Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

A Moving Experience

Posted on December 18, 2025

I’ve been photographing Kilauea’s eruptions, in many forms, for 15 years, but never anything close to the spectacular display my workshop group and I witnessed in September. It wouldn’t be hyperbole to say that this was one of the most memorable experiences of my life. (I’ve said that about Kilauea eruptions before, but each time I say it, Kilauea seems to say, “Oh yeah? Hold my Mai Tai.”)

As a photographer who obsesses about controlling every pixel in my frame, and who (semi-) jokingly asserts that I don’t photograph anything that moves, there was a lot going on atop Kilauea this morning. Anybody up there with a camera could have snapped a few frames and captured something worthy of sharing, but whether it’s a vivid sunset, dancing aurora, or fountaining lava, serious photographers need to separate themselves from the “anybodys” and pay attention to the little things easily overlooked in the thrill of the moment. This morning on Kilauea, with an obvious focal point and empty foreground, the biggest (and most easily overlooked) challenge was the constant motion in the scene.

Let’s review: Photography is the futile attempt to convey a dynamic world using a static medium. Though that’s literally impossible, what is possible is conveying the illusion of motion—that is, capturing the scene in a way that enables viewers to infer its motion. Finding the shutter speed that freezes a moving subject in place or renders it with some degree of motion blur, while getting the light perfect, is a basic photography skill that simply requires mastery of the three exposure variables.

Motion in a landscape image can take many forms, some easier to address than others. Though waterfalls and whitewater rapids may move fast, at least they stay in one place while the water moves within. But other natural subjects move more unpredictably. Lightning, for example, comes and goes so suddenly, I never even consider using my own reflex/reaction skills to freeze its transient existence—I simply connect my Lightning Trigger, aim my camera, and wait for my trigger and camera to do the work. Ocean waves, while less organized than whitewater, are at least predictable enough to anticipate and time—that said, I generally prefer to simply shoot a series of wave images with varied timing and motion effects, then pick my favorite later.

Somewhere between lightning and waves on the predictable/random continuum are atmospheric phenomena like the northern lights, and regular old clouds. Though they’re in constant (seemingly) random motion, that motion is usually more my speed—slow enough to anticipate and adjust my composition and exposure without feeling too rushed.

But it’s not just about how you render the motion—another complicating factor is paying attention to subjects that don’t stay put: a composition that was perfect seconds ago could be completely out of whack right now. Which happens to be the biggest challenge this memorable morning in Hawaii.

Now might be a good time to mention that part of my desire to control my entire frame makes me especially obsessive about both the borders of my images, as well as the relationships of the elements in my frame that draw the eye. That means trying to avoid cutting strong elements on the edges of my frame, creating a sense of connection and balance between strong visual elements, and avoiding (or minimizing) visual elements that compete with my subject or subjects. So when my subjects are in motion, as they were on Kilauea this morning, I need to monitor and adjust continuously.

Arriving with my workshop group several hours before sunrise, the total darkness meant I only had to contend with 800-foot explosive lava fountains and the lava rivers surrounded by a sea of black. The lava fountains, while exploding violently and pretty much non-stop, were far enough away that they seemed to be moving in slow motion. The lava rivers, though constantly ebbing, flowing, and changing course, moved slowly enough to be relatively manageable too.

My goal was to freeze the lava’s motion in place, and soon I settled on a shutter speed I was confident would do that even at my longest focal length. With the unchanging light (dark) and a shutter speed I knew was fine, it wasn’t long before I found a rhythm, complementing compositions centered on the “stationary” lava fountain (the lava was moving, but the fountain stayed in one place) with the current position of the flowing lava rivers, then timing my shutter click for when the latest fountain peaked or spread most dramatically. I worked this way for a couple of hours, mostly using my 100-400 and 1.4X teleconverter, zooming in and out and switching between horizontal and vertical compositions.

Things changed when sunrise started painting the sky pink and revealing a previously unseen plume of billowing smoke, vapor, and tephra. Suddenly, my priorities switched to wide angle to capture all the additional beauty brought by the increasing light. And just as suddenly, I had to adjust the compositional imperatives underlying my prior rhythm, now factoring into the mix the wind-whipped smoky plume tower that expanded and shifted by the second, the pink clouds, and even new detail on the caldera floor. And with the rapidly brightening sky, an exposure that worked 30 seconds ago, now blew out the sunlit highlights. Not only that, I knew the plume’s gorgeous warm light was peaking and would only last for another minute or two, further ratcheting up my urgency.

Switching to my 16-35 lens, I framed up a completely new composition and adjusted to a new combination of motion considerations. In this case, including the lava and rising plume were no-brainers, but the goal should be more than simply taking a picture that includes both—everything needs to work together to create something that stands out from the thousands of other images captured at the caldera that morning.

Managing all of a scene’s moving parts is what good photographers are supposed to do. That said, I notice—both in my workshops and online—that many photographers seem so focused on their scene’s one or two most prominent features that they lose track of still important secondary and tertiary elements. And when one or more of those less essential elements is moving, for example waves or clouds, their new position is easily overlooked, leading to random and often less than ideal results.

In this case, while keeping an eye on the active lava as I’d done all morning, I suddenly also needed to keep track of an expanding smoke plume that was in constant motion, illuminated by ever-changing sunlight. While not especially difficult if you’re paying attention, this doesn’t just happen automatically (and I have the pictures to prove it).

Keeping my borders as clean as possible became a prime concern, so I kept a constant eye on the shifting smoke plume to avoid cutting it off. On the left and top I just needed to keep the plume off the borders of my frame; since the wind had stretched the smoke far beyond any reasonable frame on the right side, I also needed to find the best place to cut that side with the right border. And as with my rapidly changing exposure, a composition that worked one second might need to be completely adjusted the next.

I tried to go just wide enough on the right to include all of the main (and most dramatic!) vertical section of the sunlit plume, and on the right went just a little wider than that to include that one small splash light—any farther right would have shrunk my subjects while adding nothing more than a homogenous horizontal band of brownish-gray smoke.

The result of all these machinations is this wide vertical frame that includes the fountaining and flowing lava that was the star of the show that morning, plus all of the sunlit portion of the beautiful smoke plume. Accomplishing this was not rocket science, and I’m not pretending to be special for achieving it. But I do think photographers often fall down when they get so caught up in the majesty of the moment that they fail to take that one extra step to account for the scene’s motion, and the importance of those subtle changes from one frame to the next.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

World in Motion

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM II, Sony Alpha 1, volcano Tagged: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, lava, nature photography, volcano

Kilauea Eruption Episode 33, Part 2: Grand Finale

Posted on September 29, 2025

Fountain of Fire, Kilauea Eruption, Hawaii

Sony a7R V

Sony 100-400 GM

ISO 400

f/5.6

1/125 second

For the full context of my experience with Kilauea eruptions in general, and the events leading up to the fountaining portion of this episode (33), check out my prior blog post: Kilauea Eruption Episode 33, Part 1: So You’re Telling Me There’s a Chance…

The euphoria of our (very) early Thursday morning Kilauea eruption shoot powered my workshop group through the day and into Thursday night. Since we hadn’t made it back to the hotel until 4:00 a.m., I pulled the plug on our sunrise shoot (with zero objections), and the group didn’t gather again until our 1:00 p.m. image review session. It turns out many were so excited by the eruption experience, they opted for downloading and processing over sleep, but the few eruption images we did see definitely turbocharged the eruption enthusiasm.

The discussion during the afternoon meeting centered around whether the fountaining we saw was Kilauea’s new normal, or whether there might be more to come. My inherent optimism went straight to the fact that the prior episode (episode 32, in early September) had delivered the second greatest volume of lava to the caldera floor of all the episodes —the most of 2025 so far. And the latest USGS report said that continuing inflation at the summit meant more was coming. Yay.

