Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

The twilight edge

Posted on January 16, 2015

I sometimes hear comments and questions that make me think people believe pro photographers have “secrets” that enable us to photograph things the amateur public can’t. Let me assure you that this is not true. What is true is that successful landscape photographers have an understanding of the natural world that helps us know where and when to look for our images, and we know that often the best pictures aren’t in the same place as the best view.

For example, it’s hard to deny the beauty of a sunrise or sunset. But it seems that most people are so mesmerized by the scene facing the sun that they miss exquisite beauty in the other direction. The next time you find yourself out photographing (or simply enjoying) a sunrise or sunset, do yourself a favor and check out the world behind you. Beneath clear skies you’ll see the earth’s shadow, often called the “twilight wedge,” overlaid by the pink “Belt of Venus.” I call the sky in this direction the “twilight edge,” not only because it’s found at the day’s leading or trailing edge, but also for the advantage it gives photographers who understand how easy this under-appreciated (and oft missed) perspective is to photograph.

Unlike the view toward the rising or setting sun, where cameras struggle to expose the full range of shaded subjects against a bright sky, the scene opposite the sun is bathed light that has been bent, scattered, colored, and subdued by its long trip through the atmosphere. While not as dramatic to the eye as an electric crimson sky or throbbing orange sun, a camera loves the long shadows and warm tones away from the sun.

But the great light doesn’t begin at sunrise, or end at sunset. When the sun is about ten degrees or closer to the horizon, the sky in the opposite direction is bright enough to fill the landscape with soft, shadowless light that makes photography a breeze. And while the scene may appear quite dark to the eye, a long exposure and/or slightly higher ISO (like 400 or 800) will reveal the world in a way that’s impossible in daylight. Case in point:

Before Sunrise, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, California

This is a 30 second exposure at ISO 400, captured about 30 minutes before sunrise on a windy Eastern Sierra winter morning, when the world was still dark enough to require a flashlight to maneuver.

Twilight components

Above the shadowless pre-sunrise/post-sunset landscape, when the sun is around six degrees or closer to the horizon (civil twilight), soft bands of color stacked like pastel pillows materialize. The blue-gray band earth’s shadow directly above the horizon earned its “twilight wedge” designation because you can sometimes see the earth’s curve in the shadow, giving it something of a wedge shape. At sunset, the gradual upward motion of the shadow gives the appearance of a wedge being driven into the darkening sky.

Above the earth’s shadow, but not quite high enough to receive the full complement of solar wavelengths, the atmosphere basks in the slightly brighter pink glow of scattered sunlight. In this region the shorter wavelengths have been dispersed, leaving only the longest, red wavelengths—the Belt of Venus. You’ll first see its pink stripe high in the pre-sunrise sky, descending and brightening as the sun rises, until the pink is finally overcome by the first rays of sunrise; after sunset the pink band starts low, climbing skyward and darkening, eventually blending into the oncoming night.

Alpenglow

A particularly striking sunrise/sunset phenomenon is the “alpenglow” that spreads atop mountaintops that rise so far above the surrounding terrain that they jut into the BoV, assuming its pink glow. My favorite place to photograph alpenglow is the Alabama Hills, 10,000 vertical feet below Mt. Whitney and the Sierra crest, but alpenglow paints peaks throughout the world.

Alpenglow, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra

From my vantage point the sun was still well below the horizon, but Mt. Whitney, 10,000 feet above me jutted into the scattered pink rays of the rising sun.

Moonrise, moonset

Quite conveniently, the earth shadow and Belt of Venus also happen to be where you’ll find a setting (at sunrise) and rising (at sunset) full moon. If you’ve been paying attention, you know that the full moon (more or less) rises in the east at sunset, and sets in the west at sunrise. Many of my favorite images use just such a moonrise or moonset to accent an empty but colorful sky.

The image at the top of this post is a recent attempt at a sunrise moonset. I was in Big Sur last week to help my good friend Don Smith with his Big Sur winter workshop. Don and I guided the group down to the beach much too early to photograph the moon, but the extra time allowed everyone to search for a suitable foreground.

With the tide quite high, many of the beach’s most photogenic rocks were partially or completely submerged, but we certainly weren’t lacking for subjects. Don helped half of the group work the rocks along the south part of the beach, while the other half followed me north. Just a couple of hundred yards up the beach we found a pair of boulders amidst the crashing surf. Taking care not to scar the pristine sand with footprints, we spent the rest of the sunrise moving around, framing the setting moon with these and a couple of other nearby boulders.

I clicked the frame here extremely early in the window of usable light, when the foreground was just bright enough that capturing usable detail didn’t require overexposing the moon (remember, if I can’t capture the entire scene with one click, I won’t shoot it). Vanquishing this extreme dynamic range was aided by the amazing sensor of my new Sony a7R (thank you very much), combined with my trusty Singh-Ray 3-stop hard graduated neutral density filter.

Even with those advantages, I still needed to massage the shadows up and highlights (the moon only) down in Lightroom and Photoshop. The advantage of photographing the scene this early was the ability to capture the moonlight reflected on the ocean, something I’d have lost if I’d waited for the foreground to brighten.

