Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Under the Influence

Posted on February 20, 2018

Happy Birthday, Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams’ influence on photography is impossible to measure. Not only Adams’ influence on photographers, but his influence on the viewers of photography as well. Ask 100 people to name a photographer and 99 will name Ansel Adams; ask them to name a second photographer and you’ll get 99 different names.

Through his use of relationships, perspective, and tones, Adams’ images masterfully emphasized light and shape to guide viewers’ eyes and emphasize aspects of his scenes that he found most compelling. An entire generation’s relationship with nature was unconsciously shaped by the prints of Ansel Adams, not because they showed the world as we already knew it, but because they showed us the world in new and exciting ways.

Now that I’m a photographer, Adams’ influence manifests most in the freedom to render the natural world as my camera sees it, liberating me from the impossible task of duplicating human vision. The camera and the eye experience the world differently; rather than fight that difference, Adams’ photography celebrated it.

Today’s photographers perpetuate Adams’ vision with the help of far more advanced tools, tools so advanced that it’s easy to overlook the foundation he laid for us. On blogs and forums I see some rolling their online eyes at all the Ansel Adams adulation, discounting his influence and labeling his photography pedestrian and prosaic when compared to current efforts: “What’s the big deal?” they say. To those dubious photographers I respond, criticizing Ansel Adams’ by comparing his monochrome masterpieces to the striking, vivid, blended, and stitched images captured today is like criticizing Lewis and Clark for toiling more than two years on a route that can now be traveled in a few days.

About this image

Last week’s Yosemite Horsetail Fall workshop wrapped up at one of my favorite spots in Yosemite Valley, a spot I’ve photographed so many times that it’s an enjoyable challenge to find something unique. The light on Half Dome that evening was beautiful, but nothing I hadn’t seen before. Rather than settle for the beautiful but conventional shots of Half Dome and its reflection, I scanned the scene for quality light elsewhere.

It wasn’t long before my gaze landed on a small stand of deciduous trees, stripped bare by winter cold, basking in the warm rays of the day’s last sunlight. As I pondered the scene, a rogue beam slipped through to illuminate the crown of a single evergreen, punctuating the otherwise monochrome scene with a splash of color.

Though my eyes could see a confusion of textured granite and tangled branches in the dark background shadows, I knew that detail would be nothing but a distraction in an image. But as Ansel Adams so magnificently demonstrated, an image’s full potential isn’t realized unless the finished product, and the processing required to get there, is visualized and executed at capture.

Well aware of late afternoon light’s ephemeral nature, I quickly mounted my Sony 100-400 GM lens to my tripod, attached my camera, and framed my composition. Taking advantage of the camera’s limited dynamic range (when compared to human vision), I gave the scene just enough light to reveal the sunlit trees. Given my a7RIII’s extreme dynamic range, I knew I could pull detail from the shadows in Photoshop if I wanted to, but in this case I went the other way. Processing the image in Lightroom on my computer, I enhanced the contrast, banishing the distracting background to virtually black shadows, leaving only the shape and light that drew my eye in the first place.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

Influenced by Ansel Adams

Category: Ansel Adams, Sony 100-400 GM, Sony a7R III, winter, Yosemite Tagged: Ansel Adams, nature photography, winter, Yosemite

Aspen abstract

Posted on February 25, 2017

I recently started rereading Ansel Adams’ “Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs,” a book I’d recommend to anyone interested in the thinking side of photography. Though much of the book covers equipment and techniques that are irrelevant to today’s digital photographer, Adams’ words reveal a vision and mastery of craft that transcends technology. Like him or not (I do!), you can’t deny that Ansel Adams possessed an artist’s vision and an ability to convey that vision in ways the world had never seen.

©Ansel Adams

Aspen, New Mexico, 1958

“The majority of the viewers (of this image) think it was a sunlit scene. When I explain that it was diffused lighting from the sky and also reflected light from distant clouds, some rejoin, ‘Then why does it look the way it does?’ Such questions remind me that many viewers expect a photograph to be a literal simulation of reality.”