The pessimist in me, that annoying little voice that keeps reminding me of the times Mother Nature has thrown cold water on high hopes, kept reminding me of the signs that the reliable eruption sequence that started in December 2024 might be flagging: the fountain height of recent eruptions had decreased significantly from its 1000+ foot peak; the gap separating each fountaining phase was increasing; and most significantly (in my mind), live webcams focused on the eruption’s vents showed that the activity we’d photographed the prior night had completely died—only smoke was visible where we had once seen bubbling, flowing lava.

Shortly after the image review session, we departed for the workshop’s sunset shoot at my favorite beach on the Puna Coast. That evening’s spectacular sunset pushed the eruption buzz to the background, and in a way felt like a fitting wrap-up to a fantastic workshop. We did have one more sunrise shoot planned, but I think everyone felt like it would be anticlimactic following all we’d photographed in the workshop so far. In fact, with flights to catch and coming off a night with very little sleep, when I suggested that we stay in Hilo and stick to the sunrise plan even if the eruption resumed during the night, the agreement was unanimous—we’d already had a great volcano shoot that would be tough to beat. (We’d already been up to Kilauea twice, so I also suggested that anyone who changed their mind should feel free to go up on their own if the eruption started.)

That plan lasted until 3:30 a.m. One of the workshop participants (who had his office manager in Ohio, where midnight in Hawaii is 6 a.m., monitoring the Kilauea webcams and reporting any changes) messaged the group, “It’s fountaining!” I was sound asleep, but the messaging frenzy that followed quickly roused me enough to grab my phone and check the webcam. I instantly knew the sunrise plan was out the window and we were going back to Kilauea, sleep be damned. When he said fountaining, he meant FOUNTAINING!!!

This fountaining was on an entirely different scale from what we’d seen the prior night, or even from anything I’d ever seen—like someone had kicked a giant sprinkler head on the caldera floor. (I learned later that it was the highest fountaining since early July.) Almost all of the group was wide awake and on the road in 20 minutes.

Even though we arrived before 5:00 a.m., a little more than an hour after the fountaining began, the park was much more crowded than we’d seen the previous night. We found parking, but just barely, and I knew the way cars were streaming into the park the open spaces wouldn’t last long.

Because of the crowds, we’d implemented an “every car for itself plan,” each doing its own thing while staying in contact. My car started at Kilauea Overlook, but found the view, while very close, was partially obscured behind the caldera rim. So we quickly doubled back to the Wahinekapu Steaming Bluff (steam vents), for the best combination of direct view to the fountaining vents, and fast access. There we reconnected with most of the rest of the group.

The view to the fountaining vents from the Wahinekapu is about 2 miles—our other option was the closer vantage point at Keanakako’i Overlook, on the other side of the caldera (where I shot the 2023 eruption). This is about 1.25 miles from the fountains, but also required a 15 minute drive followed by a 1 mile walk, and I knew that even if we found parking there (far from a sure thing), it would probably be starting to get light by the time we got our eyes on the eruption. Plus, having shot the eruption from Wahinekapu already, I knew we’d be close enough that 400mm would be plenty long enough.

I’m so glad we took the path of least resistance and stayed at Wahinekapu. Even though my brother Jay (who was assisting me in this workshop) and I had a very small window to shoot before we needed to head back to Hilo to catch our flight home, the timing of the eruption and our arrival couldn’t have been better. We started with nearly an hour of complete darkness, allowing exposures that froze the fountains without blowing out the highlights (overexposing the lava) to create the virtually black background that I think makes the most dramatic lava images. Following the complete darkness, we photographed through the slow transition into a beautiful sunrise. Finally, as the day brightened, we enjoyed about a half hour of the eruption’s towering plume warmed by lava-light from below, and low sunlight from above. Absolutely spectacular.

When I first photographed lava in 2016, I was learning on the fly. At night, standard histogram rules don’t apply to lava because a properly exposed frame will be almost completely smashed agains the left side (with much cut off), and often, especially on wider shots, with just few small highlight blips on the far right. Basically, job-one is to make the lava as bright as possible without blowing it out. And job 1a is to do that using a shutter speed that freezes the lava’s motion (unless motion blur is your objective). And finally, you really should do this using the best (lowest) possible ISO.

The mistake people make for any kind of motion blur, and I’ve heard a lot of “best shutter speed for Kilauea’s lava fountains” advice, is to assume that there’s one ideal shutter speed for freezing the lava fountains. There isn’t. Just as with flowing water, the shutter speed that freezes a lava fountain is a function of several factors: the speed at which the lava is moving—the higher the fountain, the faster the lava will be moving when it reaches the ground, the distance to the fountain, and the focal length.

Back in 2016 I started with extremely high ISOs to maximize my shutter speed, but have gradually, through trial and error, dropped both my ISO and decreased my shutter speeds for my lava images. At night, since depth of field is usually no concern, for most of my long telephoto shots using my 100-400, I now just shoot wide open, at f/5.6 for that lens. My exposure trial and error process involves taking a shot at a certain focal length, verifying that the lava is close to maximum brightness without blowing out, then magnifying the image in my viewfinder (or LCD) to confirm that there’s no motion blur in the lava fountain (make sure you check the lowest lava blobs, as they’ll be moving fastest). If that works, I lower my ISO and increase my shutter speed further, until I find the threshold where blur is discernible. Then, for a just-to-be-safe cushion, I bump my ISO and shutter speed back up to just slightly more than the prior settings (that I thought froze the lava).

I had to do this for every significant change in focal length, but it wasn’t long before I became pretty comfortable with my settings. And by the time this Friday morning lava fountaining started—having done it in 2016, 2022, 2023, and earlier that week—I was feeling so comfortable with my exposure settings that it was no longer a distraction. In fact, I was varying my focal length so frequently and clicking so fast, to simplify the process I just kept my exposure settings in the range I knew would work all the way out to 400mm. I was fine with this because a very satisfactory ISO 400 gave me a shutter speed in the 1/100 to 1/200 second range that I knew worked.

So bottom line? In total darkness, standing 2 miles away, at 400mm I was perfectly comfortable with f/5.6, ISO 400, and 1/100. But I hope you can see that my exposure settings probably won’t work for you if you’re much closer than 2 miles, and might be overkill if you’re farther away. In other words, I strongly encourage anyone who wants to photograph fountaining lava to apply my process, not my settings. (And there are many people with far more experience photographing lava than I have, so feel free to defer to them if their results confirm that they know what they’re talking about.)

This experience, the final shoot of my 2025 Hawaii Big Island workshop, wasn’t just the grand finale for this workshop, it was the grand finale of 15 years of Hawaii workshops. As I pare down my workshop schedule and ease (slowly) toward retirement, I decided a few months ago that this would be my final Hawaii workshop. Not because I don’t enjoy it (I do!), or because it no longer fills (it does!), but simply because I had better reasons to keep other workshops. Just as my final Grand Canyon raft trip was gifted with a beautiful, albeit less dramatic, crescent moon for our final sunrise, I can’t imagine a better Hawaii memory to go out on.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Kilauea Memories (2010-2025)

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Hawaii, Kilauea, Photography, Sony 100-400 GM, Sony a7RIV, volcano Tagged: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, lava, nature photography, volcano

Kilauea Eruption Episode 33, Part 1: So You’re Telling Me There’s a Chance…

Posted on September 24, 2025

One out of a million…

One of the great motivators for a nature photographer is the potential for the unexpected. As much as I love planning my photo shoots, especially when things come together exactly as hoped, the euphoria of the unexpected feels like photography’s greatest reward.

