in the middle of the only open view of the southern sky. So all the tumblers need to click into place for the Milky Way to work at the bottom of Grand Canyon.

If I determine that tonight’s campsite does have a good view of the Milky Way, at some point (usually at dinner) I give group the night’s Milky Way plan: where it will appear, when it will appear, and the best place to photograph it. I also give a basic Milky Way photography primer (focus, composition, and exposure tips), lecture them about the damage flashlights will do to everyone’s shots (especially red lights!), then make myself available for the inevitable, “Which lens…?,” “How do I get my camera to do…?” questions. By bedtime, most people who hope to photograph the Milky Way are ready (-ish). And of course they know where I’ll be set up if they have problems (but they’ll need to come me, because it’s too dark to safely move around to everyone).

All of my Grand Canyon night shoots are no-host: I tell people where I’ll be and roughly when I’ll be there. In May the earliest the Milky Way rises into view is around 1:30, but to avoid disturbing people who value their sleep more than I do, I never set an alarm because that might disturb those nearby who would rather sleep. Fortunately, I have no problem waking myself up at a specific time, give or take 15 minutes.

There are six nights on this trip. The way the trip usually unfolds, our best chances for the Milky Way are the first two nights, and (if we’re very lucky) the fourth night. On our first night of this trip, we ended up at a spot beneath a wall that blocked the lower half of the Milky Way, but the few of us went for it and did okay—but I knew we could do much better.

Not wanting to hang all our hopes on getting the very nice but difficult to secure campsite on night four, I felt very motivated to make the second night work. But as the afternoon wore on and we continued to encounter good campsites that were already taken, we just floated on. And there comes a point where you just have to take whatever is available so we can start the business of setting up camp and making dinner before it gets too dark. Which is why the guides were actually relieved as we floated up to Rattlesnake camp and found it open, Milky Way be damned. The first thing I did when we landed was pull out my phone and check the compass to find south, and as feared, the S-needle pointed right at a towering wall. Oh well…

But after setting up my campsite, I got my (iPhone) compass out and went exploring. My eye was on a bend in the river a few hundred yards downstream, and I wondered if it might bend far enough to the south to provide a view to the southern sky, and whether it was even possible to get down that far.

As I moved downstream, the route along the river got rockier, eventually turning into a series of sandstone ledges with a steep drop straight to the water. Each time it looked like I couldn’t go any farther downstream, I found a I found a route that got me a little farther. I was at least a quarter mile downstream before reaching a spot where I could go no farther without climbing. (A quarter mile doesn’t sound very far, but in total darkness and without a trail, it feels like forever.) Looking downstream, I saw that this vantage point still didn’t face due south as I’d hoped, but it did provide a clear view southwest. Hmmm—not ideal, but… maybe?

Checking (and re-checking) my astronomy app, I guessed (crossed my fingers) that we might have about a 45-minute window from the time the Milky Way rotated out from behind the canyon wall, until the sky started to brighten enough that we’d start losing essential contrast. And the longer I took in the entire view, the more I liked the river scene we’d be able to put with the Milky Way. If it worked.

Walking back, I took special note of the route, identifying distinctive rocks and shrubs I might be able to use as landmarks in the dark. At camp, I told my group what I’d found, and that the window of opportunity is very small (even the slightest miscalculation on my part could make a difference). I also warned the that the route out there, while only slightly treacherous in daylight, would be exponentially more-so in virtually total darkness. I also told them I’d be going for it. I finished by encouraging anyone even considering going out there in the dark to scout it and make a route plan now.

Before crawling into my sleeping bag, I got my camera and lens combo set up on my tripod and stood it next to my cot. The last thing I did before closing my eyes was set my mental alarm clock for 3 a.m.

I woke up a little before 3:00, grabbed my tripod, and made my way out. Because other people might be either shooting or sleeping, I try not to use any kind of flashlight or headlamp when walking around at night, but using only my cell phone screen to illuminate my next step, I didn’t really have much trouble finding the way, one step (as far as I could see) at time until I was there.

I was surprised and pleased to see how many people were already out there—on this trip I have a lot of non-photographers who join photographer friends and loved-ones, but I’d guess close to a third of the group was there already, and a few more joined shortly after I arrived. With no light, I poked around on the sandstone until my eyes to completely adjusted, and eventually edged my way out to the farthest ledge. Then I went to work.

I did my usual vertical (first) and horizontal composition mix, trying different ISO and shutter speed settings to give myself more processing options. I also moved around a little, eventually photographing from three different positions within about a 30-foot radius. From my first frame to my last was only 25 minutes, but by the time I’d finished, I knew I’d had a Milky Way success I so wanted on my final trip.

Category: Colorado River, Grand Canyon, Milky Way, reflection, Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM, Sony Alpha 1 Tagged: astrophotography, Grand Canyon, Milky Way, nature photography, reflection, stars

Gifts From Heaven

Posted on November 3, 2024

Heaven Sent, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS Above the Sierra Crest, Alabama Hills

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 3200

f/4

5 seconds

As much for its (apparently) random arrival as its ethereal beauty, the appearance of a comet has always felt to me like a gift from the heaven. Once a harbinger of great portent, scientific knowledge has eased those comet fears, allowing Earthlings to simply appreciate the breathtaking display.

Unfortunately, scientific knowledge does not equal perfect knowledge. So, while a great comet gives us weeks, months, or even years advance notice of its approach, we can never be certain of how the show will manifest until the comet actually arrives. For every Comet Hale-Bopp, that gave us nearly two years warning before becoming one of the most widely viewed comets in human history, we get many Comet ISONs, which ignited a media frenzy more than a year before its arrival, then completely fizzled just as the promised showtime arrived. ISON’s demise, as well as many highly anticipated comets before and after, taught me not to temper my comet hopes until I actually put eyes on the next proclaimed “comet of the century.” Nevertheless, great show or not, the things we do know about comets—their composition, journey, arrival, and (sometimes) demise—provide a fascinating backstory.

In the simplest possible terms, a comet is a ball of ice and dust that’s (more or less) a few miles across. After languishing for eons in the coldest, darkest reaches of the Solar System, perhaps since the Solar System’s formation, a gravitational nudge from a passing star sends the comet hurtling sunward, following an eccentric elliptical orbit—imagine a stretched rubber band. Looking down on the entire orbit, you’d see the sun tucked just inside one extreme end of the ellipse.

The farther a comet is from the sun, the slower it moves. Some comets take thousands, or even millions, of years to complete a single orbit, but as it approaches the sun, the comet’s frozen nucleus begins to melt. Initially, this just-released material expands only enough to create a mini-atmosphere that remains gravitationally bound to the nucleus, called a coma. At this point the tail-less comet looks like a fuzzy ball when viewed from Earth.

This fuzzy phase is usually the state a comet is in when it’s discovered. Comets are named after their discoverers—once upon a time this was always an astronomer, or astronomers (if discovered at the same time by different astronomers), but in recent years, most new comets are discovered by automated telescopes, or arrays of telescopes, that monitor the sky, like ISON, NEOWISE, PANSTARRS, and ATLAS. Because many comets can have the same common name, astronomers use a more specific code assembled from the year and order of discovery.

As the comet continues toward the sun, the heat increases further and more melting occurs, until some of the material set free is swept back by the rapidly moving charged particles of the solar wind, forming a tail. Pushed by the solar wind, not the comet’s forward motion, the tail always fans out on the side opposite the sun—behind the nucleus as the comet approaches the sun, in front of the comet as it recedes.

