Making lemonade at the Grand Canyon

Posted on April 30, 2012

We’ve all heard Dale Carnegie’s trite maxim, “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” Of course these pithy statements become popular because they resonate with so many people, photographers included. And it seems that not only are the photographers who adopt this attitude more productive, they’re just plain happier. For example….

Few pursuits are more frustrating than trying to predict Mother Nature’s fickle whims. Last week I was in Northern Arizona co-leading Don Smith’s Northern Arizona workshop. On our first night we pulled in to Desert View to find everything in place for a vivid, colorful, cliché Grand Canyon sunset: billowing cumulus clouds, patches of blue sky, and a gaping hole for the setting sun on the western horizon.

The only problem was, for some inexplicable reason, the color never materialized–the sun dropped, the light faded, and we were teased with no more than a few whispers of pink. For anyone who had put all their eggs in the brilliant sunset basket, this would have been a major disappointment. But (in my opinion) what we did get was even better.

Anticipating a colorful sunset, I had set up my composition accordingly. I was patiently waiting when, just before reaching the horizon, the sun slipped beneath a cloud and for about 90 seconds painted the canyon’s rim with the brightest, warmest light imaginable. When the light popped I quickly jettisoned my colorful sky composition and scanned the rim for a subject painted by the sunlight. When my eyes fell on this tree I quickly evaluated the scene for the best way to emphasize the tree and foreground light.

While the tree and light were front and center, the storm clouds overhead and Colorado River below made excellent background complements I knew I needed to include. I started by aligning myself with the tree’s branches framing the Colorado. Moving as far back as the terrain permitted, I zoomed to fill the frame and compress the foreground/background distance. With a 67mm focal length, depth of field was tricky. My hyperfocal app told me that the hyperfocal distance at f16 was around 30 feet, meaning if I focus 30 feet away, I could be sharp from 15 feet to infinity. I refined my composition, removed my camera from the tripod, focused on a tree about 30 feet away, returned the camera to the tripod, and clicked.

I’m a big advocate of surveying a scene, anticipating the light and conditions, and finding compositions before the conditions occur. But the moral here is to not become so locked in to a plan that you fail to seize unexpected opportunities. In hindsight I realize I should have anticipated this light too–I had a clear view of the sun’s path to western horizon, but I was so giddy with excitement about the color that was “sure” to materialize that I almost missed this other opportunity.

As it turned out, at Hopi Point the next evening we had the opposite experience–clouds on the western horizon promised to block the color-generating sunlight, but those of us who waited 15 minutes after sunset were (somehow) treated to a neon sunset that had the whole shuttle bus buzzing all the way back to the village (more on this in a future post). Maybe if I were as familiar with the Grand Canyon as I am with Yosemite, I’d be better at predicting its conditions, but until that happens, I’ll just keep guzzling the lemonade.

Looking a little closer

Posted on April 20, 2012

My print sales tell me that it’s the familiar, dramatic vistas that people are most interested in (not that there’s anything wrong with that), but what I most like photographing is the often overlooked details that make nature special. While I do my share of landscape retreads–because there are reasons these scenes are popular and I’m still a sucker for natural beauty–when left to my own devices, I could (and do) shoot stuff like this intimate Maui beach scene all day.

Because Maui and the Big Island have experienced the most recent volcanic activity (it’s ongoing on the Big Island), scenes like this are much more common than they are on the other major islands. I found these volcanic stones, polished smooth by sand and surf, on a small beach near Hana. I composed to capture the sea/land interaction that’s so easily overlooked in favor of the more dramatic surroundings. Once I found a composition I liked, I clicked twenty frames recording a variety of wave actions at different shutter speeds.

The best laid plans…

Posted on April 13, 2012

Red Veil, Bridalveil Fall and the Merced River Canyon, Yosemite

The plan was to photograph a full moon rising at the end of the Merced River Canyon, just to the right of Bridalveil Fall, at sunset. It was the final night of last week’s Yosemite Spring: Moonbow and Wildflowers photo workshop, and the moonrise was to be the grand finale. But after a day photographing poppies and waterfalls beneath a sky mixed with sun and clouds, the clouds took over and threatened to obscure everything. Nevertheless, most of the group hung in there to the bitter end, which is how we found ourselves at this vista point on Big Oak Flat Road about 45 minutes before sunset.