Some natural phenomena can be predicted with surgical precision—events like a rising or setting sun or moon, a total solar eclipse, the moonbow that materializes every spring full moon at the base of Yosemite Falls, and the sunset light that colors Horsetail Fall in late February—with the only variable being whether or not the clouds will cooperate enough to allow us to view the show.

I love those reliable phenomena and have made my living scheduling photo workshops to share them with others. But I also have a few workshops scheduled around the hope of something spectacular—a high risk, high reward roll of the dice that can only be timed to provide the best chance of success. In this category I include the Iceland aurora workshops Don Smith and I do each year, my Grand Canyon monsoon workshops where we cross our fingers for lightning and rainbows, and my latest obsession, chasing supercells and tornadoes across the US and Canadian plains.

But let me submit a third category: those phenomena where there’s absolutely nothing strategic about the timing, and when it occurs, it feels like a gift from Heaven. I guess that could describe any random sunset, rainbow, or unexpected snowfall, but I’m thinking more about those one-out-of-a million phenomena that are so spectacular and rare, for many they’re a once in a lifetime event. Like an erupting volcano.

My personal volcano history

I’ve been visiting Hawaii’s Big Island every (non-Covid) September since 2010. Through 2017, the lava lake in Halemaʻumaʻu on Kilauea’s summit bubbled away 24/7, allowing each of my workshop groups to view and photograph beneath the Milky Way. This was so reliable, I simply took lava’s nightly glow for granted. Until 2016 I never saw actually the lava itself, just its rising smoke and vapor plume during the day, and the lava’s orange radiance illuminating the caldera walls after dark. But in 2016 the lava lake rose to the top of Halemaʻumaʻu and overflowed onto the caldera floor, and my group and I were gifted with the rare opportunity to view bubbling, exploding lava. Then in 2017 everything was back to normal, and my group returned to photographing the glow (and me to taking the eruption for granted).

But in a frustrating exhibition of Mother Nature’s fickle whims, in 2018 she reminded me to never take her for granted, and completely shut off the summit eruption the week before my workshop. Of course there’s lots of other stuff to photograph on the Big Island (my favorite Hawaiian island), but it’s pretty hard to top a volcanic eruption.

Since 2018, Kilauea has been mostly quiet, with a handful of relatively minor eruptions each year, most measured in hours or days, arriving with very short notice, and vanishing just as suddenly. In other words, impossible to plan a workshop around, and rare enough to never be expected.

My groups got nothing from the volcano in 2018, 2019, and 2021 (2020 was lost to Covid). Then in 2022, my workshop group and I were fortunate enough to get a long distance view of an eruption and the Milky Way from a brand new location. And in 2023 we hit the jackpot when a very active eruption started the day before my workshop, and ended the day after. For that one, I got to photograph numerous small fountains and lava rivers across a wide area of the caldera floor three different times, and my group enjoyed the same show twice. Then in 2024, Kilauea was quiet again.

I knew that Kilauea’s eruption history meant that the next one could be tomorrow, or years away. Or never. But in December of 2024, a whole new kind of eruption started on Kilauea. Instead of smaller fountains spreading across the caldera as we’d seen in 2023, this one was limited to one or two massive fountains. And instead of the recent one-and-done eruptions that would last for days or (occasionally) weeks, this new eruption came in short and sweet bursts separated by days. The first few lasted longer, up to 8 days, but after a while this latest eruption established a fairly regular routine, coming every week or so and lasting less than a day.

The fountaining in some of these episodes exceeded 1000 feet (a height I struggled to imagine, despite the many pictures and videos shared online), with most reaching at least 300 feet—far higher than anything I’d seen before, including in 2023.

Finally, we get to this image

(That’s a lot of context for just one image, so thanks for sticking with me.)

Since I scheduled the 2025 Hawaii workshop in the summer of 2024, I added it with no expectations of photographing an eruption. I simply knew any eruption, while always possible, was quite unlikely. Of course Hawaii has plenty to photograph without an erupting volcano, but a person can dream….

When the current eruption started late last year, nothing in recent history gave hope that it would last long enough to still be going by the time my workshop came around. With 10 months to go, my hope meter stayed pegged on zero. But as the volcano settled into its once-a-week routine and the months clicked past with little change in that pattern, I started to notice a slight quiver in the meter’s needle.

But as we all know, Mother Nature toys with hope. No sooner had my meter shown signs of life, the reliable one-week span between eruptions started stretching out to 10-14 days, the episode duration dropped to less than 12 hours, and the fountain heights dropped well below 500 feet. By the time episode 32 came and went in early September, I was down to hoping my workshop group would be lucky enough that the 12-hour or less span of the next episode (if there was a next episode), would fall sometime in the workshop’s 4 1/2 days. Not great odds, but to be safe, a few weeks before the workshop I e-mailed my group explaining our poor odds, but also reassuring them that if any eruption did happen during the workshop, we’d drop all other plans and I’d do everything in my power get us up to Kilauea to view it, regardless of the hour.

But in the secret recesses of my mind, despite my overwhelming desire to see and share this unprecedented sight, the possibility (no matter how small) that I might be responsible for navigating a dozen photographers and 3 vehicles through the mayhem reported to accompany every prior episode—gridlock and hours just getting into the park, no parking once we get in, and limited viewing space—was daunting at best. Combine that with the fact that I obsess about getting my eyes on a scene before guiding a group to it—not only did I not have any experience with the best viewing locations for this eruption (each eruption happens at a different location in or near the crater), if it did happen during the workshop, I’d be learning on the fly, with my group depending on me.

I did as much research and preparation as possible from 2600 miles away, scouring the internet, reaching out to others I knew who had viewed prior episodes, and practically memorizing the viewing instructions on the NPS Hawaii Volcanoes website. But I knew all this planning would be of little use if we made the 45 minute drive from our Hilo hotel to the park and found it teeming with double-parked photographers and gawking tourists.

Then, just a few days before the workshop, the USGS posted an eruption forecast stating that the earliest the next episode would start would be September 19, and possibly later if summit inflation (the amount of magma in the subterranean chamber) decreases. Since my workshop wraps up following the sunrise shoot on September 19, I knew we’d almost certainly miss it. A disappointment for sure, but also a significant stress reliever.

On my pre-workshop scouting visit, I learned that the vent of the eruption had been glowing the last couple of nights, a sign that the magma chamber was filling. With that information I realized there might be an opportunity to give my group a caldera night shoot for the first time since 2017. Not only that, as I scouted the views to the current eruption vents, I realized that I’d be able to align the caldera’s glow with the Milky Way, just like the olden days. Even without an eruption, things were looking up.

On Tuesday, our second night, I took the group to the caldera for sunset, and we stayed for a magnificent Milky Way shoot beneath a spectacularly (and unusually) clear sky. In fact, unlike all the prior Kilauea Milky Way shoots, where we just photographed a glowing hole at the bottom of a featureless caldera floor, subsequent eruptions (and especially the current one) had raised the caldera floor from 100 to 300+ feet, and replaced the dull rocks and shrubs with brand new beautifully textured lava. And the glow now emanated from a discernible volcanic cone that at times during our shoot emitted visible splashes of lava.

I went to bed that night overjoyed to have given my group an actual active volcano experience. And then I woke Wednesday morning. Checking the USGS Kilauea status update, I did a double-take. The earlier September 19 – 23 episode 33 forecast had been revised to indicate that an eruption was imminent, and could start any time from September 17 (today!) to 19. Whoa.

