Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Photographic reality: The missing dimension

Posted on June 4, 2012

“Photography’s gift isn’t the ability to reproduce reality, it’s the ability to expand it.”

(The sixth and final installment of my series on photographic reality.)

So far I’ve written about focus, dynamic range, confining borders, motion, and time, but I think most obvious (and also I’m afraid most overlooked) difference separating the camera’s vision from our own is the missing dimension: depth.

Photography attempts to render a three dimensional world in a two dimensional medium—the most photographers can hope for is the illusion of depth. While anyone can put a camera to their eye and compose the lateral, left-to-right aspect of a scene, translating their own three-dimensional experience to their camera’s two-dimensional reality is a leap that many miss. This may explain why a sense of depth is often the most significant quality separating a merely good image from an outstanding image.

Achieving the illusion of depth starts with looking beyond your primary subject and finding a complementary foreground or background: If your primary subject is nearby, find a background object, shape, or color that frames, balances, and/or helps your subject stand out; conversely, if your primary subject is in the distance, look for foreground elements that can lead your viewers’ eyes through the frame without distracting or competing for attention.

Once you have your foreground/background elements worked out, your composition isn’t complete. In your three-dimensional view, size and distance are easily interpreted, something we stereographic humans take for granted. But your scene’s depth is lost to your camera. In a two-dimensional world aligned objects at varying distances loose the separation that makes them stand out—you need to visually separate these merged objects—put them on different lines of sight—to allow your viewer to imagine the depth you see at capture. I can’t emphasize how important this is.

In my many years of observing and assisting other photographers working to improve their images, I’ve decided that the single most significant factor holding them back is their ignorance of, or unwillingness to wield, their control over their images’ depth relationships. There seems to be an invisible force that binds tripods to their first landing place. Overcoming this force (to which I’m not immune) requires vigilant attention to each visual element in your frame and taking whatever steps necessary to ensure that each stands alone. If you can’t achieve separation from your current position, move! Simply repositioning a little left/right, up/down, forward/backward really can make a huge difference. In other words, in a static landscape, it’s your job to be dynamic.

For example

With the benefit of a 360 degree view, it was clear that all the elements were in place for a spectacular sunset atop Yosemite’s Sentinel Dome. An afternoon rain had scoured the air of color-robbing particles, and an opening on the west western horizon left a clear path for the setting sun to illuminate the clouds above Half Dome to the east. But as spectacular as I expected the color above Half Dome to be, I wasn’t going to be satisfied with just another pretty picture of Half Dome at sunset.

One of the things I like most about photographing from Sentinel Dome is the variety of foreground subjects: rocks, cracks, and of course the solitary jeffrey pine made famous by Ansel Adams and others, now dead and on its side. On this evening, guessing (hoping) that the earlier downpour had filled indentations I remembered on Sentinel’s southeast flank, I headed over there.

One thing I pride myself in is arriving at a location early, well before the best conditions, to allow time to anticipate the light and assemble the elements of my composition. Being such a deliberate shooter, this is really a necessity for me. So when I found these pools right where I’d hoped, I was able to take the time to figure out how to use them. I started by moving around quite a bit, first to find the angle that would best frame Half Dome with the pools, then forward and backward to get an idea of the best distance and focal length that would give Half Dome enough size while giving the pools enough room. A factor in these distance/focal-length considerations was finding the angle that would allow me to include a reflection of the clouds, which meant moving up and down as well. In this case I dropped quite low, probably no more than a foot off the ground, taking care not to get so low that the bottom of Half Dome merged with the edge of Sentinel Dome. With the composition worked out, I did some depth of field figuring and decided that I’d better stop all the way down to f20 to ensure a perfectly sharp foreground and acceptably sharp Half Dome.I focused on the granite about eight feet away and think I did a pretty good job achieving front-to-back sharpness. (Today I’d use the DOF app on my iPhone, but checking it now confirms that I did okay.)

