Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Four sunsets, part three: A marvelous night for a moondance

Posted on February 19, 2014

Moondance, Half Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/5 second

125 mm

ISO 100

F11

How many Yosemite moonrise images are too many? I have no idea, but I’ll let you know as soon as I find out.

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

- Read the second in the series here: Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

5:10 p.m.

I stand on the bank of the Merced River, eyes locked on the angled intersection of Half Dome’s sharp northeast edge and its adjacent, tree-lined ridge. If the clouds cooperate, and I’ve done my homework right, a nearly full moon (96%) will be poking above this intersection any minute. We’d been fortunate the first two sunsets of my workshop; dare I hope for one more?

If the moonrise happens as I plan (hoped), the sight could rival what we’d gotten from Horsetail Fall on the first two nights of our workshop. But right now the sky behind Half Dome is smeared with thin-ish clouds—how thin I won’t know until the moon appears (or doesn’t). Gazing heavenward, I find it odd that a moonrise, something that can be predicted with such absolute precision, is so subject to weather’s fickle whim. And the clouds aren’t my only concern—just a half-degree error in my plotting would put the moon behind Half Dome and out of sight.

Few things in nature thrill me more than a moonrise. Camera or not, crescent or full, I love everything about a it: the obsessive plotting and re-plotting that gets me out there in the first place; the hand-wringing anticipation while I await the moon’s appearance; the first white pinprick of moonlight on the horizon (Is that it? There it is!); the ridge-top evergreens silhouetted against the rising disk; the glowing sphere hovering above the darkening landscape; and finally, the moonlit landscape beneath a star-studded sky. Everything.

So it shouldn’t surprise that virtually all of my photo trips—workshops and personal—are scheduled around the moon’s phase and some condition of the night sky. Sometimes I target a full moon, sometimes a crescent, and sometimes I want no moon at all (for dark skies that reveal the most stars)—the choice depends on the kind of moonrise and/or night photography I think best suits the landscape I’m traveling to photograph. But because this workshop is timed to coincide with the few February days that Horsetail Fall might turn a molten red at sunset, a calendar window I shrink even further to avoid the crowds that flock a little later in February, the moon is rarely a priority when I schedule the Horsetail Fall workshop. But I still check. And when I started planning my 2013 Yosemite Horsetail Fall workshop a couple of years ago, I was thrilled to discover that not only could I could time this trip for a full moon, I’d also be able to align that moon with Half Dome at sunset. Twice.

5:13 p.m.

I check my watch: 5:13. Sunset is 5:35; the moon should appear almost adjacent to Half Dome at about 5:15, then slowly rise, like a ball rolling uphill along Half Dome’s left side. By 5:30 the disk will have almost reached Half Dome’s summit, less than its own width with from the granite face. That is, if I’ve done my homework right. 5:14.

Any minute now….

I’d done all my figuring months in advance, which of course didn’t stop me from double-, triple-, quadruple-, and so-on-checking my results in the days leading up to my waiting beside the Merced River with a dozen or so other photographers. Part of my anxiety is the particularly fortuitous alignment of location, moon, and time that put the moon appearance above Half Dome right in my “ideal” sunset window as viewed from one of my favorite Yosemite locations. Not only does this spot provide a clear, relatively close view of Half Dome, it also is at a nice, reflective bend in the Merced River. Even without the moon this is a nice spot, end everyone in the group seems to be finding things to photograph. But I want the moon tonight. Really, really want the moon.

(You really don’t need to read this section)

My moonrise/set workflow was in place long before smartphones apps and computer software laid it all out for any photographer willing to look it up. But those tools are new tricks and I’m an old dog. So here’s how I’ve done it for years:

- Use my topo map software to determine the latitude and longitude of the location I want to photograph.

- Give my location’s latitude and longitude to my Focalware app (or, if I need the data to be a little more granular, the US Naval Observatory website), which returns the moon and sun rise/set altitude (degrees above a flat horizon) and azimuth (the angular distance relative to due north, from 0 to 360 degrees—imagine a clock: 12 is 0 degrees; 3 is 90 degrees; 6 is 180 degrees and so on).

- Next I plug the moon’s altitude/azimuth for my location into the plotting tool of my computer’s mapping software. This draws a line from my location (where I’ll be with my camera) to the location of the moonrise (or set). Most importantly, the line shows the moon’s alignment with whatever landscape feature I’m interested in (such as Half Dome). It also gives me both the distance and the elevation change between my location and the point above which it will rise.

- Finally, I use the elevation and distance data with the trig functions of a scientific calculator to get the altitude to which the moon must rise before it’s visible from my vantage point.

If this all sounds convoluted, that’s probably because it is. I suggest that you try something like The Photographer’s Ephemeris or Photo Pills, which does all this for you. But like I say, that’s a new trick….

5:15 p.m.

I squint, hoping to engage my x-ray vision enough to make out the moon’s outline through the clouds. Nothing. With conditions fairly static, the group has gotten their shots and is chatting more than clicking. Moon or not, the photography will improve as the light warms toward sunset. I walk uphill, away from the river and slightly upstream to improve my angle of view. Still nothing. (Did Ansel Adams experience this angst?)

We’ve reached the time that I expect the moon to appear. I’ve been plotting the moon long enough to be fairly confident within about one moon’s width (a half degree in either direction) of where it will rise, and within plus/minus two minutes of when it will rise. But the whether of seeing a moonrise depends on, well, the weather. Will rain, snow, or even just a rouge cloud shut us out? There’s really no way to know until the day arrives. And sometimes, for example this very instant, I can’t tell whether the sky will cooperate until I actually see the moon.

I’ve learned that the best time to photograph a full moon (when I say “full,” I often mean almost full, generally between 95 and 100 percent of the complete disk illuminated) is during a ten minute window straddling sunset. Much earlier and the light isn’t particularly interesting, and there isn’t enough contrast between the moon and the sky for the moon to stand out dramatically; much later and there’s too much contrast between the moon and everything else in the scene for the camera to handle.

