Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Gifts From Heaven

Posted on November 3, 2024

Heaven Sent, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS Above the Sierra Crest, Alabama Hills

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 3200

f/4

5 seconds

As much for its (apparently) random arrival as its ethereal beauty, the appearance of a comet has always felt to me like a gift from the heaven. Once a harbinger of great portent, scientific knowledge has eased those comet fears, allowing Earthlings to simply appreciate the breathtaking display.

Unfortunately, scientific knowledge does not equal perfect knowledge. So, while a great comet gives us weeks, months, or even years advance notice of its approach, we can never be certain of how the show will manifest until the comet actually arrives. For every Comet Hale-Bopp, that gave us nearly two years warning before becoming one of the most widely viewed comets in human history, we get many Comet ISONs, which ignited a media frenzy more than a year before its arrival, then completely fizzled just as the promised showtime arrived. ISON’s demise, as well as many highly anticipated comets before and after, taught me not to temper my comet hopes until I actually put eyes on the next proclaimed “comet of the century.” Nevertheless, great show or not, the things we do know about comets—their composition, journey, arrival, and (sometimes) demise—provide a fascinating backstory.

In the simplest possible terms, a comet is a ball of ice and dust that’s (more or less) a few miles across. After languishing for eons in the coldest, darkest reaches of the Solar System, perhaps since the Solar System’s formation, a gravitational nudge from a passing star sends the comet hurtling sunward, following an eccentric elliptical orbit—imagine a stretched rubber band. Looking down on the entire orbit, you’d see the sun tucked just inside one extreme end of the ellipse.

The farther a comet is from the sun, the slower it moves. Some comets take thousands, or even millions, of years to complete a single orbit, but as it approaches the sun, the comet’s frozen nucleus begins to melt. Initially, this just-released material expands only enough to create a mini-atmosphere that remains gravitationally bound to the nucleus, called a coma. At this point the tail-less comet looks like a fuzzy ball when viewed from Earth.

This fuzzy phase is usually the state a comet is in when it’s discovered. Comets are named after their discoverers—once upon a time this was always an astronomer, or astronomers (if discovered at the same time by different astronomers), but in recent years, most new comets are discovered by automated telescopes, or arrays of telescopes, that monitor the sky, like ISON, NEOWISE, PANSTARRS, and ATLAS. Because many comets can have the same common name, astronomers use a more specific code assembled from the year and order of discovery.

As the comet continues toward the sun, the heat increases further and more melting occurs, until some of the material set free is swept back by the rapidly moving charged particles of the solar wind, forming a tail. Pushed by the solar wind, not the comet’s forward motion, the tail always fans out on the side opposite the sun—behind the nucleus as the comet approaches the sun, in front of the comet as it recedes.

Despite accelerating throughout its entire inbound journey, a comet will never move so fast that we’re able to perceive its motion at any given moment. Rather, just like planets and our moon, a comet’s motion relative to the background stars will only be noticeable when viewed from one night to another. And like virtually every other object orbiting the sun, a comet doesn’t create its own light. Rather, the glow we see from the coma and tail is reflected sunlight. The brilliance of its display is determined by the volume and composition of the material freed and swept back by the sun, as well as the comet’s proximity to Earth. The color reflected by a comet’s tail varies somewhat depending on its molecular makeup, but usually appears as some shade of yellow-white.

In addition to the dust tail, some comets exhibit an ion tail that forms when molecules shed by the comet’s nucleus are stripped of electrons by the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Being lighter than dust molecules, these ions are whisked straight back by the solar wind. Instead of fanning out like the dust tail, these gas ions form a narrow tail that points directly away from the sun. Also unlike the dust tail that shines by reflected light, the ion tail shines by fluorescence, taking on a blue color courtesy of the predominant CO (carbon monoxide) ion.

One significant unknown upon discovery of a new comet is whether it will survive its encounter with the sun at all. While comets that pass close to the sun are more likely to shed large volumes of ice and dust, many sun-grazing comets approach so close that they’re overwhelmed by the sun’s heat and completely disintegrate.

With millions of comets in our Solar System, it would be easy to wonder why they’re not a regular part of our night sky. Actually, Earth is visited by many comets each year, though most are so small, and/or have made so many trips around the sun that they no longer have enough material to put on much of a show. And many comets never get close enough to the sun to be profoundly affected by its heat, or close enough to Earth to shine brightly here.

Despite all the things that can go wrong, every once in a while, all the stars align (so to speak), and the heavens assuage the disappointment of prior underachievers with a brilliant comet. Early one morning in 1970, my dad woke me and we went out in our yard to see Comet Bennett. This was my first comet, a sight I’ll never forget. I was disappointed by the faint smudges of Comet Kohoutek in 1973 (a complete flop compared to its advance billing), and Halley’s Comet in 1986 (just bad orbital luck for Earthlings). Comet Hale-Bopp in 1996 and 1997 was wonderful, while Comet ISON in 2012 disintegrated before it could deliver on its hype.

In 2013 Comet PANSTARRS didn’t put on much of a naked-eye display, but on its day of perihelion, I had the extreme good fortune to be atop Haleakala on Maui, virtually in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. Even though I couldn’t see the it, using a thin crescent moon I knew to be just 3 degrees from the comet to guide me, I was able to photograph PANSTARRS and the moon together. Then, in the dismal pandemic summer of 2020, Comet NEOWISE surprised us all to put on a beautiful show. I made two trips to Yosemite to photograph it, then was able to photograph it one last time at the Grand Canyon shortly before it faded from sight.

