Gifts From Heaven

Posted on November 3, 2024

Heaven Sent, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS Above the Sierra Crest, Alabama Hills

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 3200

f/4

5 seconds

As much for its (apparently) random arrival as its ethereal beauty, the appearance of a comet has always felt to me like a gift from the heaven. Once a harbinger of great portent, scientific knowledge has eased those comet fears, allowing Earthlings to simply appreciate the breathtaking display.

Unfortunately, scientific knowledge does not equal perfect knowledge. So, while a great comet gives us weeks, months, or even years advance notice of its approach, we can never be certain of how the show will manifest until the comet actually arrives. For every Comet Hale-Bopp, that gave us nearly two years warning before becoming one of the most widely viewed comets in human history, we get many Comet ISONs, which ignited a media frenzy more than a year before its arrival, then completely fizzled just as the promised showtime arrived. ISON’s demise, as well as many highly anticipated comets before and after, taught me not to temper my comet hopes until I actually put eyes on the next proclaimed “comet of the century.” Nevertheless, great show or not, the things we do know about comets—their composition, journey, arrival, and (sometimes) demise—provide a fascinating backstory.

In the simplest possible terms, a comet is a ball of ice and dust that’s (more or less) a few miles across. After languishing for eons in the coldest, darkest reaches of the Solar System, perhaps since the Solar System’s formation, a gravitational nudge from a passing star sends the comet hurtling sunward, following an eccentric elliptical orbit—imagine a stretched rubber band. Looking down on the entire orbit, you’d see the sun tucked just inside one extreme end of the ellipse.

The farther a comet is from the sun, the slower it moves. Some comets take thousands, or even millions, of years to complete a single orbit, but as it approaches the sun, the comet’s frozen nucleus begins to melt. Initially, this just-released material expands only enough to create a mini-atmosphere that remains gravitationally bound to the nucleus, called a coma. At this point the tail-less comet looks like a fuzzy ball when viewed from Earth.

This fuzzy phase is usually the state a comet is in when it’s discovered. Comets are named after their discoverers—once upon a time this was always an astronomer, or astronomers (if discovered at the same time by different astronomers), but in recent years, most new comets are discovered by automated telescopes, or arrays of telescopes, that monitor the sky, like ISON, NEOWISE, PANSTARRS, and ATLAS. Because many comets can have the same common name, astronomers use a more specific code assembled from the year and order of discovery.

As the comet continues toward the sun, the heat increases further and more melting occurs, until some of the material set free is swept back by the rapidly moving charged particles of the solar wind, forming a tail. Pushed by the solar wind, not the comet’s forward motion, the tail always fans out on the side opposite the sun—behind the nucleus as the comet approaches the sun, in front of the comet as it recedes.

Despite accelerating throughout its entire inbound journey, a comet will never move so fast that we’re able to perceive its motion at any given moment. Rather, just like planets and our moon, a comet’s motion relative to the background stars will only be noticeable when viewed from one night to another. And like virtually every other object orbiting the sun, a comet doesn’t create its own light. Rather, the glow we see from the coma and tail is reflected sunlight. The brilliance of its display is determined by the volume and composition of the material freed and swept back by the sun, as well as the comet’s proximity to Earth. The color reflected by a comet’s tail varies somewhat depending on its molecular makeup, but usually appears as some shade of yellow-white.

In addition to the dust tail, some comets exhibit an ion tail that forms when molecules shed by the comet’s nucleus are stripped of electrons by the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Being lighter than dust molecules, these ions are whisked straight back by the solar wind. Instead of fanning out like the dust tail, these gas ions form a narrow tail that points directly away from the sun. Also unlike the dust tail that shines by reflected light, the ion tail shines by fluorescence, taking on a blue color courtesy of the predominant CO (carbon monoxide) ion.

One significant unknown upon discovery of a new comet is whether it will survive its encounter with the sun at all. While comets that pass close to the sun are more likely to shed large volumes of ice and dust, many sun-grazing comets approach so close that they’re overwhelmed by the sun’s heat and completely disintegrate.

With millions of comets in our Solar System, it would be easy to wonder why they’re not a regular part of our night sky. Actually, Earth is visited by many comets each year, though most are so small, and/or have made so many trips around the sun that they no longer have enough material to put on much of a show. And many comets never get close enough to the sun to be profoundly affected by its heat, or close enough to Earth to shine brightly here.

Despite all the things that can go wrong, every once in a while, all the stars align (so to speak), and the heavens assuage the disappointment of prior underachievers with a brilliant comet. Early one morning in 1970, my dad woke me and we went out in our yard to see Comet Bennett. This was my first comet, a sight I’ll never forget. I was disappointed by the faint smudges of Comet Kohoutek in 1973 (a complete flop compared to its advance billing), and Halley’s Comet in 1986 (just bad orbital luck for Earthlings). Comet Hale-Bopp in 1996 and 1997 was wonderful, while Comet ISON in 2012 disintegrated before it could deliver on its hype.

In 2013 Comet PANSTARRS didn’t put on much of a naked-eye display, but on its day of perihelion, I had the extreme good fortune to be atop Haleakala on Maui, virtually in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. Even though I couldn’t see the it, using a thin crescent moon I knew to be just 3 degrees from the comet to guide me, I was able to photograph PANSTARRS and the moon together. Then, in the dismal pandemic summer of 2020, Comet NEOWISE surprised us all to put on a beautiful show. I made two trips to Yosemite to photograph it, then was able to photograph it one last time at the Grand Canyon shortly before it faded from sight.

October 2024 promised the potential for two spectacular comets, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS (C/2023 A3) in the first half of the month, and Comet ATLAS (C/2024 S1) at the end of the month. Alas, though this second comet had the potential to be much brighter, it pulled an Icarus and flew too close to the sun (RIP). But Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was another story, brightening beyond expectations.

I shared the story of my trip to photograph Tsuchinshan–ATLAS in my October 16 I’m Not Crazy, I Swear… blog post, but have a couple of things to add about this image. First is how important it is to not get so locked into one great composition that you neglect capturing variety. I captured this wider composition before the image I shared a couple of weeks ago, and was pretty thrilled with it—thrilled enough to consider the night a great success. But I’m so glad that I changed lenses and got the tighter vertical composition shortly before the comet’s head dropped out of sight.

And second is the clearly visible anti-tail that was lost in thin haze near the peaks in my other image. An anti-tail is a faint, post-perihelion spike pointing toward the sun in some comets, caused when larger particles from the coma, too big to be pushed by the solar wind, are left behind. It’s only visible from Earth when we pass through the comet’s orbital plane. Pretty cool.

When will the next great comet arrive? No one knows, but whenever that is, I hope I’ve kindled enough interest that you make an effort to view it. But if you plan to chase comets, either to photograph or simply view, don’t forget the wisdom of astronomer and comet expert, David Levy: “Comets are like cats: they have tails, and do precisely what they want.”

Join me in my Eastern Sierra photo workshop

More Gifts From Heaven

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Full Contact Photography

Posted on October 24, 2024

Years ago, my brother Jay and I were photographing an autumn sunrise at Mono Lake’s South Tufa. Among the first to arrive at the lake, we’d set up at the spot I’d chosen the prior evening, but soon South Tufa’s shoreline was jammed with jostling, elbow-to-elbow photographers. Scanning the line of overlapping tripod legs, I was baffled because, unlike many popular photo destinations, South Tufa has many beautiful places to set up, offering ample opportunity to create something unique. But the sole deciding criterion for these photographers seemed to be, Well, someone else is set up here, so this must be the spot. And they kept coming. It got so bad that at one point we witnessed two photographers who, rather than set out in search of something to make their own, almost come to blows over a 3-foot square of choice lakeside real estate. That was when I told myself there must be other locations at this special lake that aren’t saturated with photographers content to settle for barely distinguishable versions of the same scene.

Sunrise Mirror, Mono Lake

That afternoon Jay and I explored the network of rutted, unpaved roads encircling Mono Lake, ending up completely alone for sunset, across the lake at a remote beach dotted with low tufa platforms jutting from mirror reflections. Undeterred by the maze-like drive, and a half-mile or so walk to the lake that started in thick volcanic sand and ended in shoe-sucking mud, we were so pleased with our sunset experience that we vowed to return for sunrise the next morning.