Choosing this location introduces another unknown. Remember when I said that I can pinpoint the moonrise within about its width? Well, in this case that margin of error is just enough to give me pause, because rising slightly to the right of where I think it will rise puts the moon behind Half Dome until about five minutes after sunset. Sentinel Bridge, just a short distance downstream, would have been safer, but the Sentinel Bridge Half Dome shot is far more common, the bridge is usually teaming with people at sunset, and the moon would have been a little higher in the sky during “prime time.” So here we stand.

5:17 p.m.

What’s that faint white blob in the clouds? Without saying anything I squint and look closer. Sure enough, there it is, barely visible, less than one degree above the ridge (its rise above the ridge a couple of minutes ago must have been obscured by the clouds), pretty much where I expect it. Phew. I announce the moon’s arrival to the rest the group, but need to guide their eyes to it. As everyone’s attention returns to their cameras, I cross my fingers for the clear sky in its path to hang in there until at least sunset.

5:25-5:45 p.m.

The moon finally climbs above the clouds and I exhale. Still daylight bright, it now makes a striking contrast against the darkening sky. For the next fifteen minutes we shoot continuously, pausing only to recompose and monitor the highlights. Compositions, which I’d had everyone practice before the moon arrived, range from wide reflections that reduce the moon to a tiny accent, to tight isolations of the moon and Half Dome’s face.

As sunset approaches, the biggest concern becomes those lunar highlights—too small to register on the camera’s histogram, the moon’s face is easily blown out as we try to give the darkening foreground more light. Before we started I made certain everyone has engaged their camera’s Highlight Alert (“blinking highlights”) feature. They all know that when the moon starts flashing, they’ve reached the exposure threshold and must back off on their exposure and lock it in (a few “blinkies” are recoverable in Lightroom or Photoshop, but if the entire disk is flashing, the moon’s detail is probably lost for good)—while the moon will remain the same brightness (can’t take any more exposure), from that point on the foreground will continue darkening until it becomes too dark to photograph. Then we go to dinner.

Like everyone else, I used a variety of compositions. I already have a wide reflection image from a prior shoot, so the image I share here is a moderate telephoto—any tighter (to enlarge the moon further) would have truncated some of Half Dome’s face, something I just cant bring myself to do.

We finally wrapped up at about 5:45, when long exposures to bring out detail in the dark landscape made capturing detail in the bright moon impossible. Everyone was pretty thrilled at dinner, and even though the clouds thickened and washed out our planned moonlight shoot, there were no complaints. And little did we know, Mother Nature had concocted a grand finale for our final sunset.

Join me in Yosemite

PURCHASE PRINTS || PHOTO WORKSHOPS

A Gallery of Yosemite Moons

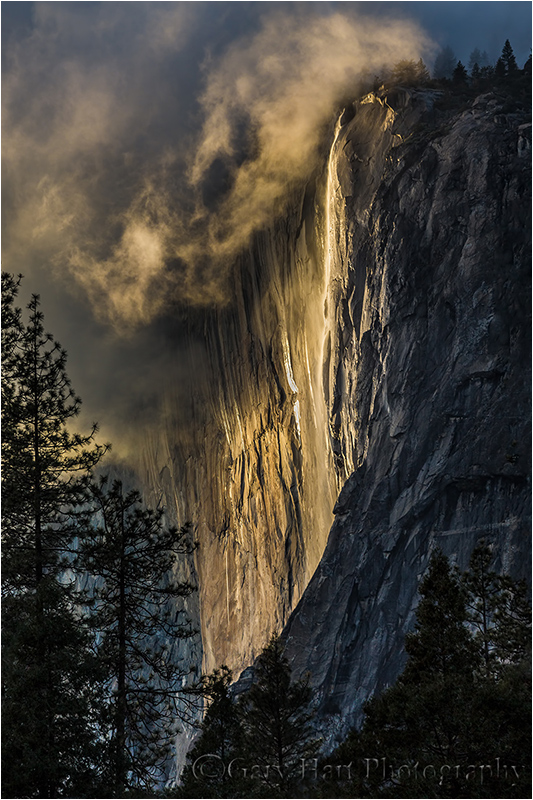

Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

Posted on February 16, 2014

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

While we’d been incredibly fortunate with our Monday night Horsetail Fall shoot, we didn’t get the molten glow everyone covets (though I’d argue, and several agreed, we got something better). Nevertheless, based on the relatively clear skies, I decided to take everyone back for one more try on Tuesday.

On Monday we’d been able to photograph in relative peace from my favorite spot on Southside Drive, but given that the weekend storm had left us in its rearview mirror, and that word had no doubt gotten out that Horsetail Fall was once again flowing, I guessed that the Horsetail day-trippers (Bay Area, Los Angeles, Central Valley photographers who cherry-pick there Yosemite trips based on conditions) would begin crowding into Yosemite Valley. To be safe, I got my group out there a little after 4:00 (sunset was 5:35). Despite being earlier, both parking turnouts were already teeming cars (if everyone squeezes, there might be room for fourteen legally parked cars)—just a few minutes later and we’d not have found room for our three vehicles (all the late arriving cars that had attempted creative, shoulder parking solutions returned to find parking tickets decorating their windshields). With so many more cars, I wasn’t surprised to find my preferred spot down by the river was already starting to fill—but we spread out a bit and everyone managed to squeeze in.

Unlike Monday evening, the Tuesday sky started mostly clear, with only an occasional wisp of cloud floating by. While the scene lacked the drama of Monday, the clear skies boded well for the fiery show we were all there for. We watched the crisp, vertical line separating light and shadow advance unimpeded across El Capitan. The mood was optimistic—borderline festive. Then, a little after five, with no warning the light faded and El Capitan was instantly reduced to a homogeneous, dull gray. Many people reacted as if their team had fumbled on the two yard-line, but those of us who know Horsetail Fall’s fickle disposition just smiled.