October 2024 promised the potential for two spectacular comets, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS (C/2023 A3) in the first half of the month, and Comet ATLAS (C/2024 S1) at the end of the month. Alas, though this second comet had the potential to be much brighter, it pulled an Icarus and flew too close to the sun (RIP). But Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was another story, brightening beyond expectations.

I shared the story of my trip to photograph Tsuchinshan–ATLAS in my October 16 I’m Not Crazy, I Swear… blog post, but have a couple of things to add about this image. First is how important it is to not get so locked into one great composition that you neglect capturing variety. I captured this wider composition before the image I shared a couple of weeks ago, and was pretty thrilled with it—thrilled enough to consider the night a great success. But I’m so glad that I changed lenses and got the tighter vertical composition shortly before the comet’s head dropped out of sight.

And second is the clearly visible anti-tail that was lost in thin haze near the peaks in my other image. An anti-tail is a faint, post-perihelion spike pointing toward the sun in some comets, caused when larger particles from the coma, too big to be pushed by the solar wind, are left behind. It’s only visible from Earth when we pass through the comet’s orbital plane. Pretty cool.

When will the next great comet arrive? No one knows, but whenever that is, I hope I’ve kindled enough interest that you make an effort to view it. But if you plan to chase comets, either to photograph or simply view, don’t forget the wisdom of astronomer and comet expert, David Levy: “Comets are like cats: they have tails, and do precisely what they want.”

Join me in my Eastern Sierra photo workshop

More Gifts From Heaven

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

I’m Not Crazy, I Swear…

Posted on October 16, 2024

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and Mt. Whitney, Alabama Hills, California

Sony α1

Sony 100-400 GM

5 seconds

f/5.6

ISO 3200

Crazy is as crazy does

In college, my best friend and I drove from San Francisco to San Diego so he could attend a dental appointment he’d scheduled before his recent move back to the Bay Area. We drove all night, 10 hours, arriving at 7:55 a.m. for his 8:00 a.m. appointment (more luck than impeccable timing). I dozed in the car while he went in; he was out in less than an hour, and we drove straight home. I remember very little of the trip, except that each of us got a speeding ticket for our troubles. Every time I’ve told that story, I’ve dismissed it with a chuckle as the foolishness of youth. Now I’m not so sure that youth had much to do with it at all.

I’m having second thoughts on the whole foolishness of youth thing because on Monday, my (non-photographer) wife and I drove nearly 8 hours to Lone Pine so I could photograph Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS setting behind Mt. Whitney. We arrived at my chosen location in the Alabama Hills about 15 minutes after the 6:20 sunset, then waited impatiently for the sky to darken enough for the comet to appear. I started photographing at around 7:00, and was done when the comet’s head dropped below Mt. Whitney at 7:30. After spending the night in Lone Pine, we left for home first thing the next morning, pulling into the garage just as the sun set. For those who don’t want to do the math, that’s 16 hours on the road for 30 minutes of photography.

In my defense, for this trip I had the good sense (and financial wherewithal) to get a room in Lone Pine Monday night, and didn’t get pulled over once. That this might have been a crazy idea never occurred to me until I was back at the hotel, and that was only in the context of how the story might sound to others—in my mind this trip was worth every mile, and I have the pictures to prove it.

I say that fully aware that my comet pictures will no doubt be lost in the flood of other Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS images we’ll see over the next few weeks, many no doubt far more spectacular than mine. My excitement with the fruits of this trip is entirely personal, and to say I’m thrilled to have witnessed and photographed another comet would be an understatement—especially in light of last month’s Image of the Month e-mail citing comets as one of the three most beautiful celestial subjects I’ve ever witnessed. And of those three, comets feel the most personal to me.

Let me explain

When I was ten, my best friend Rob and I spent most of our daylight hours preparing for our spy careers—crafting and trading coded messages, surreptitiously monitoring classmates, and identifying “secret passages” that would allow us to navigate our neighborhood without being observed. But after dark our attention turned skyward. That’s when we’d set up my telescope (a castoff generously gifted by an astronomer friend from my dad’s Kiwanis Club) on Rob’s front lawn (his house had a better view of the sky than mine) to scan the heavens hoping that we might discover something: a comet, quasar, supernova, black hole, UFO—it didn’t really matter. And repeated failures didn’t deter us.

Nevertheless, our celestial discoveries, while not Earth-changing, were personally significant. Through that telescope we saw Jupiter’s moons, Saturn’s rings, and the changing phases of Venus. We also learned to appreciate the vastness of the universe with the observation that, despite their immense size, stars never appeared larger than a pinpoint, no matter how much magnification we threw at them.

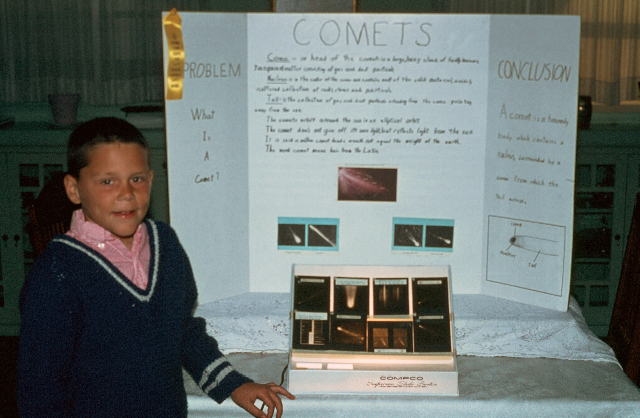

To better understand what we saw, Rob and I turned to illustrated astronomy books. Pictures of planets, galaxies, and nebula amazed us, but we were particularly drawn to the comets: Arend-Roland, Ikeya–Seki, and of course the patriarch of comets, Halley’s Comet (which we learned was scheduled to return in 1986, an impossible wait that might as well have been infinity). With their glowing comas and sweeping tails, it was difficult to imagine that anything that beautiful could be real. When it came time to choose a subject for the annual California Science Fair, comets were an easy choice. And while we didn’t set the world on fire with our project presentation, Rob and I were awarded a ribbon of some color (it wasn’t blue), good enough to land us a spot in the San Joaquin County Fair. (Edit: Uncovering the picture, I see now that our ribbon was yellow.)

