Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Looking on the bright side

Posted on July 1, 2013

There has been a lot of photographer hand wringing in the wake of Adobe’s Creative Cloud power play. I know of very few photographers, amateur or pro, who are happy to suddenly be forced to pre-pay for Photoshop upgrades they’ve always been able to evaluate before deciding they’re worth purchase. Now our choices are between biting the bullet and signing up for Adobe’s rental plan (“You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave”), or hopping off the Photoshop upgrade train.

Applying the most optimistic spin possible, my hope is that Adobe’s new Photoshop rental paradigm forces photographers to evaluate their Photoshop habit and (fingers crossed) realize that having the latest processing tool isn’t as essential as they might think. I can’t help but flash-back to my color transparency days, when I had no idea at capture whether I’d squeezed the scene’s light in the narrow dynamic range (and hadn’t somehow included my thumb), knowing that I’d be pretty much stuck with whatever came back from the lab. Compare that to today’s instant feedback and the processing magic possible with raw capture and Lightroom/Photoshop. Pretty cool. I mean, in my film days if someone had offered me all the capabilities of, say, Photoshop CS2 for the rest of my photography life, I’d have been thrilled. But somehow we became hooked, and no matter what the current processing capabilities are, we can’t live without the next great thing. While progress is wonderful, I’m afraid our upgrade addiction has created many photographers who care more about processing than capture.

So. Let me suggest that do yourself a favor and take a deep breath before committing your photography future to Adobe’s whims. Consider this an opportunity to use the time you would have spent learning the next processing tool or technique to work instead on your photography. What a concept. For example, if you can’t get your exposure to within 1/3 of a stop of where it should be with the first click, you and your camera have work to do. If you can’t determine the aperture and focus point that gives you the desired depth of field (or you can’t determine when the desired depth of field isn’t possible), you and your camera have work to do. And most importantly, no matter how strong you are with exposure and hyperfocal focus now, your vision and composition skills always have room to grow.

Am I opposed to Photoshop? Absolutely not. Nor am I suggesting that you shouldn’t commit to ACC (and I can’t even say that I’ll never do it). I just think that before committing to ACC, you understand that once you do, using anything above Photoshop CS6 means paying Adobe every month for the rest of your life, regardless of features, quality, and service. And the alternative, to stay with CS6, might just free you up to spend more time taking pictures. I can think of worse things.

About this image

One spring afternoon a few years ago, instead of sitting at my computer working on images, I tossed my camera bag in the car and headed for the hills. There was nothing particularly compelling about the conditions, I just wanted to take pictures. I ended up on a narrow country road near Plymouth, south and east of Sacramento. With sunset approaching, I picked these trees to frame the setting sun. This ordinary scene on an ordinary evening became an image that makes me very happy, something that never would have happened had I not just gone out and looked. It’s what photographers do.

Category: Oak trees, Sierra foothills Tagged: Photography, photoshop

Where did you get those shoes?: Storytelling for landscape photographers

Posted on June 25, 2013

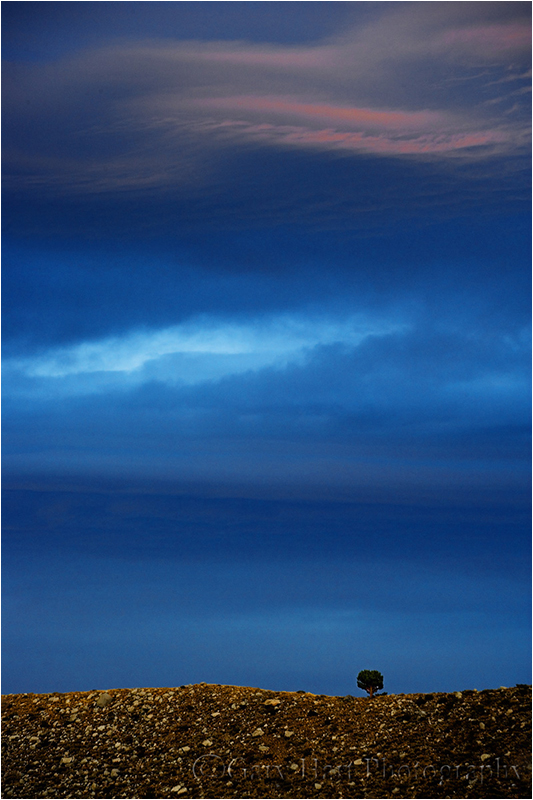

Tree at Sunset, McGee Creek Canyon, Eastern Sierra

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

1/40 second

F/7.1

ISO 400

126 mm

Let’s have a show of hands: How many of you have been advised at some point in the course of your photographic journey to “tell a story with your images”? Okay, now how many of you actually have a clue as to what that actually means? That’s what I thought. Many photographers, with the best of intentions, parrot the “tell a story” advice simply because it sounded good when they heard it, but when pressed further, are unable to elaborate.

Telling a story is more easily accomplished in the photographic forms that allow photographers to arrange scenes and light to suit their objective (an art in itself), or journalistic photography intended to distill the the essence of an instant in time: a homeless man feeding his dog, dead fish floating in the shadow of belching smokestacks, or a wide-receiver spiking a football in the end zone.

This isn’t to say that landscape photographers can’t tell stories with our images, or that we shouldn’t try. Nor does it mean that one photographic form is inherently more or less creative than another. It just means that the rules, objectives, advantages, and limitations are different from form to form. Nevertheless, simply advising a landscape photographer to tell a story with her images is kind of like a coach telling a pitcher to throw strikes, or a teacher instructing a student to spell better. Okay, fine—now what?

Finding the narrative

First, let’s agree on a definition of “story.” A quick dictionary check reveals this: A story is “a narrative, either true or fictitious … designed to interest, amuse, or instruct….” That works.