Along with the euphoria that we might indeed get to witness an actual fountaining eruption came the prior anxiety of not knowing exactly how I’d navigate it. So I devised a plan. Knowing that we’d all been up to the volcano the prior day, I decided that if the eruption does start, we’d drop everything and immediately beeline to Kilauea as a group, in no more than 3 vehicles (there were 14 of us, including me and my brother Jay). Once there, we’d do our best to stay together, but if it was too crowded and unmanageable, each car would have full autonomy to go where its occupants wanted to go, and to stay as long as they wanted. If that happened, we’d still keep in constant contact via our workshop WhatsApp group (which we’d already been using all week), and share any insights we learned about parking or vantage points. With a plan in place, we went about the day’s workshop plans (Akaka Falls and Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden), keeping a constant eye on the USGS eruption webcams and status updates.

Nothing had happened by the end of the day, so before sending everyone off for the evening, I checked to see who wanted to be awakened if the eruption started overnight, and found that all but three were up for an overnight adventure.

At 11:30 p.m. I’d already been asleep for a couple of hours when my phone started lighting up with notifications that the eruption had started. We were awake, dressed, and on the road in 15 minutes. By 12:15 a.m. (Thursday morning) we in place at the caldera and clicking madly.

What we saw this evening was not the promised fountaining, but no one was disappointed by the bubbling vent, lava falls, and lava river we did see. The splashes this night reached up to 50 feet, and our vantage point at the Steam Vents gave us a perfect view straight to all the action. We stayed to photograph it until 3:00 a.m., and drove back to the hotel completely euphoric. Needless to say, we passed on the sunrise shoot.

Stay tuned for Part Two…

Unplanned Beauty

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Hawaii, Kilauea, Photography, Sony 100-400 GM, Sony a7R V, volcano Tagged: Big Island, eruption, Hawaii, Kilauea, lava, nature photography, volcano

It’s Not All Skill and Hard Work

Posted on December 7, 2024

There’s not a nature photographer alive who hasn’t heard someone exclaim about a coveted capture, “Wow, you were so lucky!” And indeed we are lucky—but that sentiment completely discounts the time and effort that put us in the right place at the right time.

Louis Pasteur’s assertion that chance favors the prepared mind has been co-opted by photographers—mostly, I suspect, to reclaim some (much deserved) credit for capturing Nature’s ephemeral beauty: vivid sunrises/sunsets, rainbows, lightning, the aurora and other celestial displays, volcanic eruptions, and on, and on….

Yes, it was indeed very lucky when that rainbow appeared, or the sky turned crimson, or the clouds parted to reveal a rising full moon—at just the moment I happened to be there with my camera. Most of those times, despite insinuations to the contrary, my presence wasn’t a total fluke and I’d like credit for it thankyouverymuch.

On the other hand…

Let’s not forget that two things can be equally true. I fear that some photographers become so defensive of the effort they put into capturing a special moment, they fail to appreciate that there was indeed luck involved too. But conceding our good fortune doesn’t diminish our skill and vision, it just acknowledges that we are never in complete control of Nature’s fickle whims. Not only that, appreciating the luck involved helps bolster the sense of wonder and awe a nature photographer must have.

As hard as I try to anticipate an outcome, and the number of times that effort has succeeded, I have to admit that sometimes my presence for a beautiful moment was an absolute fluke. I mean, I still had to know how to work my camera and frame a composition, but what I witnessed was not part of the original plan.

For example, scheduling my 2013 Maui workshop more than a year in advance, I had no inkling of Comet PanSTARRS. When I did learn about the approaching potential naked-eye comet, and that it would be paired with a crescent moon on possibly the best day for viewing, I checked my schedule and discovered that I’d be on Maui for a workshop. In fact, the day the comet would appear closest to the moon just happened to be the day I’d planned to photograph sunset from the summit of Haleakala—coincidentally, the site of the very telescope that discovered PanSTARRS more than a year earlier.

Another special experience I can’t take much credit for was morning I got to photograph the most active, longest lasting Grand Canyon lightning display (that included a rainbow right at sunrise) I’ve ever seen. Based on that morning’s weather forecast (clear skies, 0% chance of rain), and the 12-hour drive home following the shoot, I’d probably have stayed in bed had there not been a workshop group counting on me.

I’m thinking about these unexpected blessings because recently I’ve been going through old, unprocessed images and came across this one (of many) from the September 2023 Kilauea eruption. I’d love to be labeled a Pele-whisperer capable of anticipating a Hawaiian eruption early enough to get myself to the Big Island, blessed with prescient insight into the ideal vantage point before the lava fountains appear. But alas….

I’ve been leading a Hawaii Big Island workshop every year since 2010 (minus the 2020 COVID year). Since Halemaʻumaʻu (Kilauea’s summit caldera) had been erupting continuously since 2008, for the first eight of those years it was easy to take Kilauea for granted. I’d show up, take my group at least one time (often more) to the spot I’d found that perfectly aligned the eruption with the Milky Way. As long as the clouds didn’t deny us, I’d have a workshop full of thrilled photographers.

But in 2018 Pele sent a “don’t ever take me for granted” message, providing a dazzling, 4-month pyrotechnic display before rolling over and going to sleep less than a month before my workshop started. Since 2018, Kilauea has stirred only periodically, so scheduling workshops more than a year in advance has made it impossible to time my workshops to coincide with an eruption.

Putting a positive spin on it, that has made the good fortune of the eruptions we have witnessed even more special. For example, I completely lucked out in 2022 with a nice, albeit distant, eruption that included lava fountains and an opportunity to get the caldera and the Milky Way in the same wide frame.

And then there was 2023. As the workshop approached, things appeared to be back to business as (post-2018) usual. After a couple of minor eruptions over the past year or so, Kilauea had been quiet for several months leading up to my September workshop. Though it had been showing a few signs of stirring, by the day before my workshop, nothing seemed imminent. There’s so much more than enough to photograph on the Big Island, so this wasn’t a big concern, but it was still a minor personal disappointment because I never tire of viewing an erupting volcano.

With the workshop starting Monday, my brother Jay and I had arrived the Friday prior to check out all my workshop locations. We spent Sunday afternoon out of cell phone range, scouting along the Puna Coast, our final area before the workshop. Entering the relatively isolated Puna region, Kilauea was quiet when my phone went dark—so imagine my surprise when we emerged from the cellular void a few hours later to see two notifications from the USGS in my inbox. When I saw Kilauea in the subject line, my heart jumped, but when I opened the first e-mail and saw that it started with, “Kilauea is not erupting,” I scanned the message enough to see that it report signs of increased activity. Okay, then what’s this second message about?

The first sentence grabbed my eyeballs and I didn’t bother to read further: “Kilauea is erupting.” I instantly punched the gas detoured straight to the volcano. The eruption had started at 3:15 p.m., and at exactly 5:00 p.m. we were rolling up to the Visitor Center. There we learned that we could view the eruption right across the street, from Volcano House.

Racing over there, we joined the crowd oooh-ing and ahhh-ing at the billowing smoke, orange glow, and occasional bursts of lava that jumped high enough to be visible the steep crater wall. Rather than photograph from there, I decided to see if there might be a better view. We found more of the same at the steam vents: spurts of lava, lots of smoke, and a distinct orange glow. But while there we ran into a couple who told us the best view was at Keanakakoi, on the other side of caldera. So off we went.

At Keanakakoi we snagged one of the last parking spots, grabbed our camera bags, and bolted down the trail (a paved road now closed to non-official vehicles). After a brisk (understatement) one-mile walk, we made it to the vista about 10 minutes before sunset.

I’ll never forget the sight that greeted us. On the caldera floor clearly visible directly below us were at least a two-dozen lava fountains of varying size, churning among a honeycomb of just-cooled black lava that appeared etched by thin, glowing cracks. Splitting this fiery orgy was a broad lava river, and several narrower streams. We quickly joined the throngs who had jumped the improvised rope that had not doubt been placed to prevent us gawkers from plunging to our deaths (safety-schmafety).