Here I am with the fifth grade science project that started it all. (This is only half of the creative team—somewhere there’s a picture that includes Rob.)

The next milestone in my comet obsession occurred a few years later, after my family had moved to Berkeley and baseball had taken over my life. One chilly winter morning my dad woke me and urged me outside to view what I now know was Comet Bennett. Mesmerized, my smoldering comet interest flamed instantly, expanding to include all things astronomy. It stayed with me through high school (when I wasn’t playing baseball), to the point that I actually entered college with an astronomy major that I stuck with for several semesters, until the (unavoidable) quantification of the concepts I loved sapped the joy from me.

While I went on to pursue other things, my affinity for astronomy continued, and comets in particular remained special. Of course with affection comes disappointment: In 1973 Kohoutek fizzled spectacularly, a failure that somewhat prepared me for Halley’s anticlimax in 1986.

By the time Halley’s arrived, word had come down that it was poorly positioned for its typical display (“the worst viewing conditions in 2,000 years”), making it barely visible this time around, but I can’t wait until 2061! (No really—I can’t wait that long. Literally.) Nevertheless, venturing far from the city lights one moonless January night, I found great pleasure locating without aid (after much effort), Halley’s faint smudge in Aquarius.

After many years with no naked-eye comets of note, 1996 arrived with the promise of two great comets. While cautiously optimistic, Kohoutek’s scars prevented me from getting sucked in by the media frenzy. So imagine my excitement when, in early 1996, Comet Hyakutake briefly approached the brightness of Saturn, with a tail stretching more than twenty degrees (forty times the apparent width of a full moon).

But as beautiful as it was, Hyakutake proved to be a mere warm-up for Comet Hale-Bopp, which became visible to the naked eye in mid-1996 and remained visible until December 1997—an unprecedented eighteen months. By spring of 1997 Hale-Bopp had become brighter than Sirius (the brightest star in the sky), its tail approaching 50 degrees. I was in comet heaven. But alas, family and career had preempted my photography pursuits and I didn’t photograph Hale-Bopp.

Comet opportunities again quieted after Hale-Bopp. Then, in early 2007, Comet McNaught caught everyone off-guard, intensifying unexpectedly to briefly outshine Sirius, trailing a thirty-five degree, fan-shaped tail. McNaught put on a much better show in the Southern Hemisphere; in the Northern Hemisphere, because of its proximity in the sky to the sun, it provided a very small window of visibility, and was easily lost in the bright twilight. This, along with its sudden brightening, prevented McNaught from becoming the media event Hale-Bopp was. I only found out about it by accident, on the last day it would be easily visible in the Northern Hemisphere. By then digital capture had rekindled my photography interest (understatement), so despite virtually no time to prepare, I grabbed my camera and headed to the foothills east of Sacramento, where I managed to capture the McNaught image I share in the gallery below—my first successful comet capture.

Following McNaught, I vowed not to be caught off guard by a comet again. After enduring the frustration of promising (over-hyped?) comets disintegrated by the sun (you broke my heart, Comet ISON), and seeing others’ images of spectacular Southern Hemisphere-only comets (I’m looking at you, Comet Lovejoy), my heart jumped when I came across a website proclaiming the approach of Comet PANSTARRS (a.k.a, C/2011 L4 in less glamorous astro-nerd parlance), discovered not by an individual, but by the Pan-STARRS automated telescope array atop Haleakala on Maui.

Researching further, I learned that PANSTARRS could (fingers crossed) hang low in the western sky at magnitudes brighter than Saturn, for about a week right around its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) in March 2013, remaining visible as it rises but dims over the following few weeks. Checking my calendar to see if I had any conflicts that week, I realized I’d be on Maui for my workshop during PANSTARRS’ perihelion! Turns out my first viewing of PANSTARRS was atop Haleakala, almost literally in the shadow of the telescope that discovered it. I also got to photograph a rapidly fading PANSTARRS above Grand Canyon on its way back to the farthest reaches of the Solar System.

Then, in 2020, came Comet NEOWISE to brighten our pandemic summer. I was able to make two trips to Yosemite and another to Grand Canyon to photograph NEOWISE (the Yosemite trips were for NEOWISE only).

One more time

Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS has been on my radar for at least a year, but not something I monitored closely until September, when it became clear that it was brightening as, or better than, expected. By the end of September I knew that the best Northern Hemisphere views of Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would be in mid-October, but since I was already in the Alabama Hills at the end of September, just a couple of days after the comet’s perihelion, I went out to look for it in the pre-sunrise eastern sky (opposite the gorgeous Sierra view to the west). No luck, but that morning only solidified my resolve to give it another shot when it brightened and returned to the post-sunset sky.

At that point I had no detailed plan, and hadn’t even plotted its location in the sky beyond knowing it would be a little above the western horizon shortly after sunset in mid-October. My criteria were a nice west-facing view, distant enough to permit me to use a moderate telephoto lens. After ruling out the California coast (no good telephoto subjects) and Yosemite Valley (no good west-facing views), I soon realized I’d be returning to the east side of the High Sierra.

