Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Trust your instincts

Posted on January 20, 2012

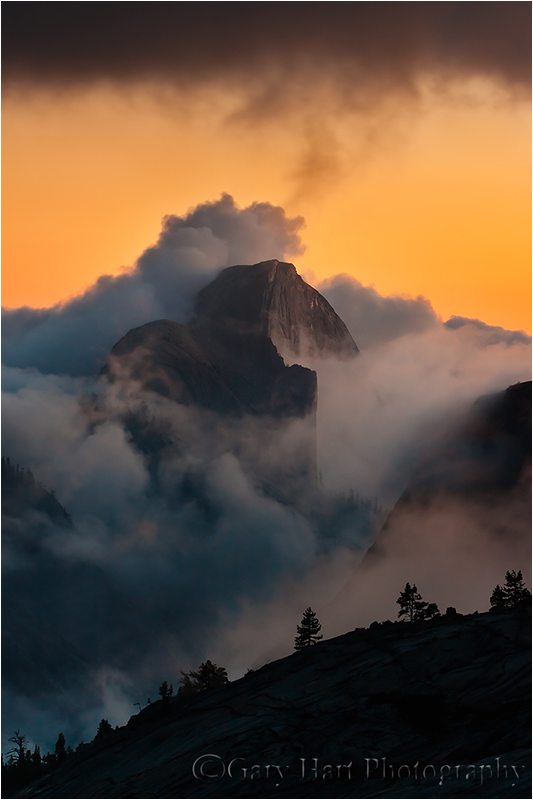

Emergence, Half Dome from Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

70-200L F4

3.2 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

This week I’ve spent some time going through past images that I just haven’t had time to get to. Unlike many of the images I uncover by returning to old shoots, this one from the final night of my October 2010 Eastern Sierra workshop wasn’t a surprise–the sky over Half Dome that night was magic, something I’ll never forget. Shortly after returning home I selected and processed one, but in conditions like that I always shoot enough variety of compositions that I knew there must be more there. While I have a general rule to only select one image of any scene from a single shoot, this is a perfect example of why I refuse to be bound by rules.

From the Clouds, Half Dome from Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

24-105L F4

5 seconds

F/16

ISO 400

Comparing the two images from that night, what strikes me most isn’t the similarity, but the differences. Despite being captured less than a minute apart, they illustrate creative choices that underscore a point I keep hammering on: Photographers are under no obligation to reproduce human “reality” (because it can’t be done). Because photographic reality is an impossible moving target, my obligation as a photographer is to my camera’s reality. And if I do things right, I can use my camera’s reality to transcend visual reality and convey some of the emotion of the moment.

So, in the “Emergence” (tight vertical) composition, I chose to emphasize Half Dome’s power and nothing else. I centered Half Dome and exposed for its granite face, letting the swirling clouds darken and the foreground go completely black. The dark clouds above Half Dome cap the top of the scene–there’s really nowhere else for your eye to go than Half Dome.

Today’s “From the Clouds” composition is more about the moment’s grandeur. I widened the perspective considerably and brightened my exposure enough to encourage your eye to wander about the frame a bit. There’s no question as to where your eye will end up, it just takes a little longer to get there. In other words, expanding the perspective and providing more light invites you to leave and return to Half Dome at your leisure.

Did I consciously plot this that night? Nope. Honestly, I’m rarely this analytical when I shoot–I just don’t want my left (logical) brain to distract my right (creative) brain. But I do believe that if you cultivate (and trust!) your intuition, creative decisions like this will happen organically. (But learn metering and exposure until it becomes automatic!)

So while I had no conscious thought of how to control your experience of this scene, I’ve done this long enough to know that these creative choices don’t just happen by accident. Without getting into the divine intervention claims trumpeted by some photographers (label it what you will), I believe everyone can access untapped creative potential that takes them far beyond what can be accomplished with the conscious mind. And it starts with trust.

BTW—I prefer the first one (Emergence).

Category: Half Dome, Olmsted Point, Photography Tagged: Half Dome, Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Have you ever seen a moonbow?