What followed was a clicking frenzy. I started with my 24-105 lens, eventually switching to my 100-400. (I also snuck in a couple of quick iPhone photos—the lava field was close enough to fill the frame without cropping). Monitoring my RGB histogram, I quickly determined that an exposure that completely spared the red channel skewed the rest of the histogram far to the left, which of course made perfect sense and was no problem because pretty much the only thing that mattered in this scene was the orange lava.

So focused was I on scene below me that it was a couple of minutes before I registered that I was working in what might be the windiest conditions I’ve ever photographed in. I’ve probably experienced stronger gusts (I’m looking at you, Iceland), but this wind was steady, brutal, and relentless. So strong in fact that it nearly ripped the glasses of my face, and forced me to actually keep one hand on them most of the time.

Given the rapidly approaching darkness, with most subjects this wind would have been a significant problem. But because my primary (only?) subject was imbued with its own built-in light source, and was in constant, frenetic motion that required an extremely fast shutter speed anyway, I found it all quite manageable—I was actually more concerned about getting blown into the maelstrom than I was about camera shake.

Throughout the evening I varied my exposure settings, shooting wide open with shutter speeds varying between 1/500 and 1/1500 second, and ISOs ranging from 800 to 3200. Focal lengths ranged from fairly wide (wider than 50mm at the start) to 400. In fact, many of my 100-400mm frames were closer to the 100mm range so I could include groups of fountains. I tried to time each shot for peak explosiveness in whatever fountain or fountains I’d targeted, but honestly, since these peaks came every second or two, that wasn’t much of a challenge.

Every once in a while I got a strong whiff of sulfur, a reminder of the risks of being so close to a volcanic eruption. It seemed like we’d been out there at least an hour when I was aware of shouting behind me. I turned to see rangers running around shoeing us from the edge. At first I thought all of us who had crossed the rope barrier were in trouble, but it turns out we were being evacuated—and they meant business. A review of the timestamps on my images showed that what seemed like more than an hour was in fact only 33 minutes.

How close were we to the eruption? I calculated later that we’d been only 1/2 mile away from the lava field, but it seemed much closer. Unfortunately, the closure that caused us to be evacuated wasn’t lifted until the eruption ended, so I wasn’t able to take my group out there. But I did learn about other vantage points that were nearly as good, and got my group out there two more times.

How lucky was I (and my workshop group)? This eruption that started the day before the workshop started, was finished the day after the workshop ended.

Join me in Hawaii

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Lucky Shots

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, Sony 100-400 GM, Sony a7R V, volcano Tagged: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, lava, nature photography, volcano

Fire and Rainbow

Posted on October 10, 2023

One concern about returning to the same location, at the same time, in the same workshop, is finding something new to photograph. But last month’s Hawaii workshop group was so excited about our first shoot of the Kilauea eruption, going back on the workshop’s final night was a no-brainer. Not only were we looking forward viewing the fountaining lava one more time, we all wanted to apply some of the lessons learned from the Tuesday shoot. And Mother Nature delivered a surprise that guaranteed something new for everyone.

Surprise or not, many in the group returned with plans for different exposure or focal length choices; I want to use the knowledge gained in the first visit to position my group better, because the eruption had been so new on that first visit, I’d arrived at Kilauea with no idea of what we’d encounter and how we’d access it. I knew enough this second time to arrive with an actual strategy.

The first night we had to park in the overflow parking lot and walk about a mile along the caldera rim to reach the best vantage points; this time we arrived nearly 90 minutes earlier and drove directly to Kilauea Overlook, our favorite vantage point from the earlier visit. Even arriving that much earlier, we ended up snagging the last three parking spaces in the lot—one more kiss of good fortune to bless this especially fortunate workshop group.

Though the eruption was still going strong, we found the shooting conditions this second evening much different. The first time it was dry, with a mix of sky and clouds; this time we found ourselves surrounded by low clouds that dampened every surface and filled the caldera with a heavy mist. By the end of the evening I’d labeled this a “stealth” rain—microscopic drops that couldn’t really be felt as they landed, but somehow managed to saturate our clothes and accumulate on our lenses. But at first it just seemed a little damp.

As early as we were, the sun still hadn’t set behind Mauna Loa. As we unloaded our gear from the cars, I noticed blue sky visible above Mauna Loa and pointed out to the group that there may actually be enough moisture in the air to create a rainbow if the sun came out. And it wasn’t long after making our way to the rim that the sun did indeed pop out enough to create a fuzzy rainbow far to the left of the lava.

The rainbow’s location was close enough to the eruption that we could include both in the same frame without going too wide, but I wanted to get it even closer to minimize the (not especially appealing) brown caldera floor separating them. This is where understanding basic rainbow science pays off. A rainbow forms a 42 degree circle around the anti-solar point: the point in the sky at the other end of an imaginary, infinitely long line starting at the sun, passing through the back of the viewer’s head, and exiting between the eyes. Since we each have our own anti-solar point (and therefore our own rainbow), which is entirely a function of our position relative to the sun, we can change the location of any rainbow (relative to the landscape) by simply repositioning. In this case I knew I could move about 300 yards to my right before the trail (and eruption view) curved out of view of the eruption and rainbow.

Since this was the workshop’s final evening, and we’d all photographed the eruption from here before, everyone was pretty comfortable scattering (rather than sticking close to me for guidance)—which is exactly what they’d done. I hailed as many as I could and explained what I was doing and why, encouraged them to join me, then rushed up the trail.

Not knowing how long the rainbow would last, on the way I stopped a couple of times to fire a frame or two. Turns out I needn’t have worried because the rainbow lasted, in one form or another, for at least 30 minutes. Once I reached the vantage point that positioned the rainbow closest to the eruption, I set up and went to work. The rainbow seemed most intense near the lava, but at times I could make out a faint full arc, and once even pulled out my 12-24 lens to capture a few frames of it. But for the most park I was interested in the tighter, brighter compositions.

Finally working in one spot long enough to get settled, I started to fully comprehend how wet it was. I was wearing a thin rain shell, but could tell that it was already soaking through to my flannel. (Flannel in Hawaii? Indeed—here at 4,000 feet conditions were both wet and windy, with temps in the low 50s.) The wind made my umbrella pointless, so the mist/rain also assaulted my front lens element enough that I had to wipe it clear every few frames.

The difficult problem was getting focus. I’ve come to trust the autofocus on my Sony mirrorless cameras so much, the only time I manually focus anymore is when I have a critical focus point requirement—in 100% infinity scenes like this, I just autofocus anywhere in the scene (wherever my focus point happens to be positioned) and call it good. But the mist this evening was so dense, I could rarely get a focus confirmation—and even when I did, I wasn’t completely confident of it. So I scanned my surroundings and spied a couple hundred yards behind me one of the volcano observatory buildings (near the now shuttered Jagger Museum) to auto-focus on.

This worked well, especially since I use back-button focus and didn’t need to switch between auto and manual focus each time I refocused. Of course each time I changed my focal length I had to pop my camera off my tripod and turn around to refocus, but this became second nature soon enough.

We stayed until dark, battling the wetness and chill to add to our already brimming Kilauea eruption collections. Once darkness fell, the eruption didn’t look much different than it had the first time, so as soon everyone felt like they’d had enough success and addressed whatever problems they’d identified in their prior images, we retreated to the cars and headed back down to Hilo.

Who wants to find out what we’ll see in Hawaii next year?