At that point I started working on more precise coordinates and immediately eliminated my first (and closest) candidate, Olmsted Point, because the setting comet didn’t align with Half Dome. My next choice was Minaret Vista (near Mammoth), a spectacular view of the jagged Minaret range and nearby Mt. Ritter and Mt. Banner. This was a little more promising—the alignment wasn’t perfect, but it was workable. Then I looked at the Alabama Hills and Mt. Whitney and knew instantly I’d be reprising the long drive back down 395 to Lone Pine.

Though its intrinsic magnitude faded each day after its September 27 perihelion, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS’s apparent magnitude (visible brightness viewed from Earth) continued to increase until its closest approach to Earth on October 12. While its magnitude would never be greater than it was on October 12, the comet was still too close to the sun to stand out against sunset’s vestigial glow. But each night it climbed in the sky, a few degrees farther from the sun, toward darker sky.

Though Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would continue rising into increasingly dark skies through the rest of October, and each night would offer a longer viewing window than the prior night, I chose October 14 as the best combination of overall brightness and dark sky. An added bonus for my aspirations to photograph the comet with Mt. Whitney and the Sierra Crest would be the 90% waxing gibbous moon rising behind me, already high enough by sunset to nicely illuminate the peaks after dark, but still far enough away not to significantly wash out the sky surrounding the comet.

At my chosen spot, I set up two tripods and cameras, one armed with my Sony a7RV and 24-105 lens, the other with my Sony a1 and 100-400 lens. I selected that first location because it put the comet almost directly above Mt. Whitney, 16 degrees above the horizon, at 7 p.m. But since the Sierra crest rises about 10 degrees above the horizon when viewed from the Alabama Hills, I knew going in that the comet’s head would slip behind the mountains at 7:30, slamming shut my window of opportunity after only 30 minutes.

When it first appeared, Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was high enough that I mostly used my 24-105 lens. But as it dropped and moved slightly north (to the right), away from Whitney, we hopped in the car and raced about a mile south, to the location I’d chosen knowing that Tsuchinshan–ATLAS would align perfectly with Whitney as it dropped below the peaks. Most of my images from this location were captured with my 100-400 lens.

I manually focused on the comet’s head, or on a nearby relatively bright star, then checked my focus after each image. The scene continued darkening as I shot, and to avoid too much star motion I increased my ISO rather than extending my shutter speed.

As I photographed, I could barely contain my excitement at the image previews on my cameras’ LCD screens. Tsuchinshan–ATLAS and its long tail were clearly visible to my eyes, but the cameras’ ability to accumulate light made it much brighter than what we saw. The image I share today is one of my final images of the night. Even with a shutter speed of only 5 seconds, at a focal length of right around 200mm, if you look closely you’ll still see a little star motion.

My giddiness persisted on the drive back to Lone Pine and into our very nice (and hard earned) dinner. When our server expressed interest in the comet, I went out to the car and grabbed my camera to share my images with her. Whether or not the enthusiasm she showed was genuine, she received a generous tip for indulging me. And even though I usually wait until I’m home to process my images on my large monitor, I couldn’t help staying up well past lights-out to process this one image, just to reassure myself that I hadn’t messed something up (focus is always my biggest concern during a night shoot).

And finally…

FYI, neither Rob nor I became spies, but we have stayed in touch over the years. In fact, the original plan was for him to join me on this adventure, but circumstances interfered and he had to stay home. But we still have hopes for the next comet, which could be years away, or as soon as late this month….

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

My Comet History

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Ion the Prize

Posted on July 18, 2021

Comet NEOWISE With Ion Tail, Taft Point, Yosemite

Sony a7RIV

Sony 100-400 GM

6 seconds

F/5

ISO 12800

Comets were once harbingers of doom, so it’s likely that in times past the appearance of a bright comet coincident with a worldwide pandemic would have stoked great fear. Instead, (thanks to knowledge gained through centuries of scientific discovery) Comet NEOWISE infused a kernel of joy into an otherwise bleak year.

Spurred by the first NEOWISE anniversary earlier this month, over the previous week or two I revisited the images from last July’s four NEOWISE shoots (two in Yosemite, two at Grand Canyon) to see if I’d overlooked anything. It was great to mentally revisit those nights, which were each in their own way among the most memorable night sky experiences of my life:

- July 10, 2020: “I never dreamed it would be this bright”

- July 16, 2020: That ion tail!

- July 23, 2020: Hello Grand Canyon

- July 24, 2020: Farewell NEOWISE

On my search I found many process-worthy images, but most were fairly similar to what I already had. One exception is the image I share here. Rather than casting the magnificent comet in a costarring role with landscape and/or celestial icons (Half Dome, El Capitan, Grand Canyon, Big Dipper, Venus), NEOWISE is the one and only star of this image. And more than my other NEOWISE images, what sets this one apart is the spectacular ion tail.

Of my four NEOWISE shoots, the comet was probably at its most striking for my two in Yosemite—each for a different reason. My first NEOWISE experience came during a pre-sunrise visit to Glacier Point that coincided with the comet’s peak visibility.

While it had brightened to somewhere between magnitude 0 and 1 (the lower the magnitude, the brighter) shortly after its July 3 perihelion (closest approach to the sun), NEOWISE was too close to the sun to stand out in the against the brightening sky. But by the time of my Yosemite trip on July 10, NEOWISE had climbed out of the sun’s glow, while still shining in the magnitude 1 to 2 range—somewhere between the brightness of Spica and Polaris—making it easily the most prominent object in that part of the sky.

Six days later I returned to Yosemite, this time taking the one mile hike out to Taft Point to photograph NEOWISE above El Capitan after sunset. When the sky darkened, NEOWISE was clearly visible to the naked eye, but noticeably dimmer. But what made this night’s show special was the development of a spectacular ion tail. Faintly visible to the unaided eye, this new addition was a thing of beauty in my viewfinder and images.