Being on a tripod with no motion in the scene meant I was able to go with whatever shutter speed gave me the exposure I wanted, at my camera’s native ISO 100. I metered on the foreground and used a graduated neutral density filter to darken the bright sky, starting my exposures before the best color started (you never know when the color will peak—it’s best to have a few too many images than to realize after the fact that the color you’re waiting for isn’t coming), monitoring my histogram and adjusting down in 1/3 stop increments as the light dropped.

On this evening the color just kept getting better and better, until the air seemed to buzz with color and the entire landscape glowed red. Believe it or not, the red was even more vivid than what you see here, but I decided to tone down the saturation a bit because there comes a point where Mother Nature seems to defy credibility. This remains one of my favorite images.

Category: Half Dome, How-to, Sentinel Dome Tagged: depth of field, Half Dome, Photography, sunset, Yosemite

Photographic Reality: See the light

Posted on May 21, 2012

“Photography’s gift isn’t the ability to reproduce your reality, it’s the ability to expand it.”

(The third installment of my series on photographic reality.)

Dynamic range

One of photographers’ most frequent complaints is their camera’s limited “dynamic range,” it’s inability to capture the full range of light visible to the human eye. To understand photographic dynamic range, imagine light as water you’re trying to capture from a tap–if the human eye can handle a bucket-full of light, a camera will only capture a coffee cup. Any additional light reaching your sensor simply overflows, registering as pure white.

Limited dynamic range isn’t a problem when a scene is lit by omnidirectional, shadowless light. But while I can’t speak for other planets, here on Earth we’re illuminated by only one sun. Since most Earthlings prefer blue skies and brilliant, (unidirectional) sunshine that buries everything that’s not directly lit in dark shadows. Fortunately, human vision has evolved to the point where we can see detail in shadows and sunlight simultaneously.

Cameras haven’t evolved quite so far–on sunny days, photographers must choose between photographing what’s in the shade or what’s in direct sunlight. Exposing to capture detail in the shadows brings in so much light that everything in sunlight is overexposed; exposing to avoid overexposure of sunlit subjects doesn’t permit enough light to see what’s in the shadows.

Managing the light

Experienced photographers understand their camera’s limited dynamic range and take steps to mitigate it. For example, artificial light (such as a flash) can be used to fill shadows, or multiple exposures (covering a scene’s range of light) can be digitally blended into one image. But as a natural-light landscape photographer, I don’t even own a flash (really), and given that I only photograph scenes I can capture with a single exposure, I also never blend exposures.

The simplest solution for me is to avoid harsh, midday light. Full shade (absolutely no direct light) works, and a layer of clouds that spreads sunlight over the entire sky illuminates the landscape with even (low contrast), shadowless light that’s a joy to photograph. And the low, very early or very late light that occurs just after sunrise or before sunset has been subdued enough by its long journey through the thick atmosphere that the contrast falls into a camera’s manageable range. I’m also a huge advocate of graduated good old fashioned neutral density filters to reduce the difference between a bright sky and darker foreground.

Less is more

The best photography often results from subtraction. Photographers who merely take steps to make their camera’s world more like their own miss a great opportunity to show aspects of the world easily missed by the human experience. In the right hands, a camera’s limited light capturing ability can be used to emphasize special aspects of nature and eliminate distractions.

Exposing to hold the color in bright sky or water can eliminate unlit distractions and render shaded subjects in shape-emphasizing silhouette. And compositions that feature brightly backlit, translucent flowers and leaves explode with natural color that stands out against a shaded, black background.

Whether the image is a silhouetted mountain or translucent dogwood, the camera’s rendering is nothing like your experience of the scene. But it is a true rendering from the camera’s perspective, achieved without digital manipulation.

For example

Last week I rose at 4:00 a.m. to photograph a thin crescent moon rising above Half Dome almost an hour before sunrise. It was one of those, “I’m witnessing the most beautiful thing on Earth” moments, and I couldn’t believe no one else was there to enjoy it. I arrived about fifteen minutes before I expected the moon to rise, more than enough time to set up one tripod with my 1DS III 100-400 lens bulls-eyed on Half Dome at 400 mm. Another tripod had my 5D III and 24-105 composed to include El Capitan and Half Dome (above).

