Clouds are Underrated

Posted on March 11, 2012

Blue skies and bright sunshine are great for tourists, but they can ruin a photographer’s day. Granted, warm sunrise and sunset light casts dramatic shadows and warms the landscape for a few quiet minutes at the beginning and end of the day. But when the sun is up, the light is harsh and tourists swarm like ants to a picnic.

On the other hand, an overcast sky diffuses sunlight, diminishes shadows, and softens the landscape. While diffuse overcast light isn’t usually as dramatic as warm early and late direct sunlight, it’s always wonderfully photographable. It also keeps the teeming masses at bay. If given a choice between dramatic sunrise and sunset light bookending a day of blues skies, or a full day of flat, overcast light, I’d take the overcast day without hesitation.

First Light, Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley: On most mornings, direct sunlight skims Mesquite Flat Dunes’ sandy undulations, etching straight lines and graceful curves that photographers crave.

Death Valley’s Mesquite Flat Dunes are gorgeous when the day’s first light peeks over the Funeral Mountains and skims the dunes’ pristine ridges and curves, casting extreme shadows that exaggerates everything wonderful about sand dunes. In an arid environment that rarely sees clouds, these dunes near Stovepipe Wells are a must-shoot for serious photographers.

But I’m afraid in their desire to duplicate the beautiful, high-contrast sunrise images that have preceded them, photographers overlook the possibilities when the sun doesn’t arrive. I love photographing sand dunes beneath cloudy skies, and can’t understand the disappointment I hear when dune photographers (who should know better) lament cloudy skies. I realize overcast doesn’t offer the kind of bold shadows that create the dramatic images everyone else has, but as someone who constantly looks to photograph things a little differently than others have (of course that doesn’t make me unique), I just love these dunes in more subdued light.

In last month’s Death Valley workshop, it was pretty obvious that we wouldn’t be seeing much sun at sunrise on the morning of our dune shoot. Nevertheless, as we prepared for the one mile trek in the pre-dawn darkness, I reassured everyone that they were in for a treat. (I couldn’t help but wonder if they thought I was selling them a bill of goods, but everyone seemed in good spirits as we followed our flashlights across the sand.)

I’d selected a relatively remote location that tends to offer a better chance of solitude and sand unmarred by footprints. Getting there is slightly more work, but nothing more than anyone in the group could handle. The slightly extra effort turned out to be worth it, as we found only a handful of footprints and saw no other photographers while we were out there.

While it was still fairly dark as we scaled the final dune and prepared to set up, flashlights were no longer necessary. Not only is shadowless twilight vastly underrated for photography, starting early gives everyone a chance to familiarize themselves with the scene before the sky starts to light up, so I encouraged everyone to start shooting as soon as they were ready.

As expected, the rising sun never made its way directly onto the dunes that morning, but it did find enough openings to paint the clouds in all directions with vivid reds and pinks, a rare treat in Death Valley (and an unexpected bonus). The image at the top of the page was captured about forty-five minutes after sunrise–without clouds, the best light would have been long passed by then. To emphasize the delicate, repeating ridges in the sand, I dropped my tripod as close to sand-level as it would go, stopping down to f16 and focusing maybe twenty feet in front of me to maximize depth of field. I used the diagonal “valley” in the middle distance to lead the eye through the scene, and because the sky wasn’t particularly interesting, relegated it to a thin strip above Death Valley Buttes and the Funeral Mountains.

All in all, a nice morning, and (I think) a good lesson for all.

Reflecting on reflections

Posted on March 4, 2012

Winter Reflection, El Capitan, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

1.3 seconds

F/16.0

ISO 100

19 mm

What is it about reflections? I don’t know about you, but I absolutely love them–I love photographing them, and I love just watching them. Like a good metaphor in writing, a reflection is an indirect representation that can be more powerful than its literal counterpart. In that regard, part of a reflection’s tug is its ability to engage the brain in different ways than we’re accustomed: Rather than processing the scene directly, we first must mentally reassemble the reverse world of a reflection, and in the process perhaps see the scene a little differently.

