Blinded by the light

Posted on March 29, 2014

Sometimes we’re so focused on the spectacular, we overlook the sublime

Upper Antelope Canyon near Page, Arizona, is known for its brilliant light shafts that seem to originate from heaven and streak laser-like through open air to spotlight the canyon’s red sandstone walls and dusty floor. Sometimes multiple shafts are visible, ranging from pencil thin to tree-trunk thick. The rare combination of conditions the shafts require include clear skies and the high sun angle only possible midday on the long side of the equinoxes. The shafts also require airborne dust—easily stirred by wind or footfall, but often augmented by the Navajo guides who carry plastic scoops to toss the powdery particles skyward.

Photographers from around the world flock to Page each spring and summer, packing Upper Antelope Canyon like Manhattan subway commuters in hopes of capturing their version of this breathtaking phenomenon. Given the crowds, it would be an understatement to say that the experience isn’t as inspiring or peaceful as the photos make it appear. But it is mesmerizing, so much so that when the beams fire, it’s difficult to concentrate on anything else. And therein lies the rub—the color, curves, and lines that are Antelope Canyon’s essence are overpowered its most famous quality.

The only way to get access to Upper Antelope Canyon is to join a tour led by a Navajo guide (I’ve never had a bad guide). The photo tour (as opposed to the standard, shorter “tourist” tour) of Upper Antelope gets you two hours in the canyon—one hour to photograph the beams in the company hundreds of oblivious tourists and competing, desperate photographers, and a second hour once the canyon has emptied, when it’s possible to walk its one hundred or so yards in relative peace and appreciate the qualities that make Antelope Canyon special.

As cool as the light shafts are, it’s this quiet hour that I’ve come to enjoy most, both as a photographer and as a lover of all things natural. Without the shafts hypnotic pull, I’m free to appreciate light’s interaction with Mother Nature’s handiwork. Layered sandstone carved by centuries of sudden, violent flash floods separated by months of arid heat. The floods have scoured the hard walls smooth, crafted narrow twists and broad rooms, and finished the walls with multifaceted curves and lines that reflect sunlight in all angles like a house of mirrors. Each ray of light entering from the extremely narrow opening at the ceiling is reflected at least once, and usually many times before reaching its viewer’s eyes (or camera). Shaded sections create dark frames for the illuminated sections that seem to glow with their own light source. As the light shifts or the viewer moves, shapes appear—a face, a bear, a heart—and disappear to replaced by new shapes limited only by the viewer’s imagination.

The bifurcated Antelope Canyon experience exposes an important reality: Dramatic light and color can blind viewers to a scene’s true beauty. While brilliant light and vivid sunsets grab your eyes in much the same way a rich dessert immediately satisfies your taste buds, we can’t live forever on this visual dessert. The images that sustain, the ones that draw us back and hold our attention once we’re there, are more often the subtle explorations of indirect light that allow us to make our own discoveries.

* * *

Read more about photographing Antelope Canyon

* * *

Antelope Canyon Gallery

- Rock Face, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Glow, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Focused Beam, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Twin Beams, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Inner Glow, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Beam, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Divine Spotlight, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

- Nature’s Cathedral, Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona

My photography essentials, part 3

Posted on March 23, 2014

A couple of weeks ago the editors at “Outdoor Photographer” magazine asked me (and a few other pros) to contribute to an upcoming article on photography essentials, and it occurs to me that my blog readers might be interested to read my answers. Here’s how I answered the third of their three questions:

What three things contribute to keeping you inspired, energized and creative on your shoots and why does each keep you inspired, energized and creative?

- When I’m photographing a particularly beautiful moment—such as a moonrise over Yosemite, lightning and a rainbow at the Grand Canyon, or the Milky Way I force myself to turn off my photographer brain and for a few minutes just become a regular human who might be witnessing the most beautiful thing happening on Earth at that moment. The sense of appreciation and marvel is a vital connection to my subjects that fuels my photography.

- Throughout the year I plan excursions that keep me motivated: Each spring I’m recharged by drives through the Sierra foothills and its rolling green hills, studded with poppies and oak trees and cut by brimming creeks and rivers, that just beg to be photographed. My calendar is loaded with the days I’ll find a crescent moon dangling in the amber/blue transition separating night and day. And nothing exhilarates me more than a dark sky dotted with stars. Since so much of my photography time is spent guiding others to my favorite locations (at my favorite times), these personal trips establish an essential balance in my life.

- And most of all, I’m inspired by viewing the work of other photographers:

- Ansel Adams is an obvious inspiration—not only was he a great photographer, Adams navigated uncharted territory to pave the way for all who followed. I chuckle when other photographers defend their captures with, “That’s the way it really looked,” because Adams’ absolute connection with his camera’s reality, and the synergy between his capture and processing, proved that duplicating human (visual) reality is absolutely not a nature photographer’s goal.