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Lots More Rainbows

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, rainbow, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V Tagged: Hawaii, Kilauea, lava, nature photography, Rainbow, volcano

Making Mountains

Posted on May 5, 2018

Night Fire, Halemaumau Crater, Kilauea, Hawaii

Sony a7RII

Tamron 150-600 (Canon-mount with Metabones IV adapter)

1/100 second

F/8

ISO 400

A couple of years ago I was blessed to witness one of our planet’s most spectacular phenomena: an erupting volcano. Kilauea on Hawaii’s Big Island has been in near constant eruption for centuries (millennia?), slowly elevating Hawaii’s slopes and expanding its shoreline with lava that cools and hardens to form the newest rock on Earth. This island building process has been ongoing for the last five-million or so years, as the Pacific Plate slowly slides northwest over a hot spot in Earth’s mantle, building the northwest/southeast-trending Hawaiian chain of islands. The Hawaiian Islands get successively older moving northwest up the chain, with the island of Hawaii currently on the hot-seat, making it the youngest of the chain’s exposed islands (though there is a newer, still submerged island rising south of Hawaii).

As active as Kilauea is, much of its volcanic activity occurs out of the view of the average visitor. But on my annual visit in September of 2016, my workshop group and I got a firsthand look at Kilauea’s island-building furnace when the lava lake inside Halemaumau Crater rose high enough to be seen from the safety of the caldera’s rim. (Read more about this experience in my 2016 blog post, Nature’s Transcendent Moments.)

This week Kilauea is back in the news with an eruption far more significant (and destructive) than the event I captured in this 2016 image. The 2016 experience resulted from the good fortune of catching an elevated phase of the normal summit crater activity that started in 2008. The Kilauea activity that started this week, complete with earthquakes and lava flows, is a new eruption in Kilauea’s east rift zone. It could be over in hours or days, or could continue for decades.

The relatively fluid nature of Hawaiian lava makes its eruptions less “run for your life!” crises and more, “Well, I guess I better start packing up,” events that range from inconvenience to financial disasters, but are rarely life threatening. Local residents know the risk and are generally philosophical and positive when Pele points her fiery finger in their direction.

On the other hand, a volcanic eruption in the Cascade mountains of the Pacific Northwest is potentially far more dangerous than a typical Hawaiian eruption. We only need to look back on the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, a relatively minor event on the continuum of possible Cascade eruptions, to see the extreme power of an explosive eruption. The viscous lava of the Cascade volcanoes makes their eruptions far more dangerous than Hawaii’s eruptions. While Hawaii’s basalt lava flows easily when internal forces push it to the surface, the Cascade lava resists, setting up an irresistible force versus immovable object standoff that is resolved suddenly and explosively (in favor of the irresistible force) as a cataclysmic explosion.

The undeniable aesthetic appeal of the Cascades is actually a byproduct of the the viscous lava that makes them so explosive. As it emerges and flows down the mountain’s side, Cascade lava doesn’t spread too far before cooling in place. The result is a strato-volcano that builds more vertically to form the towering symmetrical cone that photographers love to photograph. The more fluid Hawaiian basalt spreads rather than builds, wreaking slow-motion havoc on the countryside and accumulating over thousands of years to form massive, but visually unimpressive, flat, shield volcanoes.

Having just returned from a couple of weeks photographing in the Pacific Northwest, the beauty of the Cascade volcanoes is fresh in my mind. But nothing compares to witnessing the actual mountain making process in action.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Volcano Gallery

Category: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, Sony a7R II, Tamron 150-600 Tagged: Hawaii, Kilauea, lava, nature photography, volcano

Compromise less, smile more

Posted on November 28, 2017

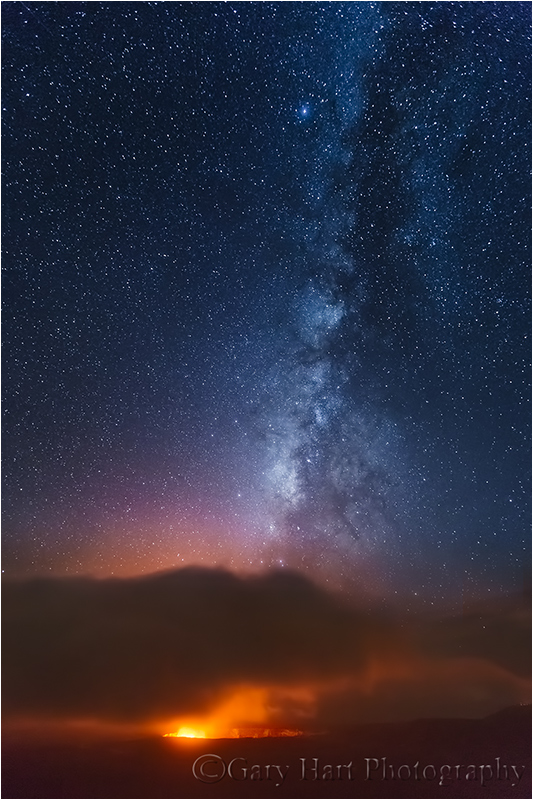

Night Fire, Milky Way Above Kilauea Caldera, Hawaii

Sony a7S II

Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM

10 seconds

F/2.8

ISO 3200

Night photography always requires some level of compromise: extra equipment, ISOs a little too noisy, shutter speeds a little too long, f-stops a little too soft. For years the quality threshold beyond which I wouldn’t cross came far too early and I’d often find myself having to decide between an image that was too dark and noisy, or simply not shooting at all.

Because the almost total darkness of night photography requires a fast lens, the faster the better, one of the first compromises night photography forced on me was adding a night-only lens—a prime lens that was both ultra-fast and wide. Ultra-fast to maximize light capture, wide enough to give me lots of sky and to reduce the star streaking that occurs with the long shutter speeds night photography requires (the wider the focal length, the less visible any motion in the frame).

I started doing night photography as a Canon shooter, so my first night lens was a Canon-mount Zeiss 28mm f/2.0—it did the job but wasn’t quite as fast or wide as I’d have liked. After switching to Sony I added a Sony-mount Rokinon 24mm f/1.4—I loved shooting at f/1.4, and 24mm was a definite improvement over 28mm, but I still found myself wishing for something wider. And the Rokinon had other shortcomings as well: because the camera doesn’t even know the lens is mounted (f-stop set on the lens, not in the camera), I always had to guess the f-stop I used to capture an image. Worse than that, at f/1.4 the Rokinon had pretty significant comatic aberration that made my stars look like little comets.

Since switching to Sony, one compromise I’ve happily made is carrying an extra body that’s dedicated to night photography. Because the Sony a7S and (later) a7SII are just ridiculously good at high ISO, I was able to compensate for the Rokinon’s distortion by stopping down to f/2 or f/2.8 at a higher ISO. The a7SII is worth the extra weight, but I’ve longed for the day when I could replace the Rokinon lens with something wider, and something that had a better relationship with my camera.

That day came earlier this year, when Sony released the 16-35 f/2.8 GM lens. I got to sample this lens before it was released and was surprised by its compactness despite being so wide and fast—it wasn’t long before the 16-35 f/2.8 GM occupied a full-time spot in my camera bag. And in the back of my mind I couldn’t help thinking that the 16-35 GM might just work as a night lens.

I don’t have the time or temperament to be a pixel-peeper, but I had a sense that this lens was pretty sharp wide open, and few things reveal comatic aberration more than stars. I finally got my chance to test the 16-35 GM lens at night on the Hawaii Big Island workshop in September. When this year’s Milky Way images revealed that the 16-35 GM is sharp and pretty much aberration free at f/2.8, I couldn’t have been happier.