Despite accelerating throughout its entire inbound journey, a comet will never move so fast that we’re able to perceive its motion at any given moment. Rather, just like planets and our moon, a comet’s motion relative to the background stars will only be noticeable when viewed from one night to another. And like virtually every other object orbiting the sun, a comet doesn’t create its own light. Rather, the glow we see from the coma and tail is reflected sunlight. The brilliance of its display is determined by the volume and composition of the material freed and swept back by the sun, as well as the comet’s proximity to Earth. The color reflected by a comet’s tail varies somewhat depending on its molecular makeup, but usually appears as some shade of yellow-white.

In addition to the dust tail, some comets exhibit an ion tail that forms when molecules shed by the comet’s nucleus are stripped of electrons by the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Being lighter than dust molecules, these ions are whisked straight back by the solar wind. Instead of fanning out like the dust tail, these gas ions form a narrow tail that points directly away from the sun. Also unlike the dust tail that shines by reflected light, the ion tail shines by fluorescence, taking on a blue color courtesy of the predominant CO (carbon monoxide) ion.

One significant unknown upon discovery of a new comet is whether it will survive its encounter with the sun at all. While comets that pass close to the sun are more likely to shed large volumes of ice and dust, many sun-grazing comets approach so close that they’re overwhelmed by the sun’s heat and completely disintegrate.

With millions of comets in our Solar System, it would be easy to wonder why they’re not a regular part of our night sky. Actually, Earth is visited by many comets each year, though most are so small, and/or have made so many trips around the sun that they no longer have enough material to put on much of a show. And many comets never get close enough to the sun to be profoundly affected by its heat, or close enough to Earth to shine brightly here.

Despite all the things that can go wrong, every once in a while, all the stars align (so to speak), and the heavens assuage the disappointment of prior underachievers with a brilliant comet. Early one morning in 1970, my dad woke me and we went out in our yard to see Comet Bennett. This was my first comet, a sight I’ll never forget. I was disappointed by the faint smudges of Comet Kohoutek in 1973 (a complete flop compared to its advance billing), and Halley’s Comet in 1986 (just bad orbital luck for Earthlings). Comet Hale-Bopp in 1996 and 1997 was wonderful, while Comet ISON in 2012 disintegrated before it could deliver on its hype.

In 2013 Comet PANSTARRS didn’t put on much of a naked-eye display, but on its day of perihelion, I had the extreme good fortune to be atop Haleakala on Maui, virtually in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. Even though I couldn’t see the it, using a thin crescent moon I knew to be just 3 degrees from the comet to guide me, I was able to photograph PANSTARRS and the moon together. Then, in the dismal pandemic summer of 2020, Comet NEOWISE surprised us all to put on a beautiful show. I made two trips to Yosemite to photograph it, then was able to photograph it one last time at the Grand Canyon shortly before it faded from sight.

October 2024 promised the potential for two spectacular comets, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS (C/2023 A3) in the first half of the month, and Comet ATLAS (C/2024 S1) at the end of the month. Alas, though this second comet had the potential to be much brighter, it pulled an Icarus and flew too close to the sun (RIP). But Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was another story, brightening beyond expectations.

I shared the story of my trip to photograph Tsuchinshan–ATLAS in my October 16 I’m Not Crazy, I Swear… blog post, but have a couple of things to add about this image. First is how important it is to not get so locked into one great composition that you neglect capturing variety. I captured this wider composition before the image I shared a couple of weeks ago, and was pretty thrilled with it—thrilled enough to consider the night a great success. But I’m so glad that I changed lenses and got the tighter vertical composition shortly before the comet’s head dropped out of sight.

And second is the clearly visible anti-tail that was lost in thin haze near the peaks in my other image. An anti-tail is a faint, post-perihelion spike pointing toward the sun in some comets, caused when larger particles from the coma, too big to be pushed by the solar wind, are left behind. It’s only visible from Earth when we pass through the comet’s orbital plane. Pretty cool.

When will the next great comet arrive? No one knows, but whenever that is, I hope I’ve kindled enough interest that you make an effort to view it. But if you plan to chase comets, either to photograph or simply view, don’t forget the wisdom of astronomer and comet expert, David Levy: “Comets are like cats: they have tails, and do precisely what they want.”

Join me in my Eastern Sierra photo workshop

More Gifts From Heaven

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

I’m Not Crazy, I Swear…

Posted on October 16, 2024

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and Mt. Whitney, Alabama Hills, California

Sony α1

Sony 100-400 GM

5 seconds

f/5.6

ISO 3200

Crazy is as crazy does

In college, my best friend and I drove from San Francisco to San Diego so he could attend a dental appointment he’d scheduled before his recent move back to the Bay Area. We drove all night, 10 hours, arriving at 7:55 a.m. for his 8:00 a.m. appointment (more luck than impeccable timing). I dozed in the car while he went in; he was out in less than an hour, and we drove straight home. I remember very little of the trip, except that each of us got a speeding ticket for our troubles. Every time I’ve told that story, I’ve dismissed it with a chuckle as the foolishness of youth. Now I’m not so sure that youth had much to do with it at all.

I’m having second thoughts on the whole foolishness of youth thing because on Monday, my (non-photographer) wife and I drove nearly 8 hours to Lone Pine so I could photograph Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS setting behind Mt. Whitney. We arrived at my chosen location in the Alabama Hills about 15 minutes after the 6:20 sunset, then waited impatiently for the sky to darken enough for the comet to appear. I started photographing at around 7:00, and was done when the comet’s head dropped below Mt. Whitney at 7:30. After spending the night in Lone Pine, we left for home first thing the next morning, pulling into the garage just as the sun set. For those who don’t want to do the math, that’s 16 hours on the road for 30 minutes of photography.

In my defense, for this trip I had the good sense (and financial wherewithal) to get a room in Lone Pine Monday night, and didn’t get pulled over once. That this might have been a crazy idea never occurred to me until I was back at the hotel, and that was only in the context of how the story might sound to others—in my mind this trip was worth every mile, and I have the pictures to prove it.

I say that fully aware that my comet pictures will no doubt be lost in the flood of other Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS images we’ll see over the next few weeks, many no doubt far more spectacular than mine. My excitement with the fruits of this trip is entirely personal, and to say I’m thrilled to have witnessed and photographed another comet would be an understatement—especially in light of last month’s Image of the Month e-mail citing comets as one of the three most beautiful celestial subjects I’ve ever witnessed. And of those three, comets feel the most personal to me.

Let me explain

When I was ten, my best friend Rob and I spent most of our daylight hours preparing for our spy careers—crafting and trading coded messages, surreptitiously monitoring classmates, and identifying “secret passages” that would allow us to navigate our neighborhood without being observed. But after dark our attention turned skyward. That’s when we’d set up my telescope (a castoff generously gifted by an astronomer friend from my dad’s Kiwanis Club) on Rob’s front lawn (his house had a better view of the sky than mine) to scan the heavens hoping that we might discover something: a comet, quasar, supernova, black hole, UFO—it didn’t really matter. And repeated failures didn’t deter us.

Nevertheless, our celestial discoveries, while not Earth-changing, were personally significant. Through that telescope we saw Jupiter’s moons, Saturn’s rings, and the changing phases of Venus. We also learned to appreciate the vastness of the universe with the observation that, despite their immense size, stars never appeared larger than a pinpoint, no matter how much magnification we threw at them.