- Galen Rowell is another inspiration, for his understanding of light, his obsessive inquisitiveness, and his willingness to explore photography’s physical and mental boundaries. Rowell possessed a synergy between his brain’s creative and logical capabilities—an ability to understand, anticipate, and calculate, combined with an instinctive ability to turn all that off and simply create. From him I learned to follow the light to the exclusion of all distractions, no matter how tempting.

- David Muench, was an influence long before I entertained thoughts of becoming a photographer. I have memories dating back to my childhood of paging through Muench’s massive coffee-table books and being awed by the beautiful scenes he’d witnessed. At the time I had no idea of how much skill those images required—I just thought he was incredibly lucky to have been there to see it. Of course now I appreciate Muench’s unique ability to see and manage the front-to-back aspect of a scene to create the illusion of depth, an approach I’m now convinced was made easier for me by a lifetime of exposure to those images.

- Charles Cramer’s meticulous compositions extract beauty from simple scenes and subtle light and can transfix me for hours. Each of Cramer’s images feel to me like personal discoveries, as if he’s uncovered nature’s true beauty while everyone else’s camera was pointed in the other direction. Browse his galleries and note how many images use indirect light and no sky. More than any other photographer, Charles Cramer’s images inspire me to grab my camera and run outside.

About this image

On every visit to Hawaii’s Big Island I visit this unnamed beach on the Puna coast south of Hilo. I’ve photographed it in a variety of dramatic conditions: colorful sunrises and sunsets, crashing surf, rainbows, but this nearly monochrome image beneath heavy gray clouds is my favorite.

In addition to the color and light, the scene varies greatly with the tide and surf. This morning, finding pillows of basalt cradling still pools that reflected the morning sky, I dropped low and moved close with a wide lens to fill my foreground. Working in shadowless, pre-sunrise light, I used a long exposure to smooth the water and create a serenity to more closely matched my state of mind.

My photography essentials, part 2

Posted on March 17, 2014

A couple of weeks ago the editors at “Outdoor Photographer” magazine asked me (and a few other pros) to contribute to an upcoming article on photography essentials, and it occurs to me that my blog readers might be interested to read my answers.Here’s my answer to the second of their three questions:

What are your three most important non-photo pieces of gear that you rely on for making your photographs and why do you rely on each of the three?

- How did I ever get by without a smartphone? Among other things, and in no particular order, it keeps me company on long trips (that are often far off the grid), informs, entertains, guides, provides essential sun and moon rise/set time and location, helps me choose the best f-stop, allows me to manage by business from any location, and even gives me traffic and weather warning. My iPhone (there are many similarly great Android and Windows phones) is 64GB (the largest available) to allows plenty of room to store maps, more podcasts than I can listen to on a single trip, and a lifetime worth of music. Of course a smartphone is be of little value without its apps. When choosing apps, a primary requirement is usability without Internet connectivity. My favorite connection-independent apps are: Focalware, for sun/moon info for any location on Earth; Depth of Field Calculator by Essence Computing, for hyperfocal info; and Theodolite, for general horizon and direction angles (among other things). I also make frequent use of the Dropbox Favorites option, which allows me to pre-download any file for review when I’m not connected.

- My dash-top GPS is compact enough to slip into any suitcase (there are many viable options; while I use Garmin, interface frustrations stop me short of endorsing it). Because I visit many distant locations that I’m not able to return to as frequently as I’d like, I save every potential photo spot in my dash-top GPS. For example, there are usually many months between my Hawaii visits. Over the years I’ve found far more incredible spots to photograph than my feeble brain can retain. But traveling with a GPS, I don’t have to re-familiarize myself with anything—I just pop it on my dash before driving away from the airport and instantly navigate to my locations like a native. (Or to the nearest Starbucks.)

- Here’s a just-discovered non-photo essential that didn’t get passed on to “Outdoor Photographer”: After many, many years of trying to find a hands-free way to communicate on my long drives in the middle of nowhere, my new Plantronics Voyager Legend bluetooth earpiece feels like a godsend. Wired earbuds get tangled and have lousy noise cancellation; sound quality makes bluetooth radio connections virtually unusable. And I’ve lost track of the number of earpieces I’ve discarded for some combination of discomfort, poor receiving sound quality, poor sending sound quality, and lousy battery life. I can wear my Voyager Legend for hours and forget it’s there; I can answer calls without taking my eyes off the road; and most importantly, I can hear and be heard as if I’m sitting in a quiet room.

About this image

My GPS guided me to this remote, wildflower-dotted hillside, discovered the previous spring and now a regular destination on my annual spring foothill forays. The wildflower bloom varies greatly each year, so without the GPS sometimes it’s impossible to know whether I’ve found a spot that thrilled me the year before. In this case I found the bloom everything I dared to hope.

Rather than pull out my macro lens, I twisted an extension tube onto my 100-400 lens and went to work. Since there were virtually no shadows, the dynamic range wasn’t a problem, despite the bright, direct sunlight. Metering on the brightest part of the scene and underexposing by about one stop (about 2/3 stop above a middle tone) prevented the brightest highlights from washing out and saturated the color.

