Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

In the Pink

Posted on February 14, 2026

Twilight Wedge and Setting Moon, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 G

1/5 second

F/16

ISO 100

The rewards of rising before the sun are many. For me, the opportunity to witness twilight’s soft, cool light slowly warmed by the approaching sun, to breathe in the cleanest air of the day, and to simply be alone with the purest sounds and smells of nature, are ample compensation for whatever chill and sleep deprivation I might experience. And on mornings when the sky is cloudless and the air especially pure, there might just be a bonus.

To collect that bonus, about 20 minutes before sunrise, look for parallel bands of vivid pink and steely blue hugging the horizon opposite the rising sun. Many photographers, myself included, call this early display the “twilight wedge,” but it has other similarly non-scientific names. Closer to the horizon, the dark blue band is actually Earth’s shadow—the final section of sky not receiving any direct light from the soon to appear sun; just above, the pink band is the the day’s first rays of direct sunlight. It’s pink because the sun is just far enough below the eastern horizon that the only its longest, red wavelengths manage to battle through the atmosphere all the way to the other side of the sky. The cleaner the air, the more vivid the twilight wedge’s color. (This color is also possible after sunset, but by day’s end there are usually more color-robbing particles in the air, and Nature’s quiet is often disturbed so much by human activity that some of the magic is lost.) And when towering peaks soar far enough above the viewer’s vantage point that they jut into this pink twilight wedge band, we call it alpenglow.

I love finding beautiful scenes to go with the gorgeous pre-sunrise sky opposite the sun. Near the top of my list is the Alabama Hills, in the shadow of the highest Sierra Nevada peaks. The Alabama Hills are a disorganized jumble of massive, weathered boulders covering many square miles, making an ideal foregrounds for the assortment of serrated peaks looming to the west. A more perfect arrangement for nature photographers couldn’t be assembled—and, as if that’s not enough, the Alabama Hills are also among the best places on Earth to photograph alpenglow.

Of course all this is no secret, and the Alabama Hills has become one of the most popular photography spots in California. To improve my chances of capturing unique images here, I love adding the moon to my Alabama Hills / Sierra Crest scenes. (And when I say “add,” I mean the honorable, old-fashioned way, not with AI or other digital shenanigans.) For years, I’ve timed my Death Valley winter workshop to allow me to take my group to the Alabama Hills, just a 90 minute drive from Death Valley, for the workshop’s final sunset, followed by the moon setting behind the Sierra Crest at sunrise the final morning.

Of course, because there’s only one “best” day in each lunar cycle to photograph a full (-ish) moon setting behind the Sierra Crest, I have no wiggle room when scheduling this workshop—a day early, and the moon is gone before the landscape is light enough to photograph; a day late, and the sky is much too bright by the time the moon drops close to the mountains.

But even nailing the day doesn’t ensure success. Clouds are of course a concern, especially in winter. And each year the timing and position of the moon’s disappearance behind the crest is a little different. In January and early February (when I always schedule this workshop), viewed from my preferred location, the moon sets somewhere between Mt. Whitney and Mt. Williamson (California’s two highest peaks), usually closer to Williamson.

I like to get my groups out to the Alabama Hills about 30 minutes before we can start photographing the moon. The foreground will still be quite dark to our eyes, and the moon will at least 10 degrees above the crest, but I tell my students to start shooting as soon as we arrive.

Using a long exposure in a frame that doesn’t include the moon (the top of the frame is below the moon), captures much more (mostly shadowless) foreground detail than our eyes see, while juxtaposing the mountains’ light gray granite against a sky that’s darker than the peaks—a magnificently striking sight indeed, especially when there’s snow on the peaks. We’ll keep shooting versions of this until it’s time to include the moon in the festivities.

For any moon photography, the darker the sky, the better the moon stands out. But too early and it’s impossible to capture foreground detail without completely blowing out the moon. For me, the time to photograph any setting full moon starts about 20 minutes before sunrise—basically, as soon as the landscape has brightened enough foreground and lunar detail with one click. And if we’re especially lucky, when that time arrives, we’ll find the moon in the midst of a vivid pink twilight wedge.

This opportunity only lasts a few minutes, because as the sky brightens and the foreground exposure gets easier, the color fades and the essential contrast between the sky and moon decreases. The twilight wedge lasts less than 10 minutes, and is followed by slowly warming sky. By maybe five minutes after sunrise, the good color is long gone and the moon/sky contrast has decreased enough for me to put my camera away.

This year’s Alabama Hills moonset was especially nice. One of my favorite things about my Death Valley / Alabama Hills workshop is that we get two “ideal” (moon setting as the color and light are at their best) sunrise moonsets for the price of one. On our last day in Death Valley, from Zabriskie Point we photograph the moon setting behind Manly Beacon, one of Death Valley’s most striking and recognizable features. Because the mountains behind which the moon sets from Zabriskie rise only about 3 degrees above a flat horizon, this moonset happens much closer to the “official” (flat horizon) sunrise that’s universally used for any celestial rise and set. The next morning we’re in the Alabama Hills—even though the moon sets about an hour later than it did the day before, because the Sierra Crest towers about 10 degrees above the horizon when viewed from the Alabama Hills, the actual moonset we see happens at just about the same time as the prior day’s moonset.

Which is exactly things unfolded for this year’s workshop group. We followed up a beautiful Death Valley Zabriskie Point sunrise moonset, with a similarly outstanding Alabama Hills sunrise moonset the next morning. The vivid hues of the twilight wedge had just peaked when I clicked this image. To my eyes, this entire scene (except the moon), and especially the foreground, was much darker than this image shows. But my camera’s ridiculous dynamic range, combined with Lightroom’s masking that allows me to process the sky and foreground independently from each other, enabled me to expose the scene dark enough to capture essential lunar detail, yet remain confident I had enough recoverable detail in the foreground.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Alabama Hills Gallery

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra, full moon, Moon, Mt. Whitney, Photography, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V Tagged: Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra, full moon, moon, moonset, Mt. Whitney, nature photography

Open Mind and Open Eyes

Posted on November 1, 2025

Splash of Rainbow, South Tufa, Mono Lake

Sony α1

Sony 16-35 GM II

6 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

As landscape photographers, it’s easy to arrive at a photo location with a preconceived idea of what we’re going to shoot. That’s often because there’s a single perspective that gets all the attention, dominating the images of the location shared online and skewing the perception of what its images should look like.

Stillness, South Tufa, Mono Lake

At Mono Lake, despite its sprawling layout with lake views that span 270 degrees, photographers (myself included) tend to gravitate the east-facing beach with a solitary tufa tower that resembles a battleship floating just a couple hundred feet offshore. I can’t deny that it’s a striking feature worthy of photographing, but certainly not to the exclusion of other opportunities at South Tufa.

Fortunately, since this spot is at the most distant corner of South Tufa, getting out there requires walking past most of the other views on the route. So each time I take a workshop group for its first visit to South Tufa, as I guide them out to this distant beach, I make a point of emphasizing all the possibilities along the way, encouraging them to stick with me all the way out to the battleship view, but to file away other scenes they might want to return to as they go.

But photography at South Tufa isn’t just about the views—equally important is the light. So another point I try to emphasize on that initial walk is understanding—given that there are photo-worthy views that include both lake and tufa facing east, north, and west—how much the scene will change with the direction of the sunlight. Since our first visit is usually a sunset shoot, I remind everyone how different the light will be when we return for sunrise the next morning. I point out where the sun will rise and encourage them to visualize the different light we’ll see that will opportunities in multiple directions, and to identify potential compositions that might work in that light.

Since we’d been there the prior evening, as soon as this year’s group arrived dark and early on this autumn morning, everyone scattered quickly. I brought up the rear, checking in with everyone on my walk out to the battleship tufa beach. As much as I like the scene at this east-facing beach, one challenge is that it’s in the midst of what might be best describes as a tufa garden—a collection of stubby shrubs and 10-15 foot high tufa towers—that makes it very difficult to see what’s happening in the other directions. But with a nice mix of clouds and sky this morning, I knew the potential existed for a nice sunrise and made a point of keeping my head on a swivel to avoid missing something in the other directions.