The narrative part is motion. Your pictures need it. Narrative motion isn’t the visual motion of the eyes through the frame (also important), it’s a connection that pulls a viewer into a frame and compels him to stay. While narrative motion happens organically in media consumed over time, such as a novel or a movie, it can only be implied in a still photograph. And unlike the arranged or journalistic photography forms I mentioned above, landscape photographers are tasked with reproducing a static world as we find it—another straightjacket on our narrative options. But without some form of narrative motion, we’re at a dead end story-wise. What’s a photographer to do?

Photography as art

Every art form succeeds more for what happens in its consumer’s mind than for what it delivers to the consumer’s senses. Again: Every art form succeeds more for what happens in its consumer’s mind than for what it delivers to the consumer’s senses. A song that doesn’t evoke emotion, or a novel that doesn’t paint mental pictures, is soon forgotten. And just as readers of fiction unconsciously fill-in the visual blanks with their own interpretation of a scene, viewers of a landscape image will fill-in the narrative blanks with the personal stories the image inspires.

Of course the story we’re creating isn’t a literal, “Once upon a time” or “It was a dark and stormy night” (much more effective in photography than literature, I might add) story. Instead, the image we make must connect with our viewer’s story to touch an aspect of their world: revive a fond memory, provide fresh insight into a familiar subject, inspire vicarious travel, to name just a few possible connections. If we offer images that tap these connections, we’ve given our image’s viewers a reason to enter, a reason to stay, and a reason to return. And most important, we’ve given them a catalyst for their internal narrative. Bingo.

Shoot what you love

Think about your favorite novels. While they might be quite different, I suspect one common denominator is a protagonist to whom you can relate. I’m not suggesting that immediately upon finishing that book you hopped on a raft down the Mississippi River, or ran out to have a dragon tattooed on your back, but in some way you likely found some personal connection to Huckleberry Finn or Lisbeth Salander that kept you engaged. And the better that connection, the faster the pages turned.

And so it is with photography: Our viewers are looking for a connection, a sense that there’s a piece of the photographer in the frame. Because we can’t possibly know what personal strings our images might tug in others, and because those strings will vary from viewer to viewer, our best opportunity for igniting their story comes when we share our own relationship with a scene.

What? Didn’t I just say that it’s the viewer’s story we’re after? Well, yes—but really what needs to happen is the viewer’s sense of connection between our story and hers. If you focus on photographing the scenes that most move you, those scenes (large or small) that might prompt you to nudge a loved-one and say, “Oooh, look at that!,” the greater your chance of establishing each viewer’s sense of connection. Whether you’re drawn to mountains, crashing surf, delicate wildflowers, or prickly cactus, that’s where you’ll find your best images.

But what about the shoes?

The cool thing is that your viewer doesn’t need to understand your story; he just needs to be confident that there is indeed a story. That’s usually accomplished by avoiding cliché and offering something fresh (I know, easier said than done). For some reason this makes me think of Steely Dan lyrics, which rarely made sense to me, but they were always fresh and I never for a second doubted that they did indeed (somehow) make sense. In other words, rather than becoming a distraction, Steely Dan’s lyrics were a source of intrigue that pulled me in and held me. So when I hear:

I stepped up on the platform

The man gave me the news

He said, You must be joking son

Where did you get those shoes?

I’m not bewildered, I’m intrigued. Donald Fagen’s lyrics aren’t trying to tap my truth, they simply reflect his truth (whatever that might be). And even though I have no idea what he’s talking about, the vivid mental picture Fagen’s lyrics conjure (which may be entirely different, but no more or less valid, than your mental picture) allows me to feel a connection. You, on the other hand, may feel absolutely nothing listening to “Pretzel Logic,” while “I Want To Put On My My My My My Boogie Shoes” might give you goosebumps for KC and the Sunshine Band. Different strokes….

Returning from the abstract to put all this into photographic terms, the more your images are true the world as it resonates with you, and the less you pander to what you think others want to see, the greater the chance your viewer’s story will connect with yours.

The story of this image

My own story of this image involved a frantic rush to capture a beautiful but rapidly fading sunset. I was with my brother on a dirt road in the Eastern Sierra. I’d been on this road many times and knew this tree well. Despite its rather ordinary appearance, the tree’s solitary perch atop a barren, rocky ridge had always intrigued me. I’ve always longed for a home with a sweeping view, and envied this tree’s perpetual 360 view of the Sierra crest to the west, the White Mountains to the east, and Crowley Lake below.

As the sunset started to materialize that evening, I realized that we were close enough that I might be able to include the tree in the sunset shoot. We hustled my truck back down the road, pulling into to a wide spot beneath the ridge several minutes after the best color had faded. Jay, who had no personal connection to “my” tree, stayed in the truck while I sprinted along the road with my camera and tripod until my position aligned the tree with the final, rippled vestiges of sunset. I only clicked a couple of frames, slightly underexposed to hold the color. (The slight blue cast is the color of the twilight light.)

That’s my story, and while it’s personally satisfying, I have no illusions that any of that comes across in the image. I’ve displayed this print in many shows and watched people walk right by without breaking stride. But I’ve also been pleased to watch many people stop, linger, and return. While I have no idea what “story” this image taps for them—solitude? conquest? perseverance?—I don’t think it really matters.

Category: Eastern Sierra, How-to, McGee Creek, Photography Tagged: Eastern Sierra, Photography, storytelling

Adobe plays Monopoly with your photos (required reading for all Photoshop users, present and future)

Posted on June 17, 2013

Storm brewing

Adobe recently announced the new Adobe Creative Cloud paradigm for its Creative Suite software (Photoshop, Illustrator, Dreamweaver, et al). While Photoshop is an essential part of my workflow, I’m not a power user and earn no income from Photoshop training, so I hadn’t really given this change a lot of thought. My plan has always been to simply stick with my current Photoshop CS6, which I’m quite happy with, and to stay out of the fray. That was before Michael Frye’s recent blog post, and the comments it generated, started me thinking a little deeper about the ramifications of Adobe’s change.