A Gallery of the View Opposite the Sun

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh your screen to reorder the display.

Photo Workshops

Learn more and photograph these scenes yourself in a photo workshop

Category: Big Sur, full moon, Garrapata Beach, How-to, Moon Tagged: belt of Venus, Big Sur, full moon, moon, Photography, twilight wedge

World in motion

Posted on January 9, 2015

Moon on the Rocks, Soberanes Point, Big Sur

Sony a7R

Sony/Zeiss 16-35

5 seconds

F/11

ISO 200

As a full-time landscape photographer, I often joke that I don’t photograph anything that moves—no wildlife, no pets, no portraits, no sports. And don’t even think about asking me to do your wedding. I’ve always been a deliberate shooter who likes to anticipate and prepare my frame with the confidence my shot will still be there when I’m ready—landscape photography suits me just fine (thank-you-very-much).

But as much as I appreciate the comfortable pace of a static landscape, the reality is that nature is in constant motion. Earth’s rotation spins the moon and stars across our night sky, and continuously changes the direction, intensity, and color of the sunlight that rules our day. Rivers cascade toward sea level, clouds scoot and change shape overhead, ocean waves curl and explode against sand and rock, then vanish and repeat. And even a moderate breeze can send the most firmly rooted plants into a dancing frenzy.

Photographing motion is frustrating because a single image can’t duplicate the human experience (not to mention the technical skill required to subdue it without compromising exposure and depth). But motion also presents a creative opportunity for the photographer who knows how to create a motion-implying illusion that conveys power, flow, pattern, and direction.

While a camera can’t do what the human eye/brain do, it can accumulate seconds, minutes, or hours of activity with one “look,” recording a scene’s complete history in a single image. Or, a camera can document an instant, an ephemeral splash of water or bolt of lightning that’s gone so fast it’s merely a memory by the time a viewer’s conscious mind processes it. This is powerful stuff—accumulating motion in a long frame reveals hidden patterns; freezing motion saves an instant for eternal scrutiny.

For example

When I photograph the night sky, I have to decide how to handle the motion of the stars (insert obligatory, “It’s not the stars that are moving” comment here). Freezing celestial motion is a balancing act that combines a high ISO and large aperture with a shutter speed to maximize the amount of light captured, while concluding before discernable streaks form. My goal is to hold the stars in one spot long enough to reveal many too faint for the eye to register. Or, I can emphasize celestial motion by holding my shutter open for many minutes.

Lightning comes and goes faster than human reflexes can respond. At night, a long exposure can be initiated when and where lighting might strike, recording any bolt that occurs during the exposure. But in daylight I need a lightning sensing device like a Lightning Trigger, that detects the lightning and fires the shutter faster than I can.

Moving water is probably the most frequently photographed example of motion in nature, with options that range from suspended water droplets to an ethereal gauze. I’m always amused when I hear someone say they don’t like blurred water images because they’re not “natural.”

Ignoring the fact that it’s usually impossible to achieve a shutter speed fast enough to freeze airborne water in the best (shade or overcast) light, I don’t find blurred water any less natural than a water drop suspended in midair (when was the last time you saw that). Blurred water isn’t unnatural, it’s different.

Which brings me to the image at the top of the frame, of the waves and rocks at Big Sur’s of Soberanes Point, and a (nearly) full moon dropping through the twilight on the distant horizon. I could have increased my aperture and ISO until my shutter speed stopped the motion of the waves, and timing the exposure just right, might have recorded an explosive collision of wave and rock—dramatic, but understating turbulence of the ocean/land interface. Instead, I opted for an exposure long enough to convey the action and extent of the agitated surf, but fast enough to hold the setting moon in place.

A gallery of motion in nature

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh your screen to reorder the display.

Category: Big Sur, full moon, Garrapata Beach, Moon, Soberanes Point Tagged: Big Sur, full moon, moon, nature photography, Photography

Looking back, looking forward

Posted on December 29, 2014

For the final shoot of my final 2014 workshop, I guided my group up the rain-slick granite behind Yosemite’s Tunnel View for a slightly different perspective than they’d seen earlier in the workshop. I warned everyone that slippery rock and the steepness of the slope could make the footing treacherous (and offered a safer alternative), but promised the view would be worth it. Then I crossed my fingers.

While sunset at Tunnel View is often special, the rare sunset event I’d been pointing to for over a year, a nearly full (96%) moon rising into the twilight hues above Half Dome, is a particular highlight, one of my favorite things in the world to witness. But after an autumn dominated by clear skies that would have been perfect for our moonrise, a much needed storm landed just as our workshop started, engulfing Yosemite Valley in dense clouds, recharging the waterfalls, and painting the surrounding peaks white. Rain clouds make great photography, but they’re not so great for viewing the moon.

As you can see from this image, the clouds this evening cooperated, glazing the valley floor, but parting above Half Dome enough to reveal the moon. The moon was already high above Half Dome when it peeked out, and shortly thereafter the retreating storm’s vestiges were fringed with sunset pink. As I often do at these moments, I encouraged everyone to forget their cameras for a minute and just appreciate that they may be viewing the most beautiful thing happening on Earth at this moment. Together we enjoyed what was a once-in-a-lifetime moment for them, and a fitting conclusion to another wonderful year of photography for me.