About 15 minutes before sunrise I noticed the clouds in the west start catching light, and shortly thereafter the Sierra peaks in the same direction lit up. I let the near me know that this might be a good time to wander over to the other side of the tufa garden and headed in that direction. The walk to the other side is probably less than 100 feet, but by the time I got there the light on the base of the clouds had intensified significantly. And much to my amazement—given that there was no sign of rain here, nor any rain at all forecast for the area that morning—realized that a splash of rainbow was perched atop the hills across the lake.

Not knowing how long the rainbow would last, I ran around hailing as many in my group as possible, and we all went straight to work trying to make a photo before it went away. I’m a strong proponent of finding compositions where all the elements work together, which is no small feat at South Tufa, given all the randomly situated tufa towers and rocks jutting from the water. Fortunately, as I moved around trying to organize all the visual elements in my scene, not only did the rainbow seem to be waiting for me to finish, it actually intensified as I did it.

It probably didn’t take more than a minute or two, but it felt like forever before I found a composition that satisfied me. As you can see, this rainbow was never destined to be the main subject—at its best it was simply a colorful accent to an already beautiful scene. But what an accent it was.

In addition to the distant rainbow and sunlit clouds, the other important elements I needed to organize were primarily in my foreground: the tufa peninsula jutting in from the left; the small tufa island at my feet, the submerged tufa stones; and (especially) the reflection.

To make all this work together, I started by centering the little island in my frame, and balancing the rainbow with the tallest spire of the peninsula. With the scene left/right balanced, I decided I need to get my boots muddy and set my tripod in shallow water to turn the foreground tufa into an actual island. Since the best clouds were fairly low, I only included enough sky to include them (by putting the top of my frame where I did, viewers can infer that the clouds stretch much farther than they did), and was careful not to put the little blip of tufa on the far right too close to the edge.

Now for the reflection. I didn’t really care for the empty water between the reflection and the little island, so I slowly dropped my tripod, keeping an eye on my LCD and stopping when the reflection filled almost all of that watery void. I put on my Breakthrough 6-stop dark polarizer to smooth the water, and it to reveal the interesting detail on the lakebed without erasing the colorful part of the reflection. Finally, I focused on the small rocks just beyond my foreground island, and clicked.

This is not a scene I’d have normally gravitated to, but I was drawn by the light (and stayed for the rainbow). Had I not seen the rainbow, I’m not even sure I’d have taken the time to build the composition I ended up with, but this is just one more reminder that if you open your mind and your eyes, things just have a way of working out.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Mono Views

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Eastern Sierra, Mono Lake, rainbow, reflection, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM II, Sony Alpha 1, South Tufa Tagged: Eastern Sierra, Mono Lake, nature photography, Rainbow, reflection, South Tufa

Hold My Gear (the Sequel)

Posted on October 18, 2025

Color and Clouds, North Lake Autumn Reflection, Eastern Sierra

Sony α1

Sony 16-35 GM II

1/100 seconds

F/9

ISO 100

After sharing in my prior post that I’ve been lugging a 30 pound camera bag through airports, it occurred to me that I haven’t updated you on the ever-changing contents of said camera bag lately. But before I continue, let me remind you that a photographer’s gear choice is no more relevant to his images than a writer’s pen is to her stories, or a chef’s cutlery is to her cuisine. Yes, these choices might make a difference on the fringe, but I imagine most would agree that a great chef will almost certainly get better results with Kirkland knives (with all due respect to Costco) than an average chef would get with top-of-the-line Zwilling.

But that doesn’t mean that I would voluntarily discard my current gear for some other brand. Far from it. I love the gear I use, and am always happy to share why. So what follows is a revised version of the first Hold My Gear post, from 2021—below that, you’ll find the story of today’s image.

I’ll start with my camera bag

Shimoda Action X50 with a Large Core Unit: This bag simply checks all the boxes for me: for starters, it’s large enough to carry everything I consider essential, with room to spare for a few things that are less than essential and that may change depending on the trip and my objective. In addition to 2 bodies and 5 lenses, it fits all the miscellany I always want with me (headlamp, rain and/or cold weather apparel, extra batteries and media cards, tools, among many things).

But more than capacity, my bag also needs to be comfortable on long hikes—whether across rugged High Sierra terrain, Iceland’s winter icescapes, or the endless concourses of Sydney International Airport—and (just as important) it must fit fully loaded into any overhead compartment I encounter. My Shimoda passes all these tests with flying colors.

Always in my bag

- Sony a7R V and Sony a1 bodies

- Sony 12-24 f/2.8 GM lens: Though I don’t use it as much as a couple of other lenses, having a lens as wide as 12mm allows me to photograph things I never could before, and I love that it’s still relatively compact.

- Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM II lens (plus a Breakthrough polarizer), which is usually mounted on the a1: This focal range is covered by other lenses in my bag, but I love the lens too much to leave it behind—crazy sharp, and f/2.8 means it’s fast enough for night photography in a pinch. Plus, unlike the 12-24, I can use it with conventional polarizing and ND filters.

- Sony 24-105 G lens (plus a Breakthrough polarizer), which is usually mounted on the a7R V: Not only is this lens wonderfully sharp, its middle-of-the-road focal range fits so many situations—it’s no wonder this lens is my workhorse.

- Sony 100-400 GM lens (plus a Breakthrough polarizer): Replacing my 70-200 with this slightly bigger lens doubled my focal range, without adding tons of extra weight—and it’s a good match with the Sony 1.4X teleconverter.

- (Usually) Sony 14mm f/1.8 GM lens: This is my night lens, and though I only use it at night and don’t do night photography on every trip, since I have a slot for it and it’s not too heavy, my 14 GM usually just lives in my camera bag.

- Sony 1.4X teleconverter—I used to use the 2X, but found a noticeable sharpness improvement after switching to the 1.4X.

- Filters: Breakthrough 72mm and 77mm neutral polarizers (nearly fulltime on the 16-35, 24-105, and 100-400 lenses), Breakthrough 72mm and 77mm 6-Stop Dark polarizing filters (to switch out with my standard polarizers when I need a longer shutter speed).

- Memory cards: Each camera has two 128 GB Sony Tough cards, then I have a handful of other 128 GB and 64 GB SD cards rattling around in a pocket, just in case.

- Other stuff: Lens cloths, headlamp, insulated water bottle, extension tubes, memory cards, multiple spare batteries, Giotto Rocket Blower, and a couple of Luna Bars (because photography always trumps meals).

Specialty Equipment (lives in a second camera bag that gets tossed in the back of the car and stays there when I don’t need to fly to my destination)

- Sony 20mm f/1.8 G lens: For Milky Way and other moonless night photography—this one’s even more compact than the 24mm.

- Sony 24mm f/1.4 GM lens: For Milky Way and other moonless night photography—I can’t believe how compact this lens is.

- Sony 90mm Macro: I use this lens a lot with extension tubes to get super close for my creative selective focus work (wildflowers, fall color).

- Sony 200-600 G lens: When I want to go big on a moonrise/moonset—often pared with the 1.4x teleconverter. I also use this lens with extension tubes for selective focus fall color and wildflowers.

- 2 Stepping Stone LT-IV Lightning Triggers

Support

- Really Right Stuff Ascend-14L tripod with integrated head: Absolutely the best combination of light, tall, and sturdy I’ve ever found in a tripod. It’s so light and compact that I just attach it to my camera bag, even when flying, and just forget about it until it’s time to shoot (never a problem with TSA).

- Really Right Stuff 24L Tripod with a RRS BH-55 ball head: Sturdy enough for whatever I put on it, in pretty much whatever conditions I encounter. I also like that, even though it doesn’t have a centerpost, when fully extended (plus the head and camera), it’s several inches taller than I am. As much as love my Ascend, this is my tripod of choice in strong wind, or when I’m shooting extra long. As with my bag that carries my specialty lenses, this tripod usually lives in the back of my car and doesn’t usually fly with me (it would need to go in the suitcase), but is always available when I drive to a destination.