I digress

I’m going to digress briefly to mention an important aspect of my photography that I’m not sure everyone shares. In the simplest possible terms, I can’t imagine photographing subjects—celestial, terrestrial, atmospheric—that I don’t understand. Rather than a personal “rule,” this need to understand my subjects is so ingrained in my personality that I didn’t fully appreciate its significance until recently.

My proclivity manifests in many ways, from obsessively buying geology books on every new location, to pouring over scientific articles explaining an obscure cloud formation, to mentally running orbital geometry in my head as I go to sleep (really). And sometimes understanding is the catalyst, inspiring me to pursue with my camera subjects that have fascinated me for years: lightning, solar eclipse, the aurora. (Still dreaming about that first tornado.)

My own internal connection between visual beauty and the natural phenomena that beauty represents probably explains why my blog is such an integral part of my photography. While I can capture nature’s visual gifts with my camera, I need my blog to connect it to the underlying processes. Another, no less important, component of blogging about my subjects is that researching and writing it often becomes as much of a learning experience for me as it is for my readers. (So thank you.)

But anyway…

If you follow me at all, you know my love of astronomy in general, and of comets in particular. So when I saw NEOWISE’s ion tail, I knew what it was, but wanted to more completely understand things like why a comet’s ion tail is always separated from its brighter dust tail, and why the ion tail appears blue in my images (is this real, a color temperature thing, or maybe some color artifact introduced in-camera?).

At risk of repeating myself, a comet is a lump of dust and ice in an extreme elliptical (it’ll be back) or parabolic (one-and-done) orbit of the sun. Most of the comet’s journey is pretty ordinary, but as it approaches the sun, things start to happen—its speed increases, and the sun’s heat starts melting the ice, freeing gas and dust molecules to form a fuzzy coma surrounding the frozen nucleus.

As the comet accelerates toward the sun, the temperature continues rising and the rate of liberated molecules increases. The mass and momentum of the comet’s nucleus allows it to continue on its orbital path, but the freed dust molecules, now under the influence of the solar wind, are nudged back, away from the sun: a tail is born.

Over time this dust tail grows and spreads, becoming the signature feature of most comets. Like most of the comet, the dust tail doesn’t create its own light, but rather is illuminated solely reflected sunlight. Varying somewhat with the composition of its molecules, the dust tail will appear yellow-white to our eyes.

But I’ve saved the best for last. Gas molecules shed by the comet’s nucleus, being lighter than dust molecules, are whisked straight back by the solar wind. Instead of fanning out like the dust tail, these gas molecules form a narrow ion tail that points directly away from the sun. Some of these gas molecules are ionized (stripped of an electron). Unlike the dust tail that shines by reflected light, the ion tail shines by fluorescence, taking on a blue color courtesy of the predominant CO (carbon monoxide) ion.

Of course there’s a time for pondering the marvels of nature, and a time for simply basking in its beauty. So as I was photographing this scene, I wasn’t thinking about all the physics and chemistry unfolding before me, I was focused on capturing the product of the underlying processes (the comet) and its relationship with the surrounding landscape. On this night most of my images were variations of NEOWISE with El Capitan and/or the nearby Big Dipper. But I’m glad I took the time to include a few frames that put this magnificent comet itself front-and-center.

Sign-up to receive my Image of the Month e-mail

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A Comet NEOWISE Retrospective

Category: Comet, Comet NEOWISE, Sony 100-400 GM, Sony a7RIV, stars, Yosemite Tagged: astrophotography, Comet, Comet NEOWISE, nature photography, Yosemite

One Quiet Night on the Rim

Posted on October 25, 2020

Comet NEOWISE in the Clouds, Navajo Point, Grand Canyon

Sony a7SII

Sony 20mm f/1.8 G

20 seconds

F/1.8

ISO 8000

One of the great joys of making my living photographing nature is the opportunity to witness the most beautiful scenes in the world. The problem is, most of these places aren’t a secret, so it can be difficult to have them at their best: alone. Fortunately, the best time to take pictures is usually the worst time to be outside—like rain and snow, freezing cold, and ungodly hours. To this list of good times to take pictures, this summer I added one more: During a global pandemic.

In July my brother Jay and I made two visits to Yosemite to photograph Comet NEOWISE, and one to the Grand Canyon to photograph lightning. With the world largely shutdown due to the pandemic, we got to experience firsthand what it must have been like to visit these congested summer destinations before they were overrun by tourists. I remember circling Yosemite Valley on our first visit and feeling disoriented by the lack of cars and the abundance of relaxed wildlife just chilling in the meadows and on the roadside. And at the Grand Canyon, with just two days notice, I was able to get a room just a few hundred yards from the rim for a rate I’d have been thrilled to get in the dead of winter.

One particular highlight in this year achingly short of highlights came on our last night at the Grand Canyon. Though we’d made this trip primarily because lightning was in the forecast, I also knew that rapidly fading Comet NEOWISE would be hanging in the northern sky after sunset. Unfortunately, the vestiges of those thunderstorms we’d come to photograph blocked most of our comet views. We struck out completely on the first night, but the second night we enjoyed a short but sweet comet shoot at Grandview Point before the clouds moved back in. The arrival of clouds following a successful shoot is often enough to send me packing, but having not seen a single other person our entire time out there, I wasn’t quite ready to let go of the opportunity to experience glory the Grand Canyon in absolute solitude.