Like any other photographer who makes an effort to get out in difficult, unpredictable conditions, I had many of these “most beautiful thing on Earth” moments in 2014—they’re what keep me going. The last couple of weeks I’ve been browsing my 2014 captures and re-appreciating my blessings. Among other things, in 2014 I rafted the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, was humbled by the Milky Way’s glow above the Kilauea Caldera, shivered beneath starlit bristlecone pines, and was electrified by the Grand Canyon monsoon’s pyrotechnics.

Most of my trips start with a plan, and while a lot of my 2o14 experiences followed the script, many deviated from my expectations, often in wonderful ways. My original vision of the moonrise on this December evening was clear skies that would allow the moon to shine; an alternate vision was a sky-obscuring storm that provided photogenic clouds. We ended up with the best of both, a hybrid of clouds and sky that I dared not hope for.

While I have a general plan in place for 2015, some places I’ll be returning to, others I’ll photograph for the first time, I know from experience that my plans won’t always go as planned. Clouds will hide the moon and stars, clear skies will cast harsh light, rivers will flood, waterfalls will wither, rivers will flood. But I also know that many of those thwarted plans will lead to unexpected rewards like this.

Here’s to a great 2015!

2014 in Review

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh your screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, full moon, Half Dome, Moon, Photography, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Revisiting Photography’s 3 P’s

Posted on December 15, 2014

Parting the Clouds, Yosemite Valley Moonrise, Tunnel View

Sony a7R

72 mm

1/15 second

F/11

ISO 100

Let’s review

I often speak and write about “The 3 P’s of nature photography,” sacrifices a nature photographer must make to consistently create successful images.

- Preparation is your foundation, the research you do that gets you in the right place at the right time, and the vision and mastery of your camera that allows you to wring the most from the moment.

- Persistence is patience with a dash of stubbornness. It’s what keeps you going back when the first, second, or hundredth attempt has been thwarted by unexpected light, weather, or a host of other frustrations, and keeps you out there long after any sane person would have given up.

- Pain is the willingness to suffer for your craft. I’m not suggesting that you risk your life for the sake of a coveted capture, but you do need to be able to ignore the tug of a warm fire, full stomach, sound sleep, and dry clothes, because the unfortunate truth is that the best photographs almost always seem to happen when most of the world would rather be inside.

Picking an image and trying to assign one or more of the 3 P’s to it is a fun little exercise I sometimes use to remind myself to keep doing the extra work. Take a few minutes to scan your favorite captures; ask yourself how many didn’t require at least one of the 3 P’s. (I’ll wait.) …….. See what I mean?

So which of my 3 P’s do I credit for this one? Well, there was the Persistence to continue going out in the rain all week, with no guarantee we’d see anything beyond 100 yards (because in Yosemite, if you stay inside until the rain stops, you’re too late). And of course photographing in the rain is nothing if not a Pain. But more than anything else, this one was about…

Preparation

(If you discount the unavoidable knowledge gained by a lifetime of Yosemite visits and and decades of plain old picture clicking) the preparation for this image started when I plotted the 2014 December moon and determined that it would rise at sunset, nearly full, above Half Dome in the month’s first week. So of course I scheduled a workshop for that week.

But there was more to the preparation than just figuring out where the moon would be. Of course as the workshop approached, I monitored the weather forecast and arrived in Yosemite prepared for rain. (Duh.) And throughout the workshop I monitored the weather obsessively, scouring each National Weather Service forecast update (every six hours), monitoring radar, not to mention the good old fashioned walk-outside-and-look-up technique.

Before going out for our penultimate afternoon shoot, I determined exactly what time the moon would appear above Half Dome, though I had little hope that the clouds would part enough to reveal it. Nevertheless, I wanted to to keep the group within striking distance of Tunnel View, just in case. When the latest weather forecast indicated a possible break in the rain late that afternoon, I started watching the sky closely—a clearing storm plus the moon would be pretty cool for everyone (including this life-long Yosemite photographer). The instant the clouds showed a hint of brightening (a subtle precursor to an imminent break that every photographer should be able to read), I raced everyone back up to Tunnel View.

As we pulled into the Tunnel View lot, not only was the storm starting to clear, a small patch of the first blue sky we’d seen in two days was widening above Half Dome. I held my breath and crossed my fingers for the blue to expand just a little more, because I knew exactly where the moon was and it was oh so close.

We didn’t need to wait long—within five minutes a thin piece of moon poked through, then a little more, and soon there it was, floating in that small blue patch between Half Dome and Sentinel Dome. It hung in there for less than five minutes before the clouds regrouped and swallowed the sky.

Epilogue

With more rain in the forecast, driving down from Tunnel View that night I felt certain that this unexpected, brief convergence of moon and sky was a one-time gift, that the planned moonrise for our final sunset would surely be lost to the clouds. And given what we’d just seen, I was okay with that. But Nature had a different idea….