Once upon a time

Under the pricing model replaced Adobe replaced with ACC, Photoshop (I’m going to limit my comments to Photoshop, which is all that matters to me and most of my readers) has been updated every year or two (closer to two years than one); current users, after an initial $600+ purchase landed them on the Photoshop carousel, could upgrade to the latest version for an upgrade fee of $200 or so. While the initial price and the upgrade fee were far more than I typically pay for software and upgrades, not only do I need Photoshop, it’s amazing software that I’ve always felt was worth the price.

Send in the cloud

Enter Adobe Creative Cloud. Starting immediately, all subsequent Photoshop versions will be available on a subscription-only basis: $20/month for Photoshop only (because I’m looking more at ACC’s long-term ramifications, I’m ignoring the introductory, twelve-month, Photoshop for $10/month lure Adobe is offering); $50/month for the entire suite (plus a few other subscription options depending on use and current license status). For your ACC subscription you get lots of features of dubious value, free cloud storage (limited value for most), and, most importantly, instant access to new Photoshop features.

New users (surely there are still a few photographers out there not using Photoshop yet), rather than having to shell out the initial $600 (or whatever—there are lots of special offers that can reduce the Photoshop entry price somewhat), simply have to start a subscription: Score one for new users. Existing Photoshop users who paid their $600 initiation and have loyally contributed the $200 sub-annual upgrade dues, have gotten nothing but a shrug and an, “Oh well,” from Adobe. Score one for Adobe. While this doesn’t seem like a particularly great way to treat loyal customers, I haven’t been particularly critical of this aspect of the change because I always felt each version of Photoshop gave me my money’s worth.

What’s all the grumbling about?

ACC has inspired lots of complaints that would be easy to write it off as the standard grumbling that happens whenever an industry leader changes something (interface, security, pricing, etc.). And some Adobe Creative Suite multi-product users are singing the praises of Adobe’s move, pointing out that it will actually save them money in the long run. So what’s the problem?

Most of the praise and complaints about ACC are misguided and shortsighted. It’s true that ACC will cost most casual users more in the long run, with little added benefit (over continuing the current upgrade-fee paradigm). And even for many more serious users, the extra cost won’t add much benefit. For example, while I haven’t missed an upgrade in many years, I rarely upgrade immediately upon availability, and am even slower to incorporate the latest features. Generously assuming an upgrade outlay of $200 of every eighteen months under the current scheme (the historic average isn’t that frequent), at $20/month I’d be paying Adobe $360 every year and a half, $160 more than I currently pay. Since the new features are rarely an immediate game changer for me, and all the extra ACC “perks” are of zero interest, I see no way paying more money for ACC can be better than the current arrangement. Nevertheless, if Adobe had simply increased its upgrade fees, I’d have been less than thrilled but would have continued buying upgrades with little complaint.

On the other hand, those who use multiple ACC products and have a limited budget must be thrilled with the savings: the more ACC products you use, the more money you’ll save. And Photographers who must have the latest feature the instant it’s available will probably be very happy with the opportunity to fulfill their first-kid-on-the-block urges because they won’t need to wait a year or two for the next new Photoshop version.

It’s not just a game

Monopoly: exclusive control of a commodity or service in a particular market, or a control that makes possible the manipulation of prices.

Adobe Photoshop has held a monopoly on serious photo processing for years (and years). After pretty much saturating the market for new Photoshop users, Photoshop’s potential for growth more or less flatlined, making upgrades Adobe’s revenue bread-and-butter. But, since users could decide whether or not to spring for the latest upgrade based on its benefits over the prior version, Adobe was actually competing with itself only—in other words, to entice users to shell out $200 for the new version, Adobe wasn’t battling outside competition, the only competition they had to outdo was themselves (their previous version).

I suspect Adobe became a little tired of this (after all, what good is a monopoly if you can’t kick back with your feet on your desk, flicking cigar ashes on the floor?). Enter the cloud. While Adobe wasn’t at risk of losing money under the old model, it just found an opportunity to make more money. That’s what capitalism is all about. The problem is, capitalism starts to fall apart when monopolistic power supresses competition. And with no competition, Adobe has much less incentive to please its users. Since Adobe had no other competition to eliminate, they changed the rules to remove themselves from the equation—bingo, instant monopoly. If you’re not convinced that’s what happened here, ask yourself whether Adobe would have attempted something like this if its customers had any other options. And why they haven’t allowed us to choose between the old model and the new model.

Under the old model, Adobe had to deliver something of value before we gave them our money—if we didn’t think the latest version was worth the upgrade fee, we could simply wait until the next one (or the one after that). Now, under ACC, Adobe asks us to pay today and trust them to continue providing value in the form of performance improvements, reasonable pricing, and (especially) new tools. And if at any point we decide they’re not giving us value, withholding our money not only stops future improvements from landing on our computer, it sends us all the way back to where we are today (CS6).

Compounding the problem is the likelihood that improvements will, sooner or later, render new Photoshop files incompatible with CS6. Perhaps future ACC features will be so significant that there’s no avoiding backward compatibility limitations as the versions diverge; but a cynic might argue that backward incompatibility is also a smart business strategy that would very effectively lock ACC users into perpetual rent payment. It would also insulate Adobe against a mass exodus should they, let’s say, decide to increase the rent. And when the day comes when you can’t take your ACC-processed images elsewhere, you’re at Adobe’s mercy.

From Adobe’s perspective, ACC is genius, its long term profit potential limited mostly by their ability to convince the world that it’s actually in Photoshop users’ best interest. But I’m afraid that, in addition to the simple cost hits cited earlier (again, not a huge deal as far as I’m concerned), ACC is an opportunity for Adobe to get fat and lazy. Even if that’s not in their plan, there’s nothing like competition to inspire innovation, service, and reasonable prices. And there’s nothing like a monopoly to suppress all those inconvenient revenue drains. So, even if you believe that Adobe is an inherently good corporation that bases all decisions not on what will maximize its revenue but rather on what will most benefit users, removing the need to compete (even if it was only with itself) eliminates the motivation that has spurred them to consistently amaze us with the great and unexpected.

