If at first you don’t succeed…

Posted on November 7, 2014

Floating Leaves, Merced River, Yosemite

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

105 mm

.6 seconds

F/11

ISO 800

In early November of 2007 I took a picture that didn’t quite work out. That’s not so unusual, but somehow this one stuck with me, and I’ve spent seven years trying to recreate the moment I missed that night.

On that evening seven years ago, the sun was down and the scene I’d been working for nearly an hour, autumn leaves clinging to a log in the Merced River, was receding into the gathering gloom. The river darkened more rapidly than the leaves, and soon, with my polarizer turned to remove reflections from the river, the leaves appeared to be suspended in a black void.

I’d decided my scene lacked a visual anchor, a place for the eye to land, so I waited (and waited) for a leaf to drift into the top of my framed. On my LCD the result looked perfect, and I felt rewarded for my persistence. But back home on my large monitor, I could see that everything in the frame was sharp except my anchor point. If only I’d have bumped my ISO instead of my shutter speed….

Intrigued by the unrealized potential, I returned to this spot each autumn, but the stars never aligned—too much water (motion); dead (brown) leaves; no leaves; too many leaves; no anchor point—until this week. Not only did I find the drought-starved Merced utterly still, “my” log was perfectly adorned with a colorful leaf assortment anchored by an interlocked pair of heart-shaped cottonwood leaves.

I worked the scene until the darkness forced too much compromise with my exposure settings. In the meantime, I filled my card with horizontal and vertical, wide and tight, versions of the scene with the log both straight and diagonal. I also played with the polarizer, sometimes dialing up the reflection of overhanging trees. But I ultimately decided on the one you see her, which is pretty close to my original vision.

I can’t begin to express how happy photographing these quiet scenes makes me. I’ve done this long enough to know that it’s the dramatic landscapes and colorful sunsets that garner the most print sales and Facebook “Likes,” but nothing gives me more personal satisfaction than capturing these intimate interpretations of nature.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Autumn Intimates

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Plan B

Posted on October 30, 2014

I usually approach a scene with a plan, a preconceived idea of what I want to capture and how I want to do it. But some of my favorite images are “Plan B” shots that materialized when my original plan went awry due to weather, unexpected conditions (or my own stupidity).

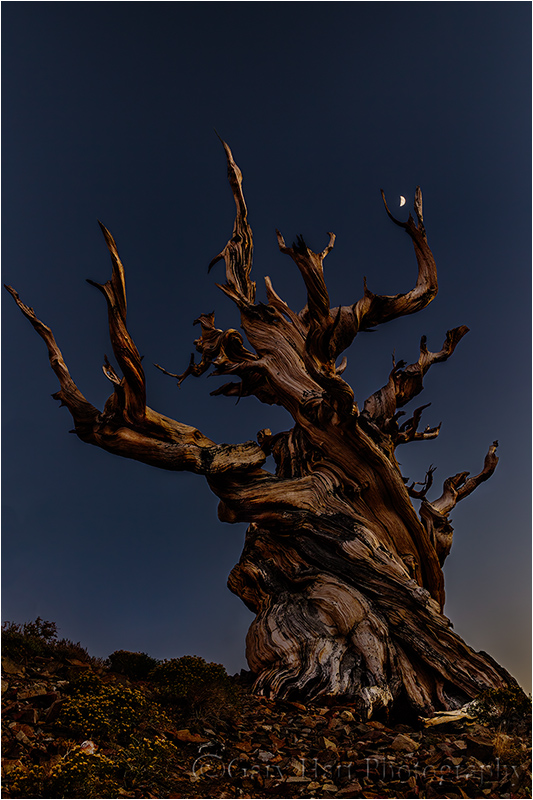

In my recent Eastern Sierra workshop, the clouds I always hope for never materialized. Whenever this happens I try to use the clear skies for additional night photography, but I’ve always been a little reluctant to keep my groups out late in the bristlecones because: 1) it’s colder than many are prepared for (late September or early October and above 10,000 feet); 2) it’s an hour drive back to the hotel the night before a very early sunrise departure. But this year, after spelling out the negatives, I gave my group the option of staying out to shoot the bristlecones beneath the stars. My plan was to arrange for a car (or two) to take back those who didn’t want to stay, but it turned out everyone was all-in.

In most of my trips I know exactly where the moon will be and when, but for this trip I hadn’t done my usual plotting—I knew it would be a 40 percent crescent dropping toward the western horizon after sunset, but hadn’t really factored the moon into my plans. But as we waited for the stars to come out, I watched moon begin to stand out against the darkening twilight and saw an opportunity I hadn’t counted on.

Moving back as far as I could to maximize my focal length (so the moon would be as large as possible in my frame) required scrambling on a fairly steep slope of extremely loose, sharp rock (while a false step wouldn’t have sent me plummeting to my death, it would certainly have sent me plummeting to my extreme discomfort). Next I moved laterally to align the moon with the tree, and dropped as low as possible to ensure that the tree would stand out entirely against the sky (rather than blending into the distant mountains). Wanting sharpness from the foreground rocks all the way to the moon, I dialed my aperture to f/16 and focused on the tree (the absolute most important thing to be sharp).

With the dynamic range separating the daylight-bright moon and the tree’s deep shadows was almost too much for my camera to handle, I gave the scene enough light to just slightly overexpose the moon, making the shadows as bright possible. Once I got the raw file on my computer at home, in Lightroom/Photoshop I pulled back the highlights enough to restore detail in the moon, and bumped the shadows slightly to pull out a little more detail there.

As you can see, even at 40mm, the moon is a tiny white dot in a much larger scene. But I’ve always felt that the moon’s emotional tug gives it much more visual weight than its size would imply. Without the moon this would be an nice but ordinary bristlecone image—for me, adding the moon sweetens the result significantly.