A Gallery of Extreme Weather Rewards

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Bridalveil Fall, full moon, Half Dome, Moon, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, full moon, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Moon whisperer

Posted on November 14, 2014

Just when you start getting cocky, nature has a way of putting you back in your place. Case in point: last week’s full moon, which my workshop group photographed to great satisfaction from the side of Turtleback Dome, near the road just above the Wawona Tunnel.

I love photographing the moon, in all of its phases for sure, but especially in its full and crescent phases, when it hangs on the horizon in nature’s best light. I’ve developed a method that allows me to pretty much nail the time and location of the moon’s appearance from any location, and love sharing the moment with my workshop students. (Because my workflow has been in place for about ten years, I don’t use any of the excellent new software tools that automate the moon plotting process.)

Last week’s workshop was no exception, and after much plotting and re-plotting, I decided that rather than my usual Tunnel View vantage point, the view just west of the Wawona Tunnel would work better for this November’s full moon. Arriving about 30 minutes before “showtime,” I gathered everyone around and pointed a spot on Half Dome’s right side, about a third of the way above the tree-lined ridge, and told them the moon would appear right there between 4:45 and 4:50.

Sure enough, right at 4:47 there it was and I exhaled. We photographed the moon’s rise for about 30 minutes, until difference between the darkening valley and daylight-bright moon became too great for our cameras to capture lunar detail. Everyone was thrilled, and I was an instant genius—I believe I even heard “moon whisperer” on a few lips.

The workshop wrapped up the next evening, and I was still basking in my new-found moon whisperer status as I drove home down the Merced River Canyon with my daughter Ashley in the passenger seat. In a car behind us was workshop participant Laurie, who had never been down that road and wanted to follow me to the freeway in Merced.

Hungry, we stopped at one of my favorite spots, Yosemite Bug Rustic Mountain Resort in Midpines (check it out), for dinner. About an hour later, our stomachs full, we were walking back to the cars when someone pointed to a glow atop the mountain ridge above the resort. Ashley and I recognized it as the rising moon, but since this wasn’t a full disk, immediately entered into a friendly debate as to whether the moon was just peeking above the ridge, or had already risen and was disappearing behind a cloud.

We actually got quite scientific, escalating the passion with each point/counterpoint to make our cases (lest you think this was an unfair contest, I should add that Ashley’s a lawyer). Laurie remained silent. I’m not really sure how long we’d been debating when Laurie finally nudged us and pointed skyward, where, in full view of the entire Western Hemisphere, glowed the landscape illuminating spotlight of the actual full moon. Moon whisperer indeed.

(We never did figure out what the glow was.)

A full moon gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, Humor, Moon Tagged: El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Plan B

Posted on October 30, 2014

I usually approach a scene with a plan, a preconceived idea of what I want to capture and how I want to do it. But some of my favorite images are “Plan B” shots that materialized when my original plan went awry due to weather, unexpected conditions (or my own stupidity).

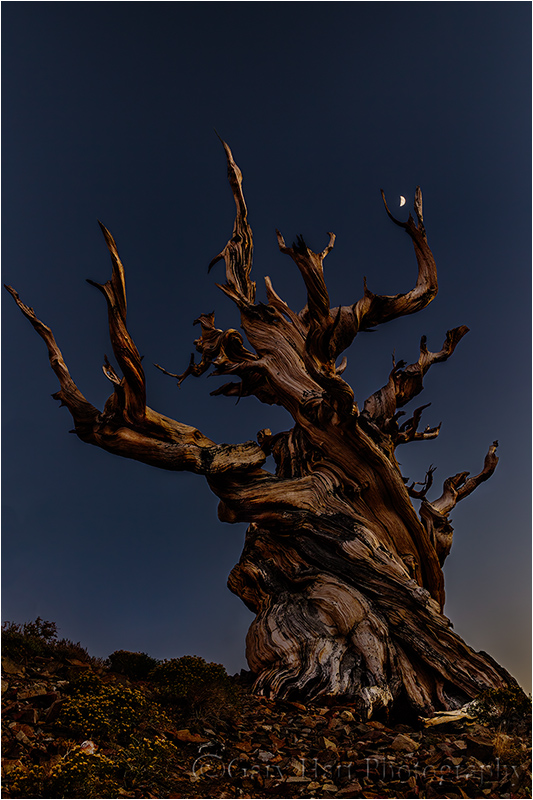

In my recent Eastern Sierra workshop, the clouds I always hope for never materialized. Whenever this happens I try to use the clear skies for additional night photography, but I’ve always been a little reluctant to keep my groups out late in the bristlecones because: 1) it’s colder than many are prepared for (late September or early October and above 10,000 feet); 2) it’s an hour drive back to the hotel the night before a very early sunrise departure. But this year, after spelling out the negatives, I gave my group the option of staying out to shoot the bristlecones beneath the stars. My plan was to arrange for a car (or two) to take back those who didn’t want to stay, but it turned out everyone was all-in.