Meet the new boss

Should you allow Adobe to become your landlord? That’s your call; the answer isn’t absolute and depends on your circumstances and priorities. But you should at least approach the decision with full understanding of the longterm ramifications. Moving out of your reliable, fully paid for image processing home and into a flashy new image processing rental means trusting that your Photoshop landlord will be a benevolent monopolist (not just today, but tomorrow and the next day too), that they’ll continue to be at least as innovative and timely with fixes and improvements as they’ve ever been, even if they don’t have to. Because once you’re in, you’re in.

Five years from now, if you realize that Adobe has had its development feet on the desk for a while, jacking the rent while the cigar ashes accumulate on the floor, you’ll have two options: continue paying rent hoping that they’ll eventually fix the plumbing and add that new pool and gym you’ve been waiting for; or, simply stop paying rent, get evicted, and move back into to that place where you used to live (that hasn’t been worked on in five years). Oh, and you won’t be able to take any of your new stuff with you either.

* * * *

I chose the image at the top of this post because it has a cloud. (Genius!)

Category: Photography, Poppies, Sierra foothills, wildflowers Tagged: adobe, Photography, photoshop

Nature is only as random as our ability to understand it

Posted on June 11, 2013

Louis Pasteur said that chance favors the prepared mind. It was one of Ansel Adams’ favorite quotes. But, as appropriate as the quote is, I’m sure Adams cited Pasteur only after enduring countless “Wow, you were so lucky to be there for that” reactions.

To the casual observer, nature’s wonders do indeed feel random. Who doesn’t feel lucky when a full moon pops over the mountains just as the monotonous highway bends east, or when dirty snow and bare trees are suddenly glazed in white by an unexpected snowstorm? (Or when Yosemite Valley is suddenly framed by an arcing double rainbow?) But there’s nothing random about any of these phenomena. Some natural phenomena can be predicted with absolute precision—for example, it’s easy to pinpoint the position and phase of the moon for any location and time, past or future. And while weather can sometimes (usually?) appear random, every weather condition, from temperature to the most violent storms and purest blue skies, is a precise function of atmospheric conditions, ocean currents, and terrain; we perceive weather as random only because its complexity overwhelms our current capabilities.

Nature photographers should feel blessed by these natural wonders over which we have no control, but our good fortune is not random. By taking the time to understand our subjects and study our environment, we do our best to anticipate image-worthy events. While we can never guarantee that the sky will be clear enough to reveal the rising moon we counted on, or that the predicted convergence of moisture, temperature, and barometric pressure will manifest to transform our world from crusty brown to pristine white (or that the setting sun will find the perfect path to the falling rain), we can put ourselves in position to be there when it happens.

None of this stuff makes me unique—though we all approach our photography in our own way, most successful nature photographers do everything they can to minimize the randomness in our efforts, to maximize the chance for “special.” My own path was fairly organic. My entire life, beginning long before my first camera, I’ve been drawn to science, to the how and why of nature. As a child I devoured books by Herbert S. Zim and Isaac Azimov (he wasn’t just a science fiction writer). In school I took every possible astronomy, geology, meteorology class. I even started college as an astronomy major, then geology, before the (necessary) quantification of the concepts I loved so much threatened to sap my passion (that is, I couldn’t handle the math beyond calculus). Fortunately my passion survived and I’ve been able to find a career that rewards me for understanding and anticipating natural phenomena. (It hardly seems like work.)

About this image

Which brings me to today’s Yosemite Valley rainbow image, an incredible stroke of good fortune that I (proudly) take credit for anticipating. This was a May evening a few years ago. May is usually the beginning of California’s interminable blue sky summer, but this year a persistent low pressure system that had set up camp off the coast pumped daily impulses of moisture into Northern California. I was in Yosemite to meet a private workshop customer and his girlfriend for dinner so we could plan the following day’s photo tour of the park. That afternoon’s drive from home had been a mixture of sun and showers; I entered Yosemite Valley in the midst of a steady rain that had been splashing my windshield for at least thirty minutes. But despite clinging rainclouds that obscured the surrounding granite walls, I knew the broken sky I’d recently driven through was headed this way and would probably arrive before sunset, about two hours away—and with that clearing would come the potential for openings that could allow sunlight to reach the still falling rain. With the sun already low and dropping, and its angle pointing any Tunnel View shadow in the direction of Yosemite Valley, I had the potential for all the rainbow recipe ingredients.

But of course I had dinner plans, and no phone number to reach my customers. So I beelined to Yosemite Lodge to meet them as planned, plotting my sales pitch the entire way. I was pleased to find them waiting when I arrived—while in my mind I was jumping up and down, pointing and shouting (“Rainbow! Soon! Hurry!”), I maintained the illusion of calmness through our introductions, then explained as cooly as possible that there was a chance for a rainbow, if they were interested. Fortunately they were open to the change of plans and I wasn’t forced to resort to begging.

On the twenty minute drive back to Tunnel View I’d calmed enough to remind myself that we could very well be chasing wild geese and did my best to moderate their expectations, explaining that a rainbow is far from a sure thing, and that what we’re doing is merely putting ourselves in position in the event that does happen.

At Tunnel View the rain was still falling, but I could see signs of clearing to the west. So far, so good. I guided my customers to my favorite Tunnel View vantage point, above the parking lot and away from the crowds, where we sat on the granite in the rain and waited. Despite their positive attitude, as the cold and wet began to seep in, it dawned on me that convincing new customers to skip dinner to sit in the rain isn’t the most sound business strategy.