A Plan B gallery (images that weren’t my original goal)

Click an image for a lager view, and to enjoy the slide show

Seven reasons photographers love rain

Posted on October 22, 2014

Hidden Leaf, Mt. Hood, Oregon

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

168 mm (plus 48mm of extension)

1/100 second

F/4

ISO 400

The difference between a photographer and a tourist is easily distinguished by his or her response to rain: When the rain starts, the photographer grabs a camera and bolts outside, while the tourist packs up and races for shelter.

Seven reasons photographers love rain

- Smooth, (virtually) shadowless light that eliminates the extreme contrast cameras struggle to handle, and enhances color saturation

- Clouds are vastly more interesting than blue skies

- The best stuff happens in the rain: rainbows, lightning, clinging water droplets

- Clean air means more vivid sunrises and sunsets

- Replenished lakes, rivers, streams, and waterfalls for days, weeks, or months of great photography (rain or not)

- Low light makes easier the long shutter speeds necessary for soft water effects

- (Last, but not least,) we have the landscape to ourselves

Case in point

This week Don Smith and I traveled to Hood River, Oregon for some autumn photography, and to do more prep and reconnaissance for next spring’s Columbia River Gorge photo workshops. It’s rained every day we’ve been here, and you won’t find two happier (albeit wetter) photographers. Not just because our California bones miss rain (they do), but because there is no better time to take pictures than a rainy day.

Monday morning Don and I drove to Lost Lake to scout it as a potential workshop location. Climbing from near sea level to over 3,000 feet in a steady rain, we passed through deciduous forests in varying stages of green, yellow, orange, and red. The fall color peaked at around 2,000 feet, dwindled as we climbed further, until by the time we reached the lake, most of the colorful leaves were on the ground or whisked away by mountain breezes. While Mt. Hood was completely obscured by rainclouds, we spent a couple of hours exploring near the lake before heading back down the mountain with no specific plan other than to stop somewhere and photograph the color we’d enjoyed on the drive up.

Partway down the mountain we pulled over beside an evergreen forest liberally mixed with yellow and red maples, donned our rain gear, and went to work. With dense, low clouds shrinking the view to just the immediate vicinity, grand panorama were out of the question and my 70-200 became my weapon of choice for its ability to isolate nearby leaves and limit depth of field.

An essential but frequently overlooked component of successful rainy day photograph is a (properly oriented!) polarizer to mitigate the ubiquitous, color-sapping sheen reflecting back from every exposed surface. This is a no-exception thing for me—I don’t care if it’s already dark and the polarizer robs me of two more stops of light, without it, images from wet scenes like this would be a complete failure. In this case I bumped my ISO to 400 (and would have as high as necessary if there had been more wind) before composing a single frame.

Beautiful as it was, a scene like this starts as a hodgepodge of disorganized color. Fortunately, it’s never long before individual elements start manifesting—the longer I stay, the more (and smaller) detail I see, until even the littlest thing stands out and I can’t believe it had been there all along. Knowing all this, I usually start at my lens’s wider range and gradually work tighter as the surroundings become more familiar.

And so it was with this little leaf, tucked into the forest behind several layers of dense and dripping branches, hiding from my gaze until nearly an hour into my visit. From the forest’s outskirts I zoomed to 200mm and composed a few frames through the tangle of branches, but it wasn’t long before I needed to be closer.

When I spy something interesting, it’s easy to crash through the forest like an angry grizzly (or frightened bison), but because I was extremely concerned about dislodging the fragile raindrops, I found myself deliberately stalking my prey, more like a stealthy cougar. (I could have just as easily compared my advance to a slithering snake, but for some reason this cougar analog resonated with me. Go figure.) When I made it so close that I was inside my lens’s focus range, I added an extension tube, and finally a second tube.

By this time I was just a few inches from the leaf, and while this ultra-close view was pretty cool, I felt my frame needed more that just a pretty leaf. Until this point I’d been pushing the nearby branches and leaves aside, out my view. But realizing that I was so close (the leaf closest brushed my lens), and my range of focus was so thin, that they would blur to a smear of red that cradled my subject.

With a paper-thin depth of field, finding the right focus point is essential. I also knew that I wouldn’t be able to get the entire leaf sharp, so I used live-view to focus on the center water drop (because that’s where I want my viewer’s eye to start).

Staying dry

The rain came and went for the duration of our stay, but never reached an intensity that made shooting difficult. In this case there wasn’t much wind, making my umbrella particularly useful for keeping raindrops off my lens. Nevertheless, without a little simple preparation, this image wouldn’t have been possible. I’ve learned never to take a photo trip without basic rain gear. For me that’s:

- A thin, waterproof shell that fits over whatever else I’m wearing (shirt, jacket, or whatever the temperature calls for)

- Waterproof pants that fit over my regular pants—I have an unlined pair for moderate temperatures, and a lined pair what I think it could get cold, and decide between when I pack

- Waterproof hiking boots

- Waterproof hat

- Wool or synthetic shirts, pants, and socks that will keep me comfortable when my rain gear causes me to perspire (no cotton!)

- Umbrella for my camera—because I’m dry (see above), I can dedicate the umbrella 100 percent to keeping raindrops off my lens

- Towel to dry things (especially my lens!) when they get wet—I often borrow one from my hotel, which isn’t a problem as long as I remember to return it

- Plastic garbage bag to drape over my camera when it’s on the tripod waiting for me to do something productive—if I forget a garbage bag, the hotel’s laundry or trash liner bags work fine

A rainy day gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

It’s all about relationships

Posted on October 18, 2014

Star Trails Above an Ancient Bristlecone, Schulman Grove, White Mountains

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

28 mm

31 minutes

F/5.6

ISO 100

Relationships

Think about how much our lives revolve around relationships: romance, family, friends, work, pets, and so on. It occurs to me that this human inclination toward relationships almost certainly influences the photographic choices we make, and the way our images touch others.