Most of my attention that afternoon went to the poppies, but here I concentrated on a group of small, purple wild onions and let the limited depth of field blur the poppies into the background. Clicking the same composition at a half dozen or so f-stops from f5.6 to f16 allowed me to defer my depth of field selection until I could view my images on my large monitor.

My photography essentials, part 1

Posted on March 11, 2014

Morning Light, Yosemite Falls from Sentinel Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

1/50 second

F/16

ISO 400

105 mm

A couple of weeks ago the editors at “Outdoor Photographer” magazine asked me (and a few other pros) to contribute to an upcoming article on photography essentials, and it occurs to me that my blog readers might be interested to read my answers. Here’s my answer to the first of their three questions:

1. What are the top three most important pieces of photo gear for you to create your particular style of landscape photography and why is each important?

(Since we all need cameras and lenses, I stuck to optional items.)

- At the top of my list, and it’s not even close, is a tripod/ball-head combo that’s easy to use: sturdy, light, and tall enough to use without a (destabilizing) center post. More than just a platform to reduce vibration, my tripod is a compositional aid that allows me to click a frame, evaluate my image, refine my composition and exposure settings, and click again. I often repeat this process several times until I’m satisfied. Using a tripod, the composition I’m evaluating is sitting right there, waiting for my adjustments; without a tripod, I need to recreate my composition each time. Another unsung benefit of the tripod is the ability to make exposure decisions without compromising f-stop or ISO to minimize hand-held camera shake. I’m a huge fan of Really Right Stuff tripods and heads.

- Adding an L-plate to my bodies was a game-changer—not only does it make vertical compositions more stable, they’re closer to eye level and just plain easier. In my workshops I often observe photographers without an L-plate resist vertical oriented shots, either consciously or unconsciously, simply because it’s a hassle to crank their head sideways, and when they do they need to stoop more. And some heads are not strong enough to hold a heavy, vertically oriented camera/lens combo. But since switching to the L-plate, my decision between a horizontal or vertical composition is based entirely on the composition that works best.

- Given the amount of travel I do, not to mention the hiking once I get there, I need a camera bag that handles all my gear (including my tripod and 15” laptop), has room for extra stuff like a jacket, water, and food, is comfortable for long hikes, durable, easy to access, and (this is huge) fits all airline overhead bins. I’ve tried many, and the F-stop Tilopa is the only one I’ve found that meets all my criteria.

* * *

Because people always seem interested in the equipment I use

For what it’s worth, I have relationships with a few photo equipment vendors that allows them to use my name, and in return I get a price break on their equipment. But I’ve never been one to play the endorsement card to great benefit, or too allow the whole freebie/discount thing affect my recommendations. For example, I’d never heard of F-Stop Gear when they asked if I’d like to be one of their staff pros. When they offered to send me a bag to try, I made it very clear that I’d only use or endorse it if I liked it better than anything else I’ve tried, but they sent it anyway, no strings attached. I’m happy to say that I absolutely fell in love with my F-Stop Tilopa, and haven’t used another bag in over three years (before that I used different bags for different needs).

Likewise, I used (and sung the praises of) Really Right Stuff heads and L-plates long before RRS had ever heard of me. I own four Gitzo tripods, and while I think they’re great, I have to say that my new Really Right Stuff tripod (TVC-24L) is demonstrably better—lighter, sturdier, and easier to use—than my Gitzo 3530LS. And I’ve always found RRS customer service second to none.

Now if I could only get Apple to notice me….

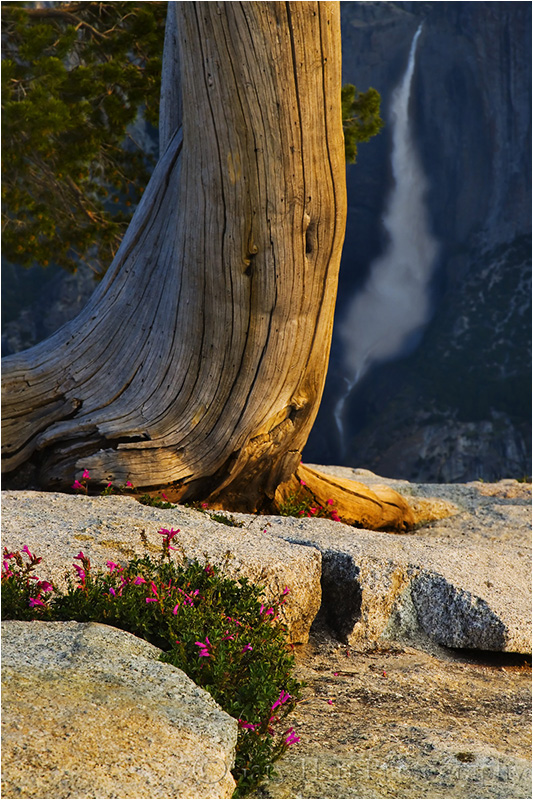

About this image

Follow the light. Here atop Sentinel Dome it would have been easy to concentrate on one or more of a variety of dramatic subjects, including El Capitan, Yosemite Falls, Half Dome, and Cathedral Rocks. But the best light this morning was the warm sunrise glow on an anonymous tree and a clump of wildflowers.