In most of my trips I know exactly where the moon will be and when, but for this trip I hadn’t done my usual plotting—I knew it would be a 40 percent crescent dropping toward the western horizon after sunset, but hadn’t really factored the moon into my plans. But as we waited for the stars to come out, I watched moon begin to stand out against the darkening twilight and saw an opportunity I hadn’t counted on.

Moving back as far as I could to maximize my focal length (so the moon would be as large as possible in my frame) required scrambling on a fairly steep slope of extremely loose, sharp rock (while a false step wouldn’t have sent me plummeting to my death, it would certainly have sent me plummeting to my extreme discomfort). Next I moved laterally to align the moon with the tree, and dropped as low as possible to ensure that the tree would stand out entirely against the sky (rather than blending into the distant mountains). Wanting sharpness from the foreground rocks all the way to the moon, I dialed my aperture to f/16 and focused on the tree (the absolute most important thing to be sharp).

With the dynamic range separating the daylight-bright moon and the tree’s deep shadows was almost too much for my camera to handle, I gave the scene enough light to just slightly overexpose the moon, making the shadows as bright possible. Once I got the raw file on my computer at home, in Lightroom/Photoshop I pulled back the highlights enough to restore detail in the moon, and bumped the shadows slightly to pull out a little more detail there.

As you can see, even at 40mm, the moon is a tiny white dot in a much larger scene. But I’ve always felt that the moon’s emotional tug gives it much more visual weight than its size would imply. Without the moon this would be an nice but ordinary bristlecone image—for me, adding the moon sweetens the result significantly.

A Plan B gallery (images that weren’t my original goal)

Click an image for a lager view, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, Moon Tagged: bristlecone pines, Eastern Sierra, moon, nature photography, Photography

Small steps and giant leaps

Posted on July 20, 2014

Oak and Crescent, Sierra Foothills, California

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

320 mm

1.6 seconds

F/11

ISO 400

July, 1969

I turned 14 that month. I was into baseball, chess, AM radio, astronomy, and girls—not necessarily in that order. Of particular interest to me in 1969 was the impending moon landing, a milestone I’d been anticipating since tales of American aerospace engineering ingenuity and our heroic astronauts started headlining the Weekly Reader, and my teachers began gathering the class around a portable TV to watch the latest Gemini or Apollo launch or splashdown. If you remember the Sixties, you understand that the unifying buzz surrounding each Apollo mission briefly trumped the divisive tension surrounding headlines detailing Vietnam battles and demonstrations, the Civil Rights movement, and Communist paranoia. Unfortunately, without checking NASA’s schedule or asking for my input, my parents and three couples they knew from college decided mid-July 1969 would be the ideal time for our four families to join forces on a camping trip in the remote, television-free redwoods of Northern California. (“What could we possibly need a television for?”)

Apollo 11 was halfway to the moon when the Locher and Hinshaw families pulled up to our home in Berkeley (the Hardings, coming down from Eastern Washington, would meet us at the campground a couple of days later). The warm greetings exchanged by the adults were balanced by the cool introductions forced on the unfamiliar children. We departed the next morning, caravan style, our cars connected by woefully inadequate walkie-talkies that we’d almost certainly have been better off without (it had seemed like such a good idea at the time). I remember my dad keeping a safe distance behind Hinshaws, as he was convinced that their borrowed trailer, that seemed to veer randomly and completely independently of their car, would surely go careening into the woods on the next curve. But somehow our three-car parade pulled safely into Richardson’s Grove State Park late that afternoon.

In true sixties style, the three dads went immediately to work setting up campsites while the moms donned aprons and combined forces on a community spaghetti dinner. Meanwhile, the younger kids scattered to explore, while the four teens, having only recently met and being far too cool for exploration or anything remotely resembling play, disappeared into the woods, ostensibly on a firewood hunt. Instead, we ended up wandering pretty much aimlessly, kicking pinecones and occasionally stooping for a small branch or twig, just far enough from camp to avoid being drafted into more productive (and closely supervised) labor by the adults.

But just about the time we teens ran out of things not to do, we were relieved to be distracted by my little brother Jim, who had just rushed back into camp breathless, sheet-white, and alone. We couldn’t quite decipher his animated message to the parents, but when we saw our dads drop their tarps and tent poles and rush off in Jim’s tracks toward the nearby Eel River, we were (mildly) curious (to be interested in anything involving parents was also very not cool). So, with feigned indifference, the four of us started wandering in the general direction of the river until we (somehow) found ourselves peering down from the edge of a 50 foot, nearly vertical cliff at the river toward what was clearly the vortex of all the excitement. It was that instant when I think we all ceased being strangers.

The scene before us could have been from a bad slasher movie: Flat on the ground and unconscious (at the very least) was 11 year-old Paul Locher; sitting on a rock, stunned, with a stream of blood cascading from his forehead, was Paul’s 10 year-old brother John. As disturbing as this sight was, nothing could compare to seeing father Don Locher orbiting his injured sons, dazed and covered in blood. The rest of this memory is a blur of hysterics, sirens, rangers, and paramedics.