Because a camera renders our dynamic world in a static medium, water’s universal familiarity makes it a powerful tool for photographers. We blur or freeze in space a plummeting waterfall to convey a sense of motion that conjures auditory memories of moving water. Conversely, the mere image of a mountain reflecting in a lake can convey stillness and engender the peace and tranquility of standing on the lakeshore.

This El Capitan winter reflection is another from last month’s Yosemite winter workshop. Arriving at Tunnel View before sunrise, we found a world covered in snow and smothered by clouds. But as daylight rose, the clouds parted and we were treated to a classic Yosemite Valley clearing storm scene. The photography was still great when I herded everyone away from Tunnel View so we’d have time to capture as much ephemeral grandeur as possible in the limited time before the snow disappeared. I tell my groups that, while the photography is still great where we are, it’s great elsewhere too. This approach ensure that not only does everyone get beautiful images, they get a variety of beautiful images.

El Capitan Bridge was our second stop after Tunnel View. El Capitan is so large and close here that capturing it and its reflection in a single frame is impossible without a fisheye lens, or stitching multiple images. But sometimes the desire to capture everything the eye sees introduces distractions. Feeling a bit rushed, I inhaled and forced myself to slow down and simply absorbed moment, soon realizing that it was the reflection that moved me most.

I attached my 17-40 and tried fairly wide vertical and horizontal compositions that highlighted the best parts of the scene, twisting my polarizer in search of an orientation that captured the the reflection while still revealing the interesting world beneath the surface. Of the dozen or so frames that resulted, this may be my favorite for the way it conveys everything in those few sunlit, snowy minutes when the world seemed silent and pure.

* * * *

A note to you skeptics: I’m asked from time-to-time why the trees are white, while their reflection is green. This actually makes perfect sense once you realize that you’re looking at the top of the snow-covered branches, while the reflection is of the underside of the branches, which are not covered with snow.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A gallery of reflections

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

If you can’t beat ’em…

Posted on March 1, 2012

If it weren’t for Tunnel View on the Wawona Road, no doubt one of the most photographed vistas in the world, this view from Big Oak Flat Road, across the Merced River Canyon from Tunnel View, would probably be the Yosemite shot we all see. Visitors arriving from Highway 120 round a bend and are greeted with this view, their first inkling of Yosemite’s grandeur.

I’ve stopped here many times, but rarely photograph this view because it seems I always struggle with what to do with the foreground rocks and tree–composing wide enough to include them makes El Capitan, Half Dome, and Sentinel Dome quite small, and I just don’t think they’re interesting enough to occupy so much of the frame. But a couple of weeks ago, while guiding a private workshop student on a snowy morning, I found the entire scene etched in white and immediately saw the possibilities. Like magic, when adorned with a snowy veneer these foreground distractions became a worthy subject.

I moved as far back as the terrain would permit so I could increase my focal length and compress the distance separating the foreground and background. Even so, I was only able to go to 50mm, hardly a telephoto shot. Nevertheless, 50mm with subjects in my close foreground and distant background created depth of field problems. Whipping out my trusty iPhone hyperfocal app, I determined that I could make the scene work at 50mm and f16 if I was very careful with my focus point–focusing a little less than twenty feet away would give me sharpness from about eight feet to infinity. Because I had no way to measure the distance exactly (pacing it off would have ruined the pristine snow) and was more concerned about keeping the foreground sharp than I was about minor softness in El Capitan and Half Dome, I biased my estimate on the close side of twenty feet (making sure I focused between fifteen and twenty feet rather than between twenty and twenty-five feet).

All my previous images from this location have been telephoto shots the emphasize the strength of Half Dome, El Capitan, and Sentinel Dome. In fact, last May a rising crescent moon from this location gave me two of my favorite Yosemite images. But this time I was really happy for the opportunity to go wide and use these foreground features that had bothered me in the past, to come up with a fairly unique capture of Yosemite’s most frequently photographed monoliths.

Watch your step

Posted on February 24, 2012

Trouble brewing

I have many “favorite” photo locations in Yosemite Valley–some, like Tunnel View, are known to all; others, like this location along the Merced River, aren’t exactly secrets, but they’re far enough off the beaten path to be overlooked by the vacationing masses. While I used to count on being alone here, as often as not lately I share this shoreline with other photographers. While it’s nice to have a location to myself (so far I can still find a few of those spots in Yosemite Valley), I’m usually happy to share prime photographic real estate with a kindred spirit.