I’d spent the night in the back of my truck a few miles down the road from the Sentinel Dome trailhead. The hike is only about a mile—it’s relatively easy in daylight, but I wanted to be atop the dome about 45 minutes before sunrise, so I did the whole thing in the dark (not something I’d recommend unless you’re extremely familiar with the trail, as I was). Since this was late June, sunrise was around 5:30, which meant an extremely early morning. As it turned out, the sunrise, while magnificent to experience, wasn’t terribly noteworthy photographically.

As I started my walk back to my truck, the light on this tree stopped me. I positioned myself to align the wildflowers, tree, and Yosemite Fall, moving as far back as I could to allow a telephoto that would compress these three primary elements. I dropped low and focused to emphasize the wildflowers and weathered tree in the warm light, relegating unlit Yosemite Falls to background status by allowing it to go slightly soft.

It’s Greek to me

Posted on March 3, 2014

Photograph: “Photo” comes from phos, the Greek word for light; “graph” is from graphos, the Greek word for write. And that’s pretty much what we photographers do: Write with light.

Because we have no control over the sun, nature photographers spend a lot of time hoping for “good” light and cursing “bad” light. There’s no universal definition of good and bad light; it’s usually more a function of whatever it is we want to do at the moment. Just as portrait photographers have complete understanding of the artificial light they use to illuminate their subjects, nature photographers should understand the sunlight they photograph: what it is, what it does, and why it does it.

It’s this understanding of light that allows me to be in the right place for vivid sunrises and sunset, to know the best time and location for blurring water, and that helped me anticipate this amazing rainbow. To learn more about light, read the Light article in my Photo Tips section.

About this image

May 26, 2009

On my drive to Yosemite the sky above the San Joaquin Valley was clear, but I was encouraged to see dark cumulus clouds billowing above the Sierra to my east. Sierra thunderstorms in May are rare, but not unprecedented. At the very least I knew the clouds would make for interesting photography. As I entered the park via Big Oak Flat Road, a few large drops dotted my windshield. The afternoon sun was now obscured by clouds, but the sky to the west remained virtually cloudless, a good sign, but nothing I hadn’t seen before.

By the time I reached Yosemite Valley the rain had increased enough to require me to engage my wipers and get my mental wheels turning. I was in the park for a one day, private photo tour with a couple from Dallas. The arrangement was to meet at Yosemite Lodge for dinner to plan the next day’s activities, then to go shoot sunset. As I continued toward my appointment I allowed myself to consider the possibility of a rainbow. Going for it would require rushing to meet my customers, delaying dinner, and possibly sitting in the rain with no guarantee of success.

Still undecided but with about 20 minutes to spare, I dashed up to Tunnel View to survey Yosemite Valley. I liked the way things were shaping up; if I’d have been by myself I’d have skipped dinner. Leaving Tunnel View I continued surveying the sky—by the time I reached the lodge I knew I could be sued for malpractice if I didn’t at least suggest the possibility of a rainbow.

We completed our introductions in front of the cafeteria, but before entering I suggested that maybe we should forget dinner for now. Robert and Kristy were as excited about the conditions as I was (phew) but had just completed a long hike and were famished, so we rushed in and grabbed pre-made pizzas to eat on the road.

Twenty minutes later we were sitting on my favorite granite slope above Tunnel View. We were immediately greeted by a flash of lightning, followed not too many seconds later by a blast of thunder. As a lifelong Californian, I’m not particularly experienced with lightning, so I deferred to the Texans and found comfort in their lack of concern (knowing what I know now, I probably should have been more concerned).

Rainbow photography is equal parts preparation and providence. The preparation comes from understanding the optics of a rainbow, knowing the conditions necessary, where to look, then putting yourself in the best position to capture it; the providence is a gift from the heavens, when all the conditions align exactly as you envisioned. Robert, Kristy, and I had been admiring the view and photographing intermittently in a light, warm rain for about thirty minutes when a rainbow appeared. It started slowly, as a faint band in front of El Capitan, and quickly developed into a vivid stripe of color. For the next seven minutes we shot like crazy people—I varied my compositions with almost every shot and called to them to do the same. When it ended we were giddy with excitement—never let it be said that a professional nature photographer can’t get excited about his subjects—and even though the rainbow never quite achieved a complete arc across the valley, it had been everything I dared hope for.

Little did we know that this first rainbow was just a prelude—less than ten minutes later a second rainbow appeared, becoming more vivid than the first, growing into a full double rainbow that arced all the way across Yosemite Valley, from the Merced River to Silver Strand Fall. It lasted over twenty minutes, long enough for me to set up a second camera and do multiple lens changes on each. We actually reached the point where we simply ran out of compositions and could only laugh as we continued clicking anyway.