But the story didn’t end there because, despite meticulously logging (in that pre-smart phone and GPS time) each odometer click between turns on the way back, the following morning we still got hopelessly lost trying to reverse-execute the prior night’s exit in the dark. With the eastern horizon starting to brighten, I stopped by the first wide spot that was relatively close to the lake, and we hoofed it cross-country through more sand and mud to beat the sunrise.

The show that morning was one of the most memorable sunrises of my life. The juxtaposition of those two mornings reinforced for me the joy of experiencing Nature in relative peace. And though I didn’t realize it at the time, that realization influences an approach to my subjects that continues to this day: rather than settle for the views most trampled, no matter how spectacular, I started challenging myself to seek less obvious places to plant my tripod.

Honestly, I enjoy sharing Nature’s beauty with kindred spirits almost (even just) as much as I do photographing in complete solitude. But sadly, the hostile display Jay and I witnessed that morning at South Tufa, fueled by the digital renaissance, was only the first in what feels like a growing epidemic of full-contact photography: the inevitable consequence of too many photographers trying to force themselves into spaces too small, simply so they can replicate images already captured many times.

For example, a collapsed riverbank caused the NPS to permanently close Southside Drive to Horsetail Fall aspirants, and the Navajo have justifiably banned tripods in Antelope Canyon. And I’m surprised that (as far as I know) no one has fallen, or been shoved, over the cliff in the Mesa Arch sunrise scrum.

Whether the agitation escalates to fisticuffs, or the governing entity closes the location or imposes Draconian restrictions, no one wins. And the “contact” doesn’t need to be physical—often mere proximity can escalate tension enough to ruin things for everyone.

Here are a few examples of bad photographer behavior, brought on by some photographers’ inability to play well with others, that I’ve witnessed myself:

- During one Grand Canyon sunset, a very well known photographer with a “Do you know who I am?” attitude set up with the railed vista between himself and the scene he wanted to photograph, then started ranting at a pair of European tourists (not even photographers) for walking into “his” scene. They were clearly taken aback—when I saw them timidly start to leave, I rushed over and apologized on behalf of all photographers and Americans, telling them they’d done nothing wrong and have every right to stand there and enjoy the view for as long as they’d like.

- In Iceland last February, a couple of photographers (who should know better!) walked out in front of the bridge where my and Don Smith’s workshop group had set up to photograph a waterfall. Not only did they turn deaf ears to our requests for them exit our scene, they trampled the formerly pristine snow that had made the scene so special. Adding insult to injury, one of them sent up a drone, completely ignoring the many signs forbidding them.

- One morning at North Lake (Eastern Sierra), some guy had his tripod set up far behind, and in direct line with, the section of lakeshore where dozens of photographers had set up. Then he proceeded to aggressively shoo everyone away, essentially claiming the entire North Lake scene for himself. I tried reasoning with him, but when he seemed unwilling to compromise, we all just ignored him. When he came rushing down, looking to punch someone, a photographer who was much larger than him (and pretty much everyone else there) calmly sauntered up and asked him what the problem was—at which point he suddenly remembered someplace else he had to be.

- And probably my personal “favorite” is the guy who, at everyone’s favorite Schwabacher Landing Grand Tetons reflection view, donned waders and walked out into the water in front 50 or so other photographers waiting for sunrise. Despite gentle requests, pleading, and eventually enraged threats, he refused to budge. I think the only thing that spared his life was the fact that low clouds obscured the peaks and sunrise light that morning.

All of these experiences have informed my approach to all my locations, whether I’m on my own or leading a group. Of course as a photo workshop leader, I need to balance that instinct with the understanding that for many of my students, my workshop might be the only time they’ve visited this location, and may very much want their own versions of the most popular scenes. So in a workshop, I always make sure to blend a combination of familiar spots with my own “secret” (few locations in nature photography are truly secret) spots.

But anyway…

Over the last two decades I’ve returned to this relatively untouched side of Mono Lake, both by myself and leading groups. With no trail from the road to the lake, each time I wind up at a slightly different spot, but so far have never been disappointed.

The October morning I captured this image was wonderfully calm, with the reflections only slightly disturbed by gentle undulations. I had to move around a bit to organize the relationships between the foreground tufa mounds, but quickly landed at this spot. With mostly clear skies, I limited the sky in my composition, emphasizing the graduated colors reflecting atop the lake instead.

I wanted to smooth the rolling swells into a flat, gauzy reflection, while underexposing enough to avoid washing out the sky’s pre-sunrise natural color. Still nearly 30 minutes before the sun arrived, the scene was still dark enough to allow a 30-second exposure without an ND filter. With a fairly wide lens and not a lot of close foreground detail, depth of field was pretty easy—it probably didn’t matter, but I focused on the right-most tufa mound.

I photographed until the sun appeared, but took enough time between frames to appreciate the utter solitude of my surroundings, and contrasted them with the mayhem I knew was happening across the lake. The irony of the full contact experience over there driving me to find the isolation here, wasn’t lost on me.

Photograph Mono Lake with me in my Eastern Sierra workshop

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

More Mono Magic

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

I’m Not Crazy, I Swear…

Posted on October 16, 2024

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and Mt. Whitney, Alabama Hills, California

Sony α1

Sony 100-400 GM

5 seconds

f/5.6

ISO 3200

Crazy is as crazy does

In college, my best friend and I drove from San Francisco to San Diego so he could attend a dental appointment he’d scheduled before his recent move back to the Bay Area. We drove all night, 10 hours, arriving at 7:55 a.m. for his 8:00 a.m. appointment (more luck than impeccable timing). I dozed in the car while he went in; he was out in less than an hour, and we drove straight home. I remember very little of the trip, except that each of us got a speeding ticket for our troubles. Every time I’ve told that story, I’ve dismissed it with a chuckle as the foolishness of youth. Now I’m not so sure that youth had much to do with it at all.

I’m having second thoughts on the whole foolishness of youth thing because on Monday, my (non-photographer) wife and I drove nearly 8 hours to Lone Pine so I could photograph Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS setting behind Mt. Whitney. We arrived at my chosen location in the Alabama Hills about 15 minutes after the 6:20 sunset, then waited impatiently for the sky to darken enough for the comet to appear. I started photographing at around 7:00, and was done when the comet’s head dropped below Mt. Whitney at 7:30. After spending the night in Lone Pine, we left for home first thing the next morning, pulling into the garage just as the sun set. For those who don’t want to do the math, that’s 16 hours on the road for 30 minutes of photography.

In my defense, for this trip I had the good sense (and financial wherewithal) to get a room in Lone Pine Monday night, and didn’t get pulled over once. That this might have been a crazy idea never occurred to me until I was back at the hotel, and that was only in the context of how the story might sound to others—in my mind this trip was worth every mile, and I have the pictures to prove it.

I say that fully aware that my comet pictures will no doubt be lost in the flood of other Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS images we’ll see over the next few weeks, many no doubt far more spectacular than mine. My excitement with the fruits of this trip is entirely personal, and to say I’m thrilled to have witnessed and photographed another comet would be an understatement—especially in light of last month’s Image of the Month e-mail citing comets as one of the three most beautiful celestial subjects I’ve ever witnessed. And of those three, comets feel the most personal to me.

Let me explain

When I was ten, my best friend Rob and I spent most of our daylight hours preparing for our spy careers—crafting and trading coded messages, surreptitiously monitoring classmates, and identifying “secret passages” that would allow us to navigate our neighborhood without being observed. But after dark our attention turned skyward. That’s when we’d set up my telescope (a castoff generously gifted by an astronomer friend from my dad’s Kiwanis Club) on Rob’s front lawn (his house had a better view of the sky than mine) to scan the heavens hoping that we might discover something: a comet, quasar, supernova, black hole, UFO—it didn’t really matter. And repeated failures didn’t deter us.

Nevertheless, our celestial discoveries, while not Earth-changing, were personally significant. Through that telescope we saw Jupiter’s moons, Saturn’s rings, and the changing phases of Venus. We also learned to appreciate the vastness of the universe with the observation that, despite their immense size, stars never appeared larger than a pinpoint, no matter how much magnification we threw at them.