A few words about today’s image

Thanks to a great group and beautiful conditions, this year’s Eastern Sierra workshop was a great success. Though today’s image didn’t come during the workshop, you could call it ES workshop adjacent, because it came the day before the workshop, on my annual pre-workshop scouting visit to North Lake.

As familiar as I am with all my locations, I hate taking my groups to locations I haven’t been to in a year, because you just never know what might have changed. That’s especially important when the goal is fall color, which can vary significantly from year to year. It’s not always practical to pre-scout every location, but I do my best to make it happen when I can.

For my Eastern Sierra workshop, I always leave early the morning of the day before the workshop, which gives me time to hit all my spots on the way down. I can make it as far as Bishop, which makes for a long day, but from Bishop can finish my scouting the next morning by driving the final hour to Lone Pine, and leaving early enough to get eyes on my Lone Pine locations (Whitney Portal, Mt. Whitney, and the Alabama Hills) before the workshop starts that afternoon.

With the workshop always starting a Monday, Sunday is dedicated to scouting my locations. But this year’s Sunday scouting mission was a little problematic because I’d only just returned from Jackson Hole at 9 p.m. Saturday night, after assisting Don Smith’s Grand Teton National Park workshop (I’d get instant payback because Don would be assisting my Eastern Sierra workshop). After unpacking and repacking, the plan was to rise dark and early Sunday morning and be on the road by 7:00 a.m. This year, instead of bounding out the door at 7:00, I pretty much dragged myself out (with a shove from my wife) closer to 8:30. Still enough time, but not a lot of wiggle room.

I perked up pretty quickly once on the road, helped no doubt by an intermittent light-to-moderate rain that followed me down 395, and (especially) the beautiful clouds that came with it—a significant upgrade from the chronic blue skies that often plague this trip.

To ensure that I made it up to North Lake before dark, I didn’t take my usual swing through the June Lake Loop, and skipped the drives up to the McGee Creek and Mosquito Flat trailheads as well. Since these aren’t workshop stops (though I do recommend them as possible extra locations for anyone looking to photograph more color on the drive from Bishop to our Lee Vining hotel on Day 3), I felt okay about missing them in favor of North Lake.

On the steep ascent up Bishop Creek Canyon, I got a front row view of the peaks playing hide and seek with the clouds. By the time I climbed the last mile on the (mostly) unpaved, one-lane road to North Lake, a few sprinkles dotted my windshield. With so much workshop prep on my mind, I virtually never photograph at any point on this pre-workshop scouting trip, but for some reason (beautiful sky), this time I swung my camera bag onto my back for the 100-yard walk from the parking area to the lakeshore. I was beat, and hungry, and with darkness coming soon, I just wanted to get back to Bishop to check-in to my hotel to prepare (and rest up) for the workshop—but if the lake is real nice, maybe I’ll fire off a couple of frames before calling it a day.

The color couldn’t have been better, and the clouds were off the charts. A couple of other photographers were set up on the lakeshore where I usually like to shoot the reflection, but with a light breeze spreading small ripples across the water, I passed on the reflection in favor of the gold and green grass to fill my foreground.

After about five minutes I was pretty happy with what I had and was just about to pack up when I noticed that the water across the lake had flattened out, and a reflection had formed. It was a long way away and hardly visible, but looking closer, I could see the stillness expanding toward me. Soon—in no more than a minute—the entire lake surface a calmed to a reflection and all thoughts of leaving vanished.

With my usual reflection spot occupied, I moved about 30 feet closer to the road, to a tiny micro-cove sheltered by grass and a large rock. Here you can’t get as much reflection, but being so sheltered, it’s usually the last place the reflection leaves if a breeze picks up.

Given the narrowness of my foreground reflection here, combined with beautiful clouds and light high above, I opted for a vertical composition. Dropping lower, I positioned myself to include two small rocks as foreground anchors, then composed wide to include as much sky and reflection as possible.

Despite occasional sprinkles, the rain mostly held off and I ended up staying for nearly an hour, finally moving over to my usually spot when the other photographers moved on.

This was Sunday evening. I returned with my group for sunrise Wednesday morning. I was pretty confident the color would still be great, but crossed my fingers all the way up the canyon hoping we’d get a reflection. I was right about the color, and the reflection gods smiled on us as well, delivering an absolutely flawless mirror atop the water. We also had a couple of clouds, but nothing like my evening a couple of nights earlier, and as excited as my group was, I didn’t have the heart to tell them that I had it even better.

I Love Reflections (Perhaps You Noticed)

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: aspen, fall color, North Lake, Photography, reflection, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM II, Sony Alpha 1 Tagged: autumn, Eastern Sierra, fall color, nature photography, North Lake, reflection

Do You Really Need a New Camera?

Posted on November 22, 2024

I had an idea germinating for this week’s blog post, but when Sony announced the brand new α1 II Tuesday, I pivoted to an experienced-based public service message. (You’re welcome.)

As you may have noticed, a new camera purchase is a significant investment. Nevertheless, for many photographers the new camera decision seems more emotional than rational. Case in point: Me. That is, once upon a time (okay, as recently as a couple of years ago), I’d have been all over this week’s Sony announcement, and by now almost certainly would have already ordered my new camera—regardless of how great my current camera is.

This new-camera purchase reflex takes me back to my first grown-up job, working for a small independent vehicle leasing company in the San Francisco Bay Area. “Independent” meant we were not affiliated with any auto manufacturer or dealership, which enabled us to offer our customers any make or model of vehicle and freed me to make honest recommendations rather than push a particular model. Handling every kind of car imaginable, from Toyota to Porsche to Rolls Royce, I soon noticed that many of my leasing customers seemed to be intent on replacing their perfectly excellent car (or truck) that still had lots of useful years remaining. It seemed they’d become so blinded by the allure of “new” that they’d lost contact with rational thought. Though their lease payments would persist for years after the car’s “new” wore off, they seemed to believe that driving this new Whatever would somehow make their life complete—trying to talk them down was fruitless. Sigh.

You’d think that experience would have immunized me against making similar emotional purchases, but sadly, I too have fallen into the trap of coveting the latest and greatest. In my case it hasn’t been cars (I do love new cars, but I usually wait 8-10 years between purchases, and only when I have enough saved to avoid car payments). No, my irrational exuberance skews more toward technology.

For example, many years ago I got sucked into Apple’s iPhone upgrade program (pay a monthly fee for the newest model, then return it for the next model as soon as it’s released) and so far haven’t been able to extricate myself (this is my weakness—it’s not like leaving Apple’s upgrade program is like trying to cancel a gym membership). And for more than a decade, I replaced my Intel-based Macs every 2 or 3 years. Fortunately, this costly predisposition was cured by Apple’s M processors, which are good enough to prevent me from fabricating any kind of credible rationalization for upgrading. So yay me.

Anyway, back to the camera thing. Earning my living as a photographer, it’s always been easy to justify buying the latest camera model. But despite all the marketing hype to the contrary (this applies to all manufacturers, not just the brand I use, Sony), I realized long ago that I’ll probably notice very little (or no) practical improvement in image quality from the new model—especially since I’m almost always replacing the model immediately preceding the new one. So what was my motivation? Being completely honest with myself, a large part of the appeal was simply the idea of owning the latest and greatest.

Given that my current cameras, a Sony a7RV and Sony α1, are everything I need (and more), my rational mind tells me that simply can’t justify spending $6500 to replace one. This isn’t a new insight, but what is new is that this time my rational mind is winning. In previous upgrade iterations, I’ve sometimes used the “photography needs to make you happy” mantra to rationalize the new purchase. After trying that on for this camera, I had to acknowledge that the is fallacy in my argument is confusing pleasure for happiness: Yes, getting that new camera will indeed give me a great deal of pleasure, but when transient pleasure comes at the price of enduring happiness, the biggest winner is Sony (or whoever your camera manufacturer is).

The truth is, regardless of who makes your camera (they’re all great), today’s (and yesterday’s as well) cameras capabilities surpassed the needs of most photographers many years ago. And no matter how great the marketing promoting the latest upgrade makes the camera sound, most photographers have better things to do with their money.