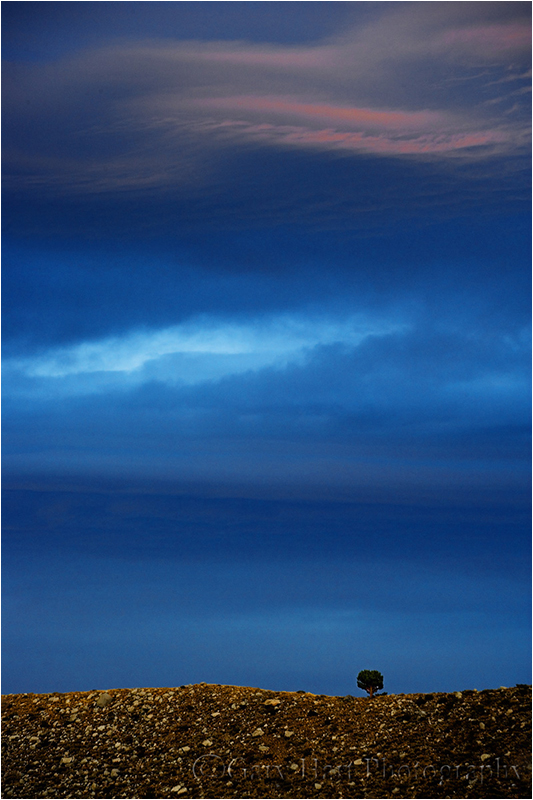

Whether it’s conscious or not, photographers convey relationships in their images. A pretty sunset is nice, but a pretty sunset over the Grand Canyon or Yosemite is especially nice. Likewise, why be satisfied with an image of a rushing mountain stream when we can accent the scene with an autumn leaf? And that tree up there on the hill? It sure would look great with a moon. These are relationships, two distinct subjects connected by a shared moment.

The more we can think in terms of relationships in nature, adding that extra element to our primary subject, or finding multiple elements and organizing them in a way that guides the eye through the frame, the more our images will reach people at the subconscious level that draws them closer and holds them longer.

On the other hand…

Some of my favorite images are of a solitary subject, and element in nature that stands alone in the scene—what’s up with that? I’ve decided (since this is my blog) that this the exception that proves the rule. As much as humans gravitate to relationships, what person doesn’t long for the peace of solitude from time to time? In the case the tree in the image below, it’s the absence of a relationship that draws us, or more accurately, it’s the tree’s relationship with an otherwise empty scene that appeals to the relationship overload we all experience from time to time.

Solitary Tree After Sunset, McGee Creek Canyon, Eastern Sierra

It’s the isolation of this small tree, its relationship with the void, that makes this image work for me.

Star Trails and Ancient Bristlecone: About this image

At 4,000+ years, the bristlecone pines of the White Mountains, east of Bishop, California, are among the oldest living things on Earth. They’re also among the most photogenic. Each year I take my Eastern Sierra photo workshop group to photograph the bristlecones of the Schulman Grove. Given the (rather gnarly) one hour drive would get us back to our hotel in Bishop quite late on the eve of a particularly early sunrise shoot, and night temperatures above 10,000 feet in late September are quite chilly, I’ve never kept the group out here for a night shoot. Until this year.

With clear skies and a 40 percent crescent moon, I couldn’t resist the opportunity to photograph these trees with just enough moonlight to reveal their weathered bark without washing out too many stars. Here was an opportunity to create the kind of relationship we all look for—juxtaposing these magnificent trees against an equally magnificent night sky. So after a nice sunset shoot, but before it became too dark, I had everyone find a composition they liked, lock it in on their tripod, and focus using the remaining light. When the stars started popping out, we began clicking—I started everyone the initial exposure settings, and helped them ensure that their images were sharp, but pretty soon most of them were managing quite fine without my help.

Our first frames were pinpoint stars, relatively short (30 seconds or less) exposures at wide-open apertures and very high ISOs. As the darkness became complete, we were equally thrilled number of stars and the amount of tree and rock detail the faint moonlight brought out in our images. Eventually most in the group wanted to recompose, which required re-focusing, no trivial task in the darkness. Normally an infinity focus on the moon will suffice at night, but the trees were so close, and our apertures so wide, that I felt it would be best to focus on a tree (to ensure its sharpness at the possible risk of slight softness in the stars). We found that by hitting the tree with an extremely bright light (or two), we could see just enough detail to manually focus. But just to be sure, I insisted that everyone verify their focus by scrutinizing a magnified image on their LCD.

When I was convinced that everyone had had success with pinpoint stars, I prepared them all for one final, long exposure star trail shot. Using the last pinpoint composition and focus (after verifying that it was indeed sharp), I did the math that would return the same exposure at 30 minutes that we’d been getting at 30 seconds—in this case, adding 6 stops of shutter speed meant subtracting 6 stops of ISO and aperture. When everyone was ready, we locked our shutters open in bulb mode, and then just kicked back and watched the sky.

My favorite part of these group shoots are these times when we can all just kick back together and appreciate the beauty of the moment, without the distraction of a camera. Overhead the Milky Way painted a faint white stripe through Cassiopeia, a couple of satellites danced faintly among the stars, and several meteors flashed. I didn’t even mind the occasional plane cutting the darkness (it didn’t hurt to know that Photoshop makes removing them quite simple now), and tried to guess its destination.

This shoot was certainly about finding the relationship between the these trees and the night sky they’ve basked beneath every night for thousands of years. But it was also about the stories and laughs we shared that night, cementing relationships between people who were strangers just a couple of days earlier—I know from experience some of these relationships will end with the workshop, but many will continue for years or even lifetimes.