Posted on December 29, 2011

I’m fortunate to have a ringside seat for many of Mother Nature’s most exquisite phenomena, but few excite me more than the shimmering arc of Yosemite’s moonbow. A “moonbow”? I thought you’d never ask….

As you may have figured, a moonbow is a rainbow caused by moonlight. (Don’t be fooled by the fact that your spellcheck doesn’t recognize “moonbow”–it’s a very real thing indeed, and the more technically correct “lunar rainbow” designation just doesn’t seem to convey the magic.) Because a moonbow is a rainbow, all the natural laws governing a rainbow apply. But all this physics isn’t as important as simply understanding that your shadow always points toward the center of the rainbow/moonbow; the rainbow/moonbow will only appear when the sun/moon is 42 or fewer degrees above the horizon (assuming a flat horizon)–the higher the moon/sun, the lower the rainbow. When the moon or sun is above 42 degrees, the rainbow disappears below the horizon.

Each spring, High Sierra snowmelt surges into Yosemite Creek, racing downhill and plunging into Yosemite Valley below. A Yosemite icon, Yosemite Falls drops 2,500 feet in three magnificent, mist-churning steps. On spring full moon nights, light from the rising moon catches the mist, which bends it into a shimmering arc. John Muir called this phenomenon a “mist bow,” but it’s more commonly known today as a moonbow.

While a bright moonbow is visible to the naked eye as a (breathtaking) silver band, revealing the bow’s color requires the camera’s ability to accumulate light. The above image, from a couple of years ago, was captured near the bridge at the base of Lower Yosemite Fall. Not only was it crowded (the moonbow is no longer much of a secret), wind and mist made the necessary 20- to 30-second exposures an exercise in persistence. To include the Big Dipper in this frame (I love the way it appears to be the source of the fall), I composed vertical and wide (19mm). This was a 30 second exposure at f4 and ISO 400.

Understanding the basic physics of a rainbow makes it possible to photograph a moonbow from other, less crowded locations in Yosemite Valley. In the image on the left, the moon had climbed so high that the moonbow had almost dropped from view. And it was so small at this point that I couldn’t see it at all with my unaided eyes. But I knew it would be there, so I exposed the scene enough to make it nearly daylight bright, again orienting the composition vertical and wide to include the Big Dipper.

<< FYI, as of this writing, I still have a couple of openings in my two 2012 Yosemite Moonbow photo workshops, April 2-5 and May 2-5. >>

Category: Moon, Moonbow, Moonlight, Photography, Yosemite, Yosemite Falls Tagged: moonbow, Yosemite

Finding order in nature, one leaf at a time

Posted on December 6, 2011

“Did you put that leaf there?”

I’m frequently asked if I positioned a leaf, moved a rock, or “Photoshopped” a moon into an image. My (truthful) answer is always the same: “No.” I suspect I’m asked this so much because I aggressively search for natural elements and patterns to isolate and emphasize–they’re not hard to find if you look.

We all know photographers who have no qualms about arranging their scenes to suit their personal aesthetics. The rights and wrongs of that are an ongoing debate I won’t get into. But the pleasure I get from photography derives from revealing nature, not manufacturing it. There’s enough naturally occurring beauty to keep me occupied for the rest of my life.

Natural order

Nature is inherently ordered–in the big picture “nature” and “order” are synonyms. But humans go to great lengths to control, contain, and manage the natural world. We have a label for our failure to control nature: chaos. Despite its negative connotation, what humans perceive as “chaos” is actually just a manifestation of the universe’s inexorable push toward natural order.

For example

Imagine all humans suddenly removed from Earth. No lawns would be mowed, buildings maintained, floods “controlled,” oil drilled, etc. Let’s say we return in 100 years–while the state of things would no doubt be perceived as chaos, the reality is that our planet would in fact be closer to its natural state. And the longer we’re away, the more human-imposed “order” would be replaced by natural order.

Embracing the concept that nature is inherently ordered makes it easier to find order when you explore the world with your camera; photographic success suddenly becomes a function of your ability to convey nature’s order with your camera. Elements and relationships, lost in the confusion of 360 degree human sensory input, can snap into coherence in the rectangular confines of a photograph.