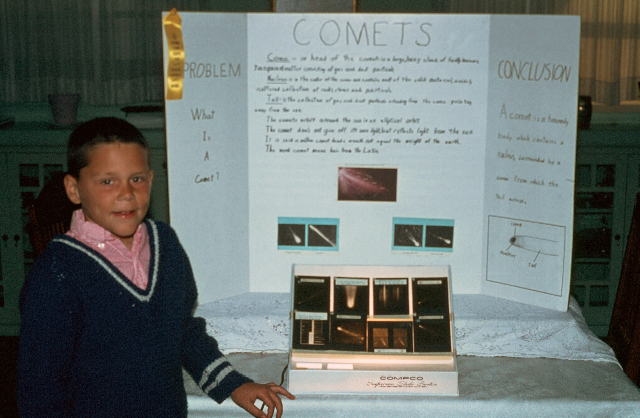

To better understand what we saw, Rob and I turned to illustrated astronomy books. Pictures of planets, galaxies, and nebula amazed us, but we were particularly drawn to the comets: Arend-Roland, Ikeya–Seki, and of course the patriarch of comets, Halley’s Comet (which we learned was scheduled to return in 1986, an impossible wait that might as well have been infinity). With their glowing comas and sweeping tails, it was difficult to imagine that anything that beautiful could be real. When it came time to choose a subject for the annual California Science Fair, comets were an easy choice. And while we didn’t set the world on fire with our project presentation, Rob and I were awarded a ribbon of some color (it wasn’t blue), good enough to land us a spot in the San Joaquin County Fair. (Edit: Uncovering the picture, I see now that our ribbon was yellow.)

Here I am with the fifth grade science project that started it all. (This is only half of the creative team—somewhere there’s a picture that includes Rob.)

The next milestone in my comet obsession occurred a few years later, after my family had moved to Berkeley and baseball had taken over my life. One chilly winter morning my dad woke me and urged me outside to view what I now know was Comet Bennett. Mesmerized, my smoldering comet interest flamed instantly, expanding to include all things astronomy. It stayed with me through high school (when I wasn’t playing baseball), to the point that I actually entered college with an astronomy major that I stuck with for several semesters, until the (unavoidable) quantification of the concepts I loved sapped the joy from me.

While I went on to pursue other things, my affinity for astronomy continued, and comets in particular remained special. Of course with affection comes disappointment: In 1973 Kohoutek fizzled spectacularly, a failure that somewhat prepared me for Halley’s anticlimax in 1986.

By the time Halley’s arrived, word had come down that it was poorly positioned for its typical display (“the worst viewing conditions in 2,000 years”), making it barely visible this time around, but I can’t wait until 2061! (No really—I can’t wait that long. Literally.) Nevertheless, venturing far from the city lights one moonless January night, I found great pleasure locating without aid (after much effort), Halley’s faint smudge in Aquarius.

After many years with no naked-eye comets of note, 1996 arrived with the promise of two great comets. While cautiously optimistic, Kohoutek’s scars prevented me from getting sucked in by the media frenzy. So imagine my excitement when, in early 1996, Comet Hyakutake briefly approached the brightness of Saturn, with a tail stretching more than twenty degrees (forty times the apparent width of a full moon).

But as beautiful as it was, Hyakutake proved to be a mere warm-up for Comet Hale-Bopp, which became visible to the naked eye in mid-1996 and remained visible until December 1997—an unprecedented eighteen months. By spring of 1997 Hale-Bopp had become brighter than Sirius (the brightest star in the sky), its tail approaching 50 degrees. I was in comet heaven. But alas, family and career had preempted my photography pursuits and I didn’t photograph Hale-Bopp.

Comet opportunities again quieted after Hale-Bopp. Then, in early 2007, Comet McNaught caught everyone off-guard, intensifying unexpectedly to briefly outshine Sirius, trailing a thirty-five degree, fan-shaped tail. McNaught put on a much better show in the Southern Hemisphere; in the Northern Hemisphere, because of its proximity in the sky to the sun, it provided a very small window of visibility, and was easily lost in the bright twilight. This, along with its sudden brightening, prevented McNaught from becoming the media event Hale-Bopp was. I only found out about it by accident, on the last day it would be easily visible in the Northern Hemisphere. By then digital capture had rekindled my photography interest (understatement), so despite virtually no time to prepare, I grabbed my camera and headed to the foothills east of Sacramento, where I managed to capture the McNaught image I share in the gallery below—my first successful comet capture.

Following McNaught, I vowed not to be caught off guard by a comet again. After enduring the frustration of promising (over-hyped?) comets disintegrated by the sun (you broke my heart, Comet ISON), and seeing others’ images of spectacular Southern Hemisphere-only comets (I’m looking at you, Comet Lovejoy), my heart jumped when I came across a website proclaiming the approach of Comet PANSTARRS (a.k.a, C/2011 L4 in less glamorous astro-nerd parlance), discovered not by an individual, but by the Pan-STARRS automated telescope array atop Haleakala on Maui.

Researching further, I learned that PANSTARRS could (fingers crossed) hang low in the western sky at magnitudes brighter than Saturn, for about a week right around its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) in March 2013, remaining visible as it rises but dims over the following few weeks. Checking my calendar to see if I had any conflicts that week, I realized I’d be on Maui for my workshop during PANSTARRS’ perihelion! Turns out my first viewing of PANSTARRS was atop Haleakala, almost literally in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. I also got to photograph a rapidly fading PANSTARRS above Grand Canyon on its way back to the farthest reaches of the Solar System.

Then, in 2020, came Comet NEOWISE to brighten our pandemic summer. I was able to make two trips to Yosemite and another to Grand Canyon to photograph NEOWISE (the Yosemite trips were for NEOWISE only).

One more time

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS has been on my radar for at least a year, but not something I monitored closely until September, when it became clear that it was brightening as, or better than, expected. By the end of September I knew that the best Northern Hemisphere views of Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would be in mid-October, but since I was already in the Alabama Hills at the end of September, just a couple of days after the comet’s perihelion, I went out to look for it in the pre-sunrise eastern sky (opposite the gorgeous Sierra view to the west). No luck, but that morning only solidified my resolve to give it another shot when it brightened and returned to the post-sunset sky.

At that point I had no detailed plan, and hadn’t even plotted its location in the sky beyond knowing it would be a little above the western horizon shortly after sunset in mid-October. My criteria were a nice west-facing view, distant enough to permit me to use a moderate telephoto lens. After ruling out the California coast (no good telephoto subjects) and Yosemite Valley (no good west-facing views), I soon realized I’d be returning to the east side of the High Sierra.

At that point I started working on more precise coordinates and immediately eliminated my first (and closest) candidate, Olmsted Point, because the setting comet didn’t align with Half Dome. My next choice was Minaret Vista (near Mammoth), a spectacular view of the jagged Minaret range and nearby Mt. Ritter and Mt. Banner. This was a little more promising—the alignment wasn’t perfect, but it was workable. Then I looked at the Alabama Hills and Mt. Whitney and knew instantly I’d be reprising the long drive back down 395 to Lone Pine.

Though its intrinsic magnitude faded each day after its September 27 perihelion, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS’s apparent magnitude (visible brightness viewed from Earth) continued to increase until its closest approach to Earth on October 12. While its magnitude would never be greater than it was on October 12, the comet was still too close to the sun to stand out against sunset’s vestigial glow. But each night it climbed in the sky, a few degrees farther from the sun, toward darker sky.

Though Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would continue rising into increasingly dark skies through the rest of October, and each night would offer a longer viewing window than the prior night, I chose October 14 as the best combination of overall brightness and dark sky. An added bonus for my aspirations to photograph the comet with Mt. Whitney and the Sierra Crest would be the 90% waxing gibbous moon rising behind me, already high enough by sunset to nicely illuminate the peaks after dark, but still far enough away not to significantly wash out the sky surrounding the comet.