It wasn’t until the father and sons were whisked away to the small hospital in Garberville, about 10 miles away, that we were able to piece together what had happened. Apparently Paul and John, trying to blaze a shortcut to the river, miscalculated risk and had tumbled down the cliff. My brother at first thought they were messing with him, but when John showed him a rock covered with blood, he sprinted back to fetch the parents. Arriving at the point where the kids had gone over, the fathers made a quick plan. My dad and Larry Hinshaw would rush back to to summon help, and see if they could find a safer path down to the accident scene. Don would stay put and keep an eye on his sons. But shortly after my dad and Larry left, John had looked down at his brother cried, “Daddy, I can see his brains!” Hearing those words, Don panicked and did what any father would do—attempt to reach his boys. Thinking that a small shrub a short distance would make a viable handhold, Don took a small step in its direction, reached for and briefly grasped a branch, lost his grip, and tumbled head-over-heals down to the river.

After what seemed like days but was probably only an hour or two, we were relieved to learn that John needed no more than a few stitches; he was back in camp with us that night. Paul had faired slightly worse, with a concussion and a nasty cut behind his ear—the “brains” his brother had seen was ear cartilage. Paul spent the night in the hospital and was back with us by the time the Harding clan arrived the following afternoon. Don, however, wasn’t quite so fortunate. In addition to a severe concussion, he had opened up his head so completely that over 150 stitches were required to zip things back together. Though Don spent several days in the hospital, needless to say, we were all relieved by the understanding that it could have been much worse.

By Sunday, Don was feeling much better but was still a day or two from release to the dirt and fish guts of our four family campsite. Most of us had visited at one time or another, going in small, brief waves and respecting the hospital’s visiting hours. Nevertheless, there was another priority that had gone unspoken in the first few days following the accident came to prominence with the realization that Don would be fine. I can’t say who first recognized the opportunity, but I’m guessing that Larry Hinshaw had something to do with convincing the nursing staff to look the other way when Don was suddenly host to 20 simultaneous visitors that night. Whatever magic was worked, I’ll never spending that Sunday evening, July 20, 1969, shoehorned into a tiny hospital room, sharing a tiny black-and-white television screen with 20 pairs of eyes, witnessing history.

Besides my parents and two brothers, the rest of the crew that night I’d only met just a few days earlier, but I can still name every single one of them. The relationships formed that week continue to this day. And so do the stories, which, like this story, are filled with some of the greatest joy I’ve ever experienced, and also with some of the greatest tragedy. But it’s this story in particular, the catalyst for all the stories that follow, that explains why the words, “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” have a very personal significance for me.

Today it’s hard for me to look at the moon without remembering that hospital room and the emotional events that enabled me to witness Neil Armstrong’s historic first steps with those special people. As a child of the Sixties who very closely followed all of the milestones and tragedies leading up to that moment, I couldn’t help but wonder while assembling the images for the gallery below about that week’s role in shaping who I am and what I do today.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A lunar gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: crescent moon, full moon, Moon Tagged: crescent moon, full moon, moon, Photography

Another day, another moonrise

Posted on May 16, 2014

* * * * *

Previously on Eloquent Nature

* * * * *

May 13, 2014

After seeing the images captured by the people in my group followed me on Monday evening, during the next day’s image review session a few in my workshop group asked if we could go back up to Glacier Point for sunset that night. I did a quick-and-dirty plotting and showed them about where the moon would be at sunset (I usually tend to be more OCD about precision when plotting the moon, but “about” was good enough for our purposes), explaining that I’d planned to photograph the moonrise from a different spot that night, but I’d be willing to forego that shoot in favor of a Glacier Point reprise if that’s what everyone preferred. But, I warned, tonight would also be our only opportunity to photograph the Lower Yosemite Fall moonbow—if we drive up to Glacier Point, we probably won’t make it back down to the valley for the moonbow shoot until after 9:00. While that would be plenty early enough for the moonbow, it would mean we’d have been going from before 6:00 a.m. until about 11:00 p.m. But the vote was unanimous, so back up we went.

I love plotting a moonrise. I’ve been doing it for a long time—when done right there’s no mystery to the time and location of the moon’s arrival, but there’s just something thrilling about the watching the moon peek above the horizon. (Not to mention the (unjustified) awe my workshop groups express when it happens exactly when and where I’d predicted.) When we considering altering the schedule I’d them that we’d see the at around 7:40, give or take five minutes, just a little to the left of Mt. Starr King. And sure enough, at 7:36 there it was, a white wafer poking from behind the left flank of Gray Peak (the left-most peak in the above image).

Full disclosure

Before you decide that my moon prediction makes me some kind of photography savant, I should probably explain why the camera I used to photograph this scene was my backup, 1DS Mark III, and not my primary, 5D Mark III. (The 1DS III is still a great camera, it’s just seven-year old technology.) That would be because, genius that I am, my camera bag, complete with camera, lenses, tripod, and filters was still back at the hotel. Fortunately, knowing the way workshops force me out of my routine (leading to a long history of forgotten tripods and cameras abandoned by the roadside), I always have a backup tripod and camera bag with my backup camera and a lens or two in the back of my car. Which is how my 1DS III and 100-400 lens (which I find too bulky and awkward for everyday use) were back there and ready for action. What I didn’t have was my remote release and graduated neutral density filters, essential to my twilight moonrise workflow. Fortunately, one of the workshop students took pity on me and loaned me a GND she wouldn’t be using (thanks, Lynda!); I turned on the 2-second timer to eliminate shutter-press vibrations.