In all the years I’ve been photographing Horsetail Fall, I’ve come to recognize how much it likes to tease—while this is more of a gut feeling, it has always seemed to me that the evenings when the shadow marches without pause toward sunset, the light is much more likely to extinguish right before the prime moment. On the other hand, my best success seems to come on the evenings when the light comes and goes, teasing viewers right up until it suddenly reappears in all its crimson glory just before sunset. So, until the light disappeared I was a little concerned that things were going too well. But when the light faded I was able to guide them away from the ledge and reassure them that there’s no reason to panic just yet. And sure enough, about ten minutes later the sunlight came flooding back and everyone exhaled.

As shadow advances from the west, the remaining light warms—by 5:25 it had reached a rich amber. Once it reaches that stage my advice to everyone was that, since the show will either get better (more red) or worse (the light snuffed), and there’s no way of telling which it will be, they should just keep shooting until the light’s gone. And that’s what we did. At first there were no clouds and my composition was fairly tight to eliminate the boring sky. Then, just a few minutes before the “official” 5:35 sunset (I should add that “sunset” when you see it published refers to the time the sun sets below a flat horizon—it set far earlier for those of us on the valley floor, and it wouldn’t set on elevated Horsetail Fall until nearly 5:45), a nice cloud wafted up from behind El Capitan and I quickly went wider to include it.

On the way to dinner with the group I breathed a sigh of relief knowing that my life had just become much easier. For many in the group, what we’d just photographed was their primary workshop objective—for some Horsetail Fall is a bucket-list item. But the nights Horsetail Fall doesn’t light up are far more frequent than the nights it does, and in fact I’ve seen Februarys when it’s only lit up like that once or twice (and I’m sure there have been years when it doesn’t happen at all). While I knew nobody would hold me accountable if Horsetail didn’t put on a show for us, the fact that it did (not to mention the fabulous Horsetail shoot of our first night), meant that I was free to focus the group’s final two sunsets two very special moonrises.

Next up, sunset number three: A marvelous night for a moondance

* * *

Read when, where, and how to photograph Horsetail Fall

Join me next February when we do it all over again

Category: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, Photography, Yosemite

Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

Posted on February 14, 2014

If the National Weather Service website were human, it would have long ago slapped me with a restraining order. You see, California is in the throes of an unprecedented drought that has shriveled lakes, rivers, creeks, and reduced even the most robust waterfalls to a trickle. With my Yosemite Horsetail Fall (which on a good day is rarely more than a thin white stripe on El Capitan’s granite) workshop just around the corner, recent weeks have seen me behave more like an obsessed infatuee, as if constant monitoring will somehow make my weather dreams come true. But so far this winter, each time I thought Mother Nature had winked in my direction, I found my hopes quickly dashed as every promising storm made an abrupt left into the open arms of the already saturated Pacific Northwest.

So, imagine my excitement when, just in time for this week’s workshop, an atmospheric river (dubbed the “Pineapple Express” for its origins in the warm subtropical waters surrounding Hawaii) took aim at Northern California. During the four days immediately prior to my workshop, our mountains were drenched with up to ten inches of liquid—not nearly enough to quench our three-year-and-counting drought, but more than enough to recharge Yosemite’s parched waterfalls for the three-and-a-half days of the workshop. Phew.

Monday morning I arrived in Yosemite to find, as hoped, the waterfalls brimming and Horsetail Fall looking particularly healthy. Eying Horsetail from the El Capitan picnic area a few hours before the workshop started, I suddenly remembered the stress that comes with other photographers counting on me for the bucket-list shot they’d traveled so far to capture. It occurred to me that hen Horsetail Fall is dry I can concentrate without distraction on Yosemite’s other great sunset options; when Horsetail is flowing, I need to decide whether to go for the notoriously fickle sunset light and risk no photographable sunset at all if it doesn’t happen. That’s because, not only does Horsetail Fall need water, the red glow everyone covets also requires direct sunlight at the exact instant of sunset—never a sure thing, even on seemingly clear days. And if Horsetail doesn’t get sunset light, there’s little else to photograph from its prime vantage points. With the forecast for the workshop’s duration called for a disconcerting mix of clouds and blue sky, our odds were even longer than ordinary. Compounding my anxiety was the full moon that I’d promised for workshop sunsets three and four (of four total sunsets)—if we don’t get Horsetail on sunset one or two, I’d have to decide between going for Horsetail or the moon. (And woe betide the workshop leader whose group watches a fiery sky or ascending moon from an unsuitable location—tar and feathers, anyone?)

During the orientation I did my best to establish reasonable expectations. I told the group that we’ll go all-in on Horsetail for sunsets one and two, and that if it doesn’t happen, I’ll decide our priority for sunsets three and four based on the conditions. What I meant was, we’ll go all-in for Horsetail on sunsets one and two, and I’ll hope like crazy it that does happen and I won’t have to decide anything for sunsets three and four. What followed was four sunsets filled with anxiety, each culminating with a rousing success—two our our successes were of the exactly-what-I’d-hoped-for variety, while the other two were far beyond what I could have imagined.

Sunset number one, above, was in the more than I could have imagined category. After the orientation I took the group to Tunnel View, where we kicked off the workshop with Yosemite Valley beneath a nice mix of clouds and sky. From there we headed to the night’s sunset destination, my favorite Horsetail Fall view on Southside Drive. A few years ago I could pull in to this spot a few minutes before sunset and be relatively confident of finding enough room for my entire group. But this spot is no longer a secret; on the drive there I crossed my fingers that the storm had kept most of the day-trip photographers home—if not, Plan B was to loop over to the El Capitan picnic area where there’s more parking and ample room for many photographers. On this afternoon my concerns were unwarranted as we found only two other cars there, and nobody down by the river where I like to set up. And set up we did, with a little more than an hour to wait. From the time we arrived the clouds were nice, but with no sign of the sun the scene was a little flat, with gray the predominant color—nevertheless, I encouraged everyone to be ready because it can change in a heartbeat. Little did I know….