We could see Bridalveil but no hint of sky anywhere. Along with the clouds had come a biting cold (for April) wind that included a few snowflakes–most of the week and been quite comfortable, so we were a little unprepared for (and resentful of) the change. But there we stood, cameras poised atop tripods, shivering (us, not the cameras), chatting, and monitoring the horizon for any sign of an opening. I gave my standard “It’s impossible to predict Yosemite’s conditions in five minutes based on the conditions now” speech (it’s true), but the clouds were clearly lowering and even I was secretly pessimistic.

About the time people started eyeing the warmth of the cars, a small patch of light appeared in front of Bridalveil. Given the absolute grayness of the sky, we were a little perplexed, but that didn’t keep anyone from engaging their camera and firing off a few quick frames before the light disappeared. And disappear it did, but only for a minute or so, before returning. After another minute or two it was clear that the light wasn’t shrinking, it was expanding and soon we all started rooting for it to spotlight Bridalveil (photographers are greedy).

Which is exactly what it did. For the next thirty minutes we were treated to a light show that defied explanation. From our perspective there was no break in the clouds, but clearly the sun must have slipped beneath an opening on the western horizon, out of site behind a granite ridge, because soon the shaft expanded to a focused beam that traversed the entire canyon. We’d been so focused on the light that we didn’t at first notice a translucent cloud that had broken away from the flat gray ceiling. As the invisible sun dropped toward the horizon, its light warmed to gold, the shaft ascending the canyon walls, eventually illuminating the sky above Bridalveil. For the next ten minutes we watched the rogue cloud go from a brilliant amber to deep crimson veil draping the canyon.

About the time the color started reflecting in the Merced River far below, I noticed that we were all just standing shoulder-to-shoulder capturing pretty much the same thing, so I quickly moved about 20 feet down in search of a foreground. With the color peaking I managed a few wide frames, framing the Merced River and Bridalveil Fall with two nearby evergreens. After that the color faded quickly and we were all left wondering whether we’d imagined what we’d just seen. I’ve been photographing in Yosemite for my entire adult life and have never seen anything quite like this. I didn’t even think about the moon until it popped over a ridge about two hours later, on my drive home.

Poppies!

Posted on April 9, 2012

I love photographing poppies. Just sayin’…..

What is macro photography?

The generally accepted definition of a macro image is one in which the subject is at least as large on the sensor as it is in reality. When we photograph an expansive landscape, we’re cramming the entire scene (with the help of a carefully crafted lens) onto a 24mm x 36mm sensor (that’s 35mm full frame—digital cameras with “cropped” sensors have even less real estate to work with; medium format has more). But imagine your landscape includes a flower with a ladybug: As you zoom or move closer to the flower, everything gets larger as the amount of the scene you capture gets smaller. Pretty soon the flower occupies most of the frame, but it’s still not true macro. Not until the ladybug occupies the same amount of space on the sensor as it does on the flower do you have a true macro image.

A lens that doesn’t focus close enough to allow a 1:1 subject:sensor relationship is not a true macro. In fact, many camera manufactures will (deceptively) label a lens’s (or point-and-shoot camera’s) closest focus point as “Macro,” when what they really mean is just plain “close focus.” This blurring of the definition causes the macro label to be applied to many close focus images and creates confusion.

Macro in spirit

So, by the generally accepted definition, this poppy scene doesn’t qualify as “macro,” not even close. But in my mind it’s macro in spirit because when I photograph poppies I feel an exceptionally intimate relationship with my immediate surroundings. My goal in these pseudo-macro images is make you look closer than you might have had you been there, and to hold you entirely in the frame by eliminating any hint of the outside world from my composition.

An ocean of gold

In this case I was enjoying a hillside carpeted with poppies and a small sprinkling of other wildflowers. Below me was an steep, poppy-covered slope that dropped out of sight over a cliff that dropped onto the rocks of the Merced River’s south fork. Above me the poppies saturated the hillside for several hundred feet, eventually disappearing into the blue sky above the oak- and shrub-lined crest.