What does all this have to do with a leaf on a rock?

The leaf clinging to a wet rock was just one of thousands of colorful leaves decorating the cascades of Bridalveil Creek in Yosemite. By carefully positioning it within the finite boundaries of my frame, I was able to make the leaf stand out from the confusion of the competing elements surrounding me. In other words, I’m controlling your experience of this moment by giving your eyes a single element on which to focus, and capturing it against a simple background that allows you to plug in your own sensory memories. Hear the water? Feel the chill?

An autumn gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Creek, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: fall color, Yosemite

Seeing the small stuff

Posted on November 28, 2011

* * * *

In a recent post I mentioned that I don’t photograph Yosemite’s Tunnel View much anymore. It’s not that I visit Tunnel View any less frequently, or love being there any less than I once did; it’s more the growing realization collecting images already done (by myself or others) doesn’t really excite me. The longer I do this, the more I appreciate the simple pleasure of capturing a moment in nature, of finding a small detail or ephemeral scene that’s often overlooked and will never be repeated.

On a recent fall visit to Yosemite I meandered the bank of the Merced River near the Pohono Bridge and Fern Spring. As is often the case this time of year, a number of photographers were stationed on and near the bridge, and the usual swarm of tripods jockeyed for position around the spring. But the world was blissfully quiet among the trees. While the dogwood, usually fiery red in early November, were still mostly green, the maples flashed brilliant yellow. Even the slightest breeze sent a few leaves wafting, but closer scrutiny of those still holding tight showed many with a few molecules of spring green, a sign that the fall display wasn’t quite finished.

Positioning myself beneath an overhanging branch, I zoomed my 70-200 tight, separating the branch from its surroundings to make it appear suspended in midair. Despite a gray overcast and dark evergreen canopy, a few dots of light leaked through overhead. Usually I’ll compose bright sky out of a frame like this, but here I decided to feature it, dialing in a large aperture (f5.6) to soften the individual pinpoints into overlapping jewels. Because a narrow depth of field makes the focus point particularly critical, I switched to live-view and magnified my LCD to ensure precise focus. The narrow depth of field also smoothed the background trees, erasing distractions and setting the sharp foreground leaves against a complementary canvas of color, shape, and light.

These leaves are brown now, decomposing on the forest floor, or perhaps far downriver. While there’s no doubt in my mind that as I clicked this frame many simultaneous clicks captured whatever was going on at Tunnel View, I’m pretty sure I’m the only person in the world with this image. That’s a nice thought for sure, until I remember that within a few feet of where I stood were an infinite number of other unrepeatable images that I missed. Guess I’ll just have to keep trying….

Category: Yosemite Tagged: fall color, Yosemite

Magenta moonrise, Half Dome, Yosemite

Posted on November 21, 2011

With my camera I’m able to create my own version of any view, adjusting focal length (the amount of magnification) and composition to emphasize whatever elements and relationships I find most compelling. Today’s image was captured on the final shoot ofmy most recent fall workshop, three sunsets after my previous image, from virtually the same location.

On Sunday evening (the first sunset), with Yosemite Valley emerging from swirling clouds and the moon high above Leaning Tower, I chose a wide composition that encompassed the entire scene. Wednesday evening the eastern horizon was partially obscured by a uniform layer of translucent clouds. As the sunset progressed, we watched the moon’s glow rise through the throbbing pink clouds. When it slipped into a small opening I quickly tightened my composition to create a frame that was all about Half Dome and the moon. I made the Sunday moon a delicate accent, the Wednesday moon a bold exclamation point. These decisions remind me that photography is more than simply documenting a moment; it’s taking that moment and using the camera’s unique vision to convey its essence.

One more thing: By the last day of a workshop, relationships have been forged and inside jokes have blossomed. The group interaction feels more like a family gathering (minus the disfunction) than the assembly of diverse strangers we were three-and-a-half days earlier. On this evening in particular we had a great time laughing about things that anyone who hadn’t been in the workshop couldn’t appreciate. It was lots of fun, and a wonderful way for me to wrap up this year’s fall workshop season.