Am I saying you shouldn’t upgrade your camera? Absolutely not. I’m saying the criterion for springing for a camera upgrade shouldn’t simply be, “Is the new camera better than the camera I have?” (it almost certainly is); it should be, “Will the new camera make an appreciable difference in my photography?” (it probably won’t).

Here are some thoughts to bring to your next camera purchase:

- Filter the hype. Manufacturers are really good at spinning modest improvements into “game changing” essentials. Don’t buy it.

- Never, never, never chase megapixels. I can pretty much guarantee that you already have more megapixels than you’ll ever need, but megapixels sell. Until the photography public gets wise to the fact that adding resolution comes at the cost of image quality (really), manufacturers will keep giving us pixels we don’t need.

- Upgrade your more permanent gear first. Lenses and tripods might not be as sexy as a new camera, but there’s a decent chance you’ll notice more improvement in your images by upgrading your lenses and tripod than upgrading your camera.

- Take a trip. If you have all the lenses you need and already own the tripod of your dreams, consider spending that new camera money visiting locations you’ve always wanted to photograph. (Or sign up for that photo workshop you’ve had your eye on. Just sayin’….)

- And don’t forget, the longer you wait, the better your next camera will be. Seriously, your new camera, no matter how great, will probably be “obsolete” within a couple of years.

I need to make it clear that this is in not a review, or an indictment, of the Sony α1 II. I haven’t seen the camera, and have only scanned the (impressive) specs and (predictably hyperbolic) marketing claims. It looks like a fantastic camera. But as with any new camera, if it doesn’t add something that you believe will make a significant difference in your photography, there are probably better things to do with your money.

So what would induce me to replace one of my cameras? Believe it or not, fewer megapixels. Despite the perception (and marketing claims) to the contrary, megapixels are not a measure of image quality, they’re a measure of image size. Period. For any given technology, the fewer the number of photosites (measured in megapixels), the better the camera’s image quality will be. That camera manufacturers can continue cramming more and more photosites onto a 35mm sensor without sacrificing image quality speaks to the progress of technology. But the only way they can add photosites to a fixed space (like a 35mm sensor) is to shrink them, and/or reduce the distance separating them. Imagine the image quality spike we’d see if instead more photosites, they took the technological advances that enables more photosites without sacrificing dynamic range and high ISO performance, and created a sensor with larger (better light gathering) and more spread out (cooler) photosites.

Of course your priorities may (probably are) be different from mine, so I can’t tell you whether any new camera is right for you and your situation. Just don’t fall into the trap of buying the next model simply because it’s “better,” because where technology is concerned, better is quite possibly not good enough.

I return you now to your regular programming…

On my way back to the parking area following an especially nice North Lake sunrise shoot, a stand of aspen grabbed my eye. I knew I was well into the 1o minutes I’d given the group to wrap up and make the short walk back to the cars (the light was changing fast and I had two more stops in mind), but these aspen were just too perfect to resist: backlit leaves at peak fall color, parallel trunks, and pristine white bark.

With the clock ticking (it’s never a good look when the leader is one everyone is waiting for), I’d normally just take a couple of iPhone snaps to preserve a beautiful scene I don’t have the time to do justice with a “serious” image. Even though I rarely do anything with these quick iPhone snaps, I find it hard to just walk away from scenes like this without a record of having witnessed it.

But in this case, my phone was buried deep in a pocket of one of my seemingly infinite layers of clothing. On the other hand, I (for some reason I can’t remember) was carrying my camera (which I usually return to my camera bag when I finish a shoot). So rather than mine for my phone, I turned my camera on, put it to my eye, and squeezed off a couple of frames, before continuing to the cars.

Because I have such a strong (irrational?) tripod bias (click, evaluate, refine, repeat…), I honestly didn’t think about these pictures again for the rest of the workshop. But going through my images after the trip, these aspen images stopped me. Slowly the memory of my quick stop returned, and as I spent more time with them, the more I liked what I saw.

Processing this image, and as much as I liked it, I could also tell that I didn’t give the scene my usual (obsessive) attention to detail, quickly identifying a few things I’d have done differently if I’d taken a little more time. For example, I’d probably have shifted around a bit to see if I could eliminate, or at least minimize, some of the gaps in the foliage, and to get a little more separation between some of the trunks. And I’d definitely have paid more attention to some of the minor distractions on the frame’s border. But despite these oversights, I was surprised by how much I like this image, and how well it captures so much about what I love about aspen.

So I guess the moral of this story is, even though a tripod almost always makes my pictures better, just because I can’t use one doesn’t mean I shouldn’t take the picture.

Join my next Eastern Sierra photo workshop

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

If you’ve made it this far, thank you. If you enjoy reading my blog, please share it with your friends.

More Aspen

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: aspen, Eastern Sierra, fall color, North Lake, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V Tagged: aspen, autumn, Eastern Sierra, fall color, nature photography, North Lake

Gifts From Heaven

Posted on November 3, 2024

Heaven Sent, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS Above the Sierra Crest, Alabama Hills

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 3200

f/4

5 seconds

As much for its (apparently) random arrival as its ethereal beauty, the appearance of a comet has always felt to me like a gift from the heaven. Once a harbinger of great portent, scientific knowledge has eased those comet fears, allowing Earthlings to simply appreciate the breathtaking display.

Unfortunately, scientific knowledge does not equal perfect knowledge. So, while a great comet gives us weeks, months, or even years advance notice of its approach, we can never be certain of how the show will manifest until the comet actually arrives. For every Comet Hale-Bopp, that gave us nearly two years warning before becoming one of the most widely viewed comets in human history, we get many Comet ISONs, which ignited a media frenzy more than a year before its arrival, then completely fizzled just as the promised showtime arrived. ISON’s demise, as well as many highly anticipated comets before and after, taught me not to temper my comet hopes until I actually put eyes on the next proclaimed “comet of the century.” Nevertheless, great show or not, the things we do know about comets—their composition, journey, arrival, and (sometimes) demise—provide a fascinating backstory.

In the simplest possible terms, a comet is a ball of ice and dust that’s (more or less) a few miles across. After languishing for eons in the coldest, darkest reaches of the Solar System, perhaps since the Solar System’s formation, a gravitational nudge from a passing star sends the comet hurtling sunward, following an eccentric elliptical orbit—imagine a stretched rubber band. Looking down on the entire orbit, you’d see the sun tucked just inside one extreme end of the ellipse.

The farther a comet is from the sun, the slower it moves. Some comets take thousands, or even millions, of years to complete a single orbit, but as it approaches the sun, the comet’s frozen nucleus begins to melt. Initially, this just-released material expands only enough to create a mini-atmosphere that remains gravitationally bound to the nucleus, called a coma. At this point the tail-less comet looks like a fuzzy ball when viewed from Earth.

This fuzzy phase is usually the state a comet is in when it’s discovered. Comets are named after their discoverers—once upon a time this was always an astronomer, or astronomers (if discovered at the same time by different astronomers), but in recent years, most new comets are discovered by automated telescopes, or arrays of telescopes, that monitor the sky, like ISON, NEOWISE, PANSTARRS, and ATLAS. Because many comets can have the same common name, astronomers use a more specific code assembled from the year and order of discovery.

As the comet continues toward the sun, the heat increases further and more melting occurs, until some of the material set free is swept back by the rapidly moving charged particles of the solar wind, forming a tail. Pushed by the solar wind, not the comet’s forward motion, the tail always fans out on the side opposite the sun—behind the nucleus as the comet approaches the sun, in front of the comet as it recedes.

Despite accelerating throughout its entire inbound journey, a comet will never move so fast that we’re able to perceive its motion at any given moment. Rather, just like planets and our moon, a comet’s motion relative to the background stars will only be noticeable when viewed from one night to another. And like virtually every other object orbiting the sun, a comet doesn’t create its own light. Rather, the glow we see from the coma and tail is reflected sunlight. The brilliance of its display is determined by the volume and composition of the material freed and swept back by the sun, as well as the comet’s proximity to Earth. The color reflected by a comet’s tail varies somewhat depending on its molecular makeup, but usually appears as some shade of yellow-white.