Instead of driving back to our hotel, we continued east along the rim, all the way to the end of the road (normally this road continues to Cameron and beyond, but it was closed near the park’s east entrance), ending up at Navajo Point. I had little hope for more glimpses of NEOWISE, but with a view that really didn’t need any help, I set up my camera anyway. Though it was impossible for Navajo Point to be any more empty or quiet than Grandview Point had been, I think the distance from civilization made us feel even more isolated.

Beneath a mix of clouds and stars, Jay and I photographed and gazed for about a half hour. With the canyon illuminated by the light of a 25% waning crescent moon, we could see clearly all the way down to the river. But my Sony a7SII (long my dedicated night camera, since replaced by the Sony a7SIII) did even better, pulling seemingly invisible detail from the darkest shadows. Just as we were about to leave, the clouds parted and there was NEOWISE, as if it wanted to say farewell before embarking on its multi-millennia journey to the fringe of our solar system. I clicked a few frames before the clouds snapped shut and bid my friend goodbye.

I’m not going to pretend that the pandemic was a good thing, or that I’m in any way happy that it happened, but I’ve always believed that our state of mind is what we make it. Like everyone else, I can’t wait for things to return to normal, but when I find myself dwelling on the countless negatives of 2020, I try to remind myself of the year’s blessings that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. Perhaps small consolation in light of all the loss, but this night on the rim of the Grand Canyon was one such blessing, not just a high point of my year, but a high point of my life.

One Last Look at Comet NEOWISE (Yosemite and Grand Canyon)

Category: Colorado River, Comet, Comet NEOWISE, Grand Canyon, Navajo Point, Sony 20mm f/1.8 G, Sony a7S II, stars Tagged: astrophotography, Comet, Comet NEOWISE, Grand Canyon, nature photography, Navajo Point, stars

Breathtaking Comet NEOWISE

Posted on July 12, 2020

Comet NEOWISE and Venus, Half Dome from Glacier Point, Yosemite

Sony a7RIV

Sony 24-105 G

10 seconds

F/5.6

ISO 3200

When I was ten, my best friend Rob and I spent most of our daylight hours preparing for our spy careers—crafting and exchanging coded messages, surreptitiously monitoring classmates, and identifying “secret passages” that would allow us to navigate our neighborhood without being observed. But after dark our attention turned skyward. That’s when we’d set up my telescope (a castoff generously gifted by an astronomer friend of my dad) on Rob’s front lawn to scan the heavens in the hope that we might discover something: a supernova, comet, black hole, UFO—it didn’t really matter.

Our celestial discoveries, while not Earth-changing, were personally significant. Through that telescope we saw Jupiter’s moons, Saturn’s rings, and the changing phases of Venus. We also learned to appreciate the vastness of the universe with the insight that, despite their immense size, stars never appeared larger than a pinpoint, no matter how much magnification we threw at them.

Here I am with the fifth grade science project that started it all. (This is only half of the creative team—somewhere there’s a picture that includes Rob.)

To better understand what we saw, Rob and I turned to astronomy books. Pictures of planets, galaxies, and nebula amazed us, but we were particularly drawn to the comets: Arend-Roland, Ikeya–Seki, and of course the patriarch of comets, Halley’s Comet (which wouldn’t return until 1986, an impossible wait that might as well have been infinity). With their brilliant comas and sweeping tails, it was difficult to imagine that anything that beautiful could be real. When the opportunity came to do a project to enter in our school’s Science Fair, comets were an easy choice. And while we didn’t set the world on fire with our project presentation, Rob and I were awarded a yellow ribbon, good enough to land us a spot in the San Joaquin County Fair.

The next milestone in my comet obsession occurred a few years later, after my family had moved to Berkeley and baseball had taken over my life. One chilly winter morning my dad woke me and urged me outside to view what I now know was Comet Bennett. Mesmerized, my smoldering comet fascination flamed instantly, expanding to include all things celestial, and stayed with me through high school (when I wasn’t playing baseball).

I can trace my decision to enter college with an astronomy major all the way back to my early interest in the night sky in general, and comets in particular. I stuck with the astronomy major for several semesters, until the (unavoidable) quantification of magnificent concepts sapped the joy from me.

Though I went on to pursue other interests, my affinity for astronomy hadn’t been dashed, and comets in particular remained special. Of course with affection comes disappointment: In 1973 Comet Kohoutek broke my heart, a failure that somewhat prepared me for Halley’s anticlimax in 1986. By the time Halley’s arrived, word had come down that it was poorly positioned for its typical display (“the worst viewing conditions in 2,000 years”), that it would be barely visible this time around (but just wait until 2061!). Nevertheless, venturing far from the city lights one moonless January night, I found great pleasure locating (with much effort) Halley’s faint smudge in Aquarius.

After many years with no naked-eye comets of note, 1996 arrived with the promise of two great comets. While cautiously optimistic, Kohoutek’s scars prevented me from getting sucked in by the media frenzy. So imagine my excitement when, in early 1996, Comet Hyakutake briefly approached the brightness of Saturn, with a tail stretching more than twenty degrees (forty times the apparent width of a full moon). But as beautiful as it was, Hyakutake proved to be a mere warm-up for Comet Hale-Bopp, which became visible to the naked eye in mid-1996 and remained visible until December 1997—an unprecedented eighteen months. By spring of 1997 Hale-Bopp had become brighter than Sirius (the brightest star in the sky), its tail approaching 50 degrees. I was in comet heaven.