A gallery of relationships in nature

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

A small dose of mind-bending perspective

Posted on October 12, 2014

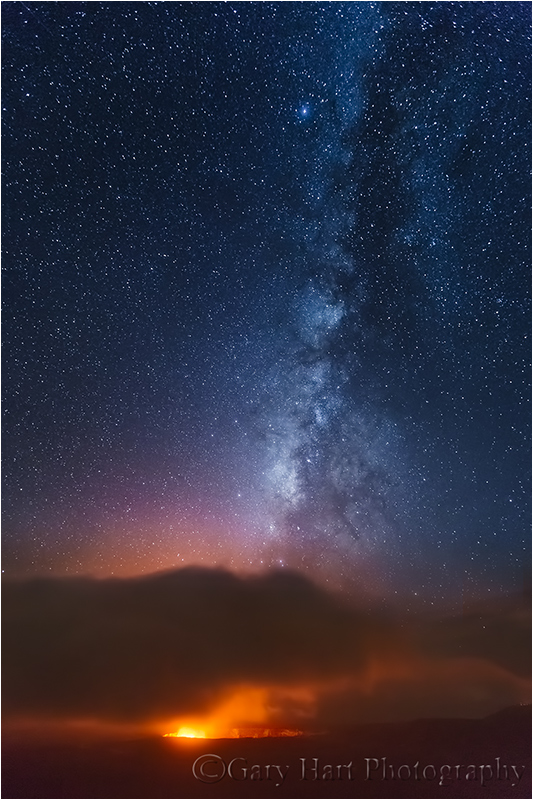

So what’s happening here? The orange glow at the bottom of this frame is light from 1,800° F lava bubbling in Halemaʻumaʻu Crater inside Hawaii’s Kilauea Caldera, reflecting off a low-hanging bank of clouds. The white band above the crater is light cast by billions of stars at the center our Milky Way galaxy. So dense and distant are the stars here, their individual points are lost to the surrounding glow. Partially obscuring the Milky Way’s glow are large swaths of interstellar dust, the leftovers of stellar explosions and the stuff of future stars. Completing the scene are stars in our own neighborhood of the Milky Way, stars close enough that we see them as discrete points of light that we imagine into mythical shapes—the constellations.

The Milky Way galaxy is home to every single star we see when we look up at night, and 300 billion more we can’t see—that’s nearly 50 stars for every man, woman, and child on Earth. Our Sun, the central cog in the solar system that includes Earth and the other planets wandering our night sky, is a minor player in a spiral arm near the outskirts of the Milky Way. But before you get too impressed with the size of the Milky Way, consider that it’s just one of 500 billion or so galaxies in the known Universe—that’s right, there are more galaxies in the Universe than stars in our galaxy.

Everything we see is the product of light—light created by the object itself (like the stars), or created elsewhere and reflected (like the planets). Light travels incredibly fast, fast enough that it can span even the two most distant points on Earth faster than humans can perceive, fast enough that we consider it instantaneous. But distances in space are so great that we don’t measure them in terrestrial units of distance like miles or kilometers. Instead, we measure interstellar distance by the time it takes for a beam of light to travel between two objects—one light-year is the distance light travels in one year.

The ramifications of cosmic distance are mind-bending. Imagine an Earth-like planet revolving the star closest to our solar system, about four light-years away. If we had a telescope with enough resolving power to see all the way down to the planet’s surface, we’d be watching that planet’s activity from four years ago. Likewise, if someone on that planet today (in 2014) were watching us, they’d see Lindsey Vonn claiming the gold in the Women’s Downhill at the Vancouver Winter Olympics, and maybe learn about the unfolding WikiLeaks scandal.

In this image, the caldera’s proximity makes it about as “right now” as anything in our Universe can be—the caldera and I are sharing the same instant in time. On the other hand, the light from the stars above the caldera is tens, hundreds, or thousands of years old—it’s new to me, but to the stars it’s old history. Not only that, every point of starlight here is a version of that star created in a different instant in time. It’s possible for the actual distance separating two stars to be so great, that we see light from the younger star that’s older than the light from the older star.

So what’s the point of all this mind bending? Perspective. It’s easy (essential?) for humans to overlook our place in this larger Universe as we negotiate the family, friends, work, play, eat, and sleep that defines our very own personal universes. I doubt we could cope otherwise. But when I start taking my life too seriously, it helps to appreciate my place in the larger Universe. Nothing does that better for me than quality time with the night sky.

About this image

My 2014 Hawaii Big Island photo workshop group made three trips to photograph the Kilauea Caldera beneath the Milky Way. On the first night we got a lot of clouds, with a handful of stars above, and just a little bit of Milky Way. Nice, but not the full Milky Way everyone hoped for. So I brought everyone back a couple nights later—this time we got about ten minutes of quality Milky Way photography before the clouds closed in. The following night we gave the caldera one more shot and were completely shut out by clouds. Such is the nature of night photography in general, and on Hawaii in particular. This image is from our second visit.

My concern that night was making sure everyone was successful, ASAP. I started with a test exposure to determine the exposure settings that would work best for that night (not only does each night’s ambient light vary with the volcanic haze, cloud cover, and airborne moisture, the caldera’s brightness varies daily too). Once I got the exposure down and called it out to the group, most of my time was spent helping people find and check their focus, and refine their compositions (“More sky! More sky!”). Bouncing around in the dark, I’d occasionally stop at my camera long enough to fire a frame, never staying long enough to see the image pop up on the LCD. I ended up with a half dozen or so frames, including this one from early in the shoot.

Join me on the Big Island next year

Learn more about starlight photography

A starlight gallery

Click an image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide show

A simple how and when of fall color

Posted on October 6, 2014

Few things get a photographer’s heart racing more than the vivid yellows, oranges, and reds of autumn. And the excitement isn’t limited to photographers—to appreciate that reality, just try navigating New England backroads on a Sunday afternoon in October.