One more thing: This is the third time I’ve processed this image. I’ve never been completely happy with some of the color tones and overly bright highlights, so I decided to give it one more shot. Using Lightroom 5 and Photoshop CS 6, I was finally able to come up with something that more accurately represents the experience of this unforgettable moment.

Workshop Schedule

A Gallery of Rainbows

A rite of spring

Posted on February 26, 2014

Today it’s gray and wet in Sacramento, a refreshing break from our ridiculously warm and dry winter (sorry, pretty-much-everywhere-else-in-the-U.S.). Usually by the end of February my thoughts have turned to spring, but this year I find myself feeling a cheated of winter (and wishing the rest of you would have shared). As miserable as it can be, I’ve always loved winter photography—not just snow (which I have to travel to see), but rain, clouds, bare trees, and the low angle of the sunlight.

Another aspect of winter I like is the precipitation that rejuvenates our creeks and rivers and nourishes the wildflowers. It’s hard to know what combination of winter conditions will make a good wildflower spring, but I do know that ample rainfall is an important component. Which makes me a little nervous about the wildflowers’ prospects this spring. But that won’t stop me from what has become an annual ritual, meandering through the foothills east of town, Spring Training baseball on the radio (go Giants!), photographing poppies. I have several go-to poppy spots, but I’m easily distracted and often never make it to my original destination.

The image here is from one of my earliest spring excursions, nearly ten years ago. On my way home, I detoured at the last minute to a spot I knew I’d find a few nice poppies—(believe it or not) the Intel parking lot in Folsom. The poppies were in an elevated bed atop a retaining wall, allowing me to easily drop low and capture them backlit by the setting sun. The sun, distorted and dulled by horizon haze, was a throbbing orange ball that I blurred beyond recognition with an extension tube and a large aperture on my 100mm macro lens. Without wind, focus through my viewfinder on the center poppy’s leading edge was pretty easy (today I’d have used live-view focus). The translucent petals caught the fading sunlight, igniting the flowers like orange lanterns. I underexposed slightly to save the highlights and color, and to turn the shaded background into a black canvas.

One other thing I remember about this shoot was my brief brush with the law. Apparently my activity aroused the interest of Intel Security—after just a few minutes of shooting I was visited by an officer who clearly took his job quite seriously. It took me a few minutes, but I was finally able to convince him that, despite my sinister appearance, I was in possession of no explosive device, nor was I an AMD (Advanced Micro Devices, Intel’s leading competitor) spy seeking the secrets of Intel’s fertile flower bed. After making a theatrical display of checking of my license plate (that clearly communicated, “We know who you are”), and in a tone that made let me know he wasn’t quite convinced and would be watching me, he allowed me to finish.

- Poppy Hillside, Sierra Foothills

- Poppy Pastel, Sierra Foothills, California

- Champagne Glass Poppies, Merced River Canyon, California

- Poppy Lanterns, Merced River Canyon

- Brilliant Poppy, American River Parkway, Sacramento

- Spring, California Gold Country, Sierra Foothills

- Raindrops on Poppy, California Gold Country

- Poppies, Hite Cove Trail, Merced River Canyon

- Backlit Poppies, Folsom, California

- Poppy and Surf, Point Reyes National Seashore

- Sparkling Poppies, Merced River Canyon

- Poppies and Oak, Big Sur

Four sunsets, part four: Saving the best for last

Posted on February 23, 2014

Twilight Magic, Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

3 2/3 seconds

F/11.0

ISO 400

45 mm

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

- Read the second in the series here: Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

- Read the third in the series here: Four sunsets, part three: A marvelous night for a moondance

What I love most about photography is its ability to surprise me. Case in point: the final sunset of my recent Yosemite Horsetail Fall workshop, which delivered just one surprise after another.

I’d told my group that we’d get to photograph another moonrise on our last evening, but only if the clouds cooperated. And as the afternoon wore on, it seemed that the clouds that had cooperated so wonderfully all week wouldn’t be on our side tonight. Assembling everyone on the sloped granite above Tunnel View, I eyed the thin (and shrinking) strip of blue sky on the horizon above Half Dome and checked my watch: 5:10—in about fifteen minutes (less than ten minutes before sunset), with no clouds we’d see a full moon poke into view between Half Dome and Sentinel Dome. But our vantage point gave me a clear view of the clouds racing in that direction and our prospects weren’t good. Rather than stress (much), I stayed philosophical: We’d already had three fantastic sunset shoots, expecting a fourth would be downright greedy.

Nevertheless, it was fun to watch the clouds sprint across the sky and pile up behind Half Dome, changing the scene by the minute. Waiting there, I had thoughts about the throngs gathered on the valley floor, hoping (praying) for Horsetail Fall to light up. My group had been lucky on our first two sunsets, but tonight there’d been no sign of sunlight for at least thirty minutes, and with the cloud machine working overtime behind us, I was pretty certain the Horsetail crowd was in for disappointment.