When the moon arrived I gave the scene just enough light to reveal the rich blue in the twilight sky. At that exposure the thin sliver of moon was completely overexposed (no lunar detail), a crescent of pure white that stands out boldly against the dark blue sky. A few stars pop through the darkness as well.

My eyes had adjusted to the predawn light enough for me to barely discern the trees and granite in Yosemite Valley below, and the rising sun had already started to wash out some of the sky’s color. But at the exposure I chose, my camera saw only Yosemite’s iconic skyline, El Capitan on the left and Half Dome on the right, as distinct black shapes against the cool blue sky. Rendering the image this way reduces erases the rocks and trees that add nothing to the scene, reducing this special Yosemite moment to its most compelling elements, color and shape.

Autumn Light, Yosemite: Here I metered on the brightest part of the backlit leaves, slightly underexposing to capture the leaves’ exquisite gold and turn the shaded background to complementary shades that range from dark green to nearly black. A small aperture softened dots of sky to small jewels of light.

Up next: Accumulate light

Category: El Capitan, Half Dome, Moon, Photography, stars, Yosemite Tagged: crescent moon, El Capitan, Half Dome, Photography, Yosemite

It’s personal

Posted on May 8, 2012

Some of my oldest, fondest Yosemite memories involve Glacier Point: Craning my neck from Camp Curry, waiting for the orange glow perched on Glacier Point’s fringe to grow into a 3,000 foot ribbon of fire; stretching on tiptoes to peer over the railing to see the toy cars and buildings in miniature Yosemite Valley; standing on the deck of the old Glacier Point Hotel my father’s breathless excitement at the sudden shimmering rainbow arcing across Half Dome’s face.

The National Park Service doused the Firefall in 1968 and my father died almost eight years ago. While El Capitan’s Horsetail Fall delivers a no less spectacular (albeit less reliable) February show across the valley, and my father’s rainbow image is a vivid reminder on my mom’s living room wall, those Glacier Point memories are irreplaceable.

Glacier Point closes with the first significant snow each fall, and doesn’t open until the snow melts in late spring–avoiding summer’s crowds and interminable blue skies means I don’t make it to Glacier Point much anymore. So I was thrilled to learn that this year’s dry winter enabled the NPS to open Glacier Point on April 20, early enough for me to share it with last week’s workshop group.

Because I already had plans for Mirror Lake, moonrise, and moonlight photography later in the workshop, I decided that the workshop’s first sunset was the best time time for the Glacier Point trip. Stopping first at Washburn Point just a short distance up the hill, we were treated to a harbinger of what was to come later–a mix of wave clouds and alto-cumulus above the Sierra crest to the east, and wonderfully warm light on Half Dome. Not knowing how long the light would last, I hustled the group to Glacier Point, arriving soon enough to get a front row seat for what turned out to be the best sunset experience I’ve ever had at Glacier Point.

The light held out all the way to sunset, warming from amber to pink and finally red, painting the sky and saturating the granite landscape with shades of magenta. As it turned out we had many other photogenic moments (dogwood, a moonbow, and the rise of the “super” moon above Yosemite Valley) in the workshop’s remaining three days, but this sunset on Glacier Point will be my fondest memory.

That’s Half Dome front and center, Cloud’s Rest behind it to the right, and Nevada (top) and Vernal Falls in the lower right.

Category: Half Dome, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: Glacier Point, Half Dome, Nevada Fall, Vernal Fall, Yosemite

Starry, starry night

Posted on March 14, 2012

Winter Star Trails, Half Dome and the Merced River, Yosemite

Canon 1Ds Mark III

28 mm

24 minutes

F/2.8

ISO 400

Yosemite is beautiful any time, under any conditions, but adding stars to the mix is almost unfair. I started doing night photography here on full moon nights about six or seven years ago, but recently I’ve enjoyed photographing the exquisite starscape of moonless Yosemite nights. With no moonlight to wash out the sky, the heavens come alive. Of course without moonlight visibility is extremely limited, and focus is sometimes an act of faith. But eyes adjust, and focus improves with experience (I promise).