Innkeeper logic

But despite all the attention, the annual autumn extravaganza is fraught mystery and misconception. Showing up at at the spot that guy in your camera club told you was peaking at this time last year, you might find the very same trees displaying lime green mixed with just hints of yellow and orange, and hear the old guy behind the counter at the inn shake his head and tell you, “It hasn’t gotten cold enough yet—the color’s late this year.” Then, the next year, when you check into the same inn on the same weekend, you find just a handful of leaves clinging to exposed branches—this time as the old guy hands you the key he utters, “That freeze a few weeks ago got the color started early this year—you should have been here last week.”

While these explanations may sound reasonable, they’re not quite accurate. Because the why and when of fall color is complicated, observers resort to memory, anecdote, and lore to fill knowledge voids with partial truth and downright myth. Fortunately, science has given us a pretty good understanding of the fall color process.

It’s all about the sunlight

The leaves of deciduous trees contain a mix of green, yellow, and orange pigments. During the spring and summer growing season, the green chlorophyl pigment overpowers the orange and yellow pigments and the tree stays green. Even though this chlorophyl is quickly broken down by sunlight, the process of photosynthesis that sustains the tree, during the long days of summer it is continuously replaced.

As the days shrink toward autumn, things begin to change. Cells at the abscission layer at the base of the leaves’ stem (the knot where the leaf connects to the branch) begin the process that will eventually lead to the leaf dropping from the tree: thickening of cells in the abscission layer blocks the transfer of carbohydrates from the leaves to the branches and the movement of minerals to the leaves that had kept the tree thriving all summer. Without these minerals, the leaves’ production of chlorophyl dwindles and finally stops, leaving just the yellow and orange pigments. Voila—color!

Sunlight and weather

Contrary to popular belief, the timing of the onset of this fall color chain reaction is much more daylight-dependent than temperature- and weather-dependent—triggered by a genetically programmed day/night-duration threshold, and contrary to innkeeper-logic, the trees in any given region will commence their transition from green to color at about the same time each year (when the day length drops to a certain point).

Nevertheless, though it doesn’t trigger the process, weather does play a significant part in the intensity, duration, and demise of the color season. Because sunlight breaks down the green chlorophyl, cloudy days after the suspension of chlorophyl creation will slow the coloring process. And while the yellow and orange pigments are present and pretty much just hanging out, waiting all summer for the chlorophyl to relinquish control of the tree’s color, the red and purple pigments are manufactured from sugar stored in the leaves—the more sugar, the more vivid the red. Ample moisture, warm days, and cool (but not freezing) nights after the chlorophyl replacement has stopped are most conducive to the creation and retention of the sugars that form the red and purple pigments.

On the other hand, freezing temperatures destroy the color pigments, bringing a premature end to the color display. Drought can stress trees so much that they drop their leaves before the color has a chance to manifest. And wind and rain can wreak havoc with the fall display—go to bed one night beneath a canopy of red and gold, wake the next morning to find the trees bare and the ground blanketed with color. And of course all these weather factors come in an infinite number of variations, which makes each year’s color timing and intensity a little different from the last.

Despite our understanding of the fall color process, Mother Nature still holds some secrets pretty close to her vest—just when we think we’ve got it all figured out, she’ll surprise us. For example, last year’s Eastern Sierra fall color featured lots of black leaves that I attributed to California’s extreme drought conditions. With the drought persisting, and in fact intensifying, this year, I feared this fall would be even worse. So I was quite pleased to find everything going along right on schedule, with lots of yellow, more red than usual, and hardly a black leaf to be seen. Go figure.

About this image

My first visit to Zion National Park, three years ago, found the fall color peaking. I’d love to say this was through expert knowledge and careful planning, but it just happened that I’d been helping Don Smith with a workshop in Moab and we’d tacked on an extra day to play in Zion. We arrived early enough in the afternoon to explore and shoot for several hours before sunset, and were so thrilled by what we’d found that we decided to return for an hour the or so the next morning before heading home.

Though my time was limited, a couple of things made this morning’s shoot even more productive than previous afternoon’s. First was the familiarity I’d gained the day before. And second was the morning’s soft light and utter stillness. Anxious to get going, we started before sunrise and were the first people to enter the canyon that morning—without wind or human interference, the air was so still that it seemed even the river was whispering. In these conditions it’s easy to forget time, ignore the chill, and immerse myself in world devoid of human obligation and discomfort.

What struck me most about Zion’s color was the crimson maples, a color we just don’t get in California. While yellow was ubiquitous, red leaves were quite plentiful too, and I tuned my vision to identify any red I could highlight against the predominant yellow. Identifying this bunch of red leaves was just the beginning of my composition. Isolating a subject requires more than positioning it in the frame’s two-diminsional up-down/left-right planes; it also requires controlling the virtual third dimension, depth, by careful management of the background and depth-of-field. In this case I refined my find by moving left/right and up/down until I was satisfied with the way the background complemented the red leaves.

Equally important was finding the appropriate depth of field—too little DOF would mean not enough of the nearby red leaves, my subject, would be sharp; too much DOF much would risk resolving so much background that it would compete with my leaves. I decided to use my 70-200 lens, moving back far enough to include all of the red leaves at 200mm. That long focal length compressed the distance separating the foreground leaves and background trees (make the yellow trees seem closer to the red leaves). Because depth of field decreases with focal length, even at f16 background trees were soft enough.

A few other subtle but significant considerations went into this image. First, note the long shutter speed: the air was so still that I had no qualms about using ISO 200, f16, and a polarizer, even though it dropped my shutter speed to four seconds. Also, don’t underestimate the importance of a polarizer in shady or overcast scenes: color-robbing glare from leaves’ waxy sheen is reduced significantly by a properly oriented polarizer. And finally, in front of these leaves were a few fluffy white seed pods—I knew they were close enough that at 200mm they would be blurred to little puffs of white, and simply decided to shoot through them.