The view of had opened considerably from what it had been when I first pulled into the valley, so I encouraged them to go ahead and shoot, rainbow or not. I really can’t remember how long we waited—long enough to get pretty soaked—before a shaft of sunlight broke through to illuminate the rain falling along the north rim of the valley, for about five minutes painting a vivid partial double rainbow in front of El Capitan and disappearing into the clouds above Half Dome. Yay! While this wasn’t a complete rainbow (only one pot of gold), it was definitely the nicest rainbow I’d ever seen at Tunnel View and we clicked without a break until the rain stopped and the rainbow faded.

When the show was over we just sat and marveled at the view, giddy about our good fortune, completely oblivious to the dark cloud approaching from behind. As quickly as the rain had stopped a few minutes earlier, it returned, this time with a vengeance, coming down in diagonal sheets (visible across the top of the frame above). Behind us and out of sight the sun had almost completed its journey to the horizon and, rather than being blocked by clouds as it had been earlier, was able to slide its final rays beneath them to completely illuminate the rain falling across the valley’s breadth. The rainbow appeared almost immediately, intensifying to quickly become a double bow connecting Yosemite Valley’s north and south walls. It lasted so long that I actually started running out of compositions.

We had a great day the next day, but nice as it was, the photography was a bit anticlimactic. Much like starting the Fourth of July fireworks show with the “grand finale” extravaganza, I realized that it would have been nice to have arranged for the rainbow to appear at the end of our session. Back to the drawing board.

Learn a more about rainbows and how to photograph them.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, rainbow, Sentinel Dome Tagged: double rainbow, Photography, Rainbow, Yosemite

It’s geek to me

Posted on June 2, 2013

While it would be silly to pretend that digital photography hasn’t changed my photographic life, at heart I’m simply a film shooter with a digital camera. If you read my writings or have attended my workshops, you’ve no doubt heard me say that photography, at any level, must be a source of pleasure. How each of us derives our pleasure varies greatly, from what we shoot, to how we shoot, to what we do with (to) our images after we shoot them. From what I’ve observed, many photographers relish their time at the computer, scrutinizing corner sharpness, high ISO shadow noise, and working Photoshop magic to take their images to the next level. I’ve always been so much happier outside, simply enjoying, and making pictures of, the things I love—the computer, while necessary, always feels too much like work.

That’s probably because I came to photography as a career after twenty-plus years in the high-tech industry. During those twenty years my time with my camera was pure pleasure, a creative escape from the technical geek-speak of my everyday life—what would be the point of leaving a good job with a great company (Intel) only to turn my joy into just another job? So when I decided to take the full-time photography plunge, it was with the very conscious personal commitment that I’d only photograph what I want to photograph, the way I want to photograph it. For me that means the natural light, color landscapes that I’d been photographing since the first shutter click of my Olympus OM-2, over thirty years ago: no people, no wildlife—basically, nothing that moves.

Ensuring my photographic pleasure also means doing things the way I’ve always done them: in addition to all natural light (I’m probably the only pro photographer alive who doesn’t own a flash), I choose to do no multi-image (HDR, manual blending, stitching) captures. I also rarely deviate from the 35mm 2/3 aspect ratio I was weaned on. But that’s just me. And just because I don’t do it, doesn’t mean I don’t marvel at other photographers’ monochrome, HDR, and artificial light wizardry.

I’ve also grown to become a huge fan of Photoshop, and the control it gives me: After all those years envying black and white shooters for their darkroom magic, it’s nice to see the playing field leveled a bit for us color shooters. In fact, many of my most successful images wouldn’t have been possible with the color transparencies I shot in my OM-2 days. But ultimately, despite Photoshop’s power, I still want my creativity to be in my camera, not my computer. On the other hand, I have no problem with photographers who use Photoshop creatively (as long as they do it honestly).

What I do have a problem with is the people who have so thoroughly embraced photography’s technical side that not only have they lost their joy, they seem bent on sapping the joy from anyone with a different idea or approach. These are the blog posters and forum contributors who will go to the mat for Canon vs. Nikon, Nik Dfine vs. Noise Ninja, or whatever their technical pulpit might be (I once witnessed a heated online debate about how to sign a print). So here’s a tip: If you find yourself arguing with somebody about some piece of photographic minutia, step away from the computer (these things rarely happen face-to-face), grab your camera, and go take some pictures. In other words, turn off your inner geek and connect with your creative side—the world (yours and mine) will be a better place for it, I promise.

I had no illusions of making money when I snapped the autumn leaf in this post. Nor was I wringing my hands about about shadow noise or corner sharpness. I was simply doing what I love, in this case scrambling on creekside rocks in the forest beneath Bridalveil Fall on a crisp autumn morning. Completely alone among rocks, leaves, and gentle cascades, I knew I was surrounded by far more images than I’d ever be able to find. The emotion I feel at these times is closer to the pure joy of a childhood Easter-egg hunt than anything else I experience in my adult life, and it’s no different from the feeling I used to experience when I was out with my Olympus. I never want to lose that.

Yosemite Photo Workshops

Autumn in Yosemite

Category: Bridalveil Creek, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: fall color, Photography, Yosemite

Roads less traveled

Posted on May 28, 2013

Sunrise Mirror, Mono Lake

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

1/60 second

F/10.0

ISO 200

32 mm

Sometimes our best opportunities arise when circumstances nudge us off our charted course.

One day earlier…

The morning before capturing this sunrise I’d been one of hundreds of photographers shoulder-to-shoulder on the beach at Mono Lake’s South Tufa. Competing with the thousands of photographers who flock to the Eastern Sierra to photograph the golden aspen each October, my brother and I were the first persons out there that morning, claiming our spots and waiting in the cold and dark for the sun. As expected, other photographers soon started accumulating—rather than finding their own scene, many simply assumed that my tripod meant I knew what I was doing and set up next to me. (Some didn’t even bother to pretend to study the surroundings first.)

By the time the sunrise started in ernest, I must have accrued thirty photographers, packed so tightly on both sides that if one had tipped over the rest would had collapsed in sequence like a row of dominos. The morning culminated with two of my newfound “companions” nearly coming to blows over a couple of square feet of lakeside real estate. Ahhh, the joys of communing with nature.