After photographing, among other things, Yosemite Valley with a fresh blanket of snow and Horsetail Fall in all its illuminated splendor, last month’s Yosemite winter workshop had already been a success. Nevertheless, after dinner on our next to last night I took the group to this peaceful bend in the Merced River to photograph Half Dome beneath the stars.

I started with a high ISO test shot to get the exposure info for everyone, then converted to a long exposure that allowed me to ignore my camera for a half hour or so while I worked with the rest of the group. Helping with focus, composition, and exposure, I made sure everyone had had a success before suggesting we wrap up.

The fabulous photography is only part of what makes these night shoots memorable–they’re also just plain fun. That night we ended up staying out for about an hour, shooting, shivering, and laughing–lots of laughing. And as the group packed up, I returned to my camera and found this waiting for me.

Check out next year’s Yosemite winter workshop.

Trust your instincts

Posted on January 20, 2012

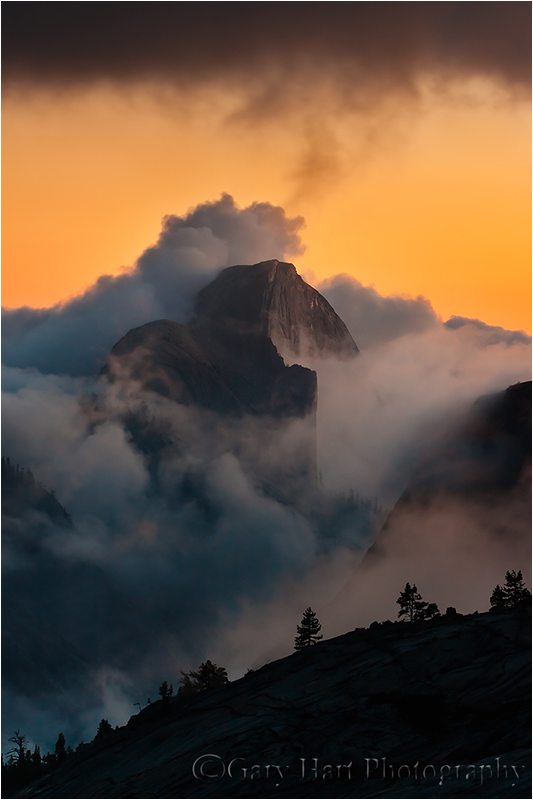

Emergence, Half Dome from Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

70-200L F4

3.2 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

This week I’ve spent some time going through past images that I just haven’t had time to get to. Unlike many of the images I uncover by returning to old shoots, this one from the final night of my October 2010 Eastern Sierra workshop wasn’t a surprise–the sky over Half Dome that night was magic, something I’ll never forget. Shortly after returning home I selected and processed one, but in conditions like that I always shoot enough variety of compositions that I knew there must be more there. While I have a general rule to only select one image of any scene from a single shoot, this is a perfect example of why I refuse to be bound by rules.

From the Clouds, Half Dome from Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

24-105L F4

5 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

Comparing the two images from that night, what strikes me most isn’t the similarity, but the differences. Despite being captured less than a minute apart, they illustrate creative choices that underscore a point I keep hammering on: Photographers are under no obligation to reproduce human “reality” (because it can’t be done). Because photographic reality is an impossible moving target, my obligation as a photographer is to my camera’s reality. And if I do things right, I can use my camera’s reality to transcend visual reality and convey some of the emotion of the moment.

So, in the “Emergence” (tight vertical) composition, I chose to emphasize Half Dome’s power and nothing else. I centered Half Dome and exposed for its granite face, letting the swirling clouds darken and the foreground go completely black. The dark clouds above Half Dome cap the top of the scene–there’s really nowhere else for your eye to go than Half Dome.