Ansel Adams in “Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs”

Another takeaway from the book is Adams’ clear disdain for pictorialism, a more abstract approach to photography that (among other things) uses the camera’s unique vision to interpret the world in ways that are vastly and intentionally different from the human experience. Preferring instead the more literal front-to-back sharpness of the f/64 group that became his hallmark, Adams had little room for pictorialists’ soft focus and abstract images.

I, on the other hand, love using limited depth of field to emphasize my primary subject and disguise potential distractions. When we explore the world in person, our ability to pivot our head, move closer or farther, and change perspective allows us to enables us to lock in on a compelling subject and experience the scene in the way we find most meaningful. But an image is a constrained, two-dimensional approximation of the real world as seen by someone else. The photographer shares his or her experience of the scene by guiding our eyes with visual clues about what’s important and how to find it.

This reality wasn’t lost on Ansel Adams. Despite his distaste for soft focus techniques, Adams guided viewers of his images with in other ways, particularly his use of light. He knew that the camera and human eye handle light differently, and used every trick at his disposal, both at capture and in the darkroom, to leverage that difference.

At the risk of initiating a debate about the relative merits of the two techniques, I’ll just say that I’m a fan of both and am not afraid to apply whichever approach best suits my objective. And I suspect that if Ansel Adams were photographing today, he would be taking full advantage of the creative possibilities created by today’s technology.

Last October I was exploring the aspen grove at the end of the Lundy Canyon road near Mono Lake. With fall color peaking I put extension tubes on my Sony 70-200 f/4 looking for subjects that I could get close to, but with a distant enough background to maximize focus contrast (sharp/soft). I’ve always felt that soft focus aspen make a great background, but they need to be soft enough that individual leaves and trunk detail don’t distract.

I started looking for dangling leaves, either individual or bunches, but soon turned my attention to stark white aspen trunks that stood out in striking contrast against the distant wall of yellow leaves. I soon zeroed in on this trunk for its well-spaced knots, gentle curve, and clean, textured bark, plus the nice assortment of parallel trunks at varying distances in the background.

This frame I shot wide open at the closest possible focus distance to get the softest background focus. To emphasize the white trunks, I exposed the scene as bright as I could without clipping the highlights in the primary trunk. On my camera’s LCD at capture this image looked pretty much as you see it here, and required minimal processing.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Selective Focus Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: aspen, Eastern Sierra, extension tubes, Lundy Canyon, Sony 70-200 f4, Sony a7R II Tagged: Ansel Adams, aspen, autumn, Eastern Sierra, fall color, nature photography

Roll over Ansel

Posted on August 25, 2014

A few days ago I was thumbing through an old issue of “Outdoor Photographer” magazine and came across an article on Lightroom processing. It started with the words:

“Being able to affect one part of the image compared to another, such as balancing the brightness of a photograph so the scene looks more like the way we saw it rather than being restricted by the artificial limitations of the camera and film is the major reason why photographers like Ansel Adams and LIFE photographer W. Eugene Smith spent so much time in the darkroom.” (The underscores are mine.) Wow, this statement is so far off base that I hardly know where to begin. But because I imagine the perpetuation of this myth must send Ansel Adams rolling over in his grave, I’ll start by quoting the Master himself:

- “When I’m ready to make a photograph, I think I quite obviously see in my minds eye something that is not literally there in the true meaning of the word.”

- “Photography is more than a medium for factual communication of ideas. It is a creative art.”

- “Dodging and burning are steps to take care of mistakes God made in establishing tonal relationships!”

Do those sound like the thoughts of someone lamenting the camera’s “artificial limitations” and its inability to duplicate the world the “way we saw it”? Take a look at just a few of Ansel Adams’ images and ask yourself how many duplicate the world as we see it: nearly black skies, exaggerated shadows and/or highlights, and skewed perspectives. And no color! (Not to mention the fact that an image is a two-dimensional approximation of a three-dimensional world.) Ansel Adams wasn’t trying to replicate scenes more like he saw them, he was trying to use his camera’s unique (not “artificial”) vision to show us aspects of the world we miss or fail to appreciate.