At my chosen spot, I set up two tripods and cameras, one armed with my Sony a7RV and 24-105 lens, the other with my Sony a1 and 100-400 lens. I selected that first location because it put the comet almost directly above Mt. Whitney, 16 degrees above the horizon, at 7 p.m. But since the Sierra crest rises about 10 degrees above the horizon when viewed from the Alabama Hills, I knew going in that the comet’s head would slip behind the mountains at 7:30, slamming shut my window of opportunity after only 30 minutes.

When it first appeared, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was high enough that I mostly used my 24-105 lens. But as it dropped and moved slightly north (to the right), away from Whitney, we hopped in the car and raced about a mile south, to the location I’d chosen knowing that Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would align perfectly with Whitney as it dropped below the peaks. Most of my images from this location were captured with my 100-400 lens.

I manually focused on the comet’s head, or on a nearby relatively bright star, then checked my focus after each image. The scene continued darkening as I shot, and to avoid too much star motion I increased my ISO rather than extending my shutter speed.

As I photographed, I could barely contain my excitement at the image previews on my cameras’ LCD screens. Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and its long tail were clearly visible to my eyes, but the cameras’ ability to accumulate light made it much brighter than what we saw. The image I share today is one of my final images of the night. Even with a shutter speed of only 5 seconds, at a focal length of right around 200mm, if you look closely you’ll still see a little star motion.

My giddiness persisted on the drive back to Lone Pine and into our very nice (and hard earned) dinner. When our server expressed interest in the comet, I went out to the car and grabbed my camera to share my images with her. Whether or not the enthusiasm she showed was genuine, she received a generous tip for indulging me. And even though I usually wait until I’m home to process my images on my large monitor, I couldn’t help staying up well past lights-out to process this one image, just to reassure myself that I hadn’t messed something up (focus is always my biggest concern during a night shoot).

And finally…

FYI, neither Rob nor I became spies, but we have stayed in touch over the years. In fact, the original plan was for him to join me on this adventure, but circumstances interfered and he had to stay home. But we still have hopes for the next comet, which could be years away, or as soon as late this month….

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

My Comet History

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Channeling the Donner Party

Posted on July 18, 2024

Star Spangled Night, Milky Way and Tasman Lake, New Zealand

Sony a7R V

Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM

ISO 4000

f/1.8

20 seconds

Landscape photographers know suffering. With no control over the weather and light, we’re often forced to sacrifice comfort, sometimes even safety, in pursuit of our subjects. Cold, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, hunger—it all goes with the territory. But in the long run the successes, though never guaranteed, far outweigh the sacrifices.

So, when my wife and I scaled the short but steep trail (336 stairs—I counted) to the Tasman Lake overlook in New Zealand earlier this month, we knew it would be cold, and found out quickly that the route was treacherously icy as well. But we persevered and were rewarded with a lake view beneath the southern night sky that was almost beyond comprehension for our Northern Hemisphere brains.

Did I mention the cold? When I’m taking pictures, though I’m very much aware of the temperature, no matter how extreme, it never bothers me. For anyone with me who isn’t shooting? Not so much. But Sonya braved the frigid temps for 30 minutes—long enough to appreciate the majesty of the moment, and for me to get some nice pictures. Mission accomplished.

One of the things about planning a photo shoot in difficult conditions is anticipation and planning—not just for the shoot itself, but for all the other factors supporting it. In addition to the knowledge that the Milky Way would indeed be shining above the lake, and the moon wouldn’t be present to wash out the essential darkness, we also anticipated the possibility of an icy trail and carried a pair of Yaktrax for improved footing, made sure our lights were in working order, and had all the appropriate cold weather gear. And knowing that afternoon that we’d be driving into Aoraki / Mt. Cook National Park and possibly staying well past dark, I had the foresight (patting myself on the back) to check into our hotel in Twizel and make arrangements for dinner before embarking on our adventure.

Calling Twizel a sleepy town would be an understatement. Because our hotel locks the registration area and sends the staff home at 8:00 p.m., and most restaurants in town also close their doors at 8:00, at hotel check-in I inquired about a place in town to eat after 8:00. The woman at the front desk sent us to (raved about, in fact) a restaurant nearby. But not wanting to take her word that it would be open after 8:00, we drove over to talk to someone at the restaurant in person. When I explained to Carol, the nice lady who greeted us at the restaurant, that I wasn’t sure what time we’d be there, she said she’d just put us down for between 8:00 and 9:00. Great!

We were already getting hungry by the time we drove into the park and started our hike, but sucked it up like good photographers (well one of us at least—the other just sucked it up like a good human with a crazy partner). After our successful ascent and stay at the top, our prime emphasis on the descent was not falling on our butts, but rattling around the back of our minds was our extreme cold and hunger, and (especially) the relief waiting for us back in Twizel.

Back in town we beelined to the restaurant. Having checked the menu in advance, our mouths already watered in anticipation. It was still relatively full, but everyone was in the bar area watching the All Blacks vs. England rugby game (rugby is a religion in New Zealand, and the All Blacks are the deity of choice). There was no sign of Carol, any hostess or server, so I approached the bar and told the bartender we have a dinner reservation. He just stared at me like I’d asked where I could park my camel, finally saying with an implicit duh, “We stopped serving dinner at 8:00.” Dropping Carol’s name was met with a blank stare and a shrug. When I asked where else we might find dinner after 8:00 p.m., he just chuckled and said, “This is Twizel.”

By now it was after 8:45 and very clear that pleading with the bartender would be a waste of time, so we zipped over to town centre hoping to find something open. The only place with any sign of life was the local pub, so we parked and rushed in. Everyone here was watching the rugby game too, and try as we might, we couldn’t get enough of anyone’s attention to ask about dinner. Fortunately (or so it seemed), about then the game ended (All Blacks 16 — England 15) and the rugby zombies snapped out of their trances.

At least this time when we asked about dinner we got a little sympathy, but still no dinner. Walking back out into the cold and suddenly desperate, we remembered a gas station as we entered town—maybe we could at least find snacks there? Then we noticed a liquor store next door to the pub, a potential snack oasis in a frozen desert? Not so much. As we approached the entrance, a woman came out the front door and told us they’d just closed.

Turns out the gas station was fully automated, with no minimart, unlike pretty much every gas station in the US. So we limped back to the hotel, hoping maybe to find vending machines that would sustain us until breakfast. But with the lobby area locked tight, we had to enter through a side door that only provided access to the rooms, but none of the hotel’s other (meager) amenities.

By then we were so hungry we’d temporarily forgotten how cold we were. That is, until we turned the key in our door and walked into what surely must be a cryogenic chamber with beds. We were already accustomed to the unheated hotel hallways with temperatures that rival the temps outside (you can see your breath in a New Zealand hotel hallway in winter), but this was an entirely new level of cold. Before doing anything else, I went searching for the heater and finally found mounted to the wall a box with vents and a couple of knobs, about the size of a toaster. Surely this couldn’t be the heater?

It was in fact the heater. A heater, it turns out, that also doubles as a white noise machine. Genius! So we cranked it, keeping our outdoor clothes on while unpacking and rummaging for scraps of food in our luggage. Eventually Sonya struck pay dirt, excavating two pieces of hard candy from the bottom of her purse—dinner!

By 10:00 p.m. it had become pretty clear that the heater, despite achieving impressive decibel levels, was never going to generate enough warmth to make the room comfortable, and decided our best defense would be bed. While this did nothing for the hunger, perhaps sleep would mitigate our discomfort.

It’s amazing what being awake in a dark room does to the mind. Freezing cold, starving (okay, perhaps a bit of hyperbole but you get the idea), my thoughts kept drifting to the Donner Party. I discovered new empathy in their plight, but only the knowledge that Sonya is mostly vegetarian and doesn’t eat red meat allowed me to eventually drift off to sleep with both eyes closed.