As we waited we watched Horsetail Fall, spilling more water than I’d seen in years, play peek-a-boo with the storm’s swirling vestiges. But without direct sunlight, the scene, while pretty, wasn’t spectacular. Then, shortly before 5:00, without warning the clouds lit up like they’d been plugged in and I (unnecessarily) told everyone to start shooting, that we have no idea how long this light will last. For the next ten minutes we were treated to a Horsetail Fall show the likes of which I’ve never seen. Suddenly the exposures, quite easy in the flat gray, became quite tricky and I spent lots of time bouncing between workshop participants struggling with exposure. I managed to get off a handful of frames, some fairly wide, and a few a little tighter like this one. When the light faded we were left with cards devoid the “classic” Horsetail image; instead, we had something both beautiful and unique, a difficult combination for such a heavily photographed phenomenon. From the conversations in the car, and from images shared later during image review, it was pretty clear that everyone else was as happy as I was. Nevertheless, I sensed most still wanted the red Horsetail image, and I was ready to give it one more try with sunset number two.

Next up, sunset number two: The “classic” Horsetail.

* * *

Read when, where, and how to photograph Horsetail Fall

Join me next February when we do it all over again

Category: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, Yosemite Tagged: Horsetail Fall, Photography, Yosemite

Securing the border

Posted on January 8, 2014

If you’ve ever been in one of my workshops, or (endured) one of my image reviews, you know where I’m going with this (I can sense eyes rolling from here). But I hope the rest of you stick with me, because as much as we try be vigilant, sometimes the emotion of a scene overwhelms our compositional good sense—we see something that moves us, point our camera at it, and click without a lot of thought. While this approach may indeed capture the scene well enough to revive memories or even impress friends, you probably haven’t gotten the most out of it. So before every click, I do a little “border patrol,” a simple mnemonic that reminds me to deal with small distractions on the perimeter that can have a disproportionately large impact on the entire image. (I’d love to say that I coined the term in this context, but I think I got it from Brenda Tharp—not sure where Brenda picked it up.)

To understand the importance of securing your borders, it’s important to understand that our goal as photographers is to create an image that invites viewers to enter, and persuades them to stay. And the surest way to keep viewers in your image is to help them forget the world beyond the frame. Lots of factors go into crafting an inviting, persuasive image—things like balance, visual motion, and relationships are essential (topics for another day), but nothing reminds a viewer of the world beyond the frame faster than objects jutting in or cut off at the edge, or visually “heavy” (large or bright) objects that pull the eye away from the primary scene. To avoid these distractions, for years I’ve been practicing, and advocating, border patrol before clicking. Just run your eyes around the perimeter, note everything that’s on or near the border, and ask yourself if that really is the best place for the edge of the frame.

Sometimes border patrol is easy—a simple scene with just a small handful of objects to organize, all conveniently grouped toward the center, usually requires very little border management. But more often than not we’re dealing with complex scenes containing multiple objects scattered throughout and beyond the frame: leaves, rocks, clouds, whatever, with no obvious demarcation.

Incoming Storm, Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley

Border patrol for this image was relatively simple—with nothing prominent near the edges, I was primarily concerned about visual balance, though I did conduct a bit of border patrol on the sky to ensure that I chose the best place to break the churning (rapidly moving) clouds.

The frigid Yosemite scene at the top of his post was as difficult as it was beautiful. With my camera in live-view mode atop my tripod, I relatively quickly came up with a composition that encompassed the beauty and felt fairly balanced, but all the snow-capped rocks, patches of ice, and randomly distributed hoarfrost made it pretty much impossible to find the perfect place for my border.

The circle of five snow-covered rocks in the left foreground was my foreground anchor—I needed to give these rocks space, and to balance them with the field of hoarfrost blooms in the right foreground. I was very aware of the rocks cut off in the left and right middle-ground, but going any wider introduced all kinds of new problems (just outside the current frame) at the bottom and on both sides. On the other hand, a tighter composition would have cut off the ice-etched trees that stood out so beautifully against the shaded evergreen background. Sigh. So, I did what every photographer must do in virtually every image: compromise. Compromise in this case meant opting for the lesser of multiple evils, hopeful that the unique drama of this frigid scene would be enough to overcome its flaws.

What flaws? I thought (hoped) you’d never ask. After several minutes of shifting up/down, left/right, forward/backward (while crossing my fingers that the ice on which I was stationed would hold out), and zooming in and out, I managed to get all of my icy trees at the top of the frame and find a relatively clean patch of water in front of me for the bottom of the frame. The large rock cut off on the middle right doesn’t bother me too much either—large objects cut in the middle can serve as frames that hold the eye in the scene. But if I could have had complete creative control over this scene (this is where painters have a distinct advantage), I’d have done something about those small rocks cut off on the middle left—I know nobody would be consciously aware of them, but there’s nothing like a clean border to hold a viewer in the scene, and those rocks just aren’t clean to my eye.

Because you can actually practice border patrol, and composition in general, in the comfort of your home, another frequent theme in my image reviews is the value of the crop tool as a learning device. Pick any image—yours or someone else’s—and see how many compositions you can find in it. The goal isn’t to create usable images (you’ll loose too many pixels for that), it’s to train your eye to see things you currently miss in the field. I promise that if you do this enough, you’ll find yourself naturally seeing compositions and fixing obvious problems before you click.

Category: How-to, Merced River, snow, Yosemite Tagged: Photography, winter, Yosemite

Two out of three ain’t bad

Posted on December 20, 2013

Moonlight Cathedral, El Capitan, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

30 seconds

23 mm

ISO 1600

F8

I scheduled my Yosemite Comet ISON photo workshop way back when astronomers were crossing their fingers and whispering “Comet of the Century.” Sadly, the media took those whispers and amplified them a thousand times—when ISON did its Icarus act on Thanksgiving day, its story became the next in a long line of comet failures (raise your hand if you remember Kohoutek).

But anyone who understands the fickle nature of comets would be foolish to get too excited about (or plan an event solely around) a comet’s promised appearance. So I scheduled this workshop knowing that even if the comet fizzled, storms and snowfall can make winter in Yosemite Valley spectacular. But, because snowfall in Yosemite is also far from a sure thing, to further enhance our chances for something special, in addition to Comet ISON and winter conditions, I scheduled this workshop to coincide with the December full moon. And while we didn’t get the comet, well, to quote Meat Loaf, “two out of three ain’t bad.”