You’ve heard me say this before

The rest of the OP article contained solid, practical information for anyone wanting to come closer to replicating Ansel Adams’ traditional darkroom techniques in the contemporary digital darkroom. But it’s the perpetuation of the idea that photographers are obligated to photograph the world like they saw it that continues to baffle me.

The camera’s vision isn’t artificial, it’s different. To try to force images to be more human-like is to deny the camera’s ability to expand viewers’ perception of the world. Limited dynamic range allows us to emphasize shapes that get lost in the clutter of human vision; a narrow range of focus can guide the eye and draw attention to particular elements of interest and away from distractions; the ability to accumulate light in a single frame exposes color and detail hidden by darkness, and conveys motion in a static medium.

No, this isn’t the way it looked when I was there

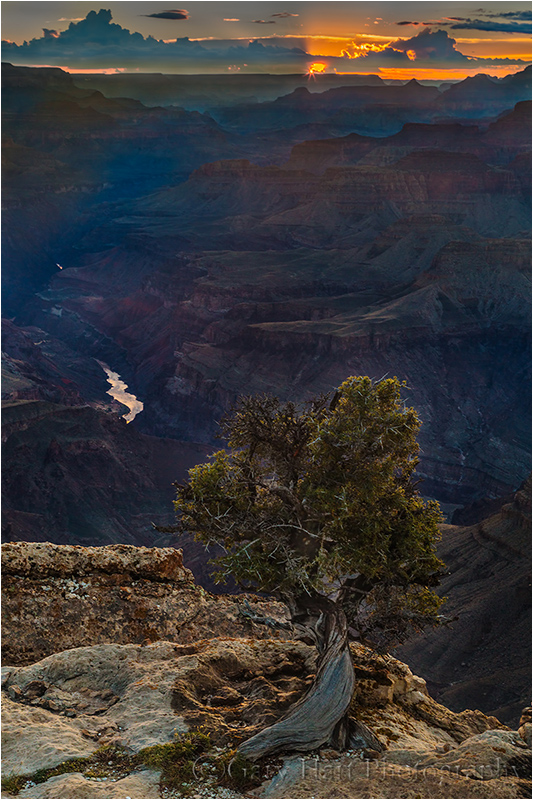

While this sunset scene from Lipan Point at the Grand Canyon is more literal than many of my images, it’s not what my eyes saw. To emphasize the solitude of the lone tree, I allowed the shaded canyon to go darker than my eyes saw it. This was possible because a camera couldn’t capture enough light to reveal the shadows without completely obliterating the bright sky (rather than blending multiple images, I stacked Singh-Ray three- and two-stop hard transition graduated neutral density filters to subdue the bright sky).

To convey a mood more consistent with the feeling of precarious isolation of this weather-worn tree, I exposed the scene a little darker than my experience of the moment. The sunstar, which isn’t seen by the human eye but was indeed my camera/lens’ “reality” (given the settings I chose), was another creative choice. Not only does it introduce a ray of hope to an otherwise brooding scene, without the sunstar the top half of the scene would have been too bland for me to include as much of the shadowed canyon as I wanted to.

I’m not trying to pass this image off as a masterpiece (nor am I comparing myself to Ansel Adams), I’m simply trying to illustrate the importance of deviating from human reality when the goal is an evocative, artistic image. Much as music sets the mood in a movie without being an actual part of the scene, a photographer’s handling of light, focus, and other qualities that deviate from human vision play a significant role in the image’s impact.

A Gallery of My Camera’s World

(Stuff my camera saw that I didn’t)

Category: Grand Canyon, Lipan Point Tagged: Ansel Adams, Grand Canyon, Lipan Point, Photography, sunset, sunstar

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About