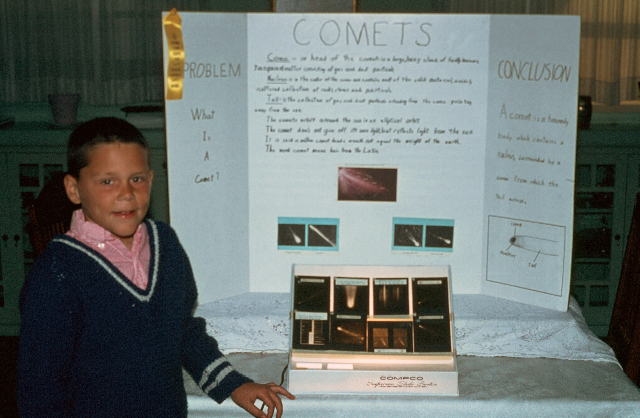

To better understand what we saw, Rob and I turned to illustrated astronomy books. Pictures of planets, galaxies, and nebula amazed us, but we were particularly drawn to the comets: Arend-Roland, Ikeya–Seki, and of course the patriarch of comets, Halley’s Comet (which we learned was scheduled to return in 1986, an impossible wait that might as well have been infinity). With their glowing comas and sweeping tails, it was difficult to imagine that anything that beautiful could be real. When it came time to choose a subject for the annual California Science Fair, comets were an easy choice. And while we didn’t set the world on fire with our project presentation, Rob and I were awarded a ribbon of some color (it wasn’t blue), good enough to land us a spot in the San Joaquin County Fair. (Edit: Uncovering the picture, I see now that our ribbon was yellow.)

Here I am with the fifth grade science project that started it all. (This is only half of the creative team—somewhere there’s a picture that includes Rob.)

The next milestone in my comet obsession occurred a few years later, after my family had moved to Berkeley and baseball had taken over my life. One chilly winter morning my dad woke me and urged me outside to view what I now know was Comet Bennett. Mesmerized, my smoldering comet interest flamed instantly, expanding to include all things astronomy. It stayed with me through high school (when I wasn’t playing baseball), to the point that I actually entered college with an astronomy major that I stuck with for several semesters, until the (unavoidable) quantification of the concepts I loved sapped the joy from me.

While I went on to pursue other things, my affinity for astronomy continued, and comets in particular remained special. Of course with affection comes disappointment: In 1973 Kohoutek fizzled spectacularly, a failure that somewhat prepared me for Halley’s anticlimax in 1986.

By the time Halley’s arrived, word had come down that it was poorly positioned for its typical display (“the worst viewing conditions in 2,000 years”), making it barely visible this time around, but I can’t wait until 2061! (No really—I can’t wait that long. Literally.) Nevertheless, venturing far from the city lights one moonless January night, I found great pleasure locating without aid (after much effort), Halley’s faint smudge in Aquarius.

After many years with no naked-eye comets of note, 1996 arrived with the promise of two great comets. While cautiously optimistic, Kohoutek’s scars prevented me from getting sucked in by the media frenzy. So imagine my excitement when, in early 1996, Comet Hyakutake briefly approached the brightness of Saturn, with a tail stretching more than twenty degrees (forty times the apparent width of a full moon).

But as beautiful as it was, Hyakutake proved to be a mere warm-up for Comet Hale-Bopp, which became visible to the naked eye in mid-1996 and remained visible until December 1997—an unprecedented eighteen months. By spring of 1997 Hale-Bopp had become brighter than Sirius (the brightest star in the sky), its tail approaching 50 degrees. I was in comet heaven. But alas, family and career had preempted my photography pursuits and I didn’t photograph Hale-Bopp.

Comet opportunities again quieted after Hale-Bopp. Then, in early 2007, Comet McNaught caught everyone off-guard, intensifying unexpectedly to briefly outshine Sirius, trailing a thirty-five degree, fan-shaped tail. McNaught put on a much better show in the Southern Hemisphere; in the Northern Hemisphere, because of its proximity in the sky to the sun, it provided a very small window of visibility, and was easily lost in the bright twilight. This, along with its sudden brightening, prevented McNaught from becoming the media event Hale-Bopp was. I only found out about it by accident, on the last day it would be easily visible in the Northern Hemisphere. By then digital capture had rekindled my photography interest (understatement), so despite virtually no time to prepare, I grabbed my camera and headed to the foothills east of Sacramento, where I managed to capture the McNaught image I share in the gallery below—my first successful comet capture.

Following McNaught, I vowed not to be caught off guard by a comet again. After enduring the frustration of promising (over-hyped?) comets disintegrated by the sun (you broke my heart, Comet ISON), and seeing others’ images of spectacular Southern Hemisphere-only comets (I’m looking at you, Comet Lovejoy), my heart jumped when I came across a website proclaiming the approach of Comet PANSTARRS (a.k.a, C/2011 L4 in less glamorous astro-nerd parlance), discovered not by an individual, but by the Pan-STARRS automated telescope array atop Haleakala on Maui.

Researching further, I learned that PANSTARRS could (fingers crossed) hang low in the western sky at magnitudes brighter than Saturn, for about a week right around its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) in March 2013, remaining visible as it rises but dims over the following few weeks. Checking my calendar to see if I had any conflicts that week, I realized I’d be on Maui for my workshop during PANSTARRS’ perihelion! Turns out my first viewing of PANSTARRS was atop Haleakala, almost literally in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. I also got to photograph a rapidly fading PANSTARRS above Grand Canyon on its way back to the farthest reaches of the Solar System.

Then, in 2020, came Comet NEOWISE to brighten our pandemic summer. I was able to make two trips to Yosemite and another to Grand Canyon to photograph NEOWISE (the Yosemite trips were for NEOWISE only).

One more time

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS has been on my radar for at least a year, but not something I monitored closely until September, when it became clear that it was brightening as, or better than, expected. By the end of September I knew that the best Northern Hemisphere views of Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would be in mid-October, but since I was already in the Alabama Hills at the end of September, just a couple of days after the comet’s perihelion, I went out to look for it in the pre-sunrise eastern sky (opposite the gorgeous Sierra view to the west). No luck, but that morning only solidified my resolve to give it another shot when it brightened and returned to the post-sunset sky.

At that point I had no detailed plan, and hadn’t even plotted its location in the sky beyond knowing it would be a little above the western horizon shortly after sunset in mid-October. My criteria were a nice west-facing view, distant enough to permit me to use a moderate telephoto lens. After ruling out the California coast (no good telephoto subjects) and Yosemite Valley (no good west-facing views), I soon realized I’d be returning to the east side of the High Sierra.

At that point I started working on more precise coordinates and immediately eliminated my first (and closest) candidate, Olmsted Point, because the setting comet didn’t align with Half Dome. My next choice was Minaret Vista (near Mammoth), a spectacular view of the jagged Minaret range and nearby Mt. Ritter and Mt. Banner. This was a little more promising—the alignment wasn’t perfect, but it was workable. Then I looked at the Alabama Hills and Mt. Whitney and knew instantly I’d be reprising the long drive back down 395 to Lone Pine.

Though its intrinsic magnitude faded each day after its September 27 perihelion, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS’s apparent magnitude (visible brightness viewed from Earth) continued to increase until its closest approach to Earth on October 12. While its magnitude would never be greater than it was on October 12, the comet was still too close to the sun to stand out against sunset’s vestigial glow. But each night it climbed in the sky, a few degrees farther from the sun, toward darker sky.

Though Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would continue rising into increasingly dark skies through the rest of October, and each night would offer a longer viewing window than the prior night, I chose October 14 as the best combination of overall brightness and dark sky. An added bonus for my aspirations to photograph the comet with Mt. Whitney and the Sierra Crest would be the 90% waxing gibbous moon rising behind me, already high enough by sunset to nicely illuminate the peaks after dark, but still far enough away not to significantly wash out the sky surrounding the comet.

At my chosen spot, I set up two tripods and cameras, one armed with my Sony a7RV and 24-105 lens, the other with my Sony a1 and 100-400 lens. I selected that first location because it put the comet almost directly above Mt. Whitney, 16 degrees above the horizon, at 7 p.m. But since the Sierra crest rises about 10 degrees above the horizon when viewed from the Alabama Hills, I knew going in that the comet’s head would slip behind the mountains at 7:30, slamming shut my window of opportunity after only 30 minutes.