Isolation

Posted on November 11, 2011

I love sweeping panoramas, but when I’m alone I often gravitate to the intimate locations that make nature so personal. In Yosemite’s dark corners, places like Bridalveil Creek beneath Bridalveil Fall, and the dense mix of evergreen and deciduous trees lining Merced River near Fern Spring and the Pohono Bridge, I scour the trees and forest floor for subjects to isolate from their surroundings.

Helping your subjects stand out is often the key to a successful image. Sometimes subject isolation is a simple matter of finding something that stands out from its surroundings, an object that’s physically separated far from other distractions. But more often than not, effective isolation requires a little help from your camera settings, using contrast, focus, and/or motion to distinguish it from nearby distractions.

A disorganized tangle of weeds or branches can become a soft blur of color when you narrow your depth of field with a large aperture, close focus point, and/or long focal length. Likewise with motion, where a long shutter speed can smooth a rushing creek into a silky white ribbon. And a camera’s inherently limited dynamic range can render shadows black, and highlights white, creating a perfect background for your subject.

After finding these dangling leaves, just across the road and a little downriver from Fern Spring in Yosemite Valley, I juxtaposed them against the vertical trunks of background maples and evergreens. Zooming to 200mm reduced my depth of field, separating the sharp leaves from the soft background of trunks and branches. A large aperture further blurred the background to a simple, complementary canvas of color and shape. Slight underexposure and a polarizer (to remove glare) helped the color pop.

On my website you can read more about my favorite Yosemite photo locations.

A gallery of isolation

Category: fall color, How-to, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: macro, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

A landscape photographer’s time

Posted on June 25, 2011

On my run this morning I listened to an NPR “Talk of the Nation” podcast about time, and the arbitrary ways we Earthlings measure it. The guest’s thesis was that the hours, days, and years we measure and monitor so closely are an invention established (with increasing precision) by science and technology to serve society’s specific needs; the question posed to listeners was, “What is the most significant measure of time in your life?” Most listeners responded with anecdotes about bus schedules, school years, and work hours that revealed how our conventional time measurement tools, clocks and calendars, rule our existence. Listening on my iPhone, I wanted to stop and call to share my own relationship with time, but quickly remembered I wasn’t listening in realtime to the podcast. So I decided to blog my thoughts here instead.

Landscape photographers are governed by far more primitive constructs than the bustling majority, the fundamental laws of nature that inspire, but ultimately transcend, clocks and calendars: the Earth’s rotation on its axis, the Earth’s revolution about the Sun, and the Moon’s motion relative to the Earth and Sun. In other words, clocks and calendars have little to do with the picture taking aspect of my life; they’re useful only when I need to interact with the rest of the world on its terms (that is, run the business).

While my years are ruled by the changing angle of the Sun’s rays, and my days are inexorably tied to the Sun’s and Moon’s arrival, I can’t help fantasize about the ability to schedule my spring Yosemite moonbow workshops (that require a full moon) for the first weekend of each May, or mark my calendar for the blizzard that blankets Yosemite in white at 3:05 p.m. every February 22. But Nature, despite human attempts to manipulate and measure it, is its own boss. The best I can do is adjust my moonbow workshops to coincide with the May (or April) full moon each year; or monitor the weather forecast and bolt for Yosemite when a snowstorm is promised (then wait with my fingers crossed).

The insignificance of clocks and calendars is never more clear than the first morning following a time change. On the last Sunday of March, when “normal” people moan about rising an hour earlier, and the first Sunday of November, as others luxuriate in their extra hour of sleep, it’s business as usual for me. Each spring, thumbing its nose at Daylight Saving Time, the Sun rises a mere minute (or so) earlier than it did the day before; so do I. And each fall, on the first sunrise of Standard Time, I get to sleep an an entire minute longer. Yippee.