But anyway…

As cool as the moon’s appearance was, the best full moonrise photography doesn’t come until a little later. From about five minutes before sunset, when the sky has darkened enough for the daylight-bright moon stand out, until about ten minutes after sunrise, when the foreground has darkened too much to be captured with a single frame (even with the use of a GND), is my moonrise “prime time.”

But even though the best stuff wouldn’t come until later, I photographed the moonrise from its first appearance, varying my composition as much as the 100-400 lens would allow—getting Half Dome in the frame was out of the question, but since I’d already covered that the night before, this was going to be more of a telephoto shoot anyway. Everything was at infinity, but in this case I opted for f8 (f11 is my usual “default” f-stop) and ISO 400 because, given the weight of the 1DSIII and 100-400 lens, I was a little concerned about my tripod’s ability to dampen completely after 2-seconds. By the time the light got really good and the sky started to pink-up, I was quite familiar with all the compositions and was able to cycle through them very efficiently.

By about 8:15 we were hustling back down the mountain to our date with the moonbow. But that’s a story for a different day….

Join me as we do it all over again in next year’s Yosemite Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop

Category: full moon, Glacier Point, Moon, Yosemite Tagged: full moon, Glacier Point, moon, Mt. Starr King, Photography, Yosemite

Glacier Point moonrise

Posted on May 13, 2014

May 12, 2014

I’ve been in Yosemite for my annual Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop. Monday night I took the group to Glacier Point for sunset—an unexpected benefit of California’s drought that allowed Glacier Point Road to open weeks earlier than normal. I knew a nearly full moon would be rising above the Sierra crest that evening, but figured that since it would be so far south, we wouldn’t be able to do a lot with it. But when I arrived Glacier Point and saw the moon rising above Mt. Starr King, I realized that shifting slightly south, away from the popular Glacier Point View, might just allow us to include the moon and Half Dome in a wide shot. Hmmm. But because we had people in the group who had never been to Glacier Point, I decided now was not the time for exploration.

As always happens at Glacier Point on these predominantly clear evenings, the light on Half Dome warmed beautifully as the sun dropped to the horizon behind us. Organizing an expansive landscape into a coherent image can be difficult, especially for first timer visitors. But as I moved between the students positioned along the rail, it seemed that all were doing fine and realized that my greatest value at the moment was to stay out of the way. Appreciating the view, I just couldn’t get that moon, blocked by trees from our vantage point, out of my mind.

When a couple of people in the group asked why I wasn’t shooting (it always makes them nervous when the leader is looking at the same view they’re photographing but shows no interest in shooting), I told them I was simply enjoying the view (quite true). But when someone asked if I had any suggestions for something different, my ears perked up. I told them if I were to be shooting, I’d go back up the trail a hundred yards or so to see if I could get around the trees and find something that included the moon.

When several people sounded interested, I warned them that there’s no guarantee we’d find anything photo-worthy, and relocating so close to sunset would risk missing the show entirely. Much to my delight, a couple of people said, “Let’s do it,” and that was all I needed to hear. I told Don (Don Smith, who’s assisting this workshop—for those who haven’t been paying attention, Don assists some of my workshops, I assist some of Don’s, and we do a few workshops as equal collaborations) that I was taking a few people back up the trail and off we went.

I ended up with five (nearly half the group) at the view just below the Glacier Point geology exhibit. I chose this spot for its open view, and for the way it allowed us to frame the scene with Half Dome on the left, triangular Mt. Starr King and the moon on the right, and Nevada and Vernal Falls in the center. With a couple of trees and dark granite for the foreground, the scene couldn’t have been more ideal if I’d have assembled it myself.

I took out my 16-35 and composed this scene that pretty much seemed to frame itself. Even though I had subjects ranging from the fairly close foreground the the extremely distant background, at 21mm I knew I’d have enough depth of field at f11. I used live view to focus on the foreground tree, more than distant enough to ensure sharpness throughout my frame.

While I almost always rely on my RGB histogram to check my exposure, my general exposure technique when photographing a full moon in twilight is to forego the histogram and concentrate on the moon. As far as I’m concerned, a shot is a failure if the moon’s highlights are blown (a white disk), but since the moon is such a tiny part of the frame, it barely (if at all) registers on the histogram. What does register is the blinking highlight alert that signals overexposed highlights. When the foreground is dark, I’ll continue pushing my exposure up until the moon just starts to blink (not the entire disk, just the brightest spots). I know from experience that I can recover these blown highlights in post processing. I also know that this is the most light I can give the scene, because the moon’s brightness won’t change as the foreground darkens. (While I don’t blend images, for anyone so inclined it’s quite simple to take two frames, one exposed for the foreground and the other exposed for the moon, and combine the two in Photoshop.) In this case I spot metered on the foreground to ensure enough light to retain color and detail in the rapidly darkening shadows, then used a Singh-Ray 2-stop hard graduated neutral density filter to hold back the sky and (especially) protect against blowing the moon.