Today’s “From the Clouds” composition is more about the moment’s grandeur. I widened the perspective considerably and brightened my exposure enough to encourage your eye to wander about the frame a bit. There’s no question as to where your eye will end up, it just takes a little longer to get there. In other words, expanding the perspective and providing more light invites you to leave and return to Half Dome at your leisure.

Did I consciously plot this that night? Nope. Honestly, I’m rarely this analytical when I shoot–I just don’t want my left (logical) brain to distract my right (creative) brain. But I do believe that if you cultivate (and trust!) your intuition, creative decisions like this will happen organically. (But learn metering and exposure until it becomes automatic!)

So while I had no conscious thought of how to control your experience of this scene, I’ve done this long enough to know that these creative choices don’t just happen by accident. Without getting into the divine intervention claims trumpeted by some photographers (label it what you will), I believe everyone can access untapped creative potential that takes them far beyond what can be accomplished with the conscious mind. And it starts with trust.

BTW—I prefer the first one (Emergence).

Category: Half Dome, Olmsted Point, Photography Tagged: Half Dome, Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Magenta moonrise, Half Dome, Yosemite

Posted on November 21, 2011

With my camera I’m able to create my own version of any view, adjusting focal length (the amount of magnification) and composition to emphasize whatever elements and relationships I find most compelling. Today’s image was captured on the final shoot ofmy most recent fall workshop, three sunsets after my previous image, from virtually the same location.

On Sunday evening (the first sunset), with Yosemite Valley emerging from swirling clouds and the moon high above Leaning Tower, I chose a wide composition that encompassed the entire scene. Wednesday evening the eastern horizon was partially obscured by a uniform layer of translucent clouds. As the sunset progressed, we watched the moon’s glow rise through the throbbing pink clouds. When it slipped into a small opening I quickly tightened my composition to create a frame that was all about Half Dome and the moon. I made the Sunday moon a delicate accent, the Wednesday moon a bold exclamation point. These decisions remind me that photography is more than simply documenting a moment; it’s taking that moment and using the camera’s unique vision to convey its essence.

One more thing: By the last day of a workshop, relationships have been forged and inside jokes have blossomed. The group interaction feels more like a family gathering (minus the disfunction) than the assembly of diverse strangers we were three-and-a-half days earlier. On this evening in particular we had a great time laughing about things that anyone who hadn’t been in the workshop couldn’t appreciate. It was lots of fun, and a wonderful way for me to wrap up this year’s fall workshop season.

A landscape photographer’s time

Posted on June 25, 2011

On my run this morning I listened to an NPR “Talk of the Nation” podcast about time, and the arbitrary ways we Earthlings measure it. The guest’s thesis was that the hours, days, and years we measure and monitor so closely are an invention established (with increasing precision) by science and technology to serve society’s specific needs; the question posed to listeners was, “What is the most significant measure of time in your life?” Most listeners responded with anecdotes about bus schedules, school years, and work hours that revealed how our conventional time measurement tools, clocks and calendars, rule our existence. Listening on my iPhone, I wanted to stop and call to share my own relationship with time, but quickly remembered I wasn’t listening in realtime to the podcast. So I decided to blog my thoughts here instead.

Landscape photographers are governed by far more primitive constructs than the bustling majority, the fundamental laws of nature that inspire, but ultimately transcend, clocks and calendars: the Earth’s rotation on its axis, the Earth’s revolution about the Sun, and the Moon’s motion relative to the Earth and Sun. In other words, clocks and calendars have little to do with the picture taking aspect of my life; they’re useful only when I need to interact with the rest of the world on its terms (that is, run the business).

While my years are ruled by the changing angle of the Sun’s rays, and my days are inexorably tied to the Sun’s and Moon’s arrival, I can’t help fantasize about the ability to schedule my spring Yosemite moonbow workshops (that require a full moon) for the first weekend of each May, or mark my calendar for the blizzard that blankets Yosemite in white at 3:05 p.m. every February 22. But Nature, despite human attempts to manipulate and measure it, is its own boss. The best I can do is adjust my moonbow workshops to coincide with the May (or April) full moon each year; or monitor the weather forecast and bolt for Yosemite when a snowstorm is promised (then wait with my fingers crossed).