In addition to the dust tail, some comets exhibit an ion tail that forms when molecules shed by the comet’s nucleus are stripped of electrons by the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Being lighter than dust molecules, these ions are whisked straight back by the solar wind. Instead of fanning out like the dust tail, these gas ions form a narrow tail that points directly away from the sun. Also unlike the dust tail that shines by reflected light, the ion tail shines by fluorescence, taking on a blue color courtesy of the predominant CO (carbon monoxide) ion.

One significant unknown upon discovery of a new comet is whether it will survive its encounter with the sun at all. While comets that pass close to the sun are more likely to shed large volumes of ice and dust, many sun-grazing comets approach so close that they’re overwhelmed by the sun’s heat and completely disintegrate.

With millions of comets in our Solar System, it would be easy to wonder why they’re not a regular part of our night sky. Actually, Earth is visited by many comets each year, though most are so small, and/or have made so many trips around the sun that they no longer have enough material to put on much of a show. And many comets never get close enough to the sun to be profoundly affected by its heat, or close enough to Earth to shine brightly here.

Despite all the things that can go wrong, every once in a while, all the stars align (so to speak), and the heavens assuage the disappointment of prior underachievers with a brilliant comet. Early one morning in 1970, my dad woke me and we went out in our yard to see Comet Bennett. This was my first comet, a sight I’ll never forget. I was disappointed by the faint smudges of Comet Kohoutek in 1973 (a complete flop compared to its advance billing), and Halley’s Comet in 1986 (just bad orbital luck for Earthlings). Comet Hale-Bopp in 1996 and 1997 was wonderful, while Comet ISON in 2012 disintegrated before it could deliver on its hype.

In 2013 Comet PANSTARRS didn’t put on much of a naked-eye display, but on its day of perihelion, I had the extreme good fortune to be atop Haleakala on Maui, virtually in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. Even though I couldn’t see the it, using a thin crescent moon I knew to be just 3 degrees from the comet to guide me, I was able to photograph PANSTARRS and the moon together. Then, in the dismal pandemic summer of 2020, Comet NEOWISE surprised us all to put on a beautiful show. I made two trips to Yosemite to photograph it, then was able to photograph it one last time at the Grand Canyon shortly before it faded from sight.

October 2024 promised the potential for two spectacular comets, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS (C/2023 A3) in the first half of the month, and Comet ATLAS (C/2024 S1) at the end of the month. Alas, though this second comet had the potential to be much brighter, it pulled an Icarus and flew too close to the sun (RIP). But Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was another story, brightening beyond expectations.

I shared the story of my trip to photograph Tsuchinshan–ATLAS in my October 16 I’m Not Crazy, I Swear… blog post, but have a couple of things to add about this image. First is how important it is to not get so locked into one great composition that you neglect capturing variety. I captured this wider composition before the image I shared a couple of weeks ago, and was pretty thrilled with it—thrilled enough to consider the night a great success. But I’m so glad that I changed lenses and got the tighter vertical composition shortly before the comet’s head dropped out of sight.

And second is the clearly visible anti-tail that was lost in thin haze near the peaks in my other image. An anti-tail is a faint, post-perihelion spike pointing toward the sun in some comets, caused when larger particles from the coma, too big to be pushed by the solar wind, are left behind. It’s only visible from Earth when we pass through the comet’s orbital plane. Pretty cool.

When will the next great comet arrive? No one knows, but whenever that is, I hope I’ve kindled enough interest that you make an effort to view it. But if you plan to chase comets, either to photograph or simply view, don’t forget the wisdom of astronomer and comet expert, David Levy: “Comets are like cats: they have tails, and do precisely what they want.”

Join me in my Eastern Sierra photo workshop

More Gifts From Heaven

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

I’m Not Crazy, I Swear…

Posted on October 16, 2024

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and Mt. Whitney, Alabama Hills, California

Sony α1

Sony 100-400 GM

5 seconds

f/5.6

ISO 3200

Crazy is as crazy does

In college, my best friend and I drove from San Francisco to San Diego so he could attend a dental appointment he’d scheduled before his recent move back to the Bay Area. We drove all night, 10 hours, arriving at 7:55 a.m. for his 8:00 a.m. appointment (more luck than impeccable timing). I dozed in the car while he went in; he was out in less than an hour, and we drove straight home. I remember very little of the trip, except that each of us got a speeding ticket for our troubles. Every time I’ve told that story, I’ve dismissed it with a chuckle as the foolishness of youth. Now I’m not so sure that youth had much to do with it at all.

I’m having second thoughts on the whole foolishness of youth thing because on Monday, my (non-photographer) wife and I drove nearly 8 hours to Lone Pine so I could photograph Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS setting behind Mt. Whitney. We arrived at my chosen location in the Alabama Hills about 15 minutes after the 6:20 sunset, then waited impatiently for the sky to darken enough for the comet to appear. I started photographing at around 7:00, and was done when the comet’s head dropped below Mt. Whitney at 7:30. After spending the night in Lone Pine, we left for home first thing the next morning, pulling into the garage just as the sun set. For those who don’t want to do the math, that’s 16 hours on the road for 30 minutes of photography.

In my defense, for this trip I had the good sense (and financial wherewithal) to get a room in Lone Pine Monday night, and didn’t get pulled over once. That this might have been a crazy idea never occurred to me until I was back at the hotel, and that was only in the context of how the story might sound to others—in my mind this trip was worth every mile, and I have the pictures to prove it.

I say that fully aware that my comet pictures will no doubt be lost in the flood of other Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS images we’ll see over the next few weeks, many no doubt far more spectacular than mine. My excitement with the fruits of this trip is entirely personal, and to say I’m thrilled to have witnessed and photographed another comet would be an understatement—especially in light of last month’s Image of the Month e-mail citing comets as one of the three most beautiful celestial subjects I’ve ever witnessed. And of those three, comets feel the most personal to me.

Let me explain

When I was ten, my best friend Rob and I spent most of our daylight hours preparing for our spy careers—crafting and trading coded messages, surreptitiously monitoring classmates, and identifying “secret passages” that would allow us to navigate our neighborhood without being observed. But after dark our attention turned skyward. That’s when we’d set up my telescope (a castoff generously gifted by an astronomer friend from my dad’s Kiwanis Club) on Rob’s front lawn (his house had a better view of the sky than mine) to scan the heavens hoping that we might discover something: a comet, quasar, supernova, black hole, UFO—it didn’t really matter. And repeated failures didn’t deter us.

Nevertheless, our celestial discoveries, while not Earth-changing, were personally significant. Through that telescope we saw Jupiter’s moons, Saturn’s rings, and the changing phases of Venus. We also learned to appreciate the vastness of the universe with the observation that, despite their immense size, stars never appeared larger than a pinpoint, no matter how much magnification we threw at them.

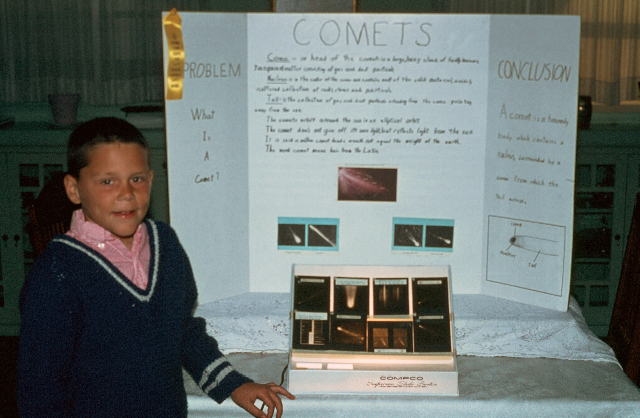

To better understand what we saw, Rob and I turned to illustrated astronomy books. Pictures of planets, galaxies, and nebula amazed us, but we were particularly drawn to the comets: Arend-Roland, Ikeya–Seki, and of course the patriarch of comets, Halley’s Comet (which we learned was scheduled to return in 1986, an impossible wait that might as well have been infinity). With their glowing comas and sweeping tails, it was difficult to imagine that anything that beautiful could be real. When it came time to choose a subject for the annual California Science Fair, comets were an easy choice. And while we didn’t set the world on fire with our project presentation, Rob and I were awarded a ribbon of some color (it wasn’t blue), good enough to land us a spot in the San Joaquin County Fair. (Edit: Uncovering the picture, I see now that our ribbon was yellow.)