Yosemite Valley received nearly a foot of snow a few days before the workshop started. Given Yosemite frequent sunshine and relatively warm temps, normally that snow would have all but disappeared from the trees and rocks within a few hours, and within a couple of days would have been marred by large brown patches—exactly what happened in the unshaded parts of Yosemite Valley. But because this storm was followed immediately by a cold snap, those parts of the valley that remained all day in the shade of Yosemite’s towering, sheer granite walls (mostly the south and/or west side of the valley) didn’t shed their snow and actually accumulated ice as the week went on.

Valley View was the prime beneficiary of this all day shade—by the time my workshop started, snow-capped rocks, hoarfrost blooms, and a sheet of windowed ice had elevated this always beautiful location to more beautiful than I’ve ever seen it. Full moon notwithstanding, it was the highlight of the workshop. Taking advantage of our unique opportunity, my group photographed Valley View early morning, late afternoon, at sunset, and (as you can see) by moonlight.

There are lots of things human vision can do that the camera can’t—fortunately, one of those things is not see in low light. While moonlight adds beauty to any scene, when a scene starts out off-the-charts-beautiful, moonlight makes it a downright spiritual experience. Though moonlight is beautiful to the eye, even at its brightest, a full moon isn’t bright enough to reveal all the beauty present. Enter the camera.

Giving this scene lots of light allowed me to reveal how it would appear if your eyes could take in as much light as, say, an owl. Or your cat. The blueness of the sky, the sparkling ice crystals, the reflection in the river—that beauty is no less real just because it’s invisible to our eyes.

To reveal all this “invisible” beauty, I started at ISO 800, f4, 15 seconds. But the unusually extreme (for moonlight photography) depth of field this composition required caused me to increase to ISO 1600 and 30 seconds to allow the extra DOF f8 provides. And I was thrilled to discover that there was enough light to enable live-view manual focus (my now preferred focus method for all situations). According to my DOF app, focusing about eight feet into the frame would give me sharpness from front-to-back, but just to be sure, after capture I magnified image in my LCD and checked the ice in the foreground and trees atop El Capitan.

The other problem I needed to deal with was lens flare, an easy thing to forget about when photographing in the dark. But the moon is a bright light source and all the lens flare rules that apply to sunlight photography also apply to moonlight—if moonlight strikes your front lens element, you’ll get lens flare. Since I hate lens hoods, I manually shield my lenses in flare situations. A hat works nicely, but there was no way I was taking my snuggly warm hat off, so I shaded my lens with my hand for the entire 30 seconds of my exposure.

BTW, see that bright light shining through the tree at the base of El Capitan? That’s Jupiter.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Gallery of Snow and Ice

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, Moonlight, snow, stars, Valley View, Yosemite Tagged: moonlight, Photography, snow, Yosemite

Oops

Posted on December 17, 2013

Winter Moonrise, Merced River, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/10 second

40mm

ISO 800

F16

Last Friday evening, this professional photographer I know spent several hours photographing an assortment of beautiful Yosemite winter scenes at ISO 800. Apparently, he had increased his ISO earlier in the day while photographing a macro scene with three extension tubes—needing a faster shutter speed to freeze his subject in a light breeze, he’d bumped his ISO to 800. Wise decision. But, rushing to escape to the warmth of his car, rather than reset the camera to his default ISO 100 the instant he finished shooting, he packed up his camera with a personal promise to adjust it later, when his fingers were warmer—surely, he rationalized, removing the extension tubes and macro lens would remind him to reset the ISO too. (You’d think.) But, despite shutter speeds nowhere near what they should have been given the light and f-stop, he just kept shooting beautiful scene after beautiful scene, as happy as if he had a brain.

I happen to know for a fact that this very same photographer has done other stupid things. Let’s see…. There was that time, while chasing a sunset at Mono Lake, that he drove his truck into a creek and had to be towed out. And the two (two!) times he left his $8,000 camera beside the road as he motored off to the next spot. And you should see his collection of out-of-focus finger and thumb close-ups (a side effect of hand-holding his graduated neutral density filters). Of course this photographer’s identity isn’t important—what is important is dispelling the myth that professional photographers aren’t immune to amateur mistakes.

And on a completely unrelated note…

Let’s take a look at this image from, coincidentally, last Friday evening. Also completely coincidentally, it too was photographed at ISO 800 (go figure)—not because I made a mistake (after all, I am a trained professional), but, uhhh, but because I think there are just too many low noise Yosemite images. So anyway….

This was night-two of what was originally my Yosemite ISON workshop—but, after the unfortunate demise of Comet ISON and a week of frigid temperatures in Yosemite, became my Yosemite ice-on workshop. That’s because, to the delight of the workshop students (and the immense relief of their leader), much of the one foot of snow that had fallen the Saturday before the workshop’s Thursday start had been frozen into a state of suspended animation by a week of temperatures in the teens and low-twenties.

Each day we rose to find nearly every shaded surface in Yosemite sheathed in a white veneer of snow and ice. (Valley locations that received any sunlight were largely brown and bare.) And the Merced River, particularly low and slow following two years of drought, was covered in ice in an assortment of textures and shapes from frosted glass to blooming flowers. Adding to all this terrestrial beauty was a waxing moon, nearly full, ascending our otherwise boring blue skies and illuminating our nightscapes.

On Friday night I guided my group to this spot just downstream from Leidig Meadow. There we found the moon, still several days from full, glowing high above the valley floor, and Half Dome reflected by a watery window in the ice. I captured many versions of this scene, from tight isolations of the reflections to wide renderings of the entire display. It’s too soon to say which I like best, but I’m starting with this one because it most clearly conveys what we saw that evening.

I chose a vertical composition because including the moon in a horizontal frame would have shrunk Half Dome and the moon, and introduced elements on the right and left that weren’t as strong as Half Dome, its reflection, and the snowy Merced River. (Sentinel Rock is just out of the frame on the right—as striking as it is, I wanted to make this image all about Half Dome.)