Things quieted considerably comet-wise after Hale-Bopp. Then, in 2007, Comet McNaught caught everyone off-guard, intensifying unexpectedly to briefly outshine Sirius, trailing a thirty-five degree, fan-shaped tail. But because of its proximity to the sun, Comet McNaught had a very small window of visibility in the Northern Hemisphere and was easily lost in the bright twilight—it didn’t become anywhere near the media event Hale-Bopp did. I only learned about it on the last day it would be easily visible in the Northern Hemisphere. With little time to prepare, I grabbed my camera and headed to the foothills east of Sacramento, where I managed to capture a few faint images and barely pick the comet out of the twilight with my unaided eyes. McNaught saved its best show for the Southern Hemisphere, where it became one of the most beautiful comets ever to grace our skies (google Comet McNaught and you’ll see what I mean).

After several years of comet crickets, in 2013 we were promised two spectacular comets, PanSTARRS and ISON. A fortuitous convergence of circumstances allowed me to photograph PanSTARRS from the summit of Haleakala on Maui—just 3 degrees from a setting crescent moon, it was invisible to my eye, but beautiful to my camera. Comet ISON on the other hand, heralded as the most promising comet since Hale-Bopp, pulled an Icarus and and disintegrated after flying too close to the sun.

Since 2013 Earth has been in a naked-eye comet slump. Every once in a while one will tease us, then fizzle. In fact, 2020 has already seen two promising comets flop: Comets Atlas and Swan. So when Comet NEOWISE was discovered in March of this year, no one got too excited. But by June I started hearing rumblings that NEOWISE might just sneak into the the naked-eye realm. Then we all held our breath while it passed behind the sun on July 2.

Shortly after NEOWISE’s perihelion, astronomers confirmed that it had survived, and images started popping up online. The first reports were that NEOWISE was around magnitude 2 (about as bright as Polaris, the North Star) and showing up nicely in binoculars and photos. Unfortunately, NEOWISE was so close to the horizon that it was washed-out to the naked eye by the pre-sunrise twilight glow.

Based on my experience with PanSTARRS, a comet I’d captured wonderfully when I couldn’t see it in the twilight glow, I started making plans to photograph Comet NEOWISE. But I needed to find a vantage point with a good view of the northeast horizon, not real easy in Sacramento, where we’re in the shadow of the Sierra just east of town. After doing a little plotting, I decided my best bet would be to break my stay-away-from-Yosemite-in-summer vow and try it from Glacier Point. Glacier Point is elevated enough to offer a pretty clear view of the northeast horizon, and from there Half Dome and the comet would align well enough to easily include both in my frame.

While Yosemite is currently under COVID restrictions that require reservations (sold out weeks in advance) to enter, I have a CUA (Commercial Use Authorization that allows me to guide photo workshops) that gives me access to the park if I follow certain guidelines. So, after checking with my NPS Yosemite CUA contact to make sure all my permit boxes were checked, my brother Jay and I drove to the park on Thursday afternoon, got a room just outside the park, and went to bed early.

The alarm went off at 2:45 the next morning, and by 2:55 we were on the road to Glacier Point. After narrowly averting one self-inflicted catastrophe (in the absolute darkness, I missed a turn I’ve been taking for more than 40 years), by 4:00 we were less than a mile from Glacier Point and approaching Washburn Point, the first view of Half Dome on Glacier Point Road. Unable to resist the urge to peek (but with no expectation of success), I quickly glanced in that direction and instantly saw through my windshield Comet NEOWISE hanging above Mt. Watkins, directly opposite Tenaya Canyon from Half Dome. I knew there’d be a chance NEOWISE would be naked-eye visible, but I never dreamed it would be this bright.

Everything after that is a blur (except my images, thankfully). Jay and I rushed out to the railed vista at the far end of Glacier Point and were thrilled to find it completely empty. We found Half Dome beautifully bookended by Comet NEOWISE on the left, and brilliant Venus on the right. I set up two tripods, one for my Sony a7RIV and 24-105 G lens, and one for my Sony a7RIII and Sony 100-400 GM lens. Shut out of all the locations I love to photograph by COVID-19, I hadn’t taken a serious picture since March, so I composed and focused carefully to avoid screwing something up. The image I share here is one of the first of the morning, taken with my a7RIV and 24-105.

By 4:30 or so (about 80 minutes before sunrise) the horizon was starting to brighten, but the comet stayed very prominent and photogenic until at about 4:50 (about an hour before sunrise). When we wrapped up at around 5:00, NEOWISE was nearly washed out to the unaided eye; while our cameras were still picking it up, we knew that the best part of the show was over.

It’s these experiences that so clearly define for me the reason I’m a photographer. Because I’ve always felt that photography, more than anything else, needs to make the photographer happy (however he or she defines happiness), many years ago I promised myself that I’d only photograph what I want to photograph, that I’d never take a picture just because I thought it would earn me money or acclaim. My own photographic happiness comes from nature because I grew up outdoors (okay, not literally, but outdoors is where my best memories have been made) and have always been drawn to the natural world—not merely its sights, but the natural processes and forces that, completely independent of human intervention and influence, shape our physical world.

I think that explains why, rather than settle for pretty scenes, I try to capture the interaction of dynamic natural processes with those scenes. The moon and stars, the northern lights, sunrise and sunset color, weather events like rainbows and lightning—all of these phenomena absolutely fascinate me, and the images I capture are just a small part of my relationship with them. I can’t imagine photographing something that doesn’t move me enough to understand it as thoroughly as I can, and enjoy learning about my subjects as much as I enjoy photographing them.

The converse of that need to know my subjects is a need to photograph those things that drive me to understand them. Most of the subjects that draw me are relatively easy to capture with basic preparation, some effort, and a little patience. But the relative rarity of a few phenomena make photographing them a challenge. This is especially true of certain astronomical events. I’m thinking specifically about the total solar eclipse that I finally managed to photograph in 2017, and the northern lights, which finally found my sensor last year. But comets have proven even more elusive, and while I’ve seen a few in my life, and even photographed a couple, I’ve never had what I’d label an “epic” comet experience that allowed me to combine a beautiful comet with a worthy foreground. Until this week. And I’m one happy dude.