Somehow, we survived the night.

(I should add that this is the only bad hotel experience I’ve ever had in New Zealand. Despite the chilly hallways, and bafflingly flaccid bacon, I truly love the hotels there.)

A few words about this image

In my prior blog post I shared the details of this night above Tasman Lake. But before checking out, I’d like to add a thought or two.

Most of my Milky Way shoots skew heavily to a vertical orientation that maximizes the amount of Milky Way in my frame. Between the wall of peaks stretching northward, and the Magellanic Clouds high in the southern sky, if ever a scene were to break me of this habit, it’s this view of Tasman Lake.

So this night I made a conscious effort to emphasize horizontal orientation, and the image I shared last week reflects that choice. But I’ve learned to never leave a beautiful scene, night or day, without giving myself both horizontal and vertical options.

Sometimes as soon as I reorient and put my eye to the viewfinder I’ll see something I missed; other times, it’s not until further scrutiny with the benefit of my large monitor at home, that I’m surprised to find I actually prefer the less obvious orientation.

So, despite my plan to emphasize horizontal frames this evening, I made sure I didn’t leave without some verticals as well. In this case, since I’ve photographed here before, I didn’t find anything especially surprising. But I did try something new, entirely ignoring the lakeshore and small pool on the rocks directly beneath me, including only enough lake to feature a couple of icebergs. This minimal foreground allowed the maximum Milky Way. (Which, at 14mm, turned out to be quite a bit of Milky Way.)

And as I’ve said before, the color of the lake in this image is real, though at night there isn’t enough light to see it. This ability to reveal realities lost to human vision is probably my favorite thing about photography.

Join Don Smith and me for next year’s New Zealand adventure

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

The Joy of Suffering

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Humor, New Zealand, Photography, Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM, Sony a7R V, stars, Tasman Lake Tagged: astrophotography, Milky Way, nature photography, New Zealand, stars, Tasman Lake

New Zealand After Dark

Posted on June 19, 2024

Dark Night, Milky Way and Tasman Lake, New Zealand

Sony a7S II

Sony 12 – 24 f/4 G

ISO 10,000

f/4

30 seconds

This week I have New Zealand on my mind. In preparation for the New Zealand Winter photo workshop that begins next week, I started going through unprocessed images from prior New Zealand visits. I was actually looking for something else when I stumbled upon this Milky Way image from the 2019 trip, when Don Smith and I guided a group of Sony influencers around the South Island. I’d already processed a virtually identical composition of this scene back then, but since my Milky Way processing has evolved (improved), I decided to give it another shot.

Day or night, I love this Tasman Lake scene in particular because it so beautifully captures what I love most about New Zealand. We only do this workshop in winter, which of course leads to the inevitable question: “Why?” The simple answer is that the modest sprinkling of tourists, consistently interesting skies, and snowy peaks I love so much, are only possible in winter. I could go on and on with my answer, but since a picture is worth a thousand words, I’ll just save you some time and give you six-thousand words worth of examples. (You’re welcome.)

But even once I convince skeptics that winter in New Zealand is in fact quite beautiful, I’m usually hit with a follow-up: “But isn’t it cold?” Sure it’s cold, but by most people’s expectations of winter, New Zealand’s South Island is actually quite mild—with average highs in the 40s and 50s, and lows in the 30s, it’s similar to winter in Northern California and Oregon. I would venture that there’s not a single person reading this who doesn’t already have in their closet enough winter warmth to ensure cozy comfort in a New Zealand winter. Also like Northern California and Oregon, in winter New Zealand’s South Island gets rain and fog in the lowlands, and snow in the mountains, conditions I find so much better for photography (and for just plain being outside) than the sweltering blank-sky California summers I left back home.

All that said, for me the strongest argument for winter in New Zealand is Southern Hemisphere’s night sky. Inherently pristine air and minimal light pollution makes New Zealand is an astrophotographer’s paradise any season. But winter is when the Milky Way’s brilliant core shines in the east after sunset, already much higher above the horizon than my Northern Hemisphere eyes are accustomed to. The galactic core remains visible all night, ascending further and slowly rotating westward, before finally fading on the other side of the sky in the pre-sunrise twilight. That means more than 12 hours of quality Milky Way time, and the ability to place it above landscapes facing east, north, or west, by simply choosing the time of night you photograph it. And joining the celestial show are the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds—satellite galaxies of our Milky Way, only visible in the Southern Hemisphere.

Benefiting from our years of experience on the South Island, Don and I have identified many very nice locations for photographing the Milky Way, but our two favorites feature the galactic core above glacial lakes that are bounded by snowy peaks. One of these is on the shore Lake Wakatipu near Queenstown; the other is a vista above Tasman Lake in Mt. Cook / Aoraki National Park. This week’s image, from the 2019 trip, is of the Tasman Lake scene.

From the very first time my eyes feasted on it, I marveled at what a spectacular place the Tasman Lake view would be to photograph the Milky Way. In 2019, Don and I were especially pleased to be guiding this group of young photographers who were as excited about photographing the Milky Way as we were, so this shoot was in our plan since before the workshop started.

The sky this evening was crystal clear, but as the sky darkened, I found myself still down at the foot of the lake (just out of the frame on the far right), where I’d photographed sunset with most of the group. The majority decided to stay put for the Milky Way shoot, and while I couldn’t deny that this spot would likely be no less spectacular, I couldn’t pass the opportunity at the elevated lake view that had been on my radar for so long. I also thought the Milky Way would align better with the most prominent peaks from this vantage point. So I scrambled back up the boulders to the trail and race-walked more than a mile, then scaled more than 300 stairs in near darkness, to get in position.

I expected to find the few who weren’t down at the lakeside sunset spot (this group always scattered) would already be up here, but I arrived to find the view empty. While I was happy to eventually have the company of a couple of others, the utter solitude I enjoyed for the first 30 minutes felt downright spiritual.

Going with my dedicated night camera, the Sony a7S II, I started with my default night lens at the time, the Sony 24mm f/1.4. But the scene was so expansive, I quickly switched to my Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM for a wider view. While that did the job for a while, it wasn’t long before I found myself wanting an even bigger view, so I reached for my Sony 12-24 f/4 G lens. Because light capture is the single most important factor in a Milky Way image, in general I find f/4 too slow. (Today I’d use my 14mm f/1.8 or 12-24 f/2.8, but back then those lenses were still at least a year away.) But really wanting the widest possible view, I rationalized that since the a7S II can handle 10,000 ISO without any problem, and the star motion of a 30-second exposure at 12mm would be minimal, and just went for it. Mitigating the f/4 exposure problems was the fact that the best parts of the scene’s foreground, the snow and water, were highly reflective, while the dark rock wasn’t really essential to the scene.

The result as processed in 2019, while noisier than ideal, was still usable. But as time passes, I’ve become less and less thrilled with many of my old Milky Way processing choices—that image was no exception. Since I’ve been pretty thrilled with the results reprocessing old Milky Way images with Lightroom’s latest noise reduction tool, I thought this might be a great time to reprocess this old scene to see if I could do it better.

For no reason in particular, I chose different image to process, but the compositions are nearly identical. As expected, the new Lightroom noise reduction did a much better job minimizing the inevitable noise that comes at 10,000 ISO, so I was already ahead of the game. The only other major processing improvement I made was the color of the sky, which, as my night sky processing evolves, I’m making much less blue.