But. In recent years I’ve noticed more photographers abusing nature in ways that at best betrays their ignorance, and at worst reveals their indifference to the fragility of the very subjects that inspire them to click their shutters in the first place. Of course it’s impossible to have zero impact on the natural world: Starting from the time we leave home we consume energy that directly or indirectly pollutes the atmosphere and contributes greenhouse gases. Once we arrive at our destination, every footfall alters the world in ways ranging from subtle to dramatic–not only do our shoes crush rocks, plants, and small creatures, our noise clashes with the natural sounds that comfort humans and communicate to animals, and our vehicles and clothing scatter microscopic, non-indiginous flora and fauna.

For example

A certain amount of damage is an unavoidable consequence of keeping the natural world accessible to all who would like to appreciate it, a tightrope our National Park Service does an excellent job navigating. It’s even easy to believe that we’re not the problem–I mean, who’d have thought merely walking on “dirt” could impact the ecosystem for tens or hundreds of years? But before straying off the trail for that unique perspective of Delicate Arch, check out this admonition from Arches National Park.

Hawaii’s black sand beaches may appear unique and enduring, but the next time you consider scooping a sample to share with friends back on the mainland, know that Hawaii’s black sand is a finite, ephemeral phenomenon that will be replaced with “conventional” white sand as soon as its volcanic source is tapped–as evidenced by the direct correlation between the islands with the most black sands beaches and the islands with the most recent volcanic activity.

While Yosemite’s durable granite may lull photographers into environmental complacency, its meadows and wetlands are quite fragile, hosting many plants and insects that are an integral part of the natural balance that makes Yosemite unique. Not only that, they’re also home to, and nesting places of, native mammals, birds, and reptiles that so many enjoy photographing. Despite all this, I can’t tell you how often I see people in Yosemite (photographers in particular) unnecessarily trampling meadows, either to get in position for a shot or as a shortcut.

Don’t be this person

Still not convinced? If I can’t appeal to your environmental conscience, consider that simply wandering about with a camera and/or tripod labels you, “Photographer.” In that role you represent the entire photography community: when you do harm as Photographer, most observers (the general public and decision makers) go no farther than applying the Photographer label and lumping all of us into the same offending group.

Like it or not, one photographer’s indiscretion affects the way every photographer is perceived, and potentially brings about restrictions that directly or indirectly impact all of us. If you like fences, permits, and rules, just keep going wherever you want to go, whenever you want to go there.

It’s not that difficult

Environmental responsibility doesn’t require joining Greenpeace or dropping off the grid (not that there’s anything wrong with that). Simply taking a few minutes to understand natural concerns specific to whatever area you visit is a good place to start. Most public lands have websites with information they’d love you to read before visiting. And most park officials are more than happy to share literature on the topic (you might in fact find useful information right there in that stack of papers you jammed into the center console as you drove away from the entrance station).

When you’re in the field, think before advancing. Train yourself to anticipate each future step with the understanding of its impact–believe it or not, this isn’t a particularly difficult habit to form. Whenever you see trash, please pick it up even if it isn’t yours. And don’t be shy about reminding other photographers whose actions risk soiling the reputation for all of us.

DEVELOP A “LEAVE NO TRACE” MINDSET

A few years ago, as a condition of my Death Valley workshop permit, I was guided to The Center for Outdoor Ethics and their “Leave No Trace” initiative. There’s great information here–much of it is just plain common sense, but I guarantee you’ll learn things too.

Now go out and enjoy nature–and please save it for the rest of us.

======================================

A few words about this image

I captured this image while guiding a customer on a private workshop the day before last week’s Yosemite winter workshop. After months of clear skies, the sun rose on two inches of fresh snow in Yosemite Valley. As I did two days later when my workshop group was greeted with another dose of overnight snow, I shifted into hurry-up mode to get to as many spots as possible in the couple of hours we had before the snow would be gone–once the sun hits the trees, the snow disappears like magic.