From my vantage point I felt submerged in an ocean of gold, but I knew that capturing the entirety of the scene with a camera was impossible. Instead, I dialed my 70-200 lens to 160mm to limit the boundaries of my frame and create the illusion of an infinite expanse of poppies. Selecting a single prominent poppy about eight feet away as the scene’s focal point, I experimented with a range of f-stops, seeking a depth of field wide enough to render a sharp strip of poppies and shallow enough to blur the closest foreground and most distant background flowers into smears of color. The large, bright LCD on my new 5D Mark III enabled me to evaluate each capture closely despite the full sunlight (something that would have been impossible on my 1Ds Mark III).

At the f-stop I ended up settling on, f8, the depth of field was only about four inches, giving me very little margin for error. Here again my new LCD saved the day–I switched to live-view mode, selected the poppy, and magnified 10x. A breeze that shifted from soft, to stiff, to (occasionally) calm required patience and forced me to bump to ISO 400 and click several frames to ensure that I had at least one frame with the poppy sharp. And processing this image was interesting–as often happens with sunlit poppies, the color was so brilliant that I needed to desaturate to achieve something credible.

One more thing

Macro/close photography magnifies everything. Not only is there virtually no margin for depth of field and focus-point error, frequent tight, awkward positions seem to expand exponentially all the standard frustrations of using a tripod. But the extremely narrow margin of error is exactly why I can’t imagine attempting macro work without a tripod.

I’m a tripod evangelist because I believe that an image is not simply a click, it’s a process: compose, expose, click, evaluate, refine, repeat. Refining and repeating a standard landscape without a tripod is difficult enough; with macro the minuscule tolerances make it nearly impossible.

Photographing this scene I clicked fifteen frames, each a slight variation (improvement) of the previous. For my initial composition I was contorted, cramping, nearly flat on the ground, my tripod legs awkwardly splayed. But once I had the starting composition I stood and stretched, then found a more comfortable position (on my knees) that gave me a clear view of my LCD. I could identify the tweaks for the next frame at my own pace, comfortable in the knowledge that my previous composition was waiting for me right there on the top of my tripod.

The Road to Hana

Posted on April 1, 2012

In my parents’ day, Maui’s “Road to Hana” was something to be achieved. Negotiating the narrow, undulating, muddy, potholed, serpentine, lonely jungle track was a badge of honor, something akin to scaling Everest or walking on the moon.

Today’s Hana road has been graded, paved, and widened just enough to accommodate a double yellow line that creates the illusion of space for one car in each direction. This sanitized road, now dubbed the “Hana Highway,” hosts a daily bi-directional swarm of tourists whose priorities range from not missing a single leaf, all the way to being the first to cross the finish line in Hana or back in Kapalua. Unfortunately, priorities (among other things) collide at each of the 56 bridges that, due to budget constraints, remain at their original one-lane width. Add to this mix laboring bicyclists, a sky that pinballs between blinding sunshine and windshield-obliterating downpour, an assortment of impatient and sometimes hostile locals (they’re the ones whose music you hear before their pickup rounds the turn), an occasional ten-wheel dump truck large enough to scrape roadside foliage with both mirrors, and random mongooses that pop from the jungle with Wac-A-Mole predictability, and navigating the Road to Hana feels more like a Hope/Crosby movie than a tropical vacation.

But one thing hasn’t changed: The Road to Hana experience remains a living embodiment of the tired axiom, “It’s not the destination, it’s the journey.” Hana itself is a pleasant, Hawaiian town with nice beaches and a small but eclectic assortment of restaurants and lodging. But with every hairpin turn or precipitous drop on the way there, you can’t help feeling that you’ve plopped into Heaven on Earth. The Hana road’s 50-plus miles alternate between dark, jungle tunnels and cliff-hugging ocean panoramas, punctuated by waterfalls (some of which start above you and complete beneath you, on the other side of the car), colorful foliage, and the constant potential for a rainbow. And oh yeah—banana bread. The best banana bread you’ve ever tasted. Still warm.