Here I am with the fifth grade science project that started it all. (This is only half of the creative team—somewhere there’s a picture that includes Rob.)

The next milestone in my comet obsession occurred a few years later, after my family had moved to Berkeley and baseball had taken over my life. One chilly winter morning my dad woke me and urged me outside to view what I now know was Comet Bennett. Mesmerized, my smoldering comet interest flamed instantly, expanding to include all things astronomy. It stayed with me through high school (when I wasn’t playing baseball), to the point that I actually entered college with an astronomy major that I stuck with for several semesters, until the (unavoidable) quantification of the concepts I loved sapped the joy from me.

While I went on to pursue other things, my affinity for astronomy continued, and comets in particular remained special. Of course with affection comes disappointment: In 1973 Kohoutek fizzled spectacularly, a failure that somewhat prepared me for Halley’s anticlimax in 1986.

By the time Halley’s arrived, word had come down that it was poorly positioned for its typical display (“the worst viewing conditions in 2,000 years”), making it barely visible this time around, but I can’t wait until 2061! (No really—I can’t wait that long. Literally.) Nevertheless, venturing far from the city lights one moonless January night, I found great pleasure locating without aid (after much effort), Halley’s faint smudge in Aquarius.

After many years with no naked-eye comets of note, 1996 arrived with the promise of two great comets. While cautiously optimistic, Kohoutek’s scars prevented me from getting sucked in by the media frenzy. So imagine my excitement when, in early 1996, Comet Hyakutake briefly approached the brightness of Saturn, with a tail stretching more than twenty degrees (forty times the apparent width of a full moon).

But as beautiful as it was, Hyakutake proved to be a mere warm-up for Comet Hale-Bopp, which became visible to the naked eye in mid-1996 and remained visible until December 1997—an unprecedented eighteen months. By spring of 1997 Hale-Bopp had become brighter than Sirius (the brightest star in the sky), its tail approaching 50 degrees. I was in comet heaven. But alas, family and career had preempted my photography pursuits and I didn’t photograph Hale-Bopp.

Comet opportunities again quieted after Hale-Bopp. Then, in early 2007, Comet McNaught caught everyone off-guard, intensifying unexpectedly to briefly outshine Sirius, trailing a thirty-five degree, fan-shaped tail. McNaught put on a much better show in the Southern Hemisphere; in the Northern Hemisphere, because of its proximity in the sky to the sun, it provided a very small window of visibility, and was easily lost in the bright twilight. This, along with its sudden brightening, prevented McNaught from becoming the media event Hale-Bopp was. I only found out about it by accident, on the last day it would be easily visible in the Northern Hemisphere. By then digital capture had rekindled my photography interest (understatement), so despite virtually no time to prepare, I grabbed my camera and headed to the foothills east of Sacramento, where I managed to capture the McNaught image I share in the gallery below—my first successful comet capture.

Following McNaught, I vowed not to be caught off guard by a comet again. After enduring the frustration of promising (over-hyped?) comets disintegrated by the sun (you broke my heart, Comet ISON), and seeing others’ images of spectacular Southern Hemisphere-only comets (I’m looking at you, Comet Lovejoy), my heart jumped when I came across a website proclaiming the approach of Comet PANSTARRS (a.k.a, C/2011 L4 in less glamorous astro-nerd parlance), discovered not by an individual, but by the Pan-STARRS automated telescope array atop Haleakala on Maui.

Researching further, I learned that PANSTARRS could (fingers crossed) hang low in the western sky at magnitudes brighter than Saturn, for about a week right around its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) in March 2013, remaining visible as it rises but dims over the following few weeks. Checking my calendar to see if I had any conflicts that week, I realized I’d be on Maui for my workshop during PANSTARRS’ perihelion! Turns out my first viewing of PANSTARRS was atop Haleakala, almost literally in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. I also got to photograph a rapidly fading PANSTARRS above Grand Canyon on its way back to the farthest reaches of the Solar System.

Then, in 2020, came Comet NEOWISE to brighten our pandemic summer. I was able to make two trips to Yosemite and another to Grand Canyon to photograph NEOWISE (the Yosemite trips were for NEOWISE only).

One more time

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS has been on my radar for at least a year, but not something I monitored closely until September, when it became clear that it was brightening as, or better than, expected. By the end of September I knew that the best Northern Hemisphere views of Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would be in mid-October, but since I was already in the Alabama Hills at the end of September, just a couple of days after the comet’s perihelion, I went out to look for it in the pre-sunrise eastern sky (opposite the gorgeous Sierra view to the west). No luck, but that morning only solidified my resolve to give it another shot when it brightened and returned to the post-sunset sky.

At that point I had no detailed plan, and hadn’t even plotted its location in the sky beyond knowing it would be a little above the western horizon shortly after sunset in mid-October. My criteria were a nice west-facing view, distant enough to permit me to use a moderate telephoto lens. After ruling out the California coast (no good telephoto subjects) and Yosemite Valley (no good west-facing views), I soon realized I’d be returning to the east side of the High Sierra.

At that point I started working on more precise coordinates and immediately eliminated my first (and closest) candidate, Olmsted Point, because the setting comet didn’t align with Half Dome. My next choice was Minaret Vista (near Mammoth), a spectacular view of the jagged Minaret range and nearby Mt. Ritter and Mt. Banner. This was a little more promising—the alignment wasn’t perfect, but it was workable. Then I looked at the Alabama Hills and Mt. Whitney and knew instantly I’d be reprising the long drive back down 395 to Lone Pine.

Though its intrinsic magnitude faded each day after its September 27 perihelion, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS’s apparent magnitude (visible brightness viewed from Earth) continued to increase until its closest approach to Earth on October 12. While its magnitude would never be greater than it was on October 12, the comet was still too close to the sun to stand out against sunset’s vestigial glow. But each night it climbed in the sky, a few degrees farther from the sun, toward darker sky.

Though Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would continue rising into increasingly dark skies through the rest of October, and each night would offer a longer viewing window than the prior night, I chose October 14 as the best combination of overall brightness and dark sky. An added bonus for my aspirations to photograph the comet with Mt. Whitney and the Sierra Crest would be the 90% waxing gibbous moon rising behind me, already high enough by sunset to nicely illuminate the peaks after dark, but still far enough away not to significantly wash out the sky surrounding the comet.

At my chosen spot, I set up two tripods and cameras, one armed with my Sony a7RV and 24-105 lens, the other with my Sony a1 and 100-400 lens. I selected that first location because it put the comet almost directly above Mt. Whitney, 16 degrees above the horizon, at 7 p.m. But since the Sierra crest rises about 10 degrees above the horizon when viewed from the Alabama Hills, I knew going in that the comet’s head would slip behind the mountains at 7:30, slamming shut my window of opportunity after only 30 minutes.

When it first appeared, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was high enough that I mostly used my 24-105 lens. But as it dropped and moved slightly north (to the right), away from Whitney, we hopped in the car and raced about a mile south, to the location I’d chosen knowing that Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would align perfectly with Whitney as it dropped below the peaks. Most of my images from this location were captured with my 100-400 lens.

I manually focused on the comet’s head, or on a nearby relatively bright star, then checked my focus after each image. The scene continued darkening as I shot, and to avoid too much star motion I increased my ISO rather than extending my shutter speed.

As I photographed, I could barely contain my excitement at the image previews on my cameras’ LCD screens. Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and its long tail were clearly visible to my eyes, but the cameras’ ability to accumulate light made it much brighter than what we saw. The image I share today is one of my final images of the night. Even with a shutter speed of only 5 seconds, at a focal length of right around 200mm, if you look closely you’ll still see a little star motion.