Anticipating a moonrise, I’d gone up our vantage point with just my tripod, 5DIII, and 100-400 lens. Knowing exactly where the moon would appear, my composition was set well in advance—tight, with Half Dome on the far left and the moonrise point on the far right. But without the moon, I realized that the best shots would likely be wide, so I zipped back to the car and returned with another tripod (doesn’t everyone carry two?), my 1DSIII, and my 24-105. Sitting on the (cold) granite, a tripod on my left and my right, I quickly composed a wide shot with my new setup and resumed my vigilance.

By 5:25 I’d stopped watching the incoming clouds, which were streaming in faster than ever, and turned my focus to the moon’s ground-zero, willing the clouds to part for its arrival. At exactly 5:27 and as if by magic, the white glow of moon’s leading edge burned through the trees downslope from Sentinel Dome. I did a double-take—it was as if the moon had pushed the cloud curtain up and slipped beneath. I shouted, “There it is!” and the furious clicking commenced. We ended with about sixty seconds of moonrise, just long enough for the moon to balance atop the trees, before the clouds settled back into place and snuffed it out.

But the surprises had only just begun. While the whole group still buzzed about the moon, I noticed a faint glow on El Capitan. Not quite believing it (and not wanting to jinx anything), I kept my mouth shut and looked closer. But when the glow persisted, I had to point it out, if for no other reason than confirmation that I wasn’t hallucinating. Within seconds all doubts were dispelled as El Capitan exploded with light from top to bottom. So sudden and intense was the light that I’m surprised we didn’t hear the roar from the Horsetail Fall contingent in the valley below us. And rather than fade, as it often does, the light intensified, warming over the next couple of minutes from amber to orange to red. Soon the color deepened to an electric magenta and spread across the sky and all those clouds I’d been silently cursing just a few minutes earlier became allies, catching the color and reflecting it back to the entire visible world.

Giddy about the show, and focused on my two cameras, I’d long given the moon up for dead. So imagine my surprise when, just as the color reached a crescendo, there the moon was, burning through a translucent veil of clouds. So expansive was the scene that a telephoto couldn’t do it justice, so all of my images following the moon’s resurrection were captured with my 5DIII and 24-105. Exposure became trickier by the minute in the advancing darkness, and eventually, pulling detail from the valley without completely blowing out the moon required a 2-stop hard graduated neutral density filter.

Honestly, this was one of those moments in nature that no camera can do justice. I did my best to come find compositions that captured the majesty of Yosemite Valley, the vivid sky and the way it tinted the entire scene, and that Lazarus moon. But take my word for it, you just had to be there….

* * * *

Four Sunsets

- Revelation, Horsetail Fall, Yosemite

- Fire on the Mountain, El Capitan and Horsetail Fall, Yosemite

- Twilight Magic, Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View, Yosemite

Four sunsets, part three: A marvelous night for a moondance

Posted on February 19, 2014

Moondance, Half Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/5 second

125 mm

ISO 100

F11

How many Yosemite moonrise images are too many? I have no idea, but I’ll let you know as soon as I find out.

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

- Read the second in the series here: Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

5:10 p.m.

I stand on the bank of the Merced River, eyes locked on the angled intersection of Half Dome’s sharp northeast edge and its adjacent, tree-lined ridge. If the clouds cooperate, and I’ve done my homework right, a nearly full moon (96%) will be poking above this intersection any minute. We’d been fortunate the first two sunsets of my workshop; dare I hope for one more?

If the moonrise happens as I plan (hoped), the sight could rival what we’d gotten from Horsetail Fall on the first two nights of our workshop. But right now the sky behind Half Dome is smeared with thin-ish clouds—how thin I won’t know until the moon appears (or doesn’t). Gazing heavenward, I find it odd that a moonrise, something that can be predicted with such absolute precision, is so subject to weather’s fickle whim. And the clouds aren’t my only concern—just a half-degree error in my plotting would put the moon behind Half Dome and out of sight.

Few things in nature thrill me more than a moonrise. Camera or not, crescent or full, I love everything about a it: the obsessive plotting and re-plotting that gets me out there in the first place; the hand-wringing anticipation while I await the moon’s appearance; the first white pinprick of moonlight on the horizon (Is that it? There it is!); the ridge-top evergreens silhouetted against the rising disk; the glowing sphere hovering above the darkening landscape; and finally, the moonlit landscape beneath a star-studded sky. Everything.

So it shouldn’t surprise that virtually all of my photo trips—workshops and personal—are scheduled around the moon’s phase and some condition of the night sky. Sometimes I target a full moon, sometimes a crescent, and sometimes I want no moon at all (for dark skies that reveal the most stars)—the choice depends on the kind of moonrise and/or night photography I think best suits the landscape I’m traveling to photograph. But because this workshop is timed to coincide with the few February days that Horsetail Fall might turn a molten red at sunset, a calendar window I shrink even further to avoid the crowds that flock a little later in February, the moon is rarely a priority when I schedule the Horsetail Fall workshop. But I still check. And when I started planning my 2013 Yosemite Horsetail Fall workshop a couple of years ago, I was thrilled to discover that not only could I could time this trip for a full moon, I’d also be able to align that moon with Half Dome at sunset. Twice.