Sonya and I set out for Hana early Thursday morning—not quite as early as we’d planned, but we hoped early enough. Finding the first few miles beautiful and relatively easy going, we naively congratulated ourselves for our early start. But somewhere around mile-ten, as the curves tightened, the road shrank, and the photography improved, our pace slowed considerably and we found ourselves swept up in the tourist wave. Parking at every scenic turnout was a battle that often resulted in extremely, uh, “creative” solutions. Nevertheless, after a day packed with a year’s worth of scenery, we rolled into Hana at about 5 pm, equal parts exhausted and hungry.

Approaching Hana we’d glanced a sign for a restaurant called “Café Romantica,” offering “Gourmet, organic vegetarian food.” Since Sonya’s a vegetarian, and I don’t eat red meat, meals on the road are sometimes problematic and we were excited about the possibility of rewarding ourselves with a good meal. But the sign offered no specifics and despite our vigilance we found no hint of its existence anywhere.

Once we were comfortably ensconced in our (amazing) room, I pulled out my iPhone and looked up Café Romantica. I found it on Yelp, but no address, website, or phone number anywhere. The Yelp reviews were both amazing (nearly unanimous 5 stars) and intriguing (references to a truck beside the road and bizarre hours) enough that I knew we had to find it. Clicking the “Directions” link on Yelp returned a Google map with a dot on the road about ten miles south of town (in the opposite direction from which we’d arrived)–still no address, but at least solid clue.

In a perfect world we’d have taken an hour or so to clean up, enjoy the setting, and recharge after the drive, but one of the Yelp reviews warned the restaurant closes at 7:00, so we sucked it up and headed right back out. (This might be a good time to mention that the day prior Sonya and I had driven to the top of Haleakala. This is a harrowing drive in its own right, spiraling from sea level to over 10,000 feet in less than thirty miles. On the way down the mountain the brake warning light in our rental blinked on and off intermittently. And on the drive to Hana that morning, our tire pressure warning light had come on a couple of times.)

Twilight was fast approaching, but we felt confident in the Google map on my iPhone, with its bold red dot representing Café Romantica and a blue dot that perfectly pinpointed our location. I mean, even without an address, how hard could it be? Since there’s only one road in and out of town, I figured we’d just drive into the jungle until we found the restaurant where the dots meet.

I watched the road and the dashboard warning lights (so far so good), while Sonya monitored the dots, watching the blue dot inch closer to the red one far slower than we’d expected. It became immediately clear that the road out of Hana is even more challenging than the road into Hana. It’s narrower, shrinking to one lane for long stretches, and much rougher. And while the road into Hana seemed to be about 80-percent fellow gawking (but harmless) tourists, the only vehicles we encountered south of town were clearly locals who seemed to be enforcing their own secret roadway protocol, the prime principle being that, no matter what the hazard or consequence, we are to get out of their way.

About five miles (twenty minutes) into the jungle we rounded a particularly narrow corner to find ourselves headlights-to-headlights with a careening pickup who instantly opted for his horn instead of his brakes. After deftly braking and swerving, I glanced in the mirror and saw that pickup driver had finally discovered his brakes, and in fact had also stumbled upon his reverse gear and gas pedal and as accelerating back in our direction. I boldly applied the gas and disappeared around the next bend, then spent the next two miles with an eye on the mirror. (I’ll probably never understand that little encounter, but fortunately we never saw the guy again.) The road grew more remote with each turn, and we started imagining engine and tire noises–at one point I rolled down the window to see if I could figure out where that tire noise was coming from, but the road noise was drowned out by jungle sounds. My attention alternated between the road in front of us, the rearview mirror, and the dash, while Sonya kept a vigilant eye on the dots and we traded to “Deliverance” jokes to ease the tension.

By the time our dots merged, darkness was almost complete and we were pretty much resigned to the reality that our dinner plan had descended to wild goose chase status. According to Yelp, Café Romantica clings to a remote, vine-covered cliff about two hundred vertical feet above the Pacific—there’s not enough room there for a toaster, let alone an entire restaurant. But at that point we were just happy to find a place wide enough to turn around.

The drive back in the dark was less eventful (and no doubt due to my vigilant scrutiny, the previous day’s warning lights never did return), though at one point we were tailgated by a group of partying teenagers who pushed us along until I found a place wide enough to pull over safely. Needless to say, we were quite hungry by the time we rolled into town at around 7:30. Given Hana’s limited selection of restaurants, its reputation for shutting down early, and our specific culinary needs, we inventoried the food we had in the car and decided rice cakes, graham crackers, and fruit could get us to breakfast without starving.