Channeling Lewis and Clark

The original plan was to return to South Tufa the following morning, our last at Mono Lake. But hoping to avoid that morning’s train wreck, Jay and I spent the afternoon exploring the tangled network of overgrown, rutted dirt roads encircling the lake, searching for other possibilities. For sunset we ended up somewhere on the north shore, traipsing about a half mile through (first) volcanic sand and (ultimately) shoe-sucking mud to an absolutely empty beach. In the days before ubiquitous GPS capability, we knew finding that very spot again, in the dark, would be nearly impossible, but it was pretty clear that the potential out there was off the charts regardless of where we landed.

So, despite a weather forecast that called for cloudless (boring) skies and temperatures in the 20s, on our final morning we rose dark and early and bounced behind my headlights through the sagebrush, in the general direction of yesterday’s discovery. When we found a spot wide enough to park we grabbed our gear and set out in the general direction of the lake, with no idea where we were or whether we’d made a mistake attempting this new location.

The eastern horizon was just starting to brighten as we slogged up to the lakeshore. Absolute calm had smoothed the lake to glass; from the Sierra crest behind us a formation of clouds had started to advance overhead. As the light came up the clouds continued their forward march, eventually spreading a herringbone pattern from horizon to horizon. Somehow we’d inadvertently stumbled upon the convergence of location and conditions photographers dream about.

The image you see here came fairly late in the shoot, after the sun crested the horizon. I used a 3-stop graduated neutral density filter to hold the brightness back to a manageable level, underexposing the sky even further to prevent the exquisite color from being washed out. This image has become one of my most popular, even gracing the cover of my book of images, “The Undiscovered Country.” But every time I look at it, I think first of that morning that never would have happened had we simply settled for the conventional choice.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

Reflections

Category: Eastern Sierra, Mono Lake, reflection Tagged: Mono Lake, Photography, reflections

Fire at will

Posted on May 20, 2013

Poppy Pastel, Sierra Foothills, California

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/125 second

F/4.0

ISO 400

100 mm with 12mm extension tube added

Maximize your investment

I clicked 54 versions of this scene (I just counted). I’m usually a pretty low volume shooter, sometimes not taking 54 pictures on an entire trip. And I have to admit, after years as a film shooter, the whole digital “fire at will” paradigm took some getting used to. But I’ve finally reached a place where I have no problem firing 54 frames in 30 minutes when the scene calls for it. The light came on for me when I realized that, while in my film days every single click cost money, with a digital camera, every click increases the return on my investment (the more images I have, the less per image my camera cost).

For example

These poppies were just a small handful of the thousands coloring a steep hillside near the Mokelumne River in California’s Gold Country. I’d been working the area for a couple of hours, using various combinations of macro, telephoto, and extension tubes to isolate and selectively focus poppies with various foreground/background relationships. I spent about an hour futzing around with compositions, occasionally stumbling upon something decent, but more often than not moving on to something else after a handful of mediocre frames. But the longer I worked, the more productive I became and the more I started seeing things the way my camera saw them.

The late afternoon sun that I’d been working with (and around) had just about left the scene when I decided to shift from one patch of poppies to similar patch about twenty feet away. I’d been concentrating on extremely close shots (inches from my subject) with at least 36mm of extension on my 100mm macro and 70-200 lenses, but when I saw this trio of poppies on (more or less) the same plane, I immediately pictured a slightly wider scene featuring this group sharp against a blurred background of poppies and grass.

Cutting back to a 12mm extension tube on my macro lens, I started with a wide aperture to limit the depth of field and spread the grass into a textured green canvas. With a slight breeze intermittently nudging the poppies, I switched to ISO 400 (in the few frames where I went smaller than f5.6, I bumped up to ISO 800). The preliminaries out of the way, I went to work refining my composition, framing the more or less centered foreground (sharp) poppies with the soft orange background poppy splashes.

Given the minuscule margin for error, I can’t imagine shooting something like this without a tripod. With my tripod I was able to use live-view to ensure precise focus, after each click evaluating everything from sharpness to exposure to composition, all with the security of knowing that the shot I’m reviewing is still sitting right there in my viewfinder, just waiting for whatever refinement I deem necessary.

Fifty-four frames later….

They don’t all have to be winners

Not only should you not be shy about shooting, your goal for each shot doesn’t necessarily need to be a “keeper” image. Often the purpose of a frame is to simply move you toward that keeper image. Sometimes that means a tangible improvement, but many times it’s just an education because nothing fosters creativity better than taking an “I wonder what happens if I do this” approach (followed by an effort to actually understand what happened). On the other hand, indiscriminate clicking (“The more I shoot, the better the chance I’ll find a keeper when I get home”) will wear out your camera faster than it improves your photography. In other words, shoot a lot, but make each shot serve a purpose.

Each frame that afternoon was a little different from the one before it: nearer, farther, up, down, left, right, more DOF, less DOF. While each wasn’t necessarily an improvement over the preceding frame, at the very least it advanced my understanding of the scene and gave me ideas for the next frame. And each gave me a variety of options from which to select when I could review and compare everything on a 27″ monitor. It was also lots of fun.

A Poppy Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: Photography, Poppies, wildflowers Tagged: extension tubes, macro, Photography, Poppies, Tripod, wildflowers

Photograph Yosemite’s weather

Posted on May 16, 2013

If you’re not prepared to miss a little sleep, get a little wet, or feel a little cold, you probably won’t make it as a Yosemite photographer. Last week Yosemite received daily doses of unusual (for May), but most welcome, rain. But those hardy few who endured the slippery rocks, soggy clothes, and wet gear, were rewarded with a variety visual treats that the comfortable masses never got to see.

When I’m shooting for myself (no scheduled workshop or personal guided tour), I only visit Yosemite when I expect something interesting in the sky. Sometimes that simply means a special moonrise, but usually it’s the promise of a storm that draws me.