The insignificance of clocks and calendars is never more clear than the first morning following a time change. On the last Sunday of March, when “normal” people moan about rising an hour earlier, and the first Sunday of November, as others luxuriate in their extra hour of sleep, it’s business as usual for me. Each spring, thumbing its nose at Daylight Saving Time, the Sun rises a mere minute (or so) earlier than it did the day before; so do I. And each fall, on the first sunrise of Standard Time, I get to sleep an an entire minute longer. Yippee.

Honestly, I love nature’s mixture of precision and (apparent) randomness. I do my best to maximize my odds for something photographically special, but the understanding that “it” might not (probably won’t) happen only enhances the thrill when it, or maybe something unexpected and even better, does happen. The rainbow in today’s image was certainly not on anybody’s calendar; it was a fortuitous convergence of rain and sunlight (and ecstatic photographer). My human “schedule” that evening was a 6 p.m. get-to-know/plan-tomorrow dinner meeting with a private workshop customer. But seeing the potential for a rainbow, I suggested that we defer to Mother Nature, ignore our stomachs, and go sit in the rain. Fortunately he agreed, and we were amply rewarded for our inconvenience and discomfort.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Gallery of Rainbows

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, Photography, rainbow, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, El Captian, Half Dome, nature photography, Photography, Rainbow, Yosemite

The Other Ninety-Nine Percent

Posted on May 2, 2011

Cradled Crescent, El Capitan and Half Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS 1DS Mark III

4 seconds

400 mm

ISO 400

F8

Thomas Edison said, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” (Without claiming genius) I think this applies to photography as well: Many successful images are more the product of being in the right place at the right time than divine inspiration. Of course anyone can stumble upon a lucky convergence of location and conditions and come home with a great photo, but the “genius” behind creating great photos consistently is preparation and sacrifice–a.k.a., perspiration.

The moonrise on the final sunrise shoot of last week’s Yosemite workshop spurred these thoughts about inspiration and effort. We were all in more or less the same place, photographing the same thing. And while everyone probably captured very similar images (in this case of a crescent moon squeezing between El Capitan and Half Dome), the true magic was simply being there.

But why were we the only ones there to witness this special moment that probably won’t repeat for decades? Determining the moon’s altitude and azimuth from any location on Earth is as easy as visiting one of many websites, or using one of many astronomical software applications such as The Photographer’s Ephemeris or (my preference) the Focalware iPhone app. Armed with this data, aligning the moon’s rise with any landmark isn’t rocket science.

Based on my calculations and plotting, I scheduled my “Yosemite Dogwood and Rising Crescent” workshop to coincide with a sunrise crescent moon. The dogwood bloom isn’t as reliable, but I know interesting weather is still possible in Yosemite in late April and early May. What we ended up with was mostly clear skies (great for tourists, but definitely not for photographers) and a very late dogwood bloom in Yosemite (probably two weeks behind “schedule”), forcing me to shift the daytime emphasis of my spring workshop to rainbows. I’m happy to report Bridalveil and Yosemite Falls delivered more photogenic rainbows than I can count, from a number of different locations.

As spectacular as they were, overshadowing the rainbows was the moonrise on our penultimate morning. I promised the group that departing at 4:50a.m. would get us to Tunnel View in time to photograph a 7% crescent moon rise above Yosemite Valley, between Sentinel Dome and Cathedral Rocks, in the pre-dawn twilight. (I knew this because I’ve been calculating moonrise and moonsets in Yosemite and elsewhere for many years, and have photographed more of these from Tunnel View than any other location.) That moonrise came off exactly as advertised–so far so good.