About two blocks from our hotel a string of lights on the left caught my attention and I slammed on my brakes while my brain struggled to comprehend what I saw. Suspended above a small motorhome on an otherwise vacant lot was an awning with the words, “Café Romantica.” It was so close to our room that the walk there would have been shorter than the walk to our car had been. Besides a man putting away chairs and tables at the back of the property and a woman puttering inside the motorhome, we couldn’t see much activity. Nevertheless, I executed a quick u-turn and parked out front.

The motorhome had an attached awning covering a short counter with three or four stools. Behind a sliding window above the counter puttered the woman. I approached the window, crossed my fingers, and asked if they were still open. She shook her and apologized politely, explaining that she was almost out food. But as I started to summarize our futile hunt of the last hour she must have heard the desperation in my voice, because immediately her face warmed and she reassured us in a most maternal tone that she’d take care of us. She introduced herself as Lori Lee and asked where we were from.

About then another couple walked up, and rather than turn them away, Lori Lee rattled off to the four of us a handful of the most mouth watering, eclectic vegetarian entrées imaginable: rellenos, quiche, curry, …. She qualified each offering with the proviso that she only had one or two servings of each, but since they all sounded so good, the four of us had no problem negotiating who’d get what.

Lori Lee entertained us with friendly conversation as we sipped a wonderful soup (that also gave us great hope for what was to follow) she’d offered to hold us over until dinner was ready. Rather than make you watch me chew, I’ll just say that dinner was so good that we ordered dessert (something we never do), and even added one of her remaining entrees to-go for lunch the next day.

One of my tenets is that things always work out. I have to confess that our drive that evening severely tested my conviction, but without our little misdirection adventure, Sonya and I would have been deprived of probably the most memorable experience of our trip, and a restaurant experience I’ll never forget.

A few words about this picture

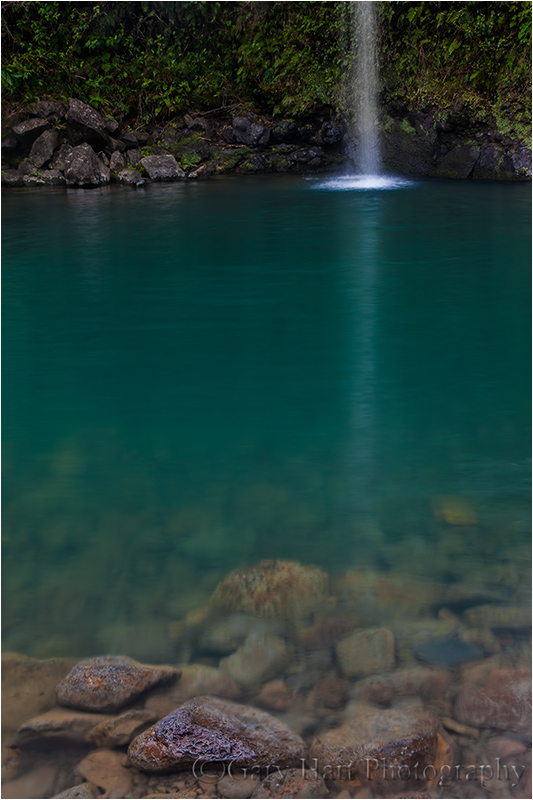

This little waterfall is just one of dozens visible along the entire length of the Hana Highway. Many are quite dramatic and stimulating; others, like this one, are more subdued and soothing. I must admit that by the time we pulled up to this fall I was verging waterfall overload. I’d found that my 70-200 lens worked best for most falls because it allowed me to isolate aspects of the scene and also to surgically remove tourists at some of the more popular falls, and I’d started exiting the car without the rest of my gear.

But cresting the small hill that provided a vantage point, I realized I’d left the car with only my 24-105 lens. Rather than walking back to the car (a hike all of maybe 150 feet), I decided to pick my way down to the pool’s edge. And had I not done that, I would have completely missed the beautiful rocks just beneath the water’s surface.