Comet Class

Comets in General

I want to tell you how to photograph Comet NEOWISE, but first I’m going to impose my personal paradigm and explain comets.

A comet is a ball of ice and dust a few miles across (more or less), typically orbiting the sun in an eccentric elliptical orbit: Imagine a circle stretched way out of shape by grabbing one end and pulling–that’s what a comet’s orbit looks like. Looking down on the entire orbit, you’d see the sun tucked just inside one extreme end of the ellipse. (Actually, some comets’ orbits are parabolic, which means they pass by once and then move on to ultimately exit our solar system.)

The farther a comet is from the sun the slower it moves, so a comet spends the vast majority of its life in the frozen extremities of the solar system. Some periodic comets take thousands or millions of years to complete a single orbit; others complete their trip in just a few years.

As a comet approaches the sun, stuff starts happening. It accelerates in response to the sun’s increased gravitational pull (but just like the planets, the moon, or the hour hand on a clock, a comet will never move so fast that we’re able to visually discern its motion). And more significantly, increasing solar heat starts melting the comet’s frozen nucleus. Initially this just-released material expands to create a mini-atmosphere surrounding the nucleus; at this point the comet looks like a fuzzy ball when viewed from Earth. As the heat increases, some of the shedding material is set free and dragged away by the solar wind (charged particles) to form a tail that glows with reflected sunlight (a comet doesn’t emit its own light) and always points away from the sun. The composition and amount of material freed by the sun, combined with the comet’s proximity to Earth, determines the brilliance of the display we see. While a comet’s tail gives the impression to some that it’s visibly moving across the sky, a comet is actually about as stationary against the stellar background as the moon and planets—it will remain in one place relative to the stars all night, then appear in a slightly different place the next night.

With millions of comets in our Solar System, it would be natural to wonder why they’re not regular visitors to our night sky. Actually, they are, though most comets are so small, and/or have made so many passes by the sun, that their nucleus has been stripped of reflective material and they just don’t have enough material left to put on much of a show. And many comets don’t get close enough to the sun to be profoundly affected by its heat, or close enough to Earth to stand out.

Most of the periodic comets that are already well known to astronomers have lost so much of their material that they’re too faint to be seen without a telescope. One notable exception is Halley’s Comet, perhaps the most famous comet of all. Halley’s Comet returns every 75 years or so and usually puts on a memorable display. Unfortunately, Halley’s last visit, in 1986, was kind of a dud; not because it didn’t perform, but because it passed so far from Earth that we didn’t have a good view of its performance on that pass.

Comet NEOWISE in particular (and some tips for photographing it)

Comet NEOWISE is a periodic comet with an elliptical orbit that will send it back our way in about 6700+ years. On it’s current iteration, NEOWISE zipped by the sun on July 2 and is on its way back out to the nether reaches of our solar system. The good news is that NEOWISE survived the most dangerous part of its visit, its encounter with the sun. The bad news is that NEOWISE’s intrinsic brightness decreases as it moves away from the sun. But if all goes well, we’ll be able to see it without a telescope, camera, or binoculars for at least a few more weeks. And it doesn’t hurt that until perigee on July 22, NEOWISE is still moving closer to Earth.

Because a comet’s tail always points away from the sun, and NEOWISE is now moving away from the sun, it’s actually following its tail. If you track the comet’s position each night, you’ll see that it rises in the northeast sky before sunrise, which makes it a Northern Hemisphere object (the Southern Hemisphere has gotten the best 21st century comets, so it’s definitely our turn). Each morning NEOWISE will rise a little earlier, placing it farther from the advancing daylight than the prior day, so even if its intrinsic brightness is waning, it should stand out better because it’s in a darker part of the sky. And as a bonus, the moon is waning, so until the new moon on July 21, there will be no moonlight to compete with NEOWISE.

Until now, Comet NEOWISE has been an exclusively early morning object, but that’s about to change as it climbs a little higher each day. Starting tonight (July 12), you might be able to see it shortly after sunset near the northwest horizon, and each night thereafter it will be a little higher in the northwest sky. Your best chance to view Comet NEOWISE in the evening is to find an open view of the northwest sky, far from city lights.

Photographing Comet NEOWISE will require some night photography skill. Since the moon is waning, you won’t have the benefit of moonlight that I had when I photographed the comet in Yosemite on the morning of July 10, when the moon was about 75% full. This won’t be a huge problem if you just want to photograph NEOWISE against the stars, but if you want to include some landscape with it, your best bet may be to stick to silhouettes, or stack multiple exposures, one for the comet and one or more for the foreground.

To photograph it against the starry sky, I recommend a long telephoto to fill the frame as much as possible. If you want to include some landscape, go as wide as necessary, but don’t forget that the wider you go, the smaller the comet becomes. Whatever method you use to focus (even if you autofocus on the comet itself), I strongly recommend that you verify your focus each time you change your focal length. If you choose the multi-exposure blend approach, please, please, please, whatever you do, don’t blend a telephoto NEOWISE image with a wide angle image of the landscape (because I’ll know and will judge you for it).

Camera or not, I strongly encourage you to make an effort to see this rare and beautiful object, because you just don’t know when the next opportunity will arise—it could be next month, or it might not happen again in your lifetime.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

Gifts From Heaven

Category: Comet, Comet NEOWISE, Glacier Point, Half Dome, Moonlight, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7RIV, stars, Yosemite Tagged: Comet, Comet NEOWISE, Glacier Point, Half Dome, moonlight, nature photography, stars, Venus, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About