My giddiness persisted on the drive back to Lone Pine and into our very nice (and hard earned) dinner. When our server expressed interest in the comet, I went out to the car and grabbed my camera to share my images with her. Whether or not the enthusiasm she showed was genuine, she received a generous tip for indulging me. And even though I usually wait until I’m home to process my images on my large monitor, I couldn’t help staying up well past lights-out to process this one image, just to reassure myself that I hadn’t messed something up (focus is always my biggest concern during a night shoot).

And finally…

FYI, neither Rob nor I became spies, but we have stayed in touch over the years. In fact, the original plan was for him to join me on this adventure, but circumstances interfered and he had to stay home. But we still have hopes for the next comet, which could be years away, or as soon as late this month….

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

My Comet History

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Every. Single. Thing.

Posted on August 23, 2024

Sunset Reflection, North Lake, Eastern Sierra (2008)

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

Canon 17-40 f/4 L

10 seconds

F/11

ISO 200

A few days ago, while browsing old images looking for something else, I came upon this one from a solitary sunset visit to North Lake above Bishop almost 16 years ago. It’s a great reminder to appreciate my past efforts, and to not forget that, even though some images from my distant photography past evoke a “What was I thinking?” face palm, I really did have an idea of what I was doing—even if my execution wasn’t always perfect.

One of the earliest lessons I learned on this path to where I am as a photographer today, a lesson I work hard to impart on my workshop students, is the photographer’s responsibility for each square inch (and pixel) in the frame. Not just the beautiful elements, but everything else as well. Every. Single. Thing.

It’s always heartening to see the genesis of that approach in my older images. Rather than just framing and clicking the obvious, I can see signs that I took the time and effort to assemble the best possible image. That assembly process might start weeks or months before I arrive (planning for a moonrise, fall color, the Milky Way, and so on), or it could simply be a matter of making the best of whatever situation I’m presented when I arrive.

Either way, once it’s time to take out the camera and get to work, before clicking the shutter I try to make a point of surveying the scene to identify its most compelling elements. Once I’m comfortable with the possibilities, I position myself to create the ideal relationships between the various elements, then frame the scene to eliminate distractions, and finally, choose the exposure variables that achieve the motion, depth, and light that create the effect I want. And while my execution still isn’t always perfect (and will always have room for improvement), I think this image in particular illustrates my assembly process.

I’ve been visiting North Lake in autumn for nearly 20 years, both on my own and in my workshops. Most of these visits come at sunrise, but this time, by myself in Bishop with an evening between workshops, I decided to explore some of my favorite spots near the top of Bishop Creek Canyon. I pulled into North Lake and was surprised to find it completely devoid of photographers—a refreshing difference from the customary autumn sunrise photographer crowds that usually outnumber the mosquitos.

Early enough to anticipate the sunset conditions and plan my composition, I was especially excited by the western sky above the peaks, which was smeared with broken clouds that just might (fingers crossed) color up when the sun’s last rays slipped through. Without the swarm of photographers I was accustomed to here, I took full advantage of the freedom to roam the lakeshore in search of a composition that would do the (potential) sunset justice. Rather than simply settle for the standard version of this inherently beautiful scene that might be further enhanced by a nice sunset, I wanted a composition that assembled the best of the scene’s various features—colorful sunset sky, serrated peaks, golden aspen, crisp reflection, small granite boulders—into coherent relationships that allowed everything to work together that might be a little different.

I eventually rock-hopped to this mini granite archipelago near the lake’s outlet and found what I was looking for. Since I’d always gone horizontal at North Lake to feature the arc of peaks framing the aspen-lined lake, this time I decided to emphasize the foreground rocks and reflection with a vertical composition. (I’ve since had great success with vertical frames at North Lake, but this is the one that really opened my eyes to the vertical possibilities here—see the image on the right from two years later.)

First I positioned myself so the line of small granite rocks formed a diagonal along the bottom half of the frame, enhancing the scene’s illusion of depth. Next, I lowered my camera (on a tripod, of course) to minimize the empty patch of lake between the rocks and reflection.

As much as I like my images to have uncluttered borders, in nature it’s often impossible to avoid cutting something off, or to prevent a small piece of an object outside the frame from jutting in (like a rock or branch). In this case, from my chosen location, including the foreground rocks I considered essential meant cutting off other rocks. When I run into these situations where a clean border is impossible, I at least need to make my border choice very deliberate. In this case, I took care to include all of the rocks at the bottom, but chose to cut the rocks on the left boldly, right down the middle, so they don’t look like an afterthought (or a never-thought).

As much as I liked the mountain, aspen, and sunset parts of the reflection, I found the reflection of the sky above the colorful clouds pretty dull. So I dialed my polarizer just enough to erase the bland part and reveal the (more interesting) submerged rocks near the lakeshore, taking care not to lose the best part of the reflection.

Of course, including the nearby rocks added another layer of complication: ensuring that everything, from the foreground rocks to the distant mountains, was sharp. Because every image has only one perfectly sharp plane of focus, in a scene like this, finding the right focus point and f-stop is essential.

Of the various techniques photographers apply to ensure proper focus, Hyperfocal focusing is the most reliable. Hyperfocal focusing determines the combination of focal length, f-stop, sensor size, and focus point that ensures the ideal position and depth of the frame’s zone of “acceptable” sharpness. Since identifying the precise hyperfocal point (the point of maximum depth of field) requires plugging variables into a chart (the old fashioned way) or smartphone app (the smart way), many photographers foolishly decide it’s not worth the effort. But, like most things that start out difficult, regularly applying hyperfocal focus technique soon reveals its underlying simplicity. (I rarely have to check my app anymore, usually relying instead on experience-based seat-of-the-pants hyperfocal focusing.)

Today, with my mirrorless cameras, I am able to precisely position my focus point using a magnified viewfinder view, and I completely trust my camera’s autofocus. But because the evening of this image was back in my DSLR days, when I never completely trusted autofocus when the margin for error was small, I know I manually focused it.

So where did I focus? Well, even though I no longer remember, I’d bet money that it was on first small rock beyond the trio of rocks at the bottom. I think that because, 1) that just seems like where I’d instinctively focus, and 2) my hyperfocal app tells me that the hyperfocal distance for this image’s settings (thank you EXIF data) was a little less than 3 feet, and that rock was about 3 feet away. Since close scrutiny at 100 percent confirms that the image is sharp from front to back, I’m pretty confident that’s where I focused.

The final piece of the puzzle was exposure. At the time I was shooting with a dynamic range limited (compared to my Sony Alpha cameras) Canon 1DSIII, so I’m pretty sure I used a 3-stop soft graduated neutral density filter to subdue the bright sky. (FYI, I no longer carry a GND.) This always requires a little extra work in Photoshop because I hate, hate, hate the GND transition’s darkening effect on the landscape immediately beneath the sky, which always requires a little dodging and burning to eliminate.

There really was a lot going on in this scene, and I’m pretty pleased that I was able to make everything work together. Of course that doesn’t always happen, but I find the more I’m able to consider every single thing in a scene, the happier I am with my results.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Image Building

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Canon 1DS III, Eastern Sierra, fall color, North Lake, Photography, reflection Tagged: autumn, Eastern Sierra, fall color, nature photography, North Lake, reflection

A Peek Behind the Curtain

Posted on October 24, 2023

A particular highlight of my annual Eastern Sierra photo workshop is our sunrise shoot at North Lake. Made famous as the default desktop image for macOS High Sierra, North Lake is a small lake in the shadow of snow-capped Eastern Sierra peaks, near the top of Bishop Creek Canyon a little west of Bishop. It’s encircled by aspen, and reflections in its sheltered bowl are quite common. More than once my groups have been fortunate enough to enjoy a light dusting of snow along the lakeshore.

Depending on the conditions, we’ll stay at North Lake for at least an hour—often longer. But the photography isn’t over when we do finally leave, because just down the mountain from the lake are some of my favorite Sierra fall color spots. In the two miles between North Lake and Lake Sabrina (Pro Tip: it’s pronounced with a long “i,” like China) at the top of the canyon, we can choose between mountain vistas, dense aspen groves, views of aspen lined Bishop Creek, and several small reflective ponds also accented by aspen.