As with every night shoot, this night at the caldera I tried a variety of exposure settings to maximize my processing options later. I was pretty pleased to get a clean exposure at 10 seconds (minimal star motion) and f/2.8 (maximum light). While the a7SII doesn’t even breathe hard at the ISO 3200 I used for this image, I know if I were shooting someplace without its own light source (for example, at the Grand Canyon, the bristlecone pine forest, or pretty much any other location lacking an active volcano), I’d probably need to be at ISO 6400 or even 12800 to make a 10 second exposure work. But it’s nice to know that the a7SII and 16-35 f/2.8 GM will do the job even in darkness that extreme.

One more thing

A couple of weeks ago while in Sedona for Sony I got the opportunity to use the new a7RIII. One highlight of that trip was two night shoots with the new camera. I haven’t had a chance to spend any quality time with those images, but I got the sense that its high ISO performance is nearly as good as the a7SII. If that’s true, that will be one less compromise and a lighter camera bag—at least until Sony releases the a7SIII.

Hawaii Photo Workshops

The Milky Way

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, Milky Way, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM, Sony a7S II, stars Tagged: astrophotography, Hawaii, Kilauea, Milky Way, night, stars, volcano

I love you, goodbye…

Posted on November 18, 2015

Last week I said goodbye to my Sony a7S. More than any camera I’ve owned, this is the camera that overcame photography’s physical boundaries that most frustrated me.

I’ve been interested in astronomy since I was ten, ten years longer than I’ve a been photographer. But until recently I’ve been thwarted in my attempts to fully convey the majesty of the night sky above a grand landscape.

What was missing was light. Or more accurately, the camera’s ability to capture light. Light is what enables cameras to “see,” and while there’s still a little light after the sun goes down, cameras struggle mightily to find a usable amount.

When faced with limited light, photographers’ solutions are limited, and each solution is a compromise. In no particular order, we can increase:

- Shutter speed: We can increase the time the light strikes the sensor. While we can usually keep our shutter open for as long as the battery lasts, the longer it’s open, the more motion we capture.

- Aperture (a ratio measure in f-stops): Larger apertures (the f-stop number shrinks as the aperture opens) allow more light, with a loss of depth of field. While the DOF loss is usually insignificant in most night photography scenes (because all subjects are usually at infinity), the laws of optics limit the size of of a lens’s aperture.

- ISO: We can increase the sensor’s sensitivity to light by increasing the ISO, but not without significant image quality degradation (noise).

Most night photography attempts bump into the limits of each solution before complete success is achieved. For me, the first barrier is usually the f-stop, which is soon maxed. With my f-stop maxed, I’m left with a dance between ISO and shutter speed as I attempt to balance acceptable amounts of motion and noise.

So why not just add more light? Duh. But, while adding light solves some problems, it introduces others. Anything bright enough to illuminate a large landscape (sunlight or moonlight) washes out the stars, and artificial local light (such as light painting or a flash) violates my own natural-light-only objective. Another option some resort to is image blending (one frame for the foreground, one for the sky), but that too violates my personal single-frame-only goal.

My first shot at the night photography conundrum came about ten years ago, when I started doing moonlight photography. I immediately found that the reflected sunlight cast by a full moon beautifully illuminated my landscapes, while preserving enough celestial darkness that the brighter, most recognizable constellations still shined through. But walking outside on a clear, moonless night far from city lights was all the reminder I needed that my favorite qualities of the night sky—the Milky Way and the the seemingly infinite quantity of stars—remained beyond my photographic reach.

To photograph a moonless sky brimming with stars, my next step was star trail photography—long exposures that accumulated enough light to reveal my terrestrial subjects at manageable ISO (not too much noise). Star trails have the added benefit of stretching stellar pinpoints into concentric arcs of light that beautifully depict Earth’s rotation.

While both enjoyable and beautiful, moonlight and star trail photography were not completely satisfying. But the laws of physics dictated that lenses weren’t going to get any faster, and Earth wasn’t going to rotate any slower, so the solution would need to be in sensor efficiency.

Unfortunately, camera manufactures remained resolute in their belief that megapixels sold cameras. So as sensor technology evolved, and photographers saw slow but steady high ISO improvement, we were force-fed a mind-boggling increase in megapixel count.

But cramming more megapixels onto a 35mm sensor requires: 1) smaller photosites that are less efficient at capturing light, and 2) more tightly packed photosites that increase (noise inducing) heat.

The megapixel race changed overnight when Sony, in a risky, game-changing move, decided to offer a high-end, full-frame camera with “only” a 12 megapixel sensor. What were they thinking!?

Acknowledging what serious photographers have known for years, that 12 megapixels is enough for most uses (just 12 years ago, pros paid $8,000 for a Canon 1Ds with only 11 megapixels), Sony bucked the megapixel trend to embrace the benefits of fewer, larger, less densely packed photosites. The result was a light-sucking monster that can see in the dark: the Sony a7S.

Since purchasing my a7S less than a year ago, I’m able to photograph the dark night sky above the landscapes I love. Additionally, I found that its fast shutter lag (since matched by the a7R II) made the a7S ideal for lightning photography. It was love at first click.

And now it’s gone. Last month Sony released the a7S II, and given my satisfaction with the upgrade from the a7R to the a7R II, it was only a matter of time before I upgraded to the a7S II. I’m happy to say that I found a good home for my a7S and in fact may even get to visit it in future workshops.

I haven’t had a chance to use the a7S II, but I assure you it won’t be long, and you’ll be the first to know.

About this image

The image at the top of this post was captured in September (2015) during my Hawaii Big Island Volcanos and Waterfalls photo workshop. Each time I visit here I hold my breath until I see what the sky is doing. I’ve encountered everything from completely cloudless to pea soup fog. I’ve come to hope for a mix of clouds and sky—enough sky for the Milky Way to shine through clearly, but enough clouds to reflect the orange light of the churning volcano.

On this evening we got a combination I hadn’t seen before—clear sky overhead, a few low clouds, and a heavy mist hanging in the caldera. Not only did the mist frame the scene with a translucent orange glow, it subdued the volcano’s fire enough for me to use a long exposure to bring out the Milky Way without blowing my highlights.

We’ll do it again in my next Hawaii Volcanos and Waterfalls workshop

An a7S homage

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, Milky Way, Sony a7S, stars, volcano Tagged: Big Island, Hawaii, Kilauea, Milky Way, nature photography, night photography, Photography, volcano

A small dose of mind-bending perspective

Posted on October 12, 2014

So what’s happening here? The orange glow at the bottom of this frame is light from 1,800° F lava bubbling in Halemaʻumaʻu Crater inside Hawaii’s Kilauea Caldera, reflecting off a low-hanging bank of clouds. The white band above the crater is light cast by billions of stars at the center our Milky Way galaxy. So dense and distant are the stars here, their individual points are lost to the surrounding glow. Partially obscuring the Milky Way’s glow are large swaths of interstellar dust, the leftovers of stellar explosions and the stuff of future stars. Completing the scene are stars in our own neighborhood of the Milky Way, stars close enough that we see them as discrete points of light that we imagine into mythical shapes—the constellations.

The Milky Way galaxy is home to every single star we see when we look up at night, and 300 billion more we can’t see—that’s nearly 50 stars for every man, woman, and child on Earth. Our Sun, the central cog in the solar system that includes Earth and the other planets wandering our night sky, is a minor player in a spiral arm near the outskirts of the Milky Way. But before you get too impressed with the size of the Milky Way, consider that it’s just one of 500 billion or so galaxies in the known Universe—that’s right, there are more galaxies in the Universe than stars in our galaxy.