My f16 choice was to ensure sharpness throughout the frame, from the ice flowers blooming in the foreground, to Half Dome and its reflection. As you may or may not know, the focus point for a reflection is the focus point of the reflective subject, not the reflective surface. That means when photographing a reflection surrounded by leaves, ice, rocks, or whatever, you need to ensure adequate DOF or risk having either the reflection or its surrounding elements out of focus. Here I probably could have gotten away with f11, but my iPhone and its DOF app were buried beneath several layers of clothes, and using it would have require removing two pair of gloves.

I’d love to say that I chose ISO 800 to freeze the rapids, but I’m not sure you’d buy it. So I’m sticking with my too many low noise Yosemite images story and moving on. (A few cameras ago, ISO 800 would have meant death to this image, but today, thankfully, it’s mostly just a lesson in humility.)

A Yosemite Winter Gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: full moon, Half Dome, Humor, Merced River, Moon, reflection, snow, Yosemite Tagged: Half Dome, moon, moonrise, Photography, snow, Yosemite

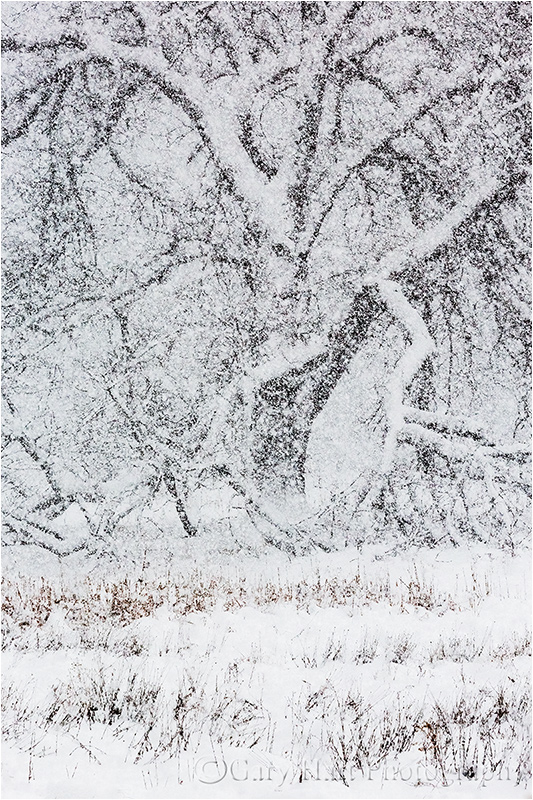

There’s a draft in here

Posted on December 13, 2013

Drafting an image

Few writers create a polished piece of writing in a single pass—most start with a draft that gets refined and tightened until it’s ready for publication. It’s an incremental process that builds upon what’s already been done. As somebody who has been writing and taking pictures for a long time, I’ve found a real connection between the creation process of each craft. The most successful photographers aren’t afraid to create “draft” images that move them forward without necessarily delivering them all the way where they want to be.

When I write a blog, I start with an idea and just go with it. But before clicking Publish (or Delete), I read, revise, then re-read and re-revise more times than I can count. Likewise, when I find a scene that might be photo-worthy, I expose, compose, and click without a lot of hand wringing and analysis. But I’m not done after that first click, and I don’t particularly care if it’s not perfect. When my initial (draft) frame is ready, I pop the image up on my LCD, evaluate it, make adjustments, and click again, repeating this cycle until I’m satisfied, or until I decide there’s not an image there. (In the days before digital, the same evaluation process took place through the viewfinder with my camera on a tripod.)

Another tripod plug

It’s the tripod that makes this shoot/critique/refine process work. Much the way a computer allows writers to save, review, and improve what they’ve written (a vast improvement over the paper/pen or typewriter days), a tripod holds your scene while you decide how to make it better. Photographing sans tripod, I have to exactly recreate the previous composition before making my adjustments. But using a tripod, when I’m finished evaluating the image, the composition I just scrutinized is waiting for me right there atop my tripod, allowing each frame to improve on the previous frame.

About this image

Composition isn’t limited to the arrangement and framing of elements in a scene—it can also be the way the image handles depth and motion. For example, living in California, I just don’t get that much opportunity to photograph falling snow. So, on last week’s visit to Yosemite, when I saw the Cook’s Meadow elm tree partially obscured by heavy snowfall, I knew an image was in there, but wasn’t quite sure how to best render the millions of fluttering snowflakes between me and the tree. What shutter speed would freeze (pun unavoidable) the falling flakes, and what depth of field would best convey the falling snow? Would too much DOF be too cluttered? Would not enough DOF be too muddy?

But before solving those problems, I needed a composition. I started with my original vision, a tight, horizontal frame of the tree’s heavy interior—my “draft” image. With my camera on my tripod I tried several successively wider frames, each a slight improvement of the previous one, before jettisoning my tight horizontal plan in favor of a wider vertical composition. Though I knew right away I was on the right track, it still took a half dozen or so incrementally better frames before finally arriving at the composition you see here.

With my composition established, I set to work on the depth and shutter speed question. As good as the LCD on my camera is, I didn’t want to be making those decisions based on what I saw on a credit card size screen, but my tripod enabled me to capture a series of identically framed images, each with a different f-stop and shutter speed. Back home on my computer, I was able compare them all to one and other without being distracted by minor framing differences. I finally decided I like the version with lots of depth field.

Category: How-to, Photography, snow, Yosemite Tagged: Photography, snow, winter, Yosemite

Dashing to the snow

Posted on December 9, 2013

Winter Reflection, Half Dome and the Merced River, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/13 second

16mm

ISO 100

F16

If there’s anything on Earth more magical than Yosemite with fresh snow, I haven’t seen it. The problem is, Yosemite Valley doesn’t get tons of snow—its relatively low elevation (about 4,000 feet) means the valley often gets rain when most of the Sierra gets snow. And when snow does fall here, it doesn’t stay on the trees for more than a few hours (if you’re lucky). Which is why I’ve always said the secret to photographing snow in Yosemite is to monitor the weather reports and time your visit to arrive before the storm. This strategy gives photographers within relatively easy driving distance, especially those of us without day job, a distinct advantage—from my home in Sacramento I can be in Yosemite Valley in less than four hours (that’s factoring a Starbucks stop in Merced and a fill-up in Mariposa), and I have no problem using darkness to make the roundtrip on the same day.