Read how to photograph fall color in my Fall Color Photo Tips article.

A fall color gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

If it’s Tuesday, this must be Bishop

Posted on September 30, 2014

Bristlecone Moonrise, Patriarch Grove, White Mountains, California

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

60 mm

.3 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

I have no one to blame but myself (a significant downside of being self-employed), and know I’m not going to get a lot of sympathy, but I just need to share how crazy my last few weeks have been. I’m in the final third of a stretch of three photo workshops in three time zones in three weeks, separated by a grand total of 20 hours at home.

Today I’m in Bishop, California, for day-two of my Eastern Sierra workshop that started yesterday in Lone Pine (California) and wraps up Friday morning in Lee Vining (California). This marathon travel schedule kicked-off on Thursday, September 12, when I left Sacramento for my Hawaii Big Island workshop. I finished that workshop with a Kilauea night shoot on Friday the 19th; Saturday morning I was back to the Hilo airport for my flight home (plane change and layover in Honolulu), finally dragging in the front door about 11 p.m. Saturday night.

At 8:00 a.m. Sunday morning my daughter deposited me back at the Sacramento airport for a flight to Salt Lake City, where I met Don Smith for the five-hour drive to Jackson Hole to help Don with his Grand Tetons workshop. Because the Hawaii/Wyoming weather conditions are so different, and my turnaround was so quick, I actually packed for the Teton before leaving for Hawaii (I’m so glad I did).

After a week in the Tetons, we wrapped up that workshop with a wet sunrise shoot on Saturday morning—then it was straight to the Jackson airport for a series of flights and airport shuttle that got me home Saturday night. I had just enough time to upload my images, refresh my suitcase, catch five hours sleep, and pack the car before heading back out the door early Sunday morning for the six-hour drive to Lone Pine for my Eastern Sierra workshop.

Am I tired? Probably, but I won’t feel it until my drive home on Friday. Am I complaining? Absolutely not. Not only did I do this to myself, how could anyone complain about three weeks filled with Hawaii, the Grand Tetons, and the Eastern Sierra?

And honestly, you can’t really be happy doing what I do without at least being able to tolerate travel. This year, before my current marathon travel stretch, I’ve been to Death Valley, Yosemite (many times), Maui, Kauai, the Grand Canyon three times (including a raft trip), plus Page and Sedona. And truth be told, I enjoy driving, and don’t mind flying. Driving relaxes me, and flying is an opportunity to catch up on my reading and writing. Nevertheless, it will be nice to have consecutive days home, in my own bed,with the alarm off—before next month’s trip to the Columbia River Gorge….

A little more about the Eastern Sierra and this image

Everyone knows about Hawaii, and most know about the Grand Tetons, but mention of the Eastern Sierra still elicits a blank stare from many people. That’s probably because most tourists haven’t discovered it yet (the photographers certainly have). With Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills (if you’ve ever seen a John Wayne, Gary Cooper, or John Ford western, you know the Alabama Hills), the bristlecone pines (in the White Mountains, across the Owens Valley from the Eastern Sierra), Mono Lake, Yosemite’s Tuolumne Meadows, and lots of fall color, it’s my most diverse photo workshop.

We started yesterday evening with a nice shoot of the Whitney Portal waterfall, in the shadow of Mt. Whitney. This morning we photographed alpenglow on Mt. Whitney and the Sierra crest from Whitney Arch (aka, Mobius Arch) in the Alabama Hills. After breakfast we made the easy, scenic one hour drive to Bishop, which is where I am now (thank you, Starbucks). Tonight it’ll be the bristlecone pines, at more than 4,000 years, among the oldest living things on Earth (older even than Larry King!).

For tonight’s bristlecone shoot I’ll take the workshop to the relatively accessible Schulman Grove. But when I’m on my own, I often continue thirteen unpaved miles to the Patriarch Grove. And that’s the trip I made a few years ago, because I thought the bristlecones would make a nice foreground for the rising full moon, and because the Patriarch Grove has a clearer view of the eastern horizon than the Schulman Grove.

At the Patriarch Grove, finding the clear view I wanted required me to take off cross-country. Unfortunately, when I scaled the final ridge, I found the horizon obscured by clouds. Not to worry, the light was perfect for photographing these weather-worn, gnarled trees. I’m usually pretty good about catching the moon’s appearance, but because I’d written it off for this evening (shame on me), I failed to register that the clouds were breaking up. Which is why I was both surprised and pleased to find the moon’s glowing disk hovering just above the clouds a few minutes after sunset.

I’d been wandering so much, and so focused on the nearby scene, that I hadn’t identified a particular tree for any potential moon shot (also shame on me). With very little time before the foreground/moon contrast became un-photographable, I felt quite fortunate to find this tree so quickly. A wide composition would have shrunk the moon to nearly invisible, so I stepped back as far as the terrain allowed so I could zoom closer and compress the separation (and enlarge the moon a little). With a vertical composition, I had to decide on rocks or sky, but it wasn’t hard to decide that foreground rocks were far more interesting than empty sky.

Let’s see, what’s tomorrow? Wednesday. Lee Vining, here I come….

An Eastern Sierra gallery

Click an image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide show

Let’s all take a breath and step away from the ledge

Posted on September 26, 2014

Tree at Sunset, McGee Creek Canyon, Eastern Sierra

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

1/40 second

F/7.1

ISO 400

126 mm

National Forest Service commercial photography policy (it’s not as bad as you think)

I’ve received a number of inquiries (some quite panicked) in the last few days asking my opinion about the “new” National Forest Service policy regarding commercial photography. I’ve actually read some media accounts that imply that simply whipping out your iPhone and snapping a mountain lake risks a $1,000 fine. After doing a little research, I’ve confirmed that this is yet one more example of the media whipping the public into a frenzy by selecting a few facts and presenting them in the most sensational way. Here’s an example: http://www.esquire.com/blogs/news/1000-dollar-fine-for-pictures-in-the-forest.