Honestly, I love nature’s mixture of precision and (apparent) randomness. I do my best to maximize my odds for something photographically special, but the understanding that “it” might not (probably won’t) happen only enhances the thrill when it, or maybe something unexpected and even better, does happen. The rainbow in today’s image was certainly not on anybody’s calendar; it was a fortuitous convergence of rain and sunlight (and ecstatic photographer). My human “schedule” that evening was a 6 p.m. get-to-know/plan-tomorrow dinner meeting with a private workshop customer. But seeing the potential for a rainbow, I suggested that we defer to Mother Nature, ignore our stomachs, and go sit in the rain. Fortunately he agreed, and we were amply rewarded for our inconvenience and discomfort.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Gallery of Rainbows

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, Photography, rainbow, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, El Captian, Half Dome, nature photography, Photography, Rainbow, Yosemite

The Other Ninety-Nine Percent

Posted on May 2, 2011

Cradled Crescent, El Capitan and Half Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS 1DS Mark III

4 seconds

400 mm

ISO 400

F8

Thomas Edison said, “Genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” (Without claiming genius) I think this applies to photography as well: Many successful images are more the product of being in the right place at the right time than divine inspiration. Of course anyone can stumble upon a lucky convergence of location and conditions and come home with a great photo, but the “genius” behind creating great photos consistently is preparation and sacrifice–a.k.a., perspiration.

The moonrise on the final sunrise shoot of last week’s Yosemite workshop spurred these thoughts about inspiration and effort. We were all in more or less the same place, photographing the same thing. And while everyone probably captured very similar images (in this case of a crescent moon squeezing between El Capitan and Half Dome), the true magic was simply being there.

But why were we the only ones there to witness this special moment that probably won’t repeat for decades? Determining the moon’s altitude and azimuth from any location on Earth is as easy as visiting one of many websites, or using one of many astronomical software applications such as The Photographer’s Ephemeris or (my preference) the Focalware iPhone app. Armed with this data, aligning the moon’s rise with any landmark isn’t rocket science.

Based on my calculations and plotting, I scheduled my “Yosemite Dogwood and Rising Crescent” workshop to coincide with a sunrise crescent moon. The dogwood bloom isn’t as reliable, but I know interesting weather is still possible in Yosemite in late April and early May. What we ended up with was mostly clear skies (great for tourists, but definitely not for photographers) and a very late dogwood bloom in Yosemite (probably two weeks behind “schedule”), forcing me to shift the daytime emphasis of my spring workshop to rainbows. I’m happy to report Bridalveil and Yosemite Falls delivered more photogenic rainbows than I can count, from a number of different locations.

As spectacular as they were, overshadowing the rainbows was the moonrise on our penultimate morning. I promised the group that departing at 4:50a.m. would get us to Tunnel View in time to photograph a 7% crescent moon rise above Yosemite Valley, between Sentinel Dome and Cathedral Rocks, in the pre-dawn twilight. (I knew this because I’ve been calculating moonrise and moonsets in Yosemite and elsewhere for many years, and have photographed more of these from Tunnel View than any other location.) That moonrise came off exactly as advertised–so far so good.

But the Tunnel View success, as beautiful as our images were, was merely a warm-up that gave everyone an opportunity to hone their silhouette exposure and composition skills in advance of the rare moonrise opportunity I’d planned for the next morning. When scheduling this workshop I’d determined that about 45 minutes before sunrise on May 1 of this year (2011), a delicate 3% crescent moon would slip into the narrow gap between El Capitan and Half Dome for anyone watching from Half Dome View on Big Oak Flat Road.

Lunar tables assume a flat horizon, so unless I’m at the ocean, the primary uncertainty is when the moon will appear above (or disappear below) the not-flat horizon. Once I’ve photographed a moonrise (or set) from a location, I simply check the precise time of its appearance (or disappearance) against the altitude/azimuth data for that day to get the exact angle of the horizon from there. Until I have this horizon information, I only have the moon’s direction and elevation above the unobstructed horizon and can only make an educated guess as to the time and location of its appearance.

The other big wildcard in moon and moonlight photography is the weather, but a last minute check with the National Weather Service confirmed that all systems were go there. Nevertheless, despite all my obsessive plotting, checking, and double-checking, having never photographed a moonrise from this location, and the fact that an error would affect not just me but my entire group, I couldn’t help feel more than a little anxious.