Fresh snow

Yosemite is never more spectacular than it is with a coat of fresh snow draping rocks and branches. But if it’s fresh snow you’re after, you pretty have to be in Yosemite during the storm—even those who live in the Bay Area or Southern California are too late if they leave for Yosemite the second they hear Yosemite got snow. That’s because temperatures in Yosemite Valley during a snow storm are usually in the mid-30s—the melting starts as soon as the snow stops, and within hour or so of the sunlight hitting the snow, the trees have shed their white veneer. And while Yosemite Valley’s snow often remains on the ground for days, rapidly accumulating footprints and dirt quickly rob it of its pristine appeal.

During the storm

Storms in Yosemite often submerge the entire valley in a dense, gray soup, sometimes obscuring all but the closest trees and rocks. The narrow contrast range makes this kind of photography perfect for intimate, moody scenes, more than enough to keep me occupied while I wait for the storm to clear.

Clearing storm

A clearing storm is Yosemite’s main event. Photographers have been capturing them for as long as cameras have been in the park, long before Ansel Adams. Tunnel View’s elevated vantage point offers the best combination of easy access and photogenic scene, making it by far the most popular location to photograph Yosemite’s clearing storms. Because Yosemite’s weather clears from west to east, Tunnel View is where Yosemite Valley clears first; it’s where I usually wait out a storm. Tunnel View is also the best place to find a rainbow if you’re lucky enough to be there when the afternoon sun breaks through before the storm is done with the rest of the valley.

The problem with starting your Yosemite clearing storm shoot at Tunnel View is that it’s so spectacular, with conditions changing by the minute, that you may never leave. And that costs you a lot of opportunities to get some equally spectacular images at other, less photographed locations. When I’m by myself, leaving Tunnel View during a clearing storm is like ripping off a bandaid—it really hurts, but I’m always glad I did it. When I’m leading a group it’s an invitation to mutiny, but they usually come around when they see what they’d have missed had I not cracked the whip.

Be prepared

In the back of my car is a gym bag with all my wet weather clothing: wool gloves (wool will keep you warm even when it’s wet), a hat that covers my ears, at wide-brim waterproof hat for rain, a light rain parka (it goes over whatever jacket I’m wearing), waterproof over-pants, an umbrella, extra socks. It’s always there. With this gear and my waterproof boots, I can stay dry and cozy warm in the wettest weather.

The biggest problem photographing in weather isn’t keeping myself comfortable, it’s keeping my camera dry. While I do my best to keep my camera dry, I don’t really worry about a little rain on my camera or lens—the weather seal seems to be good enough for a light to moderate rain. And if I’m going to be standing in the rain for any period of time, I’ll put a plastic garbage bag over my camera and tripod. I usually keep a box of garbage bags in my car, but the trash liner or dry cleaning bag from the hotel room works just as well. The final piece of my wet weather ensemble is a towel, usually borrowed from my hotel room (just don’t forget to return it).

When it’s time to shoot, all of my effort goes to keeping water off the front of my lens. A lens hood helps in light, vertical rain, but I find them more trouble than they’re worth (I know this is blasphemy to some photographers, but the steps I take to eliminate lens flare are a topic for another day). Because I don’t own any kind of waterproof lens or camera cover, the umbrella I pack isn’t for me, it’s for keeping my lens dry when I’m shooting. The umbrella is usually sufficient, but when the rain is really coming down, and/or blowing in my face, I don’t even worry about water while I compose, meter, and focus. When I’m ready to shoot I dry the lens with my towel and click.

Getting to Yosemite during a storm

My favorite route into Yosemite is Highway 140, through the Arch Rock entrance. While that’s no more than personal preference most of the time, it’s downright essential when weather threatens. All the other three routes into Yosemite—41 from Fresno, 120 west from Manteca, and 120 east from Lee Vining (closed in winter)—climb over 6,500 feet and are frequently subject to ice, snow, chain requirements, and even closure. But the highest point on Highway 140 is Yosemite Valley. At only 4,000 feet, it’s much less likely to have weather problems.

Regardless of your route into the park, in winter you’re required to carry chains in Yosemite, even if you have four-wheel drive. You may be asked to show your chains when you enter the park, especially if weather threatens, and will be turned away without them. And if you’re in Yosemite Valley without chains and a chain requirement goes up, you can count on encountering a checkpoint—if that happens you’re pretty much stuck there until the requirement is lifted.

Today’s image

The image at the top of this post was captured last week, during a light rain at Tunnel View. My original sunrise plan was for a different location, but it was soon clear that we’d get no sunrise color that morning so I detoured my workshop group to Tunnel View. This was our first morning, and therefore our first opportunity to photograph a clearing storm—it turned out that we had many more opportunities during the workshop, but we were all pretty excited by what we saw as the light came up and the clouds lifted that morning.

I only clicked a handful of shots, mostly to demonstrate the composition variety Tunnel View offers. (Yosemite neophytes tend to spend too many clicks on the wide frames, and I want to show them that there are lots of tighter compositions possible too.) I don’t shoot black and white, but several people in the group had great success converting images from that shoot to black and white.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, Half Dome, Yosemite Tagged: Photography, rain, Yosemite

(More) Yosemite spring reflections

Posted on May 13, 2013

I just wrapped up two Yosemite spring workshops, four and five day visits separated by less than two weeks. What struck me most about these two workshops was, despite pretty similar conditions (maximum waterfalls, green meadows, blooming dogwood, and lots of people), how the tremendous difference in weather dictated a completely different approach to photographing Yosemite Valley.

In the first workshop our weather was fairly static, with a nice daily mix of clouds and sun that allowed me to plan shoots early in the day and pretty much stick with the plan throughout the day. We had a couple of night shoots, including one night photographing a moonbow (lunar rainbow) at the base of Lower Yosemite Fall. A particular highlight for this group was the variety of daylight rainbows on Bridalveil and Yosemite Falls. These rainbows appear with clockwork reliability at various viewpoints when the sun is out. Getting the group in position to photograph them is a particular source of personal pleasure (that makes me appear far smarter than I actually am).