So last week, when the National Weather Service promised lots of snow in Yosemite for the weekend, I quickly freed up my Saturday. I usually stay just outside the park in El Portal, but because I didn’t want to risk being turned away by a (rare but not unprecedented) weather related park closure, I booked Friday and Saturday nights at Yosemite Lodge, right in the heart of Yosemite Valley—even if the roads shut down, from there I’d be able to walk to enough views to keep me happy all day.

I arrived in the dark to find lots of ice and patches of crusty old snow; I woke dark-and-early Saturday morning to about ten inches of fresh snow. Yippie! The snow fell intermittently throughout the day, with conditions ranging from nearly opaque to classic Yosemite clearing storm drama. Since I was by myself, I was able to deemphasize many of the most frequently photographed spots my workshop expect to photograph and explore random scenes along the Merced. In the morning I concentrated on El Capitan scenes; the afternoon was more about Half Dome.

Of course the classic views are that way for a reason, so, as you can see in this image, I gave them some attention to. Despite not being much of a tourist location, many photographers know about this scene just upstream from Sentinel Bridge. It’s a little hard to find, but usually fairly accessible. But this time getting there forced me to employ a creative parking strategy and to soil about one hundred yards of virgin powder. At this spot a couple of weeks ago I used a telephoto to isolate a single tree clinging to its fall color and reflecting in the river; this visit was my widest lens that got all the work.

The January issue of Outdoor Photographer will include my Yosemite El Capitan Winter Reflection image and a paragraph explaining how to photograph snow in Yosemite Valley. Here’s pretty much what I say there, with a little elaboration:

- Arrive in Yosemite Valley before the storm and plan to stay until it’s over. Getting there before the snow starts makes your life so much simpler; staying until the storm passes not only gets you the coveted “clearing storm” images, it also allows you to photograph all of Yosemite’s iconic features above a snow-covered landscape.

- Despite what Google Maps, your GPS, or your brother-in-law tell you, don’t even think about any route that doesn’t take you through Mariposa and up the Merced River Canyon on Highway 140. The highest point on 140 is Yosemite Valley; all other routes into the park go over 6,000 feet and are much more likely to be icy, closed, or require chains. For people coming from the north that means 99 to Merced and east on 140. Coming from the south, you can either take 99 to Merced (easier) and 140, or 41 to Oakhurst and 49 to Mariposa (faster).

- Carry chains. While you’re rarely asked unless weather threatens, every car entering Yosemite in winter is required to carry them, even 4WD. While 4WD is usually enough to avoid putting chains on, that’s not a sure thing. And if you get caught in a chain check without them, you’re parked right there until the requirement is lifted. If you’re driving your own car to Yosemite, bite the bullet and purchase chains. If you’re flying into California and renting a car, try to get 4WD and keep your fingers crossed that you don’t get asked. Some people will purchase chains and try to return them if they didn’t use them, but that can be risky so check the store’s chain return policy.

- Don’t hole-up in your room while it’s snowing. I generally circle the valley looking for scenes (about a 30 minute roundtrip). If the low ceiling has obscured all the views and you tire of photographing close scenes, park at Tunnel View and wait. Not only is Tunnel View the location of some of Yosemite’s most spectacular clearing storm images, it’s also the first place storms clear. And because you’ll be stunned by how fast conditions in Yosemite can change, waiting at Tunnel View is the best way to avoid missing anything. Another advantage Tunnel View offers is its panoramic view of the entire valley that helps you to decide where to go next. For example, from Tunnel View you can see if Half Dome is emerging from the clouds and there are probably nice images to be had on the east side, or if your best bet will be to stay on the west side and concentrate on El Capitan, Bridalveil Fall, and Cathedral Rocks.

- No matter how spectacular the view is where you are now, force yourself to move on after a while because it’s just as spectacular somewhere else. Trust me.

Category: Half Dome, How-to, Merced River, reflection, Yosemite Tagged: Half Dome, Photography, reflection, snow, Yosemite

Made in the shade

Posted on December 2, 2013

Imagine that you want to send an eight-inch fruitcake to your nephew for Christmas (and forget for a moment that you’ve been come that relative), but only have a six-inch box. You could cut off one end or the other, squish it, or get a bigger box. If the fruitcake represents the light in a scene you want to photograph, your camera’s narrow dynamic range is the box. Of course the analogy starts to fall apart here unless you can also imagine a world where box technology hasn’t caught up with fruitcake recipes, but the point I’m trying to make is that whether it’s fruitcake or light, when you have too much of something, compromises must be made.

So, forgetting about fruitcakes for a moment, let’s look at this image of Bridalveil Creek in Yosemite. In full daylight on a sunny day the creek would have been a mix of sunlight and shade far beyond a camera’s ability to capture in a single frame—photographing it would have forced me to choose between capturing the highlights and allowing the shadows to go black, or capturing the shadows and allowing the highlights to go white. But photographing the scene in full shade compressed the dynamic range naturally, to something my camera could handle—suddenly everything was in shadow, and all I needed to do was keep my camera steady enough for the duration of the shutter speed necessary to expose the scene at the f-stop and ISO I chose.

This illustrates why “photographer’s light” is so different from “tourist’s light.” It also explains why your family gets so irritated when you base your vacation stops on when the light will be “right.” (Or, if you (wisely) defer to your family’s wishes, you get so frustrated that your vacation photos don’t look like the photos that show-off in your camera club submits for every competition.)

I love photographing a colorful sunset as much as the next person, but I’m never happier as a photographer than when I’m able to play with a pretty scene in full shade. Overcast skies are great because they allow me to photograph all day, but because clouds are never a sure thing, at every location I photograph I try to have weather-independent spots that will allow me to photograph when clear skies fill the rest of the landscape with sunlight. For example, Bridalveil Creek—nestled against Yosemite Valley’s shear south wall, much of the year Bridalveil Creek is in full shade until at least mid-morning, and then again by mid-afternoon. I never have to worry about what the light is here because I know exactly when I’ll find it in wonderful, (easy) low contrast shade.