After watching the storm clear from Tunnel View, we arrived here just in time to watch the day’s first light descend the surrounding granite walls. Our timing was ideal, as reflections are never better than when the reflective subject is in sun and the reflective surface in shade.

Shooting on a tripod (always!) enabled me to be at my camera’s ideal ISO 100 and select the f-stop the scene called for, without worrying about the resulting shutter speed. In this case I opted for a wide composition to include all of El Capitan and its reflection, which gave me lots of depth of field. Since the focus point for a reflection is the focus point of the reflective subject, not the reflective surface (that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t focus on the reflection, it just means you should take care not to focus on something floating on or resting beneath the reflection), at 20mm everything in my frame was at infinity. With depth of field not a concern, I dialed in f11, my lens’s sharpest f-stop (lenses tend to be sharper in their middle f-stops). F11 brought the added benefit of reducing image-softening diffraction that happens at smaller f-stops–I’ll go smaller than f11 only when the composition calls for it (or if I forget to change it from a previous shot).

The dynamic range (the range of light from darkest shadow to brightest highlight) was too much for my camera to handle, but a two-stop hard-transition graduated neutral density filter subdued the brilliant sunlight, enabling enough exposure to reveal detail in the foreground shadows. Hiding the GND transition in the linear band of shoreline trees was easy, and simple dodging and burning in Photoshop brought out shadow detail and ensured that the sunlit El Capitan was brighter than its reflection (as it should be). Also in Photoshop I applied a light touch with Topaz noise reduction, desaturated the sky slightly to prevent it from overpowering the scene, and did selective sharpening (selecting only the areas containing detail).

(While I do take my groups to this quiet spot beside the Merced River, the fragile riverside setting that requires crossing a small meadow makes me reluctant to share it with the general public.)

Horsetail Fall: Yosemite’s natural firefall

Posted on February 19, 2012

* * * *

This is the story of my 2012 Yosemite Winter workshop Horsetail Fall shoot. For more about when, where, and how to photograph Horsetail, read my Horsetail Fall Photo Tips article.

I returned home late last night from my annual Yosemite winter workshop. I’m happy to report that weeks of snow-dances, incantation, prayer, and just plain crossed fingers seem to have done the trick, as Yosemite Valley’s winter-long dry spell ended with two doses of snow last week. Since the most beautiful place on Earth is never more beautiful than when it’s blanketed in fresh snow, that was definitely the highlight of the week, but it was also fun to share the Horsetail Fall phenomenon with my group.

For those who don’t know what I’m talking about, for eleven+ months Horsetail Fall is probably Yosemite’s most anonymous waterfall. Even at its best, this ephemeral cataract is barely visible as a thin white thread descending El Capitan’s east flank–we can be standing directly beneath it and I still have to guide my students’ eyes to it (“See that tall tree there? Follow it all the way to the top of El Capitan; now run your eye to the left until you get to the first tree….”). But for about two and a half weeks in February, the possibility that a fortuitous confluence of snowmelt, shadow, and sunset light might, for a few minutes, turn this unassuming trickle into a molten red stripe, draws photographers like cats to a can-opener.

The curtain rises more than an hour before sunset, when a vertical shadow begins its eastward march across El Capitan’s south-facing flank. As the shadow advances the sunlight warms; as the unseen sun reaches the horizon, the only part of El Capitan not in shadow is Horsetail Fall; for a few minutes when the stars align–water in the fall, no clouds blocking the sun’s path to El Capitan, and enough haze to scatter all but the sun’s red rays–the fall is bathed in a red glow that resembles flowing lava. (Some people mistakenly call the Horsetail spectacle the “Firefall,” but that altogether different but no less breathtaking, manmade Yosemite phenomenon was suspended by the National Park Service in 1968.)

Some years Horsetail delivers sunset after sunset; other years bring daily of frustration. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to predict when all the tumblers will click into place: For every tale of a seemingly perfect evening when the sunset light was doused by an unseen cloud on the western horizon mere seconds before showtime, there’s another story about a cloudy evening when the setting sun somehow found a gap just as tripods were being collapsed. I know photographers who nailed Horsetail on their first attempt, and others who have been chasing it for years.