* * * *

About this scene

This is the view looking east from near Glacier Point. From left to right: Cloud’s Rest (just behind Half Dome), Half Dome, Vernal Fall (below—the white water beneath Vernal Fall is cascades on the Merced River), Nevada Fall (above), Mt. Starr King (triangle shaped peak).

Join me as we do it all over again in next year’s Yosemite Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop

Category: full moon, Glacier Point, Half Dome, Moon, Nevada Fall, Vernal Fall, Yosemite Tagged: full moon, Glacier Point, Half Dome, moon, Nevada Fall, Photography, Vernal Fall, Yosemite

Four sunsets, part four: Saving the best for last

Posted on February 23, 2014

Twilight Magic, Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

3 2/3 seconds

F/11.0

ISO 400

45 mm

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

- Read the second in the series here: Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

- Read the third in the series here: Four sunsets, part three: A marvelous night for a moondance

What I love most about photography is its ability to surprise me. Case in point: the final sunset of my recent Yosemite Horsetail Fall workshop, which delivered just one surprise after another.

I’d told my group that we’d get to photograph another moonrise on our last evening, but only if the clouds cooperated. And as the afternoon wore on, it seemed that the clouds that had cooperated so wonderfully all week wouldn’t be on our side tonight. Assembling everyone on the sloped granite above Tunnel View, I eyed the thin (and shrinking) strip of blue sky on the horizon above Half Dome and checked my watch: 5:10—in about fifteen minutes (less than ten minutes before sunset), with no clouds we’d see a full moon poke into view between Half Dome and Sentinel Dome. But our vantage point gave me a clear view of the clouds racing in that direction and our prospects weren’t good. Rather than stress (much), I stayed philosophical: We’d already had three fantastic sunset shoots, expecting a fourth would be downright greedy.

Nevertheless, it was fun to watch the clouds sprint across the sky and pile up behind Half Dome, changing the scene by the minute. Waiting there, I had thoughts about the throngs gathered on the valley floor, hoping (praying) for Horsetail Fall to light up. My group had been lucky on our first two sunsets, but tonight there’d been no sign of sunlight for at least thirty minutes, and with the cloud machine working overtime behind us, I was pretty certain the Horsetail crowd was in for disappointment.

Anticipating a moonrise, I’d gone up our vantage point with just my tripod, 5DIII, and 100-400 lens. Knowing exactly where the moon would appear, my composition was set well in advance—tight, with Half Dome on the far left and the moonrise point on the far right. But without the moon, I realized that the best shots would likely be wide, so I zipped back to the car and returned with another tripod (doesn’t everyone carry two?), my 1DSIII, and my 24-105. Sitting on the (cold) granite, a tripod on my left and my right, I quickly composed a wide shot with my new setup and resumed my vigilance.

By 5:25 I’d stopped watching the incoming clouds, which were streaming in faster than ever, and turned my focus to the moon’s ground-zero, willing the clouds to part for its arrival. At exactly 5:27 and as if by magic, the white glow of moon’s leading edge burned through the trees downslope from Sentinel Dome. I did a double-take—it was as if the moon had pushed the cloud curtain up and slipped beneath. I shouted, “There it is!” and the furious clicking commenced. We ended with about sixty seconds of moonrise, just long enough for the moon to balance atop the trees, before the clouds settled back into place and snuffed it out.

But the surprises had only just begun. While the whole group still buzzed about the moon, I noticed a faint glow on El Capitan. Not quite believing it (and not wanting to jinx anything), I kept my mouth shut and looked closer. But when the glow persisted, I had to point it out, if for no other reason than confirmation that I wasn’t hallucinating. Within seconds all doubts were dispelled as El Capitan exploded with light from top to bottom. So sudden and intense was the light that I’m surprised we didn’t hear the roar from the Horsetail Fall contingent in the valley below us. And rather than fade, as it often does, the light intensified, warming over the next couple of minutes from amber to orange to red. Soon the color deepened to an electric magenta and spread across the sky and all those clouds I’d been silently cursing just a few minutes earlier became allies, catching the color and reflecting it back to the entire visible world.

Giddy about the show, and focused on my two cameras, I’d long given the moon up for dead. So imagine my surprise when, just as the color reached a crescendo, there the moon was, burning through a translucent veil of clouds. So expansive was the scene that a telephoto couldn’t do it justice, so all of my images following the moon’s resurrection were captured with my 5DIII and 24-105. Exposure became trickier by the minute in the advancing darkness, and eventually, pulling detail from the valley without completely blowing out the moon required a 2-stop hard graduated neutral density filter.

Honestly, this was one of those moments in nature that no camera can do justice. I did my best to come find compositions that captured the majesty of Yosemite Valley, the vivid sky and the way it tinted the entire scene, and that Lazarus moon. But take my word for it, you just had to be there….

* * * *

Four Sunsets

Join me next February when we do it all over again

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, Moon, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, moon, Photography, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About