To ensure sharpness throughout the frame, I stopped down to f16, dropped to my knees, and focused on the large rock visible just beneath the surface (behind the protruding rocks). I carefully oriented my polarizer to remove glare on the nearby water and rocks, but not so much that I lost all of the fall’s reflection in the quiet water. I clicked several frames, all vertical. Some included the entire fall, but I like the mystery of this composition, the way it lets you imagine the rest of the fall and the scene surrounding it.

About thirty seconds after I snapped this a teenage girl jumped into the water right in front of me and the shot was gone. Fortunately I had all that I needed and I returned to the car a happy photographer.

Join me in my

Chomping at the bit

Posted on March 26, 2012

It’s been over a week since my last post. I have 350 Maui images on my hard disk, calling my name, but I’ve been so busy since coming home that I haven’t touched them. To give you an idea how busy I’ve been, last Tuesday my new 5D MarkIII arrived and I haven’t clicked the shutter once. That will change in a few days (if it kills me).

I love being a photographer, but it’s an unfortunate reality that turning your passion into your profession risks robbing photography of all the pleasure it once offered. Suddenly earning money takes priority over taking pictures, especially in this day when images just don’t sell the way they used to.

When I decided to make photography my livelihood, it was only after observing other very good digital photographers who, lured by the ease of digital photography, had taken the same path without recognizing that running a photography business requires far more than taking good pictures. Rather than becoming further immersed in their passion, they found themselves forced to photograph things not for love, but because it was the only way to put food on the table. And with the constant need for marketing, collections, bookkeeping, and just plain keeping customers happy, they soon realized that there was no time left to do what caused them to become photographers in the first place. Sigh.

So when I decided to change from photographer to Photographer, it was with a pretty good idea of what I was risking. I vowed that I’d only photograph what I want to photograph, that I’d never photograph something simply because I thought I could sell it. In my case that meant sticking landscapes: no people or wildlife–in other words, pretty much nothing that breathes.

But how to make money? My previous life in technical communications–I’d been a technical writer for a (very) large high tech company and before that had spent many years doing tech support, training, testing, and writing for a small software company–combined with a lifetime of camping, hiking, backpacking, and (of course) photographing throughout the American West, made conducting photo workshops a very easy (and enjoyable) step for me. Supplementing the workshops with writing and print sales has allowed me to pay the bills, visit the locations I’ve always loved, and explore new locations. And most importantly, it has allowed me to keep photographing only the things I love photographing.

One of the things I love photographing most is spring in Northern California. March is a month of bipolar weather swings, a time when blue skies with puffy clouds turn into gray, frog-drowning downpours with alarming suddenness. March is also when our hills reach a crescendo of pupil-dilating green, the oaks leaf out with new life, and poppies start to appear everywhere.

One of my favorite diversions on these spring afternoons is driving into the Sierra foothills east town to photograph the poppies. With the window down, Spring Training baseball on the radio (go Giants!), and doing my best to get lost in the maze of narrow, twisting foothill roads, I’m in photography heaven. I found the above scene a couple of years ago on a quiet hillside beside the Cosumnes River in the Gold Country of the Sierra foothills. But this scene could be just about anywhere in California’s ubiquitous rolling, oak-studded hills.

Despite the current busy schedule, there’s comfort in the knowledge that our spring conditions will persist into June. Next month I’ll find poppies and other wildflowers mixed with redbud in the many canyons roaring with Sierra snowmelt. And come May, it’s dogwood time….

Autumn Leaves (and winter arrives)

Posted on March 17, 2012

I’ve been in Maui since Monday (scouting for a new workshop), and despite the fact that there’s more to photograph here than there is time to photograph (seriously), I still find time to check the Yosemite webcams every day. In fact, even surrounded by all this tropical splendor, I’ll admit to a few pangs of homesickness when today’s webcams showed fresh snow, with more falling, in Yosemite Valley.

(I’ll get to my Maui pictures when I’m home, but until then here’s one from November.) At only 4,000 feet above sea level, Yosemite Valley is warm compared to most of the Sierra. It’s often raining here when it’s snowing just a little up the road. When it does snow in Yosemite Valley, for an hour or two scenes like this are quite common. But as soon as the sun comes out, the snow starts disappearing.