It’s fun to circle Yosemite Valley on pretty much any mid- to late-February afternoon, just to watch the hordes of single-minded photographers setting up camp like baby-boomers queueing for Stones tickets, securing a vantage point to capture (fingers crossed) their version of Horsetail Fall’s sunset pyrotechnics. When I lead a group it’s a always a tough call whether to sacrifice a nice Yosemite sunset at a more reliable location, or go all-in for the fickle grand prize. Generally, when February skies are cloudless, I might take my groups to the Horsetail circus multiple evenings (until we get it), because that’s what most are there for.

This year (2012) we had fresh snow and great clouds on Tuesday and Wednesday, so I targeted Thursday evening for Horsetail. Because we detoured to photograph the daily rainbow on Bridalveil Fall, I was resigned to dropping my group off, parking down the road, and walking back to the El Capitan picnic area beneath the fall (the spot best suited to large groups). But I was pleasantly surprised to find the necessary three parking spaces still available not much more than an hour before sunset. After a brief orientation (that started with helping everyone locate the fall), we all set up in fairly close proximity, practiced compositions and exposure, and shadow-watched. I’ve reached the point where I spend as much time watching the photographers as I do watching El Capitan–Horsetail Fall in February really has become an Event, not unlike waiting for the next act on the lawn at a concert.

Flow in the fall this year was low (it was bone-dry when I arrived Sunday), even by Horsetail standards, but still enough to make a photograph. We all held our breath, pleaded, and cheered as the shadow approached the fall. Shortly before sunset the amber light acquired a distinct pink hue and the chat, laughter, and cajoling died quickly in favor of clicking shutters. Instead of intensifying to the hoped-for red, the pink held for a few minutes before fading. So while we didn’t hit a home run, I think this year’s group still managed a stand-up triple.

I haven’t had a chance to get to this year’s images, so I’m posting a (better) 2008 Horsetail capture from a different spot. Despite appearances to the contrary, I didn’t have to scale shear granite to achieve this vantage point–I was in fact securely planted on the valley floor, shivering atop a snowbank beside the Merced River. Also of note is that this image was captured on February 9, earlier than many people claim the angle is right. I actually got it like this on consecutive nights that year, leading two different groups.

The definition of breathtaking

Posted on February 11, 2012

Death Valley is notorious for blue skies–great for tourists, but a scourge for photographers. Clouds add interest to a scene, and filtering harsh sunlight through clouds reduces contrast to a range a camera can capture. To mitigate harsh sky problems, I schedule my annual Death Valley workshop for winter to maximize the chance for clouds. And hedging my bets further, I time each workshop to coincide with a full moon–that way, if we don’t get clouds, careful location planning allows me to include a full moon in many of our sunrise and sunset shoots, and allows us to photograph Death Valley’s stark beauty by moonlight.

I returned last night from my 2012 workshop. Not only did we have a creative, enthusiastic group, we also were blessed with a wonderful blend of conditions. On our first two days we were treated to lots of clouds (and even a few snow flurries during a sunset shoot at Aguereberry Point) and beautiful sunrise color on the dunes. But by day three the Death Valley sky was back to business as usual and it was time to plug in a moonlight shoot.

I usually opt for moonlight on the Mesquite Flat Dunes near Stovepipe Wells, but during a pre-workshop visit to Badwater it occurred to me that the salt flat’s white surface was tailor made for the light of a full moon. Since the sky didn’t clear until our third day (the moon rises later every day), I was concerned that the moonlight wouldn’t reach Badwater, 282 feet below sea level and in the shadow of 5,700 foot Dante’s Peak, early enough. I briefly considered returning to the more exposed dunes, but finally decided that I could make Badwater work by simply leading the group out onto the salt flat until we reached the moonlight.

Sure enough, we arrived at Badwater a little after 8:00 p.m. to find ourselves in deep moonshadow. But across the valley, Telescope Peak and Badwater’s west fringe already basked in the light of the rising moon. So off we went to meet the advancing moonlight, following our headlamps through the darkness for about a half mile before reaching the advancing moonlight. With headlamps doused we paused in silence to take in our surroundings: Venus was just disappearing behind Telescope Peak and Jupiter sparkled high overhead; Orion and Sirius decorated the southern sky, while Cassiopeia and the Big Dipper straddled Polaris to the north. And rising above the mountains to the east, the moon painted the playa’s jigsaw surface with its silvery glow. Overuse has reduced “breathtaking” to cliché status, but I can’t help think it’s these moments the adjective was intended for.