Not being an expert on the subject, I can’t really say whether there are any factual errors in that article. But I can say that it’s a pretty self-serving (he’s certainly received a lot of attention) distortion of the actual policy I found posted on the National Forest Service website (http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5355613.pdf). Here’s the excerpt from the NFS document that applies to me and my photography:

“Still Photography: A special use permit is required for activities on National Forest System lands when the purpose is to: (1) Promote or advertise a product or service using actors, models, sets, or props that are not part of the site’s natural or cultural resources or administrative facilities; or (2) Create an image for commercial sale by using sets or props. In addition, a permit may be required if no activities involving actors, models, sets, or props are proposed when: (1) The activity takes place in an area where the general public is not allowed; or (2) In situations in which the Forest Service would incur additional administrative costs to either permit or monitor the activity.“

As far as I’m concerned, this policy doesn’t sound unreasonable, nor does it sound like my livelihood is in imminent peril, and I’m pretty sure no one’s photographic life is jeopardized.

As someone who conducts 10-12 photo workshops each year, I’m a strong advocate for reasonable rules and restrictions that protect the natural resources that are the foundation of my business (and my mental health). I have no problem jumping through all the necessary hoops—liability insurance, first aid certification, group size, and so on—and paying the annual fees (usually in the $200-$250 range) that each workshop location’s permit process requires. I also find the people I deal with at these locations to generally be quite helpful, reasonable to deal with, not to mention downright flexible when a unique situation arise (like the time I overlooked an application deadline and didn’t discover my error until the last minute).

It’s interesting that this issue should arise right now, as I’m in Grand Tetons National Park helping Don Smith with his photo workshop here. The talk around town is about a moose that had to be put down a couple of days ago when she broke her leg after being spooked by a horde of overzealous wildlife photographers. It’s a rare trip that I don’t witness photographers do illegal or foolish things that imperil themselves (not to mention the lives of those who would need to rescue them), frighten or threaten wildlife, and damage the fragile ecosystem. It’s this very small minority of selfish and/or ignorant photographers who put all photographers in a bad light, leaving National Park and Forest authorities no choice but to implement tighter regulation. I’ve spoken up and intervened at times, but I often regret the times that I just shook my head and walked away after witnessing something I knew to be wrong.

So. Would I support the kind of heavy-handed National Forest Service regulations that the media implies is coming our way? Absolutely not. And while I don’t think something like that is imminent, I do wish photographers would do a better job of policing themselves, both by managing their own behavior, and by respectfully speaking up when another photographer behaves irresponsibly before we’re all affected by more restrictive policy and stricter enforcement.

About this image

What better way to demonstrate my lack of concern by posting this image from Inyo National forest. This tree on the dirt road to McGee Creek had been on my radar for several years, but I’d never found the conditions suitable to photograph it. But following an afternoon fall color shoot at the creek, the vestiges of sunset lit these tilde-shaped clouds. I knew exactly where I wanted to be but wasn’t sure I had time to get there. I raced down the road, pulled my truck to the side, and had time for just a couple of frames before the color faded.

A National Forest Gallery

Addition by subtraction

Posted on September 22, 2014

In my previous blog post I mentioned that I lost a couple of my Hawaii locations to Hurricane Iselle. Not only was the loss no big deal, it proved a catalyst that jarred me from my rut and into more exploring.

This location was at first glance an exposed, twenty foot cliff above the Pacific with a great view up the Puna Coast, past palm trees and surf-battered, recently cooled lava. But, as with most spots, there’s a lot more if you take the time to look. Exploring the dense growth lining the coast here soon brought me to views of tiered, reflective pools. While getting these views required a little bushwhacking followed by some creative rock-hopping, I know if I were by myself, that’s where I’d have ended up. But when leading a group I need to be more careful—it’s one thing when I injure myself doing something stupid, and something entirely different to guide others into risky spots.

Each group is different when it comes to risk taking—in this case when I offered to guide the group toward the pools I’d found the previous day, only two followed, so I returned to the rock platform where everyone seemed quite content with the spectacular view—the rocks and pools will wait for another visit. And while everyone may have missed a few photo opportunities on the safety of our cliff, not only did we still get some great stuff, we were in close enough proximity that laughter abounded (all without missing a click, of course).

About twenty feet below us, large waves sent explosions of spray skyward; occasionally a perfect coincidence of wave and wind dusted the group with a fine mist that was more refreshing than soaking. Our view here was northeast, which meant the setting sun was more or less behind us. By this, our final sunset, everyone had started to understand why I say my favorite sunrise/sunset view is usually away from the sun. Not only is the light easier to manage in that direction, the Earth-shadow paints the post-sunset (or pre-sunrise) horizon with rich pink and blue hues that the camera can reveal long after they’ve faded to the eye.

The best views were straight up the coast, so I quickly decided a vertical composition was the way to go here. I experimented with different shutter speeds to vary the blur in the waves, but as the scene darkened, each blur became some variation of extreme motion blur. The other major variable in the scene was how wide to compose. With a large tree overhanging the rocks toward the back of the scene, including lots of foliage proved better than truncating everything but the protruding crown of that one tree.

I captured this frame about five minutes after sunset. Giving the scene enough light to bring out detail in the shaded, dark-green foliage without washing out the color in the sky, I employed a two-stop hard-transition Singh-Ray graduated neutral density filter. Instead of the standard GND horizontal orientation, I turned it vertically, aligning the transition with the coastline. To mask the transition, I vibrated the filter slightly left/right throughout the entire eight-second exposure. Smoothing the tones in Lightroom/Photoshop became quite simple, thanks to the GND at capture.