The morning I captured this image was one of those blue sky days that can shut a photographer down, but I knew exactly where I needed to be. Arriving at about 8 a.m., I had several hours of shooting in easily manageable, constant light. As I scrambled up the creek toward the fall, I fired off a few frames but nothing stopped me until I came across this small pool swarming with recently fallen leaves. A couple of “rough draft” frames were enough to know that there was an image in here—I just needed to find it.

I suspected I needed to be closer, but between the large, slippery rocks and frigid creek, movement was quite difficult. Nevertheless, with each composition I seemed to manage to work my way a little closer, until I finally found myself at water’s edge. I started my composition at eye level, but that gave me too much water. To better balance the background cascade, middle-ground pool, and foreground leaves, I dropped down to about a foot above water level—this allowed me to include the foreground leaves with a telephoto that brought the cascade closer and shrunk the water separating the two.

Framing the scene this way required zooming to 60mm; because I wanted as much sharpness throughout the frame as possible, I stopped all the way down to f22 (an extreme I try to avoid). While the dense shade made the scene’s dynamic range manageable, it also made it quite dark; adding a polarizer to cut the glare subtracted two more stops. Sometimes I can increase my ISO enough to achieve a shutter speed that gives a little definition in the water, but given all the other exposure factors I just cited, my water was going to be blurred no matter what ISO I chose. So I decided to go the other direction and maximize my shutter speed to emphasize the motion of the leaves swirling on the pool’s surface.

* * *

FYI, your nephew would probably prefer an Amazon gift card. And if you must send a fruitcake, this one looks good (feel free to try it and send a sample).

Category: Bridalveil Creek, fall color, How-to, Humor, Yosemite Tagged: autumn, fall color, Photography, Yosemite

Moon chasing: The rest of the story

Posted on November 19, 2013

Moon!, Half Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/13 second

F/11

ISO 200

400 mm (slightly cropped)

Wow, it seems like only yesterday that the moon was just tiny dot hovering above Half Dome.

What happened?

No, the moon didn’t magically expand, nor did I enlarge it digitally and plop it into this image. What happened is that I waited two days and moved back; what happened is the difference between 40mm and 400mm; what happened is a perfect illustration of the photographer’s power to influence viewers’ reaction to a scene through understanding and execution of the camera’s unique view of the world.

The rest of the story

My workshop group captured the “small” moon at sunset on Thursday, when it was 93% full and the “official” (assumes a flat, unobstructed horizon) moonrise was 3:09 p.m (an hour and 40 minutes before sunset). That night the moon didn’t rise to 16 degrees above the horizon, the angle to Half Dome’s summit as viewed from our location beside the Merced River, until almost exactly sunset. Because it’s so much higher than anything to the west, Half Dome gets light pretty much right up until sunset—look closely and you can see the day’s last rays kissing Half Dome’s summit.

Flat horizon moonrise on Saturday, when the moon was 100% full, was at 4:24 p.m., only about twenty minutes before sunset. But Tunnel View is nearly 500 feet above Yosemite Valley; it’s also 5 1/2 miles farther than Half Dome than Thursday’s location—this increased elevation and distance reduces the angle to the top of Half Dome to just 6 degrees. So, despite rising over an hour later, when viewed from Tunnel View, the moon peeked above the ridge behind Half Dome just a couple of minutes after sunset (if we’d stayed at Thursday night’s location, in addition to being hungry and cold, by Saturday we’ have had to wait until after 6:00 for the moon to appear).

Exposure

My objective for full moon photography is always to get the detail in the moon and the foreground. As I mentioned in yesterday’s post, these were workshop shoots, and experience has shown me that the most frequent failure when photographing a rising moon in fading twilight is getting the exposure right—the tendency is to perfectly expose the foreground, which overexposes the daylight-bright moon (leaving a pure white disk). This problem is magnified when the moon catches everyone unprepared.

So, both evenings I had my group on location about 30 minutes before the moon. While we waited I made sure everyone had their blinking highlights (highlight alert) turned on, and understood that their top priority would be capturing detail in the moon. I warned them that an exposure without a blinking (overexposed) moon would slightly underexpose the foreground. And I told them that once they had the moon properly exposed (as bright as possible without significant blinking highlights), they shouldn’t adjust their exposure because the moon’s brightness wouldn’t change and they’d already made it as bright as they could. This meant that as we shot, the foreground would get continually darker until it just became too dark to photograph.

(A graduated neutral density filter would have extended the time we could have photographed the scene, but the vertical component of Yosemite’s horizon made a GND pretty useless. A composite of two frames, one exposed for the moon and one exposed for the landscape would have been a better way to overcome the scene’s increasing dynamic range.)

Compare and contrast

Winter Moonrise, Half Dome, Yosemite

Thursday night’s scene, which would have been beautiful by itself, was simply accented by the (nearly) full moon. Contrast that with my visit a few years ago, when I photographed a full moon rising slightly to the left of its position last Saturday’s night. But more significant than the moon’s position that evening was the rest of the scene, which was so spectacular that it called for a somewhat wider composition that included the pink sky and fresh snow. And then there’s the above image, from last Saturday night—because the sky was cloudless (boring), and snow was nowhere to be seen, I opted for a maximum telephoto composition that was all about the moon and Half Dome.

The wide angle perspective I chose Thursday night emphasized the foreground by exaggerating the distance separating me, Half Dome, and the moon; the snowy moonrise image found a middle ground that went as tight as possible while still conveying the rest of the scene’s beauty. Saturday night’s telephoto perspective compressed that distance, bringing the moon front and center. Same moon, same primary subject: If Thursday night’s moon was a garnish, Saturday’s was the main course.

Learn more about photographing a full moon

Join me next fall as we do this all over again

A gallery of Yosemite moons

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About