Because no one knows what color the night sky supposed to be when given the amount of exposure necessary bring out foreground detail, I’ve always believed that the color of the sky in a Milky Way image is the photographer’s creative choice. I mean, scientists might be able to tell you what color it should be (there’s a very strong case for green), but to me the bottom line is image credibility (and green just won’t do it).

Whatever night sky color I’ve ended up with has entirely a function of the color temperature I choose when I process my raw file in Lightroom—no artificially changing the hue, saturation, or in any other way plugging in some artificial color. Since I do think the foreground (non-sky) of a night image looks more night-like (I don’t want a night image that looks like daylight with stars) with the bluish tint I get when the color temperature is cooled to somewhere in the 3000-4000 degrees range (photographers will know what I’m talking about—non-photographers will just need to take my word), for years I cooled the entire image that way—hence the blue night skies. But Lightroom now makes it super easy to process the sky and foreground separately and seamlessly, so I no longer cool my night skies nearly as much as before (or at all). Now my night skies tend to be much closer to black, trending almost imperceptibly to the purple side of blue (avoiding the cyan side).

Oh, and the color of Tasman Lake you see in this image is real, I swear—the color of the South Island’s glacial lakes is another reason to love this country, but that’s a story for another day.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

This year’s New Zealand workshop is full, but Don and I will do it again next year.

New Zealand After Dark

Category: New Zealand, reflection, Sony 12-24 f4 G, Sony a7SIII, Tasman Lake Tagged: astrophotography, Milky Way, nature photography, New Zealand, reflection, stars, Tasman Lake

A Dose of Perspective

Posted on December 6, 2023

Celestial Reflection, Milky Way Over the Colorado River, Grand Canyon

Sony a7SIII

Sony 20mm f/1.8 G

ISO 12800

f/1.8

30 seconds

Nothing in my life delivers a more potent dose of perspective than viewing the world from the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Days are spent at the mercy of the Colorado River, alternately drifting and hurtling beneath mile-high rock layers that reveal more than a billion years of Earth story. And when the sun goes down, the ceiling transforms into a cosmological light show, each stellar pinpoint representing a different instant in our galaxy’s past.

I’ve done this raft trip eight times now—long enough to know that when I stop doing it, the night sky is what I’ll miss most. To ensure the darkest skies (and the most stars), each trip is timed around the lunar minimum when the moon’s only appearance is a thin crescent is shortly before sunrise or after sunset. For most of my rafters, these are the darkest skies they’ll ever see—so dark that the Milky Way actually casts a faint shadow.

While cloudless nights down here always deliver a seemingly impossible display of stars, viewing the glowing core of our Milky Way galaxy is never assured. In the Northern Hemisphere, even when the galactic core reaches its highest point, it’s still relatively low in the southern sky. So, given the Grand Canyon’s general east/west orientation (high walls north and south), the best Milky Way views are usually blocked by the canyon’s towering walls. But these trips spend the first two nights in the north/south-trending Marble Canyon stretch of Grand Canyon, where we can enjoy open views of the north and south sky. And even after the canyon’s westward bend just downstream from the Little Colorado River confluence, a few fortuitous twists in the river open more nice southern views.

Campsites along the Colorado River are all first-come, first-served—if you set your sights on a Milky Way spot and arrive to find it occupied, there’s no option but to continue downstream. Over the years my (incomparable) guides and I have become pretty adept at identifying and (equally important) securing the best sites for Milky Way views—if the weather cooperates, we always score one or (usually) more quality Milky Way shoots.

One more Grand Canyon Milky Way obstacle I should mention is that even in the most favorable locations, the galactic core doesn’t rotate into the slot between the canyon walls until around 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning. Often rafters go to bed with every intention of rising to photograph it, but when the time comes to rise and shoot, their resolve has burrowed somewhere deep in the cozy folds of their sleeping bags. The best antidote for this is willpower, bolstered by bedtime preparation. To assist my rafters, I prescribe at the very least:

- Pick your campsite strategically, with the Milky Way in mind. (The first thing I do when we land is let everyone know where the Milky Way will appear.) That means either setting up your cot or tent with a good view of the southern sky, or at a place with easy access (in pitch darkness) to your desired shooting spot.

- Before going to bed, identify your composition, set up your camera, lens, and tripod, set your exposure (a relative constant that I’m able to help with), and focus at infinity.

- Have your camera ready atop the tripod and beside your cot (or outside your tent) when you go to bed. Some people just wake and shoot from their campsite (sometimes not even leaving their cot), but I usually prefer walking down to the river for the best possible foreground.

- Better still, if it can be done without risk of someone stumbling over it in the dark, leave the camera composed and focused at your predetermined shooting spot. But if this spot happens to be beside the river, check with the guides because the river level fluctuates on a known schedule (based on releases from Glen Canyon Dam timed for peak flow during peak electricity demand, and distance downstream).

I’ve learned that it isn’t practical to plan a group shoot for the wee hours of the morning, so I let people know when I plan to be up and where I’ll be, then let them decide whether to join me, choose their own time or place, or just stay in bed.

Regardless of the night’s Milky Way plan, I always forego the available but optional tent in favor of the unrivaled celestial ceiling. At home I’m a read-until-the-book-drops-to-my-chest guy, but down here I just lie flat on my back with my eyes locked heavenward, scanning for meteors, constellations, and satellites until my eyelids fail me. Here’s a sample of the mind-boggling thoughts that crowd my mind as I gaze:

- The light from every single pinpoint up there was created at a different time, and took many, sometimes thousands of, years to reach us—I really am peering back into the past.

- That streaking meteor was no larger than a pea and had probably been drifting around the solar system for millions, or billions, of years.

- Many of these stars host planets capable of hosting life.

- Our Milky Way galaxy is home to 10 times as many stars as there are people on Earth.

- For each star in the Milky Way, there are at least 20, and possibly as many as 200, galaxies in the Universe—many with trillions of stars.

Mind sufficiently boggled, I’ll eventually drift off to sleep (resistance is futile), but am fortunate that I don’t usually need to set an alarm to wake up—at bedtime I just tell myself what time I want to be up and trust my body’s clock. Then I psych myself into getting up by thinking I’m just going to fire off a dozen or so frames and then go back to bed. Of course I usually end up staying out much longer—always when there are others up and needing help, but often just because once I’m awake, the sky is just too beautiful to go back to sleep.

Rising for the galactic core’s arrival gives a good two or three hours of quality Milky Way time before the sky starts to brighten noticeably in the camera, sometime around 4:00 a.m. (the eyes don’t see the brightening for another half hour or so). I use all that dark time to work on a variety of compositions and exposure settings, sometimes moving around, but often staying put and just letting the Milky Way do the moving across the scene, from one side of the canyon to the other.

Since the “star” of the Grand Canyon night images is the sky, and vertical orientation gives me more of the vertically oriented Milky Way framed by the canyon’s vertical walls, my initial compositions are usually vertical. But the longer I do this, the more I’ve tried to lean into horizontal compositions as well, giving the canyon walls billing equal to the Milky Way.

Today I’m sharing a newly processed image from my 2021 raft trip—you can read the story of this night, and see a vertical version of the scene, here. This spot has become one of my favorite campsites because of the way, when the flow is just right, the water here spreads and pools at an extreme bend in the river. The reflection this night was spectacular, probably the best I’ve ever seen here, and (needless to say) I got very little sleep.

FYI

This image (like all of my images) is a single click (no compositing of multiple frames) with no artificial light added (no light painting or any other light besides stars and skylight). I was using my 20mm f/1.8 lens, which was wide enough, but I sure wish I’d have had the 14mm f/1.8 that was on order but didn’t arrive on time.