The conditions determine our stops. When it’s cloudy (low contrast light), we can shoot anywhere for hours; when the sky is clear, the best photography is done before the sun arrives, forcing me to be a little more selective to get the most of our limited time.

This year, with few clouds and morning light rapidly descending the mountainsides, after North Lake I took my group to the deep shade at the canyon’s bottom, stopping first to photograph the gold and (a few) red aspen framing Bishop Creek, then moving a half-mile or so upstream for reflections in a couple of pools formed by wide spots in the creek. There’s so much to photograph at both of these locations that the group always scatters quickly—when that happens, I know we’ll enjoy a wonderful variety of images at the next workshop image review.

Always on the lookout for something new, familiar locations like Bishop Creek kick-in my natural urge to explore. But when I lead a workshop, I’m well aware that no one pays their hard earned money only to spend their days (and nights) following the leader to places he’s never been. So, despite the obvious beauty here, I’m usually content to simply step back and take it all in.

Nevertheless, I try not to let that inhibit my explorer’s mindset. As I walk about checking on my workshop students, or simply while taking in the surroundings, I often find myself silently asking, “I wonder what’s over there.” Though circumstances don’t usually allow me to actually find out on that visit, I mentally file the spot away for a time when no one depends on me. But every once in a while an opportunity to explore surprises me in the moment.

I knew the sun this morning would reach us at around 9:00 a.m., so around 8:30 I started making my way around to everyone to let them know that we had about 30 more quality minutes before we’ll head back down the mountain for breakfast. The creek here parallels the road, with all the standard photo spots between the road and the creek. While waiting for people to wrap up after I made my rounds, I thought I might have just enough time to find out what’s on the other side of the creek and crossed the bridge, where I found a barely discernible path into the woods.

This was just a quick reconnoissance mission, so my camera bag remained in the car. At first the path was so overgrown that in spots I had trouble following it, but after about 50 yards it opened into a sublime fern garden, walled by aspen and sprinkled with golden leaves. I knew instantly it was too small and fragile to bring a group to, but I also knew I had to photograph it. So I raced back to my car, grabbed my camera bag and tripod, and was back in business in just a few minutes.

I only had about 5 minutes to photograph, but that was enough to drop low, compose wide, meter and focus, and capture a half-dozen or so horizontal and vertical frames. The treetops were already getting washed out by the advancing sun, so I emphasized the foreground ferns with all my compositions, cutting off the sunlit parts of the aspen—an effect that creates the illusion of infinite depth in this relatively compact space.

When I first arrived back here, the dense forest on all sides made me feel completely isolated. But as I worked my scene, I became aware of people in my group laughing and chatting as they worked their own scenes, and realized that I was only a few feet from the creek. That got me thinking about all the intimate beauty underlying the larger scenes that first draw our attention. In this natural garden this morning, it felt as if I’d peeked behind a curtain and discovered an entirely new world.

This is a reminder to me that even the most in-your-face beauty is comprised of easily overlooked subtleties, and that no matter how beautiful the first thing you see in a scene, there’s always more there. The best photography doesn’t show us the world we already know, it pulls back a curtain to expand our understanding of the unseen world.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Off the Beaten Path

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: aspen, aurora, Eastern Sierra, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM, Sony a7R V Tagged: aspen, autumn, Eastern Sierra, fall color, nature photography

Older Than History

Posted on October 17, 2023

Last Light on the Bristlecones, Schulman Grove, White Mountains (California)

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 100

f/16

1/4 seconds

Ask people to name California’s state tree and I’m afraid most would go strait to the palm tree—which isn’t even native to the Golden State. And though the correct answer is the redwood, those of us born and raised in California might argue that the stately oaks that dominate the foothills throughout most of the state conjure the strongest feelings of home.

But without diminishing the other trees, let me give our ancient bristlecone pines some much deserved love. Lacking the ubiquity of California’s palms and oaks, and the mind-boggling stature of our redwoods, bristlecones are largely unknown to California residents and visitors alike. But, not only do these twisting, gnarled trees look specifically designed for photography, for me it’s their fascinating natural history that truly sets bristlecones apart.

All varieties of bristlecone pines can live for millennia, but today I’m referring specifically to the Great Basin bristlecones, which have earned the distinction of being among the oldest living organisms on Earth. Earned being the operative word there.

Slow growth, a shallow and extensively branched root system, dense wood, and extreme drought tolerance contribute to the bristlecone pine’s longevity. How old are they? Well, many predate Christ, and at 4850 years old, the Methuselah tree (whose location somewhere near the Schulman Grove of the Inyo National Forest is a closely guarded secret) had already lived more than three centuries when the Egyptians broke ground on the first pyramid.

My favorite fact about these trees is that the more harsh a bristlecone pine’s environment, the longer it lives—a wonderful metaphor for perseverance that might bolster anyone battling the headwinds of life. Also found at the most extreme elevations of Nevada and Utah, Great Basin bristlecones especially thrive in the high elevation (low oxygen), extremely arid and rocky conditions above 9500 feet in the rain-shadowed White Mountains, just across the Owens Valley from the Sierra Nevada.

In the oldest bristlecones the majority of the wood is actually dead, with only a small area of living tissue connecting the roots to a few surviving branches. Having a relatively small amount of living tissue allows a bristlecone to sustain itself with minimal resources, while the extreme density of its dead wood serves as armor against harsh conditions. And once a bristlecone pine does die, with wood so hard and roots so robust, they can remain standing for centuries.

I visit these amazing trees each autumn in my Eastern Sierra Fall Color workshop. And though they’re technically not in the Eastern Sierra (but do provide spectacular views of it), and are completely devoid of fall color, so far no one has complained. On each visit I send my group up the Schulman Grove Discovery Trail loop, a short (one mile) hike starting at 10,000 feet with a 300 foot elevation gain that tests the fitness of all who attempt it. Compensation for all this effort is the opportunity to stroll among dozens of truly photogenic trees, each with its own unique character, that predate most human history.

All of the climbing happens in the first half mile—just about the time everyone is ready to turn around (or string-up the leader on the nearest bristlecone), the trail levels, then mercifully drops for the remainder of the hike. I’ve been doing this hike for more than 15 years, sometimes multiple times in a year, and if I’ve learned nothing else, I know to give everyone enough time to actually enjoy it.

It helps that most of the best trees are on the first half of the trail, as are 2 or 3 strategically placed benches. The ultimate payoff is a pair of striking bristlecones standing by themselves on a west-facing slope a little beyond the trail’s halfway point and just after the trail starts descending.

Because we start hiking about 90 minutes before sunset, and there’s no chance anyone will get lost, I let each person go at whatever pace makes them comfortable. And before setting everyone free, I remind them that there’s plenty of time to stop and take pictures (or pretend to take pictures) whenever they need to catch their breath.

I’ve visited these trees so many times, I rarely photograph them anymore—and when I do, few shots ever get processed. But as I got people started this year, I suspected things might be different because we’d been gifted with nice clouds—a welcome sight indeed.

I always let everyone in my group start up the trail before me, then wait at least 5 more minutes, so I can check on each person after they’ve had a a few minutes to experience the grade and thin air. In more than a few prior years I’ve had to race to the target trees, drop my gear, and double-back to check-on/assist others who might be struggling, but that wasn’t necessary this year—everyone made it to the trees by sunset without any trouble, albeit some much sooner than others.

When I first started coming here there were no posted requirements to stay on the trail, and photographers didn’t hesitate to clamor about the base of the trees in search of the best angle. But all this activity threatened to damage the trees’ shallow roots, so in recent years signs have been posted making it very clear not to leave the trail.

This new edict has actually made my job easier, as I no longer need to choreograph an assortment of photographers with conflicting agendas (even just one person scrambling up to the trees can ruin everyone else’s frames). Now we all just line up along the trail on either side of the trees, then shuffle positions when it’s time to change angles.