After sharing exposure settings, a quick refresher on focus in moonlight, and some composition suggestions, I let the group get to work. We found compositions in all directions except due east, where the moon was simply too bright to include in the frame. With everyone working within a 100 foot radius, it was easy (and gratifying) to hear exclamations of delight as images popped onto LCD screens.

So amazing was the experience that we stayed far later than I’d planned. If I’d have been there by myself I’d have probably stayed out much longer, but I wanted to make sure no one was too tired for the sunrise moonset I had planned (also at Badwater) the following morning. The above image of the Big Dipper was captured toward the end of our shoot, when the entire playa was illuminated, but the moonlight hadn’t quite reached the Black Mountains. I used ISO 800, f5.6, and 30 seconds.

My 2013 Death Valley Winter Moon photo workshop is January 25-29–it’s already nearly full.

Color in nature

Posted on February 3, 2012

On consecutive nights last week the post-sunset sky featured a conjunction between the waxing crescent moon and Venus. This event had been on my calendar for a while, so when the first date arrived I was a little concerned to see thin clouds assembling in the west. Nevertheless, my camera and I headed to the foothills south and east of home, hoping to catch the celestial show above silhouetted oaks.

While the moon was too thin to penetrate the clouds that evening, the crimson sunset made my drive absolutely worthwhile. Here I used my 100-400 lens to isolate a hilltop oak (it shares this perch with a mate just out of the frame to the left) against the sunset. To hold the color and ensure that the tree and hillside remained in silhouette (totally black), I spot-metered the sky and set my exposure to +2/3 (above a middle tone).

In contrast to my previous post (a dawn moonset on the Big Sur coast), this image required virtually no processing. While I may have spent close to an hour preparing the Big Sur moonset image, this oak tree at sunset probably required less than five minutes from opening the raw file to saving a completed version, ready for output–and the bulk of that time was (tedious) cloning to remove sensor dust. No layers, no levels, curves, or saturation adjustments, no dodging and burning–nothing. But I know what you’re thinking: How do you get color like that without processing? I thought you’d never ask.

I’m convinced people forget how vivid color is in nature. How else to explain the skeptical looks and cynical questions when I post an image like this? To these people my brain thinks, “You don’t get outside enough,” but my mouth politely suggest that soon, very soon (tonight?), they install themselves on a vantage point with a good view of the western horizon about 30 minutes before sunset, and not take their eyes off the horizon until at least 30 minutes after sunset. No camera allowed. Just focus on the color, and I don’t think you’ll ever doubt sunset color again.

Does this mean that nobody exaggerates color in Photoshop? Of course not. I love color, and actively look for it when I shoot, and do certain things at capture to ensure that I get it. But I’m pretty sensitive to the difference between natural and manufactured (manipulated, enhanced, or whatever you want to call it) color. I find manufactured color is usually incongruous with the rest of the scene. For example, I’ve noticed that many HDR images often have an impossible combination of vivid reds and greens.

One of the most common causes of “lost” color is overexposure–not necessarily blown highlights, but hues washed out by sunlight. Left to its own devices, your camera’s meter might attempt to extract some detail from the hillside and tree, which of course would add exposure to the entire scene and dilute the red in the sky. Which is exactly why I never let my camera make decisions for me.

Digital photography the old fashioned way

Posted on January 29, 2012

Photoshop processing sometimes gets a bad rap. There’s nothing inherently pure about a jpeg file, and because a jpeg is processed by the camera, it’s actually less pure than a raw file. As a general rule, the less processing an image needs, the better, but sometimes raw capture followed by Lightroom/Photoshop processing is the only way to a successful image.

I’ve always considered myself a film shooter with a digital camera. But that doesn’t mean that I’m opposed to processing an image—in fact, processing is an essential part of every image. But just as Ansel Adams visualized the finished print long before he clicked the shutter, success today requires understanding before capture a scene’s potential, and the steps necessary to extract it later Lightroom/Photoshop.