I had to skip the 2023 Grand Canyon raft trip, but am excited to be returning in May of 2024—and I just scheduled my 2025 trip.

Milky Way Favorites (one click—no blending)

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Colorado River, Grand Canyon, Milky Way, Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM, Sony a7SIII, stars Tagged: astrophotography, Grand Canyon, Milky Way, nature photogaphy, reflection, stars

That Time Elon Musk Photobombed My Workshop…

Posted on August 15, 2023

Milky Way and SpaceX Falcon 9, Wotan’s Throne, Grand Canyon

Sony a7R V

Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM

ISO 4000

f/1.8

25 seconds

Last week’s Grand Canyon Milky Way shoot almost didn’t happen, but by the time all was said and done, we ended up with far more than we’d bargained for.

My Grand Canyon monsoon workshops are ostensibly about photographing all of Grand Canyon’s unrivaled beauty, but ask anyone who signs up and they’ll tell you their number one goal is lightning. About 70 percent of my monsoon groups have what I consider lightning success: everyone in the group gets at least one nice lightning image. Of course that also means in 30 percent of my groups, not everyone gets lightning—I can prepare them, monitor the activity, and put us in the locations that maximizes our chances, if the lightning isn’t happening, there’s not much I can do. On the other hand, the clouds that bring lightning often wipe out the night sky, so the (generous) consolation prize for the clear-sky groups is the opportunity to photograph the Milky Way in the dark Grand Canyon sky.

After spending the first two days of this year’s second Grand Canyon workshop beneath wall-to-wall blue skies, all of us were excited about photographing the Milky Way on that second night. Though I was a little concerned about the wind during the Cape Royal sunset shoot, it wasn’t until walking over to my nearby Milky Way location in the darkening twilight (for a less obstructed view and better angle to our foreground subject, Wotan’s Throne), that I really started to fear our Milky Way shoot might not happen. I’d hoped that the more sheltered location would help, but the wind there was just as intense, blowing so hard that I wasn’t sure we’d be able to keep our cameras stable throughout the long exposures a Milky Way shoot requires.

Not only that, the views this spot offers are very exposed, with no railings above a precipitous vertical drop (there’s also room back from the edge for all who aren’t comfortable with heights, so no one is forced to stand on the edge). That meant, given the wind gusting to 40 MPH, in addition to camera stability concerns, I was more than a little concerned about someone straying too close to the edge and getting knocked off balance by a sudden gust. Yikes.

After pondering all this, I decided that we’d hang out a safe distance from the edge at least long enough for the darkening sky to reveal the Milky Way. Best case, the wind would die enough for us to photograph; worst case, we’d at least get to see the Milky Way, always a treat. (Okay, the real worst case would be someone stumbling over the cliff in the dark, but there was really no need for anyone to vacate their safe vantage point once we were established.)

As we waited, I realized that the gusty wind often slowed long enough that we might be able to time our captures between gusts and decided we may as well give the Milky Way a shot—when darkness was complete, we were open for business. With each person’s camera safely affixed to their tripod, Curt (the photographer assisting me) and I moved around to ensure that all had achieved reasonable focus, the right exposure settings, and a good composition. Thanks to our optional practice shoot at Grand Canyon Lodge (where the South Rim lights make for less than ideal Milky Way conditions) the prior night, the group got up to speed quickly.

With exposures in the 10 to 30 second range (double that if long exposure noise reduction is turned on), we had lots of time while waiting for each exposure to complete to simply appreciate skies darker than any of us get at home—for some, darker than they’d ever seen.

It truly is a joy to watch the stars pop out in a darkening sky. There’s Spica in Virgo, Arcturus in Bootes, Antares in Scorpius, plus a host of less prominent stars. Splitting the dark like sugar spilled in ink was our Milky Way galaxy’s luminous core. Two or three times a meteor flashed through the scene, perhaps a stray Perseid streaking from behind us, but most likely just a random piece of space dust.

But wait a minute… What’s that? As I mentally checked through all the familiar skymarks (I just made-up that word), something new caught my eye. Expanding in the southwest sky was a large diaphanous disk. We all saw it at about the same time, which told me that it had just appeared. My first thought, which I uttered out loud only half joking, was, “I hope it’s one of ours.”

Living in California my entire life means I’ve seen a few rocket launches—none that looked exactly like this, but similar enough that I was pretty confident that’s what we were seeing. I did a quick Google search and the first thing that popped up was a SpaceX Falcon 9 Starlink mission launching from Vandenberg Air Force Base on California’s Central Coast, nearly 500 miles away, at 8:57 that night. I checked my watch: 9:04 p.m.—mystery solved.

SpaceX was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk to further his dreams of space dominance. Propelled by reusable Falcon and (soon) Starship rockets, SpaceX crafts deliver both human and electronic payloads to space. Today the human payloads are primarily mega-rich tourists, but the eventual goal is to put humans on the Moon, Mars, and perhaps beyond.

A more practical current SpaceX implementation is the Starlink satellite system that blankets Earth and is capable of providing Internet service anywhere on the planet. I’ve used Starlink at a location where I’d previously had no Internet (the Grand Canyon North Rim, actually) and was absolutely blown away by the speed and reliability—not as fast as home, but certainly fast enough for reasonable use (I didn’t stream any movies, but I did stream shorter videos without problem). On the other hand, this year we tried Starlink on the North Rim and didn’t have a clear enough view through the trees to get a reliable signal—sometimes it worked, but mostly it didn’t.

Which is why SpaceX is still adding satellites. As of August 2023 4,500 Starlink satellites orbit roughly 200 – 350 miles above Earth’s surface. The launch we witnessed last Monday added another 15, with the ultimate goal being as many as 42,000!

I found a video of the launch and learned that 7 1/2 minutes after liftoff, a few seconds before I captured this image, the rocket propelling the satellites toward orbit was 175 miles above Earth’s surface, traveling over 10,000 MPH. But the the Falcon 9 rocket achieves this altitude and speed by using two stages—when the first one has exhausted its fuel, it steps aside and defers to stage two. After doing a little research I’m pretty sure what we witnessed was the beginning of the stage-1 rocket’s return to Earth—the second stage and its satellite payload were out of sight.

Five minutes earlier (2 1/2 minutes into the flight), it’s job done, stage 1 had shut down and separated from the moneymaking section of the rocket, turning control of the payload delivery to stage 2. At that point the rocket was about 50 miles above Earth, traveling about 4,700 MPH. As stage 2 took over, accelerating its payload of satellites even further heavenward, it rapidly outpaced the jettisoned first stage.

With nothing propelling stage 1 forward, Earth’s gravity became the only force acting on it, causing immediate deceleration. But with so much momentum and virtually no atmosphere to slow it further, the depleted stage 1 continued climbing for about 2 1/2 more minutes.

Without further intervention, stage 1 would have plummeted far out in the Pacific. But SpaceX wants to reuse it, so about 7 1/2 minutes into the flight, when it was about 42 miles above the ocean and traveling more than 4,800 MPH, stage one threw on the brakes with a 20-second entry burn timed to deliver it into the waiting “arms” (landing pad) of a SpaceX ship positioned in the east Pacific, west of Baja California. Bullseye (watch the video and be amazed).

I believe the glowing cloud my group and I witnessed was the exhaust from this entry burn, illuminated by the sun. The red streak is the rocket burn itself.

The opportunity to view this phenomenon is relatively rare. Because the exhaust cloud has no inherent luminance, it’s visible only when illuminated by sunlight. That means Earth-bound viewers must be beneath dark skies, and the exhaust plume must be high enough to still have a direct line of sight to the sun—in other words, night below, daylight above. Too far east and the plume would get no sunlight; too far west and it wouldn’t have been visible to anyone beneath a night sky. This convergence requires a twilight launch, cloudless skies, and a viewing position within a relatively small terrestrial zone just into the dark side of night’s advancing shadow.