When it first appeared, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was high enough that I mostly used my 24-105 lens. But as it dropped and moved slightly north (to the right), away from Whitney, we hopped in the car and raced about a mile south, to the location I’d chosen knowing that Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would align perfectly with Whitney as it dropped below the peaks. Most of my images from this location were captured with my 100-400 lens.

I manually focused on the comet’s head, or on a nearby relatively bright star, then checked my focus after each image. The scene continued darkening as I shot, and to avoid too much star motion I increased my ISO rather than extending my shutter speed.

As I photographed, I could barely contain my excitement at the image previews on my cameras’ LCD screens. Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and its long tail were clearly visible to my eyes, but the cameras’ ability to accumulate light made it much brighter than what we saw. The image I share today is one of my final images of the night. Even with a shutter speed of only 5 seconds, at a focal length of right around 200mm, if you look closely you’ll still see a little star motion.

My giddiness persisted on the drive back to Lone Pine and into our very nice (and hard earned) dinner. When our server expressed interest in the comet, I went out to the car and grabbed my camera to share my images with her. Whether or not the enthusiasm she showed was genuine, she received a generous tip for indulging me. And even though I usually wait until I’m home to process my images on my large monitor, I couldn’t help staying up well past lights-out to process this one image, just to reassure myself that I hadn’t messed something up (focus is always my biggest concern during a night shoot).

And finally…

FYI, neither Rob nor I became spies, but we have stayed in touch over the years. In fact, the original plan was for him to join me on this adventure, but circumstances interfered and he had to stay home. But we still have hopes for the next comet, which could be years away, or as soon as late this month….

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

My Comet History

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

No Sky? No Problem…

Posted on October 10, 2024

Anyone who has been in one of my photo workshops will confirm that I’m kind of obsessed with skies. Not just the good skies, but the bad ones too. While the sky can add a lot to an image, it can detract just as much. Viewing images online and in my workshop image reviews, it seems that many people pay outsize attention to the landscape, while ignoring the sky. But since all the components of an image need to work together, the way you handle the sky is just as important as the way you handle the landscape that you’re most likely there to photograph.

From rainbows, to dramatic clouds, to vivid sunrises and sunsets, great skies are easy, regardless of the landscape. But what do you do when the sky is bland and boring? The rule of thumb I’ve always followed and taught is that amount of sky you put in an image should be based on the relative appeal of the sky versus the landscape: determine which has the most visual appeal and by how much, then allocate your frame’s sky/landscape real estate percentage accordingly. I’m not suggesting that you whip out a calculator and do actual math in the field, but you get the idea.

Every autumn I visit North Lake, east of Bishop in the Eastern Sierra, hoping to catch the peak fall color there. Prepping for this post, I started reviewing my North Lake images from the 20 or so years that I’ve been visiting, and was immediately struck by the variety of the images taken from more or less the same location (somewhere along a 50-foot stretch of shoreline). The variety is both in the compositions and the conditions, but the compositions are largely determined by those conditions.

The annual variables at North Lake include the state of the fall color in the aspen across the lake (early, late, peak), the reflection (from serene mirror to windy chop), the level of the lake (and the rocks that are visible), the clouds and color in the sky, and the crowds (how much freedom is there for me and my workshop group to set up where we want).

Here’s a handful of North Lake images captured over the years. Without plunging too deep into the weeds, it’s pretty clear to me how the conditions on each day influenced my composition and exposure decisions.

Autumn Symmetry, North Lake, Eastern Sierra

The morning I captured the image I share today was impacted by a combination of scene variables, some positive, others negative. On the positive side, the color was as good as good as it can get there, and the reflection was really nice all morning. On the negative side, despite arriving an hour before sunrise, there were already a number of cars in the parking lot, which I knew would mean my group and I would be settling for whatever spaces were available, as well as limited ability explore (giving up a nice spot to search for something better risks finding nothing, while losing the nice spot you just left). And the sky sucked. (If you know me at all, you know that means there were no clouds.)

Rather than take the easy path up the road directly to the lakeshore (no more than 100 yards from the parking lot), I guided my group into the woods and along the creek to the lake—no farther, but the trail was a little muddy and slightly overgrown in spots. My rationale was that, since the most popular spots to set up were likely taken, this route would let them see that there are other very nice options that most visitors never make it to.

At the lake I found enough room for several in my group to set up in the “popular” area with the foreground rocks, and guided the rest just a few feet farther to a somewhat sheltered mini-cove on the other side of a large boulder. Just because the other spot is more popular doesn’t mean it’s better—this second spot, being more sheltered, means it’s more likely to have a reflection, even when the rest of the lake is shuffled by a breeze, and the foreground tall (and photogenic) grass aligns nicely with the peaks (the Autumn Morning, North Lake, Eastern Sierra image in the gallery above was taken from this spot).

Once everyone in my group was set up and happy, I squeezed into a remaining opening at the small reflective cove and went to work. In the fading twilight, I started to work out a plan, quickly deciding that this morning I would not take a single picture that includes the sky. This isn’t the approach I’d recommend for first-time North Lake visitors because excluding all of the sky also means excluding the beautiful peaks surrounding the lake. But I have so many images of the peaks here, many with much nicer skies, and didn’t really feel like I needed any more.

So I had a blast all morning playing with a variety of compositions that completely ignored the sky, ending up with about 2 dozen images to choose from when I got home. Below are the Lightroom thumbnails from that morning. (You can see that while I didn’t include the sky or peaks, more than half of the morning’s captures did include their reflections)

Not only do the Lightroom thumbnails show my compositional options this morning, they also reveal a little of my process. In general, my first capture is a “proof of concept,” and if I like what I see I start making refinements until I’m satisfied. And even though some of these thumbnails look identical, I can assure you that each one is at least a slight adjustment of the one preceding it.

I chose the composition I share today because I love the symmetry, the strong diagonals, and the way it emphasizes my favorite features of this beautiful little lake—but nothing else.

I return to the Eastern Sierra and North Lake next fall

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

No Sky, No Problem…

Eastern Sierra Love

Posted on October 5, 2024

I just returned last night from my annual Eastern Sierra autumn trip. Each time I’m there, I marvel at not just the quality of the scenery east of the Sierra Nevada, but even more impressive to me is the variety of the scenery. I’ve always believed if America could do it all over again and allocate it’s national parks before a varied assortment of land ownership and water rights entangled the land here, the Eastern Sierra would hands-down be one of America’s national park gems. But given the crowds clogging our national parks, and the relative quiet of the Eastern Sierra region, maybe the current situation is for the best.

Known more for the beauty of its serrated peaks, tumbling creeks, and placid lakes, the Eastern Sierra is also home to a small handful similarly beautiful, but far less heralded, waterfalls. Of these, without a doubt my favorite is Lone Pine Creek Fall, just above the parking area at the end of Whitney Portal Road. Stair-stepping down nearly vertical granite, Lone Pine Creek Fall flows year-round. Beautiful in any season, I’ve always been partial to autumn here, when I can catch the brief window when the fall is framed by an assortment of deciduous trees and shrubs. I always right around October 1, which puts me comfortably in the fall color window—sometimes slightly before peak, sometimes a slightly after, but always (so far) with enough color to enhance my images.

Turns out this year’s visit perfectly nailed the peak color. The color was so nice that, rather than settle for a variety of wide and telephoto compositions near the base of the fall, I took the time to scale the steep slope beside the fall in search of new perspectives. This wasn’t rock climbing, just a little extra effort in search of something different. Fortunately, I didn’t have to climb too far to find something I loved, because the climbing above this point would have been a lot more challenging.

I spend a lot of time encouraging my workshop students to build their images: identify strong visual elements, then to position themselves to create the best relationships connecting these elements. In this scene, in addition to the fall itself and the surrounding colorful leaves, I was drawn to the granite boulders beneath this section of fall, and the parallel curving trunks of the yellow trees to the right of the fall. And I was bothered by the bright sky visible just above the fall.

After considering both horizontal and vertical framing, I decided horizontal would be the best way to eliminate the bright sky while still including all the features I’d identified, without adding peripheral elements that dilute the image. To achieve the relationships and framing I wanted, and to avoid blocking the right side of the fall with a jutting branch, I moved as far to the left as I could safely (any farther left would have put me in the water on a 60-degree slick granite slope—splat!).