For example

A couple of weeks ago, while co-leading Don Smith’s Big Sur photo workshop, our group had an early morning shoot that was equal parts difficult and glorious. The plan was a Garrapata Beach sunrise featuring the moon, one day past full, dropping into the Pacific at sunrise. But high tide and violent surf banished us to about 500 square feet of sheltered sand, and the cliffs above the beach (it’s bad for business when workshop participants get swept out to sea). Compounding the difficulty, the most striking aspect of the scene, a nearly full moon, was too bright for the rest of the scene. But despite the morning’s difficulties, I set to work trying to make an image because, well, that’s what photographers do.

As much as I wanted to be on the sand, aligning the moon with the the best foreground from down there would have made me a sitting duck for the waves. So I made my way along the cliff to an off-trail spot above a group of surf-swept rocks. It turns out the higher perspective was perfect for emphasizing the reflected moonlight that stretched all the way to the horizon.

With long exposures on a tripod, photographing the moonlight and beach wasn’t a problem. But adding the daylight-bright moon burning through the pre-dawn darkness made capturing the entire range of light in a single frame (a personal requirement) difficult, and perhaps impossible. Nevertheless, I spot-metered on the moon to determine the maximum exposure that would retain the ability to recover overexposed lunar detail later in the Lightroom raw processor. But even after maximizing the moon’s exposure, I didn’t have nearly enough light for the rest of the scene without first darkening the sky further using five stops of graduated neutral density (stacking my Singh-Ray three-stop reverse and two-stop hard GND filters). So far so good.

Satisfied that I could make the exposure work, but with very little margin for error, my next concern was finding a shutter speed that allowed enough light without risking motion blur in the moon. Because I needed sharpness throughout the frame, from the beach right below me all the way out to the moon, I couldn’t open all my aperture all the way. Whipping out my DOF app, I computed that focusing twenty feet away at f8 would give me sharpness from ten feet to infinity. Bumping to ISO 400 at f8 brought my shutter speed to four seconds, a value I was confident would freeze the moon enough. I clicked several frames to get a variety of wave effects, ultimately choosing this one for the implicit motion in foreground wave’s gentle arc.

In Lightroom, I cooled the light temperature slightly to restore the night-like feel. Using five GND stops at capture required significant Photoshop brightening of the sky to return it to a reasonable range. A few years ago this would have introduced far too much noise, but the latest noise reduction software (I use Topaz) is amazing. As expected, even after all my exposure and processing machinations, I still needed to process the raw file a second time to recover the highlights in the moon. Because the two versions were the same capture, combining them in Photoshop was a piece of cake.

A Gallery of Favorite Seascapes

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh your screen to reorder the display.

Alpenglow: Nature’s paintbrush

Posted on January 24, 2012

Red Dawn, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

168 mm

.8 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

The foreground for Mt. Whitney is the rugged Alabama Hills, a disorganized jumble of rounded granite boulders, familiar to many as the setting for hundreds of movies, TV shows, and commercials. These weathered rocks make wonderful subjects without the looming east face of the southern Sierra. What makes this scene particularly special is the fortuitous convergence of topography and light that rewards early risers with a skyline dipped in pink–add a few clouds and it’s a photography trifecta.

We’ve all seen the pink band above the horizon opposite the sun shortly before sunrise or after sunset. Sometimes called “the belt of Venus,” this glow happens because sunlight that skims the Earth’s surface just before sunrise (or shortly after sunset) has to battle its way through the thickest part of the atmosphere, which scatters the shorter wavelengths (those toward the blue end of the visible spectrum), leaving just the longer, red wavelengths capping the horizon. When mountains jut high enough to reach into this region of pink light, we get “alpenglow.” Towering above the terrain to the east, the precipitous Sierra crest, anchored by 14,500 foot Mt. Whitney (the highest point in the contiguous 48 states) and 13,000 foot Lone Pine Peak, is ideally located to receive this sunrise treatment.