Everything we see is the product of light—light created by the object itself (like the stars), or created elsewhere and reflected (like the planets). Light travels incredibly fast, fast enough that it can span even the two most distant points on Earth faster than humans can perceive, fast enough that we consider it instantaneous. But distances in space are so great that we don’t measure them in terrestrial units of distance like miles or kilometers. Instead, we measure interstellar distance by the time it takes for a beam of light to travel between two objects—one light-year is the distance light travels in one year.

The ramifications of cosmic distance are mind-bending. Imagine an Earth-like planet revolving the star closest to our solar system, about four light-years away. If we had a telescope with enough resolving power to see all the way down to the planet’s surface, we’d be watching that planet’s activity from four years ago. Likewise, if someone on that planet today (in 2014) were watching us, they’d see Lindsey Vonn claiming the gold in the Women’s Downhill at the Vancouver Winter Olympics, and maybe learn about the unfolding WikiLeaks scandal.

In this image, the caldera’s proximity makes it about as “right now” as anything in our Universe can be—the caldera and I are sharing the same instant in time. On the other hand, the light from the stars above the caldera is tens, hundreds, or thousands of years old—it’s new to me, but to the stars it’s old history. Not only that, every point of starlight here is a version of that star created in a different instant in time. It’s possible for the actual distance separating two stars to be so great, that we see light from the younger star that’s older than the light from the older star.

So what’s the point of all this mind bending? Perspective. It’s easy (essential?) for humans to overlook our place in this larger Universe as we negotiate the family, friends, work, play, eat, and sleep that defines our very own personal universes. I doubt we could cope otherwise. But when I start taking my life too seriously, it helps to appreciate my place in the larger Universe. Nothing does that better for me than quality time with the night sky.

About this image

My 2014 Hawaii Big Island photo workshop group made three trips to photograph the Kilauea Caldera beneath the Milky Way. On the first night we got a lot of clouds, with a handful of stars above, and just a little bit of Milky Way. Nice, but not the full Milky Way everyone hoped for. So I brought everyone back a couple nights later—this time we got about ten minutes of quality Milky Way photography before the clouds closed in. The following night we gave the caldera one more shot and were completely shut out by clouds. Such is the nature of night photography in general, and on Hawaii in particular. This image is from our second visit.

My concern that night was making sure everyone was successful, ASAP. I started with a test exposure to determine the exposure settings that would work best for that night (not only does each night’s ambient light vary with the volcanic haze, cloud cover, and airborne moisture, the caldera’s brightness varies daily too). Once I got the exposure down and called it out to the group, most of my time was spent helping people find and check their focus, and refine their compositions (“More sky! More sky!”). Bouncing around in the dark, I’d occasionally stop at my camera long enough to fire a frame, never staying long enough to see the image pop up on the LCD. I ended up with a half dozen or so frames, including this one from early in the shoot.

Join me on the Big Island next year

Learn more about starlight photography

A starlight gallery

Click an image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide show

One eye on the ocean, the other on the volcano

Posted on September 16, 2014

September 16, 2014

It’s easy to envy residents of Hawaii’s Big Island—they enjoy some of the cleanest air and darkest skies on Earth, their soothing ocean breezes ensure that the always warm daytime highs remain quite comfortable, and the bathtub-warm Pacific keeps overnight lows from straying far from the 70-degree mark. Scenery here is a postcard-perfect mix of symmetrical volcanoes, lush rain forests, swaying palms, and lapping surf. I mean, with all this perfection, what could possibly go wrong?

Well, let me tell you….

Last month Tropical Storm Iselle, just a few hours removed from hurricane status, slammed Hawaii’s Puna Coast with tree-snapping winds and frog-drowning rain that cut electricity, flooded roads, and disrupted many lives for weeks. Touring the area in and around Hilo, it’s easy to appreciate Hawaiian resilience—thanks to quick action, hard work, and continuous smiles, most visitors would find it difficult to believe what happened here just a month ago. But on the drive south of Hilo along the Puna Coast, I witnessed firsthand Iselle’s power in its aftermath. There beaches have been rearranged beyond recognition and entire forests have been leveled.

But despite its impact, Iselle is already old news. This month residents of Hawaii’s Puna region have done a 180, turning their always vigilant eyes away from the ocean and toward the volcano. In late June Kilauea’s Pu`u `O`o Crater dispatched a river of lava down the volcano’s southeast flank. Since Pu`u `O`o has been erupting continuously since 1983, this latest incursion didn’t initially raise many eyebrows. But the flow has persisted, advancing now at about 250 yards per day. While this isn’t “Run-for-your life!” speed, it’s more like high stakes water torture because there’s very little that can be done to stop, slow, or even deflect the lava’s inexorable march. Residents of the communities of Kaohe and Pahoa can do nothing but watch, pray, and prepare—if the volcano persists, they’re wiped out. Not only that, the lava flow also threatens the Pahoa Highway, currently the only route in and out for the thousands of residents of the Puna region.

Recent reports of increased activity on Muana Loa have also notched up the anxiety. Lava from its last eruption, in 1984, threatened Hawaii’s capital, Hilo, before petering out with just a few miles to spare. Because Muana Loa eruptions tend to be larger and more explosive than Kilauea eruptions, any increased activity there is taken very seriously.

Had enough? Well, there’s more thing: With its funnel-shaped bay and bullseye placement in the Pacific Ring of Fire, Hilo is generally considered the most tsunami vulnerable city in the world. Fatal tsunamis have struck the Big Island in 1837, 1868, 1877, 1923, 1946, 1960, and 1975. Yesterday my photo workshop group photographed sunrise at Laupahoehoe Point, where damage from the most deadly tsunami to strike American soil is still visible. That tsunami, in 1946 (before Hawaii became a state), traveled 2,500 miles from the Aleutian Islands to kill 159 Hawaiians, including 20 schoolchildren and 4 teachers in Laupahoehoe.

Despite this shopping list of threats and hardship, I don’t get the sense the Hawaiians want sympathy. Despite the unknown but potentially devastating consequences facing them, both imminent and potential, no one here is feeling sorry for themselves. There’s much talk about the current lava flow that will directly or indirectly impact every resident of the Big Island’s Hilo side, but no hand-wringing—life goes on and smiles abound. Indeed, everyone here seems to have sprung into action in one way or another, shoring up old long abandoned roads (the jungle claims anything left unattended with frightening speed), helping people move possessions to safe ground, offering temporary shelter, and whatever else might help.

The Aloha spirit is alive and well, and I have no doubt that it will persevere in the face of whatever adversity Nature throws at them.

About this image

My Hawaii photo workshop began Monday afternoon, but my brother and I arrived on the Big Island on Friday because I hate doing any workshop without first running all my locations to make sure there are no surprises. And this time it turned out to be a wise move—not only did I get a couple of extra days in paradise, I did indeed encounter surprises, courtesy of Iselle, when I discovered two of my go-to locations rendered inaccessible by storm damage. I spent Saturday searching for alternatives and by Saturday’s end had a couple of great substitute spots. That night we celebrated with a night shoot on Kilauea. (I was going to visit Kilauea anyway, but if I’d still been stressing about my locations, I probably wouldn’t have been in the right mindset to photograph.)

We arrived to find the Milky Way glowing brightly above the caldera and immediately started shooting. Because I don’t have as many horizontal compositions of the caldera as vertical, I started horizontal. By the time I’d captured a half dozen or so frames, a heavy mist dropped into the caldera to quickly obscure the entire view (one more example of our utter helplessness to the whims of Nature).

In this frame I went quite wide, not only to capture as much of the Milky Way as possible, but also to include all of the thin cloud layer painted orange by the light of the caldera’s fire. This is a single click (no blending of multiple images), though I did clone just a little bit of color back into the hopelessly blown center of the volcano’s flame.

A Kilauea Gallery

Click and image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide slow

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About