The afternoon before our second and final pre-dawn moonrise, I brought the group to Half Dome View so they could familiarize themselves with the location and plan their compositions. Due to the horizon uncertainties I just described, the first time I photograph a moonrise/set from a location, I generally give my group only an approximate time and position for the moon’s rise/set. But during this preview someone asked exactly where the moon would rise, and I confidently blurted that it will appear in the small notch separating El Capitan and Half Dome between 5:15 and 5:20 a.m. (about 25 minutes after the official, flat-horizon moonrise). Standing there that afternoon, however, I realized how small the notch really is, meaning that even the slightest error in my plotting could find the moon rising much later, from behind El Capitan or Half Dome. So I quickly qualified my prediction, explaining that I’ve never photographed a moonrise here and the uncertainty of knowing the horizon. But given all of my perfectly timed waterfall rainbow hits so far, not to mention our Tunnel View moonrise success earlier that morning, I had the sense that my group had unconditional (blind) confidence in me. (Yikes.)

Sunday morning we departed dark and early (4:45 a.m.), full of anticipation. We arrived at Half Dome View a little after 5:00, early enough to enable everyone to set up their tripods, frame their compositions, and set their exposures. Then we waited, all eyes locked on the gap separating El Capitan and Half Dome. Well, almost all eyes–mine made frequent detours to my watch and the Focalware iPhone app responsible for my bold (rash?) prediction. (What was I thinking, promising a moonrise into a paper-thin space in a five minute span from a spot where I’d never photographed a moonrise?) My watch crawled toward the 5:15-5:20 window: 5:15 (Is the notch shrinking?); 5:16 (It’s shrinking–I swear I just saw Half Dome inch closer to El Capitan); 5:17 (I entered the coordinates wrong, I know I did–what if it comes up behind us?). Surely this wasn’t the kind of perspiration Edison was thinking about.

As I frantically re-checked my iPhone for the umpteenth time, somebody exclaimed, “There it is!” I looked up and sure enough, there was the leading sliver of nearly new moon perfectly threading that small space between El Capitan and Half Dome. Phew. The rest of the morning was a blur of shutter clicks and exclamations of delight (plus one barely audible sigh of relief). (How could I have even dreamed of doubting the tried and true methods that had never failed me before?)

Before the shared euphoria abated, I suggested to everyone that they take a short break from photography and simply appreciate that they’re probably witnessing the most beautiful thing happening on Earth at this moment (a feeling every nature photographer should experience from time to time). It’s always exciting to witness a moment like this, a breathtaking convergence of Earth and sky that may not occur again exactly like this in my lifetime. It’s even more rewarding when the event isn’t an accident, that I’m experiencing it because of my own effort, and that I get to share the fruit of my perspiration with others who appreciate the magic just as much as I do.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A Crescent Moon Gallery

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: El Capitan, Half Dome, Moon, Photography Tagged: crescent moon, El Capitan, Half Dome, moon, Photography, Yosemite

Make the world your own

Posted on January 19, 2011

Pretend you’re a musician who wants to make music your career. Let’s say Eric Clapton is your favorite artist, and “Layla” is your favorite song. Do you think your quickest path to fame and fortune would be to record a song that perfectly replicates “Layla”? (Especially given the difficulty you’d have resurrecting Duane Allman.)

So why is it that so many nature photographers with grand aspirations spend so much time trying to duplicate the shots of others, rather than trying to find and refine their own artistic vision? Using Eric Clapton as a model for your music is great—the more you listen to Clapton, the more your guitar playing will be influenced by his craftmanship. But at some point you need to choose between carving your own musical path or languishing in anonymity.

This applies equally in photography. In my photo workshops I encounter many people who have travelled a great distance to duplicate a photo they’ve seen online, in a book, or in a print. I certainly understand the impulse, and I can’t say that my portfolio doesn’t contain its share of these clichés. But, as I frequently urge my workshop students, if you must photograph something exactly as it’s been photographed before, make that version your starting point and not your ultimate goal.