The image above was captured on a frigid January morning. While the best light on the Sierra crest usually starts a couple of minutes before the “official” (flat horizon) sunrise, this morning Mt. Whitney hid behind the clouds until the alpenglow was well underway. Like a piece of art waiting for its spotlight, the cloudy shroud was pulled back just as the sunlight struck Mt. Whitney, and for a couple of minutes it appeared as if a giant paintbrush had dabbed the swirling canvas with pink.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A Mt. Whitney Gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Trust your instincts

Posted on January 20, 2012

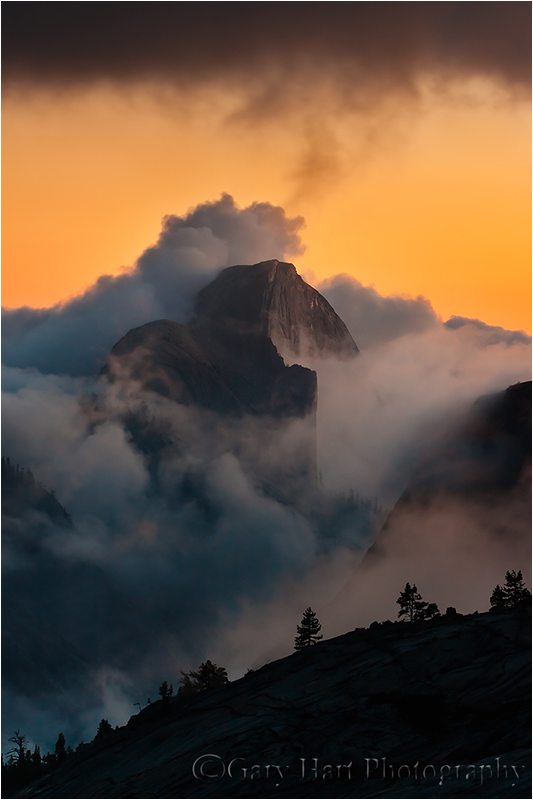

Emergence, Half Dome from Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

70-200L F4

3.2 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

This week I’ve spent some time going through past images that I just haven’t had time to get to. Unlike many of the images I uncover by returning to old shoots, this one from the final night of my October 2010 Eastern Sierra workshop wasn’t a surprise–the sky over Half Dome that night was magic, something I’ll never forget. Shortly after returning home I selected and processed one, but in conditions like that I always shoot enough variety of compositions that I knew there must be more there. While I have a general rule to only select one image of any scene from a single shoot, this is a perfect example of why I refuse to be bound by rules.

From the Clouds, Half Dome from Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

24-105L F4

5 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

Comparing the two images from that night, what strikes me most isn’t the similarity, but the differences. Despite being captured less than a minute apart, they illustrate creative choices that underscore a point I keep hammering on: Photographers are under no obligation to reproduce human “reality” (because it can’t be done). Because photographic reality is an impossible moving target, my obligation as a photographer is to my camera’s reality. And if I do things right, I can use my camera’s reality to transcend visual reality and convey some of the emotion of the moment.

So, in the “Emergence” (tight vertical) composition, I chose to emphasize Half Dome’s power and nothing else. I centered Half Dome and exposed for its granite face, letting the swirling clouds darken and the foreground go completely black. The dark clouds above Half Dome cap the top of the scene–there’s really nowhere else for your eye to go than Half Dome.

Today’s “From the Clouds” composition is more about the moment’s grandeur. I widened the perspective considerably and brightened my exposure enough to encourage your eye to wander about the frame a bit. There’s no question as to where your eye will end up, it just takes a little longer to get there. In other words, expanding the perspective and providing more light invites you to leave and return to Half Dome at your leisure.

Did I consciously plot this that night? Nope. Honestly, I’m rarely this analytical when I shoot–I just don’t want my left (logical) brain to distract my right (creative) brain. But I do believe that if you cultivate (and trust!) your intuition, creative decisions like this will happen organically. (But learn metering and exposure until it becomes automatic!)

So while I had no conscious thought of how to control your experience of this scene, I’ve done this long enough to know that these creative choices don’t just happen by accident. Without getting into the divine intervention claims trumpeted by some photographers (label it what you will), I believe everyone can access untapped creative potential that takes them far beyond what can be accomplished with the conscious mind. And it starts with trust.

BTW—I prefer the first one (Emergence).