My periodic rounds during our shoot seemed to indicate that everyone was happy—this in spite of a couple of extreme drenchings at the hands of two large waves that far exceeded all that had preceded it to land squarely atop those on the southeast corner of our perch—but it wasn’t until someone exclaimed at the end of the shoot, “This is the best spot yet!” that I knew I’d found a keeper. My former (“lost”) locations were nice, but it was good to be nudged into remembering that unknown opportunities are usually just a little exploration away.

Upcoming Hawaii workshops

Maui Tropical Paradise (two nights in West Maui, two nights in Hana), March 2-6, 2015

Hawaii Big Island Volcanos and Waterfalls, September 14-18, 2015

A Hidden Hawaii Coast Gallery

Click an image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide show

One eye on the ocean, the other on the volcano

Posted on September 16, 2014

September 16, 2014

It’s easy to envy residents of Hawaii’s Big Island—they enjoy some of the cleanest air and darkest skies on Earth, their soothing ocean breezes ensure that the always warm daytime highs remain quite comfortable, and the bathtub-warm Pacific keeps overnight lows from straying far from the 70-degree mark. Scenery here is a postcard-perfect mix of symmetrical volcanoes, lush rain forests, swaying palms, and lapping surf. I mean, with all this perfection, what could possibly go wrong?

Well, let me tell you….

Last month Tropical Storm Iselle, just a few hours removed from hurricane status, slammed Hawaii’s Puna Coast with tree-snapping winds and frog-drowning rain that cut electricity, flooded roads, and disrupted many lives for weeks. Touring the area in and around Hilo, it’s easy to appreciate Hawaiian resilience—thanks to quick action, hard work, and continuous smiles, most visitors would find it difficult to believe what happened here just a month ago. But on the drive south of Hilo along the Puna Coast, I witnessed firsthand Iselle’s power in its aftermath. There beaches have been rearranged beyond recognition and entire forests have been leveled.

But despite its impact, Iselle is already old news. This month residents of Hawaii’s Puna region have done a 180, turning their always vigilant eyes away from the ocean and toward the volcano. In late June Kilauea’s Pu`u `O`o Crater dispatched a river of lava down the volcano’s southeast flank. Since Pu`u `O`o has been erupting continuously since 1983, this latest incursion didn’t initially raise many eyebrows. But the flow has persisted, advancing now at about 250 yards per day. While this isn’t “Run-for-your life!” speed, it’s more like high stakes water torture because there’s very little that can be done to stop, slow, or even deflect the lava’s inexorable march. Residents of the communities of Kaohe and Pahoa can do nothing but watch, pray, and prepare—if the volcano persists, they’re wiped out. Not only that, the lava flow also threatens the Pahoa Highway, currently the only route in and out for the thousands of residents of the Puna region.

Recent reports of increased activity on Muana Loa have also notched up the anxiety. Lava from its last eruption, in 1984, threatened Hawaii’s capital, Hilo, before petering out with just a few miles to spare. Because Muana Loa eruptions tend to be larger and more explosive than Kilauea eruptions, any increased activity there is taken very seriously.

Had enough? Well, there’s more thing: With its funnel-shaped bay and bullseye placement in the Pacific Ring of Fire, Hilo is generally considered the most tsunami vulnerable city in the world. Fatal tsunamis have struck the Big Island in 1837, 1868, 1877, 1923, 1946, 1960, and 1975. Yesterday my photo workshop group photographed sunrise at Laupahoehoe Point, where damage from the most deadly tsunami to strike American soil is still visible. That tsunami, in 1946 (before Hawaii became a state), traveled 2,500 miles from the Aleutian Islands to kill 159 Hawaiians, including 20 schoolchildren and 4 teachers in Laupahoehoe.

Despite this shopping list of threats and hardship, I don’t get the sense the Hawaiians want sympathy. Despite the unknown but potentially devastating consequences facing them, both imminent and potential, no one here is feeling sorry for themselves. There’s much talk about the current lava flow that will directly or indirectly impact every resident of the Big Island’s Hilo side, but no hand-wringing—life goes on and smiles abound. Indeed, everyone here seems to have sprung into action in one way or another, shoring up old long abandoned roads (the jungle claims anything left unattended with frightening speed), helping people move possessions to safe ground, offering temporary shelter, and whatever else might help.

The Aloha spirit is alive and well, and I have no doubt that it will persevere in the face of whatever adversity Nature throws at them.

About this image

My Hawaii photo workshop began Monday afternoon, but my brother and I arrived on the Big Island on Friday because I hate doing any workshop without first running all my locations to make sure there are no surprises. And this time it turned out to be a wise move—not only did I get a couple of extra days in paradise, I did indeed encounter surprises, courtesy of Iselle, when I discovered two of my go-to locations rendered inaccessible by storm damage. I spent Saturday searching for alternatives and by Saturday’s end had a couple of great substitute spots. That night we celebrated with a night shoot on Kilauea. (I was going to visit Kilauea anyway, but if I’d still been stressing about my locations, I probably wouldn’t have been in the right mindset to photograph.)

We arrived to find the Milky Way glowing brightly above the caldera and immediately started shooting. Because I don’t have as many horizontal compositions of the caldera as vertical, I started horizontal. By the time I’d captured a half dozen or so frames, a heavy mist dropped into the caldera to quickly obscure the entire view (one more example of our utter helplessness to the whims of Nature).

In this frame I went quite wide, not only to capture as much of the Milky Way as possible, but also to include all of the thin cloud layer painted orange by the light of the caldera’s fire. This is a single click (no blending of multiple images), though I did clone just a little bit of color back into the hopelessly blown center of the volcano’s flame.

A Kilauea Gallery

Click and image for a larger view, and to enjoy the slide slow