5:13 p.m.

I check my watch: 5:13. Sunset is 5:35; the moon should appear almost adjacent to Half Dome at about 5:15, then slowly rise, like a ball rolling uphill along Half Dome’s left side. By 5:30 the disk will have almost reached Half Dome’s summit, less than its own width with from the granite face. That is, if I’ve done my homework right. 5:14.

Any minute now….

I’d done all my figuring months in advance, which of course didn’t stop me from double-, triple-, quadruple-, and so-on-checking my results in the days leading up to my waiting beside the Merced River with a dozen or so other photographers. Part of my anxiety is the particularly fortuitous alignment of location, moon, and time that put the moon appearance above Half Dome right in my “ideal” sunset window as viewed from one of my favorite Yosemite locations. Not only does this spot provide a clear, relatively close view of Half Dome, it also is at a nice, reflective bend in the Merced River. Even without the moon this is a nice spot, end everyone in the group seems to be finding things to photograph. But I want the moon tonight. Really, really want the moon.

(You really don’t need to read this section)

My moonrise/set workflow was in place long before smartphones apps and computer software laid it all out for any photographer willing to look it up. But those tools are new tricks and I’m an old dog. So here’s how I’ve done it for years:

- Use my topo map software to determine the latitude and longitude of the location I want to photograph.

- Give my location’s latitude and longitude to my Focalware app (or, if I need the data to be a little more granular, the US Naval Observatory website), which returns the moon and sun rise/set altitude (degrees above a flat horizon) and azimuth (the angular distance relative to due north, from 0 to 360 degrees—imagine a clock: 12 is 0 degrees; 3 is 90 degrees; 6 is 180 degrees and so on).

- Next I plug the moon’s altitude/azimuth for my location into the plotting tool of my computer’s mapping software. This draws a line from my location (where I’ll be with my camera) to the location of the moonrise (or set). Most importantly, the line shows the moon’s alignment with whatever landscape feature I’m interested in (such as Half Dome). It also gives me both the distance and the elevation change between my location and the point above which it will rise.

- Finally, I use the elevation and distance data with the trig functions of a scientific calculator to get the altitude to which the moon must rise before it’s visible from my vantage point.

If this all sounds convoluted, that’s probably because it is. I suggest that you try something like The Photographer’s Ephemeris or Photo Pills, which does all this for you. But like I say, that’s a new trick….

5:15 p.m.

I squint, hoping to engage my x-ray vision enough to make out the moon’s outline through the clouds. Nothing. With conditions fairly static, the group has gotten their shots and is chatting more than clicking. Moon or not, the photography will improve as the light warms toward sunset. I walk uphill, away from the river and slightly upstream to improve my angle of view. Still nothing. (Did Ansel Adams experience this angst?)

We’ve reached the time that I expect the moon to appear. I’ve been plotting the moon long enough to be fairly confident within about one moon’s width (a half degree in either direction) of where it will rise, and within plus/minus two minutes of when it will rise. But the whether of seeing a moonrise depends on, well, the weather. Will rain, snow, or even just a rouge cloud shut us out? There’s really no way to know until the day arrives. And sometimes, for example this very instant, I can’t tell whether the sky will cooperate until I actually see the moon.

I’ve learned that the best time to photograph a full moon (when I say “full,” I often mean almost full, generally between 95 and 100 percent of the complete disk illuminated) is during a ten minute window straddling sunset. Much earlier and the light isn’t particularly interesting, and there isn’t enough contrast between the moon and the sky for the moon to stand out dramatically; much later and there’s too much contrast between the moon and everything else in the scene for the camera to handle.

Choosing this location introduces another unknown. Remember when I said that I can pinpoint the moonrise within about its width? Well, in this case that margin of error is just enough to give me pause, because rising slightly to the right of where I think it will rise puts the moon behind Half Dome until about five minutes after sunset. Sentinel Bridge, just a short distance downstream, would have been safer, but the Sentinel Bridge Half Dome shot is far more common, the bridge is usually teaming with people at sunset, and the moon would have been a little higher in the sky during “prime time.” So here we stand.

5:17 p.m.

What’s that faint white blob in the clouds? Without saying anything I squint and look closer. Sure enough, there it is, barely visible, less than one degree above the ridge (its rise above the ridge a couple of minutes ago must have been obscured by the clouds), pretty much where I expect it. Phew. I announce the moon’s arrival to the rest the group, but need to guide their eyes to it. As everyone’s attention returns to their cameras, I cross my fingers for the clear sky in its path to hang in there until at least sunset.

5:25-5:45 p.m.

The moon finally climbs above the clouds and I exhale. Still daylight bright, it now makes a striking contrast against the darkening sky. For the next fifteen minutes we shoot continuously, pausing only to recompose and monitor the highlights. Compositions, which I’d had everyone practice before the moon arrived, range from wide reflections that reduce the moon to a tiny accent, to tight isolations of the moon and Half Dome’s face.