To see Yosemite Valley covered in white requires being there while it’s snowing–if you wait to leave until you hear it snowed in Yosemite, you’re too late. Photographing Yosemite while the snow is falling can be difficult, but the payoff is huge. Often the ceiling drops to the valley floor, obscuring everything that’s recognizable as Yosemite, but with the disappearing icons also vanishes the swarms of visitors and suddenly you feel like you’re alone in the world. Is there any silence more pure than the silence of falling snow?

The best nature photography often highlights the drama of change: the passing from day to night and back, the collision of ocean and land, an approaching or retreating storm. And, because it happens so gradually and only once each year, the movement from one season to the next is a rare photographic opportunity.

So that November morning my attention turned to shocked autumn leaves, lulled by weeks of benign fall weather, forced to cling to their colorful glory against winter’s sudden assault. After nearly a month as the main event, these leaves were lone survivors along a quiet bend in the Merced River. Within a couple days they no doubt fell to the forest floor, or were swept into the river, as inevitable winter prevailed.

Starry, starry night

Posted on March 14, 2012

Winter Star Trails, Half Dome and the Merced River, Yosemite

Canon 1Ds Mark III

28 mm

24 minutes

F/2.8

ISO 400

Yosemite is beautiful any time, under any conditions, but adding stars to the mix is almost unfair. I started doing night photography here on full moon nights about six or seven years ago, but recently I’ve enjoyed photographing the exquisite starscape of moonless Yosemite nights. With no moonlight to wash out the sky, the heavens come alive. Of course without moonlight visibility is extremely limited, and focus is sometimes an act of faith. But eyes adjust, and focus improves with experience (I promise).

After photographing, among other things, Yosemite Valley with a fresh blanket of snow and Horsetail Fall in all its illuminated splendor, last month’s Yosemite winter workshop had already been a success. Nevertheless, after dinner on our next to last night I took the group to this peaceful bend in the Merced River to photograph Half Dome beneath the stars.

I started with a high ISO test shot to get the exposure info for everyone, then converted to a long exposure that allowed me to ignore my camera for a half hour or so while I worked with the rest of the group. Helping with focus, composition, and exposure, I made sure everyone had had a success before suggesting we wrap up.

The fabulous photography is only part of what makes these night shoots memorable–they’re also just plain fun. That night we ended up staying out for about an hour, shooting, shivering, and laughing–lots of laughing. And as the group packed up, I returned to my camera and found this waiting for me.

Check out next year’s Yosemite winter workshop.

Clouds are Underrated

Posted on March 11, 2012

Blue skies and bright sunshine are great for tourists, but they can ruin a photographer’s day. Granted, warm sunrise and sunset light casts dramatic shadows and warms the landscape for a few quiet minutes at the beginning and end of the day. But when the sun is up, the light is harsh and tourists swarm like ants to a picnic.

On the other hand, an overcast sky diffuses sunlight, diminishes shadows, and softens the landscape. While diffuse overcast light isn’t usually as dramatic as warm early and late direct sunlight, it’s always wonderfully photographable. It also keeps the teeming masses at bay. If given a choice between dramatic sunrise and sunset light bookending a day of blues skies, or a full day of flat, overcast light, I’d take the overcast day without hesitation.

First Light, Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley: On most mornings, direct sunlight skims Mesquite Flat Dunes’ sandy undulations, etching straight lines and graceful curves that photographers crave.

Death Valley’s Mesquite Flat Dunes are gorgeous when the day’s first light peeks over the Funeral Mountains and skims the dunes’ pristine ridges and curves, casting extreme shadows that exaggerates everything wonderful about sand dunes. In an arid environment that rarely sees clouds, these dunes near Stovepipe Wells are a must-shoot for serious photographers.

But I’m afraid in their desire to duplicate the beautiful, high-contrast sunrise images that have preceded them, photographers overlook the possibilities when the sun doesn’t arrive. I love photographing sand dunes beneath cloudy skies, and can’t understand the disappointment I hear when dune photographers (who should know better) lament cloudy skies. I realize overcast doesn’t offer the kind of bold shadows that create the dramatic images everyone else has, but as someone who constantly looks to photograph things a little differently than others have (of course that doesn’t make me unique), I just love these dunes in more subdued light.