I virtually never photograph anything manmade, but this was too cool to lose to silly personal rules. At this point, still completely ignorant of all I detailed above, I quickly adjusted my composition to include more of the glowing exhaust plume without losing the Milky Way and Wotan’s Throne. I just stuck with the exposure values I’d already been using. I got exactly one frame before the rocket and its cloud faded noticeably—I just hoped the image was sharp.

I come from the generation where space flight was celebrated, a time when the world stopped to watch every launch, splashdown, and space milestone. Teachers would wheel televisions into classrooms so we could all view together, and I still have vivid memories of watching Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon. But as amazing as this SpaceX launch was to view and photograph, and no matter how beneficial this technology is, I can’t help being more than a little concerned about what all this hardware in space is doing to our once pristine night sky.

When I was a kid gazing up at the night sky, spotting a satellite was a rare and thrilling event. But in this 25-second exposure I count at least 9 satellites of varying degrees of brightness—what’s our night sky experience going to be like when Starlink’s count reaches its 42,000 goal, and SpaceX’s inevitable competitors try to match them?

And if scientific exploration is important to you, consider that satellites have become the bane of optical astronomers’ existence. SpaceX has started applying a less reflective surface to its Starlink satellites, reducing their visibility by about 50% (better than nothing but still not great), but also increasing their surface temperatures, making them more problematic for infrared astronomy.

I don’t really have a solution for this conundrum, I just hope that moderation is applied to these technological advances, and that factors beyond the bottom line are considered as we dig deeper into space.

(And I still love this image.)

Join me at the Grand Canyon

To Infinity and Beyond

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Cape Royal, Grand Canyon, Milky Way, Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM, Sony a7R V, SpaceX Falcon 9, stars, Wotan's Throne Tagged: astrophotography, Elon Musk, Falcon 9, Grand Canyon, Milky Way, nature photography, SpaceX, stars, Wotan's Throne

Smart Luck

Posted on July 30, 2023

Milky Way and the Southern Alps, Mt. Cook / Aoraki National Park, New Zealand

Sony a7R V

Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM

ISO 12800

f/1.8

10 seconds

Once upon a time I posted a rainbow image on Facebook and someone commented that getting a shot like that is simply dumb luck. After having a good chuckle, I actually felt a little sad for the commenter. Since we all tend to make choices that validate our version of reality, imagine going through life with that philosophy.

No one can deny that photography has a significant luck component, but each of us chooses our relationship with the fickle whims of chance—I prefer to look for smart luck. Smart luck embraces Louis Pasteur’s conviction that chance favors the prepared mind. Ansel Adams was quite fond of repeating Pasteur’s quote, and later Galen Rowell as well as many other photographers have jumped on board. So while many may indeed feel lucky to have witnessed special moments in Nature, let’s not lose sight of our opportunities to create our own “luck.” Smart luck.

Some examples

As nature photographers, we must acknowledge the tremendous role chance plays in the conditions that rule the scenes we photograph, then do our best to maximize our odds for witnessing whatever special something Mother Nature might toss in our direction. A rainbow over the Safeway parking lot or the sewage treatment plant is still beautiful, but a rainbow above Yosemite Valley can ascend to a lifelong memory (not to mention a beautiful photograph).

I’ll never forget the time, while driving to Yosemite to meet new clients to plan the next day’s tour over dinner, I saw conditions that told me a rainbow was possible. When I met the clients at the cafeteria, I “suggested” (pleaded?) that we forget dinner and take a shot at a rainbow instead. Despite no guarantee of success, we raced our empty stomachs across Yosemite Valley, scaled some rocks behind Tunnel View, and sat in a downpour for about twenty minutes. Our reward? A double rainbow arcing across Yosemite Valley. Were we lucky? Absolutely. But it was no fluke that my clients and I were the only “lucky” ones out there that evening.

Before sunrise on a chilly May morning in 2011, my workshop group and I had the good fortune photograph a crescent moon splitting El Capitan and Half Dome before sunrise. Was this luck? I’ll give you one guess.

I suppose we were lucky that our alarms went off, and that the clouds stayed away that morning. But I knew at least a year in advance that a crescent moon would be rising at this less heralded Yosemite vista on this very morning, scheduled my spring workshop to include the date, then spent hours obsessively making sure I hadn’t made any mistakes.

I’d love to say that I sensed the potential for a rainbow over the Grand Canyon when I scheduled my 2016 Grand Canyon raft trip, then hustled my group down the river for three days to be in this very position to witness the moment. Sadly, I’m not quite that prescient. On the other hand, I did anticipate the potential for a rainbow at least an hour earlier, scouted our campsite to determine the best locations to photograph it, then called the rainbow’s arrival far enough in advance that everyone was able to grab their gear and be set up before its arrival.

Anticipating these special moments in nature doesn’t require any real gifts—just a basic understanding of the natural phenomena you’d like to photograph, and a little effort to match your anticipated natural event (a rainbow, a moonrise, the Milky Way, or whatever) with your location of choice.

But to decide that photographing nature’s most special moments is mostly about luck is to pretty much limit your rainbows to the Safeways and sewage treatment plants of your everyday world. I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve prepared for a special moment in nature, changed plans, lost sleep, driven many miles, skipped meals, and suffered in miserable conditions, all with nothing to show for my sacrifice. But just one success like a rainbow above Yosemite Valley or the Grand Canyon is more than enough compensation for a thousand miserable failures. And here’s another secret: no matter how miserable I am getting to and waiting for my goal event, whether it happens or not, I absolutely love the anticipation, the just sitting out there marinating in the thought that it might happen.

About this image

Don Smith and I didn’t choose New Zealand in June by accident. And it was no fluke that we were at this spot beneath the Southern Alps on a moonless night. June is when the Milky Way’s core rises highest in the night sky, and we knew exactly where to be when it came out this night. Well, we thought we knew exactly where to be…

Our New Zealand workshop group had had such a great Milky Way experience on the workshop’s first night, everyone wanted to do it again. But this year’s trip encounter more fog than we ever have, which brought us some nice daytime conditions but wasn’t particularly conducive to night photography. We finally got another chance on the workshop’s penultimate night, when the sky cleared at one of my favorite places for night photography. After a nice sunset shoot, we went to dinner (at a spectacular buffet) while waiting for the sky to darken, then headed back out.

But when we arrived at our predetermined location, a bridge over the Hooker River, we discovered that workers doing grading (I assume) on the riverbank just upstream had left a spotlight on outside their little shed, perhaps by mistake, or maybe to discourage thieves. Whatever the reason, it was so bright that it washed out the bottom half of everyone’s frame. No problem—we were familiar enough with the location that we were able to drive up the road a mile or so until we found a nice view where the light wasn’t a factor.

This far into the workshop everyone was fairly comfortable with their cameras, but the utter darkness out there added another layer of complication. Spreading out along the shoulder, we had to take care not to bump into tripods and each other, but once everyone established their positions and started finding compositions that worked, there wasn’t really any need to move around. At that point the job for Don and I is mostly to be a resource—help people with their compositions and focus (mostly just checking to ensure that it’s okay)—and just stay out of the way.

Since most of my compositions at the prior Milky Way shoot had been vertical, this night I opted for horizontal frames that included more mountains. With nothing special in the immediate foreground, I minimized it in my frame. I further deemphasized (darkened) the foreground with a faster shutter speed that had the added benefit of reducing star motion.