In the second workshop we received rain each day, rarely a downpour, but frequently heavy enough to cause me to alter our plans, sometimes completely ad-libbing locations at the last second based on what I saw the conditions. With rain comes clouds, to our detriment when they dropped low enough to obscure the view, and to our great advantage when they parted enough to accent Yosemite Valley and frame the soaring monoliths and plunging waterfalls everyone had traveled to photograph. And because Yosemite’s clearing storms such are a rare treat, this group made frequent (and productive!) visits to Tunnel View as wave after wave of rain and clearing passed.

Another, more subtle, difference between the two workshops was the state of the dogwood bloom. The April group caught the dogwood just as it started to pop out, while the May group found the dogwood far more mature. Ample sunlight allowed the April group to concentrate on backlit flowers and leaves, and the freshness of the blooms provided lots of intimate compositions featuring one or two flowers.

In May the blooming dogwood was more widespread, but many of the flowers were a bit tattered. With heavy overcast and a persistent breeze, close portraits were difficult (but not impossible), so I encouraged the group to concentrate more on larger, more distant dogwood scenes.

On the drive home from the May workshop I reflected a bit on the two workshops and was glad I didn’t have to choose a favorite. With summer almost upon us, as Yosemite’s skies clear, its waterfalls dry, and the tourists swarm, I have plenty of images and memories to hold me over until fall, when my next “favorite” season will deliver an entirely different set of new opportunities.

* * * *

I do it all over again next spring, April 11-14 and May 11-14.

Category: Dogwood, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: dogwood, Photography, Yosemite

A study in contrast

Posted on May 9, 2013

I’d billed my just completed Yosemite spring workshop as a crescent moon workshop. The plan was (among other things) to photograph a crescent moon rising above Yosemite Valley in the pre-sunrise twilight on consecutive mornings. This spring waning crescent is one of my very favorite Yosemite phenomena, something I try not to miss each May (when it aligns best with Half Dome from the most accessible locations). But Mother Nature had other ideas. Instead of the reliably clear skies California typically enjoys in May, this year a stubborn low pressure system parked off the coast and pumped moisture into Northern California. But despite a pessimistic forecast that called for rain and lots of clouds, my hardy group rallied at 4:45 each morning to be in place in the unlikely event the moon showed.

For our first morning I’d plotted a location beside the Merced River to photograph a 12% crescent moon that would appear from behind Half Dome just before 5:15. But we pulled up to the spot to find that the clouds had swallowed Half Dome; we didn’t even get out of the cars. Instead we hightailed it to Tunnel View for the first of what would become many Yosemite Valley clearing storm experiences (that most Yosemite visitors can only dream about). By the time we arrived the sky had brightened significantly, the clouds above Half Dome had started to part, and wisps of mist swirled on the valley floor beneath Bridalveil Fall.

My plan for our second morning was to start at Tunnel View at around 5:00, exactly one hour before sunrise. I knew a 6% crescent moon would crest Sentinel Dome (between Half Dome and Cathedral Rocks) at 5:13 (+/- a minute or so), and wanted to give everyone enough time to set up in the dark. It was still quite dark when we arrived, with just enough light to know something special was happening in Yosemite Valley. I hustled everyone to the wall and assured them that their cameras would be able to accumulate enough light to reveal far more detail than our eyes could see.

To give you an idea of how dark it was when we started shooting, the image at the top of page is a 30 second exposure at f4 and ISO 800. If the sky had been clear when I clicked this frame, the moon would have been balanced atop Sentinel Dome, almost exactly as it was in May, 2008 (below). Contrast the above clearing storm exposure settings with the settings for my crescent moon image below: 5 seconds at f7 and ISO 200. Both were almost exactly 45 minutes before sunrise, but in the crescent moon image I intentionally underexposed the scene to hold the color in the sky (washed out to my eyes by the rising sun), hide foreground detail, and etch the distinctive outline of Half Dome and Sentinel Dome in silhouette. The clearing storm image, on the other hand, is actually slightly overexposed to reveal beauty hidden by the darkness in Yosemite Valley.

So if there’s a single takeaway from these two images, it’s that just as with our composition decisions, our exposure settings are creative choices allowing us to express the world in ways that are different, but no less true, than the human experience. Photography is most powerful when it can expand our perception of reality to reveal unseen or overlooked aspects of nature, whether it be the simple shapes of Yosemite Valley, or the hidden world before the sun.

A few words about night sky color

Before the inevitable “that color isn’t natural” comments, let me strike preemptively by addressing the common misconception that color is an inherent, exclusive quality of an object or scene. While color is indeed a defining characteristic, of equal importance is the light illuminating an object or scene. Just as the sky is blue at noon and orange at sunset, every scene in nature changes color throughout the day.

Color becomes a bit more problematic at night, when there isn’t light enough light for the cones in our eyes to register color. But that doesn’t mean the color isn’t there. Camera’s have many disadvantages compared to human vision, but one area where a camera excels is its ability to accumulate light. Using this capability, photographers can reveal a scene’s natural color by brightening the scene far beyond the human experience.

The night side of Earth is simply shadow, much like standing behind a tree (an extremely large tree). And as with the world behind a tree, all direct sunlight is blocked, leaving the shaded area illuminated solely by reflected light. Because sunlight’s shorter, violet and blue wavelengths are more easily reflected (sunlight’s longer wavelengths pass straight through to illuminate and warm Earth’s sunlit side exclusively), they’re the only wavelengths left to illuminate Earth’s night side. So, while the night sky looks black to our eyes, it is in fact quite blue. (And we have the images to prove it.)

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Yosemite Tagged: clearing storm, Photography, twilight, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About