In last month’s Death Valley workshop, it was pretty obvious that we wouldn’t be seeing much sun at sunrise on the morning of our dune shoot. Nevertheless, as we prepared for the one mile trek in the pre-dawn darkness, I reassured everyone that they were in for a treat. (I couldn’t help but wonder if they thought I was selling them a bill of goods, but everyone seemed in good spirits as we followed our flashlights across the sand.)

I’d selected a relatively remote location that tends to offer a better chance of solitude and sand unmarred by footprints. Getting there is slightly more work, but nothing more than anyone in the group could handle. The slightly extra effort turned out to be worth it, as we found only a handful of footprints and saw no other photographers while we were out there.

While it was still fairly dark as we scaled the final dune and prepared to set up, flashlights were no longer necessary. Not only is shadowless twilight vastly underrated for photography, starting early gives everyone a chance to familiarize themselves with the scene before the sky starts to light up, so I encouraged everyone to start shooting as soon as they were ready.

As expected, the rising sun never made its way directly onto the dunes that morning, but it did find enough openings to paint the clouds in all directions with vivid reds and pinks, a rare treat in Death Valley (and an unexpected bonus). The image at the top of the page was captured about forty-five minutes after sunrise–without clouds, the best light would have been long passed by then. To emphasize the delicate, repeating ridges in the sand, I dropped my tripod as close to sand-level as it would go, stopping down to f16 and focusing maybe twenty feet in front of me to maximize depth of field. I used the diagonal “valley” in the middle distance to lead the eye through the scene, and because the sky wasn’t particularly interesting, relegated it to a thin strip above Death Valley Buttes and the Funeral Mountains.

All in all, a nice morning, and (I think) a good lesson for all.

Reflecting on reflections

Posted on March 4, 2012

Winter Reflection, El Capitan, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

1.3 seconds

F/16.0

ISO 100

19 mm

What is it about reflections? I don’t know about you, but I absolutely love them–I love photographing them, and I love just watching them. Like a good metaphor in writing, a reflection is an indirect representation that can be more powerful than its literal counterpart. In that regard, part of a reflection’s tug is its ability to engage the brain in different ways than we’re accustomed: Rather than processing the scene directly, we first must mentally reassemble the reverse world of a reflection, and in the process perhaps see the scene a little differently.

Because a camera renders our dynamic world in a static medium, water’s universal familiarity makes it a powerful tool for photographers. We blur or freeze in space a plummeting waterfall to convey a sense of motion that conjures auditory memories of moving water. Conversely, the mere image of a mountain reflecting in a lake can convey stillness and engender the peace and tranquility of standing on the lakeshore.

This El Capitan winter reflection is another from last month’s Yosemite winter workshop. Arriving at Tunnel View before sunrise, we found a world covered in snow and smothered by clouds. But as daylight rose, the clouds parted and we were treated to a classic Yosemite Valley clearing storm scene. The photography was still great when I herded everyone away from Tunnel View so we’d have time to capture as much ephemeral grandeur as possible in the limited time before the snow disappeared. I tell my groups that, while the photography is still great where we are, it’s great elsewhere too. This approach ensure that not only does everyone get beautiful images, they get a variety of beautiful images.

El Capitan Bridge was our second stop after Tunnel View. El Capitan is so large and close here that capturing it and its reflection in a single frame is impossible without a fisheye lens, or stitching multiple images. But sometimes the desire to capture everything the eye sees introduces distractions. Feeling a bit rushed, I inhaled and forced myself to slow down and simply absorbed moment, soon realizing that it was the reflection that moved me most.

I attached my 17-40 and tried fairly wide vertical and horizontal compositions that highlighted the best parts of the scene, twisting my polarizer in search of an orientation that captured the the reflection while still revealing the interesting world beneath the surface. Of the dozen or so frames that resulted, this may be my favorite for the way it conveys everything in those few sunlit, snowy minutes when the world seemed silent and pure.

* * * *

A note to you skeptics: I’m asked from time-to-time why the trees are white, while their reflection is green. This actually makes perfect sense once you realize that you’re looking at the top of the snow-covered branches, while the reflection is of the underside of the branches, which are not covered with snow.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A gallery of reflections

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.