Given the falling water’s speed and the fact everything was in full shade, my only option for rendering the fall was some amount of motion blur. Lucky for me, the tendrils of water thinly spread across the fall created a lovely veil effect that (in my opinion) actually enhances the scene. And with objects near-to-far throughout the scene, I had to take special care with my focus point, choosing to focus on the closest foreground rock on the left to achieve sharpness throughout.

With my exposure and general framing set, I started working on micro-adjustments that led me to this image: specifically, making sure I didn’t cut off any of the large curved stick on the far right, the foreground rocks directly in front of me, and any of the large rock on the left (that I focused on).

I’m never happier as a photographer than I am when photographing scenes like Lone Pine Creek Fall—scenes with a disorganized abundance of diverse ingredients that challenge me to apply my creative instincts to assemble into something coherent and appealing. The Eastern Sierra offers something like this pretty much every direction I turn. A few years ago I wrote an article for Outdoor Photographer magazine (RIP) highlighting the many joys of photographing the Eastern Sierra’s diverse scenery, then turned a version of that article into a Photo Tips article here on my blog. I’ve spent a little time today updating the article while this week’s trip is still fresh in my mind, and am sharing it below. (And will soon be updating it in my Photo Tips section.)

Photograph the Eastern Sierra

Skirting the east side of the Sierra Nevada, US 395 enchants travelers with ever-changing views of California’s granite backbone. Unlike anything on the Sierra’s gently sloped west side, US 395 parallels the range’s precipitous east flank in the shadow of jagged peaks that soar up to 2 miles above the blacktop. More than just beautiful, these massive mountains form a natural barrier against incursion from the Golden State’s major metropolitan areas, keeping the Eastern Sierra region cleaner and quieter than its scenery might lead you to expect.

It would be difficult to find any place in the world with a more diverse selection of natural beauty than the 120-mile stretch of 395 between Lone Pine and Lee Vining: Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, the ancient bristlecones of the White Mountains (east of the Sierra, across the Owens Valley), the granite columns of Devil’s Postpile, Mono Lake and its tufa towers, and too many lake-dotted, aspen-lined canyons to count. Long a favored escape for hikers, hunters, and fishermen, in recent years photographers have come to appreciate the rugged, solitary beauty possible only on the Sierra’s sunrise side.

I prefer photographing most Eastern Sierra locations at sunrise, when the day’s first rays paint the mountains with warm light, and the highest peaks are colored rose by alpenglow. (Without clouds, Eastern Sierra sunset light can be tricky, as you’ll be photographing the shady side of the mountains against the brightest part of the sky.) Devoid of large metropolitan areas, minimal light pollution also makes the Eastern Sierra one California’s finest night photography destinations. But regardless of the time of day, the key to photographing the Eastern Sierra is flexibility—if you don’t like the light in one direction, you usually don’t need to travel far to find something nice in another direction.

Lone Pine area

The southern stretch US 395 bisects the Owens Valley, a flat, arid plane separating the Sierra Nevada to the west from the Inyo ranges to the east. Just west of Lone Pine lies the Alabama Hills. Named for a Confederate Civil War warship, the Alabama Hills’ jumble of weathered granite boulders and proliferation of natural arches would be photogenic in any setting. Putting Mt. Whitney (the highest point in the 48 contiguous states), Lone Pine Peak (the subject of Mac OS X Sierra’s desktop image), and the rest of the serrated southern Sierra crest seems almost unfair.

The Alabama Hills are traversed by a network of unpaved but generally quite navigable roads. To get there, drive west on Whitney Portal Road (the only traffic signal in Lone Pine). After 3 miles, turn right onto Movie Road and start exploring. If you’re struck by a vague sense of familiarity here, it’s probably because for nearly a century the Alabama Hills has attracted thousands of movie, TV show, and commercial film crews.

Mobius Arch (also called Whitney Arch and Alabama Hills Arch) is the most popular photo spot in the Alabama Hills. It’s a good place to start, but settling for this frequently photographed subject risks missing numerous opportunities for truly unique images here. To get to Mobius Arch, drive about a mile-and-half on Movie Road to the dirt parking area at the trailhead. Following the marked trail down and back up the nearby ravine, the arch is an easy ¼ mile walk. There’s not a lot of room here, but if the photographers work together it’s possible to arrange four or five photographers on tripods with Mt. Whitney framed by the arch. And don’t make the mistake many make: the prominent peak on the left is Lone Pine Peak; Mt. Whitney is serrated peak at the back of the canyon.

Sunrise is primetime for Alabama Hills photography, but good stuff can be found here long before the sun arrives. I try to be set up 45 minutes before the sun (earlier if I want to ensure the best position for Whitney Arch) to avoid missing a second of the Sierra’s striking transition from night to day.

The grand finale from anywhere in the Alabama Hills is the rose alpenglow that colors the Sierra crest just before sunrise. Soon after the alpenglow appears, the light will turn amber and slowly slide down the peaks until it reaches your location, warming the nearby boulders and casting dramatic, long shadows. But unless there are clouds to soften the light, you’ll find that the harsh morning light will end your shoot pretty quickly once the sunlight arrives on the Alabama Hills.

Whitney Portal Road (closed in winter) ends about 11 miles beyond Movie Road, at Whitney Portal, the trailhead for the hike to Mt. Whitney and the John Muir Trail. On this paved but steep road, anyone not afraid of heights will enjoy great views looking east over the Alabama Hills and Owens Valley far below, and up-close views of Mt. Whitney looming in the west. At the back of the Whitney Portal parking lot is a nice waterfall that tumbles several hundred feet in multiple steps.

The Alabama Hills are one of my favorite moonlight locations. Because the full moon rises in the east right around sunset, on full moon nights the Alabama Hills and Sierra crest are bathed in moonlight as soon as darkness falls. Lit by the moon, the hills’ rounded boulders mingle with long, eerie shadows, and the snow-capped Sierra granite radiates as if lit from within.

If you find yourself with extra time, drive about 30 miles east of Lone Pine on Highway 136 until you ascend to a plain dotted with photogenic Joshua trees—after you’ve finished photographing the Joshua trees, turn around and retrace the drive back to Lone Pine on 136 to enjoy spectacular panoramic views of the Sierra crest. And just north of Lone Pine on 395 is Manzanar National Historic site, a restored WWII Japanese relocation camp. Camera or not, this historic location is definitely worth taking an hour or two to explore.

Bristlecone pine forest

Continuing north from Lone Pine on 395, on your left the Sierra stretch north as far as the eye can see, while the Inyo mountains on the right transition seamlessly to the White Mountains. Though geologically different from the Sierra, the White Mountains’ proximity and Sierra views make it an essential part of the Eastern Sierra experience.

Clinging to rocky slopes in the thin air above 10,000 feet, the bristlecone pines of the White Mountains are among the oldest living things on earth—many show no signs of giving up after 4,000 years; at least one bristlecone is estimated to be 5,000 years old.

Abused by centuries of frigid temperatures, relentless wind, oxygen deprivation, and persistent drought, the bristlecones display every year of their age. Their stunted, twisted, gnarled, polished wood makes the bristlecones suited for intimate macros and mid-range portraits, or as a striking foreground for a distant panorama.

The two primary destinations in the bristlecone pine forest are the Schulman and Patriarch Groves. Get to the bristlecone pine forest by driving east from Big Pine on Highway 168 and climbing about 13 car-sickness inducing miles. Turn left on White Mountain Road and continue climbing another 10 twisting miles to reach Schulman Grove. Despite the incline and curves, the road is paved all the way to this point. A couple of miles before reaching Schulman Grove I recommend stopping at the breathtaking Sierra panorama—in addition to the spectacular view, it’s a great opportunity to pause, collect yourself, and maybe let your car-sickness subside.

Stop at the small visitor center in the Schulman Grove to pay the modest use fee, then choose between the 1-mile Discovery loop trail, and the 4 1/2 mile Methuselah loop trail. Both trails are in good shape, but the extreme up and down in very thin air will test your fitness. Most of the trees on the Methuselah Trail get more morning light, while the majority of the Discovery Trail trees get their light in the afternoon.