As sunset approaches, the biggest concern becomes those lunar highlights—too small to register on the camera’s histogram, the moon’s face is easily blown out as we try to give the darkening foreground more light. Before we started I made certain everyone has engaged their camera’s Highlight Alert (“blinking highlights”) feature. They all know that when the moon starts flashing, they’ve reached the exposure threshold and must back off on their exposure and lock it in (a few “blinkies” are recoverable in Lightroom or Photoshop, but if the entire disk is flashing, the moon’s detail is probably lost for good)—while the moon will remain the same brightness (can’t take any more exposure), from that point on the foreground will continue darkening until it becomes too dark to photograph. Then we go to dinner.

Like everyone else, I used a variety of compositions. I already have a wide reflection image from a prior shoot, so the image I share here is a moderate telephoto—any tighter (to enlarge the moon further) would have truncated some of Half Dome’s face, something I just cant bring myself to do.

We finally wrapped up at about 5:45, when long exposures to bring out detail in the dark landscape made capturing detail in the bright moon impossible. Everyone was pretty thrilled at dinner, and even though the clouds thickened and washed out our planned moonlight shoot, there were no complaints. And little did we know, Mother Nature had concocted a grand finale for our final sunset.

Join me in Yosemite

PURCHASE PRINTS || PHOTO WORKSHOPS

A Gallery of Yosemite Moons

Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

Posted on February 16, 2014

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

While we’d been incredibly fortunate with our Monday night Horsetail Fall shoot, we didn’t get the molten glow everyone covets (though I’d argue, and several agreed, we got something better). Nevertheless, based on the relatively clear skies, I decided to take everyone back for one more try on Tuesday.

On Monday we’d been able to photograph in relative peace from my favorite spot on Southside Drive, but given that the weekend storm had left us in its rearview mirror, and that word had no doubt gotten out that Horsetail Fall was once again flowing, I guessed that the Horsetail day-trippers (Bay Area, Los Angeles, Central Valley photographers who cherry-pick there Yosemite trips based on conditions) would begin crowding into Yosemite Valley. To be safe, I got my group out there a little after 4:00 (sunset was 5:35). Despite being earlier, both parking turnouts were already teeming cars (if everyone squeezes, there might be room for fourteen legally parked cars)—just a few minutes later and we’d not have found room for our three vehicles (all the late arriving cars that had attempted creative, shoulder parking solutions returned to find parking tickets decorating their windshields). With so many more cars, I wasn’t surprised to find my preferred spot down by the river was already starting to fill—but we spread out a bit and everyone managed to squeeze in.

Unlike Monday evening, the Tuesday sky started mostly clear, with only an occasional wisp of cloud floating by. While the scene lacked the drama of Monday, the clear skies boded well for the fiery show we were all there for. We watched the crisp, vertical line separating light and shadow advance unimpeded across El Capitan. The mood was optimistic—borderline festive. Then, a little after five, with no warning the light faded and El Capitan was instantly reduced to a homogeneous, dull gray. Many people reacted as if their team had fumbled on the two yard-line, but those of us who know Horsetail Fall’s fickle disposition just smiled.

In all the years I’ve been photographing Horsetail Fall, I’ve come to recognize how much it likes to tease—while this is more of a gut feeling, it has always seemed to me that the evenings when the shadow marches without pause toward sunset, the light is much more likely to extinguish right before the prime moment. On the other hand, my best success seems to come on the evenings when the light comes and goes, teasing viewers right up until it suddenly reappears in all its crimson glory just before sunset. So, until the light disappeared I was a little concerned that things were going too well. But when the light faded I was able to guide them away from the ledge and reassure them that there’s no reason to panic just yet. And sure enough, about ten minutes later the sunlight came flooding back and everyone exhaled.

As shadow advances from the west, the remaining light warms—by 5:25 it had reached a rich amber. Once it reaches that stage my advice to everyone was that, since the show will either get better (more red) or worse (the light snuffed), and there’s no way of telling which it will be, they should just keep shooting until the light’s gone. And that’s what we did. At first there were no clouds and my composition was fairly tight to eliminate the boring sky. Then, just a few minutes before the “official” 5:35 sunset (I should add that “sunset” when you see it published refers to the time the sun sets below a flat horizon—it set far earlier for those of us on the valley floor, and it wouldn’t set on elevated Horsetail Fall until nearly 5:45), a nice cloud wafted up from behind El Capitan and I quickly went wider to include it.

On the way to dinner with the group I breathed a sigh of relief knowing that my life had just become much easier. For many in the group, what we’d just photographed was their primary workshop objective—for some Horsetail Fall is a bucket-list item. But the nights Horsetail Fall doesn’t light up are far more frequent than the nights it does, and in fact I’ve seen Februarys when it’s only lit up like that once or twice (and I’m sure there have been years when it doesn’t happen at all). While I knew nobody would hold me accountable if Horsetail didn’t put on a show for us, the fact that it did (not to mention the fabulous Horsetail shoot of our first night), meant that I was free to focus the group’s final two sunsets two very special moonrises.

Next up, sunset number three: A marvelous night for a