But the Tunnel View success, as beautiful as our images were, was merely a warm-up that gave everyone an opportunity to hone their silhouette exposure and composition skills in advance of the rare moonrise opportunity I’d planned for the next morning. When scheduling this workshop I’d determined that about 45 minutes before sunrise on May 1 of this year (2011), a delicate 3% crescent moon would slip into the narrow gap between El Capitan and Half Dome for anyone watching from Half Dome View on Big Oak Flat Road.

Lunar tables assume a flat horizon, so unless I’m at the ocean, the primary uncertainty is when the moon will appear above (or disappear below) the not-flat horizon. Once I’ve photographed a moonrise (or set) from a location, I simply check the precise time of its appearance (or disappearance) against the altitude/azimuth data for that day to get the exact angle of the horizon from there. Until I have this horizon information, I only have the moon’s direction and elevation above the unobstructed horizon and can only make an educated guess as to the time and location of its appearance.

The other big wildcard in moon and moonlight photography is the weather, but a last minute check with the National Weather Service confirmed that all systems were go there. Nevertheless, despite all my obsessive plotting, checking, and double-checking, having never photographed a moonrise from this location, and the fact that an error would affect not just me but my entire group, I couldn’t help feel more than a little anxious.

The afternoon before our second and final pre-dawn moonrise, I brought the group to Half Dome View so they could familiarize themselves with the location and plan their compositions. Due to the horizon uncertainties I just described, the first time I photograph a moonrise/set from a location, I generally give my group only an approximate time and position for the moon’s rise/set. But during this preview someone asked exactly where the moon would rise, and I confidently blurted that it will appear in the small notch separating El Capitan and Half Dome between 5:15 and 5:20 a.m. (about 25 minutes after the official, flat-horizon moonrise). Standing there that afternoon, however, I realized how small the notch really is, meaning that even the slightest error in my plotting could find the moon rising much later, from behind El Capitan or Half Dome. So I quickly qualified my prediction, explaining that I’ve never photographed a moonrise here and the uncertainty of knowing the horizon. But given all of my perfectly timed waterfall rainbow hits so far, not to mention our Tunnel View moonrise success earlier that morning, I had the sense that my group had unconditional (blind) confidence in me. (Yikes.)

Sunday morning we departed dark and early (4:45 a.m.), full of anticipation. We arrived at Half Dome View a little after 5:00, early enough to enable everyone to set up their tripods, frame their compositions, and set their exposures. Then we waited, all eyes locked on the gap separating El Capitan and Half Dome. Well, almost all eyes–mine made frequent detours to my watch and the Focalware iPhone app responsible for my bold (rash?) prediction. (What was I thinking, promising a moonrise into a paper-thin space in a five minute span from a spot where I’d never photographed a moonrise?) My watch crawled toward the 5:15-5:20 window: 5:15 (Is the notch shrinking?); 5:16 (It’s shrinking–I swear I just saw Half Dome inch closer to El Capitan); 5:17 (I entered the coordinates wrong, I know I did–what if it comes up behind us?). Surely this wasn’t the kind of perspiration Edison was thinking about.

As I frantically re-checked my iPhone for the umpteenth time, somebody exclaimed, “There it is!” I looked up and sure enough, there was the leading sliver of nearly new moon perfectly threading that small space between El Capitan and Half Dome. Phew. The rest of the morning was a blur of shutter clicks and exclamations of delight (plus one barely audible sigh of relief). (How could I have even dreamed of doubting the tried and true methods that had never failed me before?)

Before the shared euphoria abated, I suggested to everyone that they take a short break from photography and simply appreciate that they’re probably witnessing the most beautiful thing happening on Earth at this moment (a feeling every nature photographer should experience from time to time). It’s always exciting to witness a moment like this, a breathtaking convergence of Earth and sky that may not occur again exactly like this in my lifetime. It’s even more rewarding when the event isn’t an accident, that I’m experiencing it because of my own effort, and that I get to share the fruit of my perspiration with others who appreciate the magic just as much as I do.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A Crescent Moon Gallery

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: El Capitan, Half Dome, Moon, Photography Tagged: crescent moon, El Capitan, Half Dome, moon, Photography, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About