If you’re unsure of your fitness, or have limited time, the Discovery Trail is definitely the choice for you. Because the photogenic trees start with the very first steps (if you go the recommended counter-clockwise direction), on this trail you can turn around at any point without feeling cheated of opportunities to photograph nice bristlecones. And along the way you’ll appreciate the handful of benches for enjoying the view and catching your breath. Hikers who can make it to the top of the switchbacks are rewarded great views of the snow-capped Sierra across the Owens Valley.

The Discovery Trail climbs for a couple hundred more yards beyond the switchbacks, but just as you’re beginning to wonder whether all the effort is worth it, the trail levels, turns, and drops. Soon you’ll round a 90-degree bend and be rewarded for your hard work with two of the most spectacular bristlecones in the entire forest. Spend as much time here as you have, because the rest of the loop back to the parking lot has nothing to compete with these two trees.

The pavement ends at the Schulman Grove, but the unpaved 12-mile drive to the Patriarch Grove is navigable by all vehicles in dry conditions. Home to the Patriarch Tree, the world’s largest bristlecone pine, the Patriarch Grove is more primitive and much less visited than the Schulman Grove. Unlike the Schulman Grove, where I rarely stray far from the trail, I often find the most photogenic bristlecones here by venturing cross-country, over several small ridges east of the Patriarch Tree. Even without a trail, the sparse vegetation and hilly terrain provides enough vantage points that make getting lost difficult.

Clean air, few clouds, and very little light pollution make the bristlecone groves a premier night photography location. On moonless summer and early autumn nights, the bright center of the Milky Way is clearly visible from the slopes of the bristlecone forest. For the best Milky Way images, look for trees that can be photographed against the southern sky. And no matter how warm it is on 395 below, pack a jacket.

The bristlecone forest closes in winter.

Bishop area

An hour north of Lone Pine on 395 is Bishop. Its central location, combined with ample lodging, restaurant, and shopping options make Bishop an excellent hub for an Eastern Sierra trip—if you want to anchor in one spot and venture out to the other Eastern Sierra locations, Bishop is probably your best bet.

West of Bishop are many small but scenic lakes nestled in steep, creek-carved canyons that are lined with aspen (and some cottonwood) that turn brilliant yellow each fall. Many of these canyons can be accessed on paved roads, others via unpaved roads of varying navigability, and a few solely by foot.

Of these canyons, Bishop Creek Canyon is the best combination of accessible and scenic. To get there, drive west on Highway 168 (Line Street in Bishop). After about 15 miles you can decide whether to turn left on the road to South Lake, or continue straight to reach North Lake and Lake Sabrina (pronounced with a long “i”).

One of the area’s most popular sunrise spots, North Lake is a 1-mile signed detour on a narrow, steep, unpaved road—easily navigated in good conditions by all vehicles, but the un-railed, near vertical drop is not for the faint of heart. A mile or so beyond the turn to North Lake the road ends at Lake Sabrina, a fairly large reservoir in the shadow of rugged peaks and surrounded by beautiful aspen (but its bathtub ring when less than full is not for me).

South Lake is another aspen-lined reservoir that shrinks in late summer and autumn. Highlights on South Lake Road are a manmade but photogenic waterfall leaping from the mountainside, clearly visible on the left as you ascend, and Weir Lake, just before South Lake.

Both Bishop Canyon roads are worth exploring, especially in autumn, when the fall color can be spectacular. Each features scenic tarns and dense aspen stands accented by views of nearby Sierra peaks. Rather than beeline to a fall color spot, in autumn I drive the Sabrina and South Lake roads and pick the best color.

Highway 395 north of Bishop features a few of my favorite fall color destinations, including Rock Creek Canyon and McGee Creek. About a half hour north of Bishop, detour west off the highway to postcard-perfect Convict Lake. And just beyond the road to Convict Lake is the upscale resort town of Mammoth Lakes, just a few miles west of 395. The drive on 203 through Mammoth Lakes takes you past the Mammoth Mountain Ski slopes to Minaret Vista. This panoramic view of the sawtooth Minaret Range, Mt. Ritter, and Mt. Banner captures the essence of high Sierra beauty. From here, follow the road down the other side to see the basalt columns of Devil’s Postpile, and to take the short hike to Rainbow Fall.

Lee Vining area

Leaving Bishop, Highway 395 climbs steeply, crests near Crowley Lake, skirts the communities of Mammoth Lakes and June Lake, finally dropping down into the Mono Basin and Lee Vining. Though this is an easy, one-hour drive, you’ll feel like you’ve landed on a different planet. In October, detour onto the June Lake Loop, another popular fall color drive.

By far the most popular Mono Lake location is South Tufa, a garden of limestone tufa towers that line the shore and rise from the lake. Tufa are calcium carbonate protrusions formed by submerged springs and revealed when the lake drops. In addition to the striking tufa towers, South Tufa is on a point that protrudes into the lake, allowing photographers to compose with both tufa and lake in the frame while facing west, north, or east.

To visit South Tufa, turn east on Highway 120 about 5 miles south of Lee Vining. Follow this road for another 5 miles and turn left at the sign for South Tufa. Drive about a mile on an unpaved, dusty but easily navigated road to the large dirt parking lot. From here it’s an easy ¼ mile walk to the lake, but wear your mud shoes if you want to get close to the water. And don’t climb on the tufa.

While South Tufa can be really nice at sunset, mirror reflections on the frequently calm lake surface, and warm light skimming over the low eastern horizon, make this one of California’s premier sunrise locations. To get the most out of a sunrise shoot here, it’s a good idea to photograph South Tufa at sunset to familiarize yourself with the many possibilities here (and who knows, maybe you’ll get lucky and catch one of the Eastern Sierra’s spectacular sunsets).

In the morning, arrive at the lake at least 45 minutes before sunrise to ensure a good spot at this popular location—you can start shooting as soon as you arriving, using long exposures to brighten the scene and smooth the water. I usually start with scenes to the east, capturing tufa silhouettes against indigo sky and water. As the dawn brightens, keep your head on a swivel and be prepared to shift positions with the changing light.

As the sun approaches and the dynamic range increases in the east, I often turn to face west. Soon the highest Sierra peaks are colored with pink alpenglow, followed quickly by the day’s first direct sunlight. With the sun rising beneath the horizon behind me, its light slowly descends the Sierra peaks stretching before me. When the sunlight finally reaches lake level, for a few minutes the tufa towers are awash with warm sidelight, creating wonderful opportunities facing north. As with the Alabama Hills, without clouds to soften the sunlight and make the sky more interesting, the sunrise show is terminated quickly by contrasty light.

Other options in and near Lee Vining are the excellent Mono Lake visitor center on the north side of town, the small but very informative Mono Committee headquarters in the middle of town, any meal at the Whoa Nellie Deli in the Mobil Station (trust me on this), and Bodie, an extremely photogenic ghost town maintained in a state of arrested decay, less than an hour’s drive north. And a sinuous 20-minute drive west, up 120 (closed in winter) lands you at Tioga Pass, Yosemite’s east entrance and the gateway to Tuolumne Meadows.

Fall color in the Eastern Sierra

Each fall the Eastern Sierra becomes a Mecca for photographers chasing the vivid gold coloring the area’s ubiquitous aspen groves. The show starts in late September at the highest elevations, and continues well into October in some of the lower elevations. Fall color timing and locations vary from year-to-year, but the general fall color rule to follow here is: If the trees are still green, just keep climbing.

The best way to photograph the Eastern Sierra’s fall color is to explore: Pick a road that heads west and start climbing until something stops you. To give you a head start, here are a few of my favorite spots, from south to north. (Rather than beeline to specific locations in these ever-changing canyons, I’ve found it’s best to drive slowly and stay alert for opportunities along the way.)

Bishop Creek Canyon: Nice any season it’s open, Bishop Creek Canyon (detailed earlier) comes alive with gold each autumn. Aspen surrounding the canyon’s many lakes make for spectacular reflections. Of these, North Lake is probably the most popular, but autumn mornings can be extremely crowded here. The color in Bishop Creek Canyon usually peaks in late September at the highest elevations (near North Lake, Lake Sabrina, and South Lake), but lasts until mid-October farther down the canyon.

Rock Creek Canyon: Near the crest of the climb out of Bishop on 395, turn left at the sign for Rock Creek Lake. Climb this road along Rock Creek all the way up to its terminus at Mosquito Flat trailhead. Over 10,000 feet, this is the highest paved road in the Sierra. As with Bishop Creek Canyon, the best photography in Rock Creek Canyon is usually found at random points along the road—drive slowly and keep your eyes peeled.

McGee Creek: When you see Crowley Lake on the right, look for the road to McGee Creek on the left. This 2-mile unpaved road is navigable by all vehicles, but take it slow. It ends at a paved parking lot that’s the launching point for a hike up McGee Creek, into the canyon, and the mountains beyond. Unlike most other Eastern Sierra canyons, the dominant tree here is cottonwood. While I’ve had good success photographing along the creek right beside the parking lot, you can find nice color as far up the canyon as your schedule (and fitness) permits.

Convict Lake: The road to Convict Lake is just south of Mammoth Lakes. It’s a 2-mile paved drive to a beautiful lake nestled at the base of towering mountains—definitely worth the short detour off of 395.

June Lake Loop: Between Mammoth Lakes and Lee Vining is a 15 mile loop that exits 395 near the small town of June Lake (look for a gas station on the left) and returns to 395 a few miles down. Along the route you’ll find several lakes, and a waterfall at the very back of the loop (visible from the road).

Lundy Canyon: About 5 miles north of Lee Vining, turn left onto the Lundy Canyon road to enjoy one of my favorite Eastern Sierra fall color spots. The lower half of this road, below Lundy Lake, is often a good place to find late season color, but my favorite photo spots aren’t until road turns bad, just beyond the lake.

Driving slowly and with great care, most vehicles can make the 2 unpaved miles along Mill Creek to the end of the road. In addition to beautiful creek scenes, you’ll find several small, reflective beaver ponds along the way. If you make it to the end of the road, park and follow the trail up the canyon, through an aspen grove, for about ¼ mile to reach a small, waterfall-fed lake. The overgrown lakeshore makes photography here difficult, but a short walk along the shoreline to the left, toward the lake outlet, will take you to a massive beaver dam. Roll up your pants and get your feet (and more) wet for the best views of the lake.

Dunderberg Peak and Virginia Lakes: Shortly after the turn to Lundy Canyon, 395 climbs steeply to Conway Summit, at 8143 feet, it’s the highest point on the entire route. On the left, just past a spectacular view of the entire Mono Basin (worth the stop), is the road to Virginia Lakes. Here you’ll find some of the area’s earliest aspen to turn. Just beyond the Virginia Lakes road are colorful views of Dunderberg Peak and its aspen-blanketed slopes.

Let me share the joys of the Eastern Sierra with you next fall

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

An Eastern Sierra Gallery

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

The Method To My Madness

Posted on September 28, 2024

Last Saturday I did a Zoom presentation for a camera club in Texas. My topic was seeing the world the way your camera sees it, a frequently recurring theme for me, but preparing for and delivering this presentation put it in the front of my mind as I processed this image from my recent Hawaii Big Island workshop.

Most of us know the feeling of coming across a scene that moves us to photograph it. And now that we all carry around powerful, pocket-size cameras, never has it been easier to fulfill that urge. For some, it’s enough to merely snap a quick shot that saves the memory—even if you never look at that picture again (many won’t), there’s genuine comfort in the knowledge that you can revisit that memory any time you want to.

For others, professional and closet photographers alike (if you can’t help pausing to photograph something that excites you, and aren’t satisfied until that photo is just so, you might be a photographer and not even know it), it’s important to convey something of the experience of being there, or the specialness that moved you to stop and pull out your camera. But if your results matter that much, you also know the feeling of disappointment when revisiting or sharing an image of an especially beautiful scene, only to find that it somehow fails to generate the enthusiasm you felt being there.

Disappointing results usually happen when we fail to fully appreciate that the camera sees the world differently than we do, and therefore fail to take the camera’s (from smartphone to large format) unique vision into account when crafting our image. So I thought I’d share my process in creating this Onomea Falls image from my recently completed Hawaii workshop, and how I attempted to leverage my camera’s vision to get the most from the scene.

I’ve visited the Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden dozens of times in the 15 or so years I’ve been photographing Hawaii’s Big Island. From our hotel in Hilo, it’s just a 20 minute drive that winds along an wonderfully lush road. How lush? When the property that was to become the garden was purchased by Dan and Pauline Lutkenhouse in 1977, they didn’t even know it had a waterfall.

For the next 7 years, Dan and one helper labored with nothing but hand tools to clear dense foliage and carve paths in the hard black basalt, toiling 7 days a week until the garden was ready to open. Of course the work wasn’t done then, and in fact managing the dense, fast growing plants remains a year round effort. Dan passed in 2007, but the love that guided his meticulous care lives on, and is clearly visible in the garden’s every square inch.

The crown jewel of HTBG is Onomea Falls. Originating on the slopes of Mauna Kea, Onomea Stream stair-steps its way through the garden, forming one of the most beautiful waterfalls on the entire island. I’ve always been drawn to the tumbling water and lush foliage of Onomea Falls, and every time I visit work hard to overcome the challenges of photographing it. Some visits I succeed more than others, often getting “nice” images (it’s hard to go wrong here), but rarely getting something that thrills me.

This year I vowed to change that.

First, I’ll say a few words about the differences between camera and human vision that applied to this scene:

- Dynamic range: The dynamic range of digital sensors improves each year, but has not yet gotten close to human vision. Often shadow detail clearly visible to our eyes is rendered black in an image exposed to spare brilliant highlights; or clearly visible highlight detail is rendered white when we expose for the shadows. The problem is especially difficult when a densely shaded scene contains splashes of brilliant sunlight. There are many ways to overcome dynamic range shortcomings, such as blending multiple images (which I never do) or neutral density filters (which I rarely use anymore, and are useless in a shaded scene with random sunlight anyway). Complete shade is the great dynamic range equalizer, and I always try to photograph flowing water like Onomea Falls in overcast or full shade to soften the light and significantly reduce the scene’s dynamic range.

- Missing dimension: Photography attempts to render a 3-dimensional world in a 2-dimensional medium. And while that’s impossible, what is possible is creating the illusion of depth by ensuring that my composition has elements that draw or guide the eye throughout. Onomea Falls’ descending stair-step layout, and abundant surrounding plants, provide ample opportunity to create the depth illusion I seek.

- Depth of field: The human eye quickly adjusts focus from near to far, allowing us to view every aspect of the world in sharp focus (virtually) at once. While the camera can often achieve front-to-back focus throughout an entire scene, there are limitations to this capability, and achieving it often requires great care. That’s especially true in a scene like this, where I have important visual elements from just a few feet away all the way to the top of the hill at the back of the scene.

- Constrained view: While the human experience of any scene is 360 degrees and multi-sensory, a still image is always constrained by a rectangular box. Using a wide angle lens will include more of the world, but also shrinks everything in the scene. There’s a lot going on at this Onomea Falls view, and deciding what to include and exclude is an important part of the creative process here.

- Motion: Like photography’s missing dimension, our world’s continuous motion is impossible to duplicate in a still photo. The best we can hope to do is convey a sense of motion with our shutter speed choice. Of course many landscape scenes are completely stationary, rendering the motion problem irrelevant, but that isn’t the case at Onomea Falls, where the water’s motion is the scene’s primary focal point.

The afternoon I brought my group to the botanical garden was a mixture of clouds and sunlight. Since it was fairly cloudy when we arrived, I actually started here and got in a few frames with nice light before the direct sunlight returned. But it wasn’t until I returned at the end of our visit, once the sun had gone behind the hill above the fall, that I got the complete shade I wanted.

But that first visit wasn’t a complete loss because it gave me the opportunity to spend quality time with the scene and identify an approach for when I returned later. First and foremost, I wanted to take advantage of all the beautiful visual elements throughout the scene. I’ve always loved the lush, verdant feel down here, and found myself especially drawn to the moss-covered rock (in hindsight, this also could be an old tree stump—I have to remember to check the next time I’m there—but for now I’m going with rock) smothered in a variety of tropical plants right on the other side of the vista’s railing.

I decided to go for a wide composition using my 16-35 f/2.8 lens, putting the foreground plants front and center while shrinking Onomea Falls enough that the plants became the scene’s focal point. As I said earlier, there’s a lot going on in this scene, so even after my general decision to feature the nearby plants and shrink the fall, I still needed to determine what else to include and eliminate.

This is where the camera’s constrained view helps. I briefly considered a horizontal frame, but opted for a vertical frame that allowed me to excise lots of superfluous foliage around the perimeter, and minimize the relatively bland pool at the base of the fall, in favor of the scene’s most important elements: the foreground plant-covered rock and cascading Onomea Falls.

I knew that the lower and closer I got to the foreground plants, the more of my frame they would occupy. Getting my camera as low as possible required significant tripod contortions. I ended up with all three tripod legs splayed fairly wide—one on the pavement, one on the low wall (upon which the short rail was mounted), and one just out of sight among the plants. This put the closest plants about less than 3 feet from my lens.

I stopped down to f/16, framed up a general idea of what I was going for, and clicked. Each time I’d stand back to evaluate the latest result on my camera’s LCD, make small adjustments to my position and composition, and click again. My position relative to the various elements in my frame is key to the illusion of depth that’s so important, so my decision to reposition was solely based on the relationships the new position created, with special care taken to avoid merging elements at different distances (to the extent that was possible).

I ultimately ended up with this position because I liked the way the lowest section of the fall was framed with two fairly prominent bunches of leaves. I chose this camera height because any lower would have merged the fall with the foreground foliage, while higher created an unnecessary empty zone between the foliage and fall. (In a perfect world that small fern frond wouldn’t jut up into the bottom of the fall, but the world is rarely perfect.)

Through this click, evaluate, refine process, I took half dozen or so “draft” frames before I was satisfied with the overall relationships. Next I zeroed in on the important micro-elements in my frame, identifying how the various elements move the eye, and checking my borders to minimize potential distractions that might invite the viewer’s eye out of the frame. For example, I took great care not to cut off either of the framing leaf groups with the frame’s border. And at the bottom of the frame, while I knew I’d be cutting off something, I chose a spot that allowed me to include some of the nicely textured moss and a couple of red ferns, without cutting of the most prominent leaves.

The longer I worked the scene, I more I became aware that just above the fall, the foliage opened up and brightened quite a bit. Rather than hinting at the world beyond my scene, I chose to put the top of my frame just below the point where the foliage thinned out, creating the illusion that this lush world might continue for miles up the mountainside.

With my composition worked out, the next piece of the puzzle was ensuring front-to-back sharpness. My focal length was around 24mm, making my hyperfocal distance at f/16 around 4 feet (I verified this on my DOF app). But the hyperfocal point is an approximation based on “acceptable” sharpness (a notoriously fickle target based on an arbitrary definition of “acceptable”). In this case, I focused on the farthest of the foreground leaves (atop the rock), which I guessed were about 5 feet away. I chose to focus beyond the hyperfocal point to ensure more sharpness at the back of the scene, and because focusing closer would have given me foreground sharpness I didn’t need.

And finally, I needed to decide on the motion effect I wanted. With the sun behind the mountain, this always inherently shady scene was especially dark. Adding to that was the fact that I needed f/16 for depth of field, so at any reasonable ISO, my choice was how much motion blur rather sharply frozen splashing water drops. At ISO 100, a multi-second exposure was no problem, but by increasing my ISO up to around 1600, in 1 stop increments, I gave myself a range of shutter speeds up to 1/4 second. All created some amount of blur, but after closely scrutinizing all my frames on my computer, I chose this one that used 1 second at ISO 400, because it retained very subtle texture in the rushing water. Much faster than 1 second created a little bit of scratchiness in the water that I didn’t like; longer than 1 second completely smoothed out the water’s texture.

I should also add that polarizing this scene was an essential component of the final result. Scenes like this are filled with reflective sheen on the water, leaves, and wet rock. Polarizing it significantly reduces that sheen, greatly enhancing the rich green.

This picture doesn’t reproduce exactly what my eyes saw, nor does it attempt to. But by staying true to what my camera saw, I was able to more clearly convey the scene’s lushness.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Lush

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Danger in Paradise

Posted on September 21, 2024

Battered for millennia by earthquakes, floods, volcanic eruptions, and tropical cyclones, it’s no wonder Hawaii’s residents keep one eye on the ocean, the other on the mountains—all while closely monitoring the sky overhead. I’ve visited each of Hawaii’s major islands many times (okay, so technically, on Oahu I haven’t been outside the airport, which is its own sort of disaster), and have personally experienced a veritable smorgasbord of these natural events. (Yet somehow I keep returning—go figure.)

The Hawaii earthquakes I’ve felt have been relatively minor jiggles to my earthquake-hardened California bones, but each served as a reminder that Hawaii has a history of large earthquakes, with magnitudes at least into the high 7s. Active volcanism makes the Big Island particularly vulnerable: as recently as 2018 it was shaken by a magnitude 6.9 earthquake; in 1975 a magnitude 7.7 quake rocked the Puna Coast just south and west of Hilo. Moving north, the Hawaiian Islands’ earthquake risk decreases: Maui has experienced a couple of magnitude 6 quakes in historic times (just offshore), while Oahu only gets a moderate jostling from time to time (but does get a pretty good jolt from the strongest Big Island quakes)—only Kauai, the oldest island, is (relatively) seismically stable.

Hawaii’s volcanoes are sexier than its earthquakes, actually attracting visitors (you don’t see too many people rushing toward an earthquake). I missed the recent Mauna Loa eruption, but have witnessed numerous Kilauea eruptions, in many forms: many time I’ve enjoyed standing on the rim at night to view the glow and smoke emanating from the lava lake bubbling just out of sight on the caldera floor far below; last year, I stood on the edge of (the recently seismically remodeled) Kilauea caldera with my workshop group and peered down at dozens of towering lava fountains less than a mile away. In 2010, Don Smith and I hiked close enough to a Kilauea lava flow that we felt its heat and heard trees explode. But despite their dramatic aesthetic appeal, Hawaii’s volcanoes are still too powerful to be taken lightly. While most of its eruptions lack the explosiveness of many more dangerous volcanoes around the world, as recently as 2018 Hawaii’s effusive lava flows have wiped out entire towns, destroying hundreds of homes on their way to the ocean.

And then there are the tropical cyclones that lash the islands several times each decade. By far the most significant storm damage to a Hawaiian island was inflicted by Hurricane Iniki in 1992, striking Kauai as a Category 4 storm with winds up to 140 miles per hour. While I’ve never experienced anything that extreme on my visits, in September of 2018, each of my two workshops was altered by a different hurricane: first on the Big Island when, a few days before that workshop started, a close brush with Category 5 Hurricane Lane deposited up to 58 inches of rain that flooded many of my locations. I departed Hawaii for Maui and my second workshop, only to have Hurricane Olivia (downgraded to a tropical storm just before landfall) force me to relocate the workshop’s two nights in Hana, and find replacement locations for those days.

I’ve also learned firsthand that it doesn’t take a hurricane to generate floods in Hawaii. In 2016 I was on Maui when just regular old torrential rainfall caused a 500-year flood in the Iao Valley and Central Maui, destroying homes and swamping cars. While driving through Central Maui after the water receded, I saw cars still mired in water to their doors.

Even given this history of disasters, compounded by my own personal experience with some of Hawaii’s most extreme natural elements, I would argue that Hawaii’s greatest natural risk is tsunamis. Despite their relative rarity, tsunamis have killed more people than all other Hawaiian natural disasters combined. The islands’ position smack in the middle of the Pacific Ring of Fire, which happens to be the source of nearly 3/4 of Earth’s tsunamis, means Hawaiians need to think in terms of when, not if, the next tsunami hits, and plan accordingly.

Unlike conventional waves, which are wind-generated and affect only the ocean’s surface, a tsunami is formed when a cataclysmic event displaces water from the ocean surface all the way down to the ocean floor. Potential ocean-moving events include submarine landslides, volcanic eruptions, and meteor impacts. But by far the most frequent force behind a tsunami is subduction earthquakes, when one tectonic plate thrusts beneath another and displaces the overlying plate and all the water above it.