Once you get your “iconic” (that word is a cliché itself) shot, slow down and work the scene. Look for foreground and background possibilities, find unique perspectives. Play with depth and motion. If your original frame was horizontal, try something vertical, and vice versa. Take your camera off the tripod and pan slowly, zooming in and out as you go until something stops you (don’t forget to bring the tripod back before clicking). Still feel uninspired? Try a longer lens—often the truly unique images are tighter shots that isolate elements of the conventional composition.

It’s true that the longer spend time with a scene, the more you’ll find to photograph. Make a mental checklist of the above steps (feel free to add your own) and go through them without rushing: Often the mere mechanical (uninspired) process of seeking something unique gives you deeper insight that leads to a creative capture if you stick with it long enough.

This image of El Capitan reflected in the Merced River resulted from just such an approach. I’d rolled into Yosemite at around 10:00 a.m. on a mid-November morning. The air was crisp and still, scoured clean by an overnight shower. At Valley View I found this perfect reflection, only possible in the quiet-water days of autumn. Working on a tripod, I started my compositions wide and captured many of the beautiful but conventional shots that have been done a million times here. But wanting something different, I removed my camera from my tripod continued probing the scene through my viewfinder. I eventually isolated the reflection, realizing it was so sharp the morning that it was the thing that really set this moment apart. Despite the advancing sunlight that would soon reach the river and wash out the reflection, I didn’t rush.

On my computer at home, it was fun to view my process through the series of captures that morning. I finally zeroed in on this frame that has become one of my most successful images. Did I create the photographic equivalent of “Layla” that morning? Doubtful. But I did come up with an image that pleases me, and something that’s a pretty unique take on this heavily photographed location.

Category: El Capitan, How-to, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, Photography, reflection, Yosemite

Are you a photographer or a tourist?

Posted on January 14, 2011

When the weather gets crazy, do you sprint for cover or reach for your camera? Your answer may be a pretty good predictor of your success as a photographer. It’s an unfortunate fact that the light, color, and drama that make memorable landscape photos all come when most sane people would rather be inside: at sunrise, when the rest of the world is asleep; at sunset, when everyone else is at dinner; and during wild weather, when anyone with sense is on the sofa in front of the fire.

Last spring I guided a photo workshop group through Yosemite. On the final day we circled Yosemite Valley in a steady rain, stopping to photograph many of my favorite cloudy-sky spots. Through it all my hardy group persevered, wet but happy, but by mid-afternoon their energy had started to wane a bit. Rather than risk mutiny, I detoured to Tunnel View to give everyone a breather.

With El Capitan, Half Dome, Cathedral Rocks, and Bridalveil Fall all on prominent display, it’s no secret why Tunnel View is the most photographed location in Yosemite. After a storm, Yosemite’s dramatic landmarks emerge from swirling clouds as if appearing on earth for the first time. Storms in Yosemite clear from west to east, making Tunnel View the first place to capture this unforgettable experience and my go-to place to wait out Yosemite weather.

The rain fell in sheets as we pulled into the Tunnel View parking area. Throughout the workshop I’d tried to impress on everyone how quickly conditions change in Yosemite, but it’s pretty hard to appreciate exactly how quickly until you actually experience a change yourself. So, despite my prodding to the contrary, when I donned my rain gear and invited the group to join me in the rain, they all opted for the warmth of the cars. And there I stood, five soggy minutes later, accompanied only by my tripod and camera (me beneath an umbrella, my camera beneath a plastic garbage bag), when without warning a ray of sunlight broke through, briefly painting a rainbow above Yosemite Valley, from El Capitan to Bridalveil Fall. After rousing the group I had time for three frames before the rainbow faded into the clouds. Everyone else was still wrestling with their gear.

Did I know a rainbow was going to happen? Of course not. In fact, if I were a betting man, I’d have wagered I wasn’t going to get anything but wet. But no matter how slim the odds were, a special image was infinitely more likely in the rain than in the car.

So. Are you a photographer or a tourist? There’s nothing wrong with the tourist mentality that only takes you outdoors with the masses, well rested and appetite sated in midday warmth. On the other hand, if one spectacular success is compensation enough for the other hundred tired, hungry, cold, and wet failures, you may just be a photographer.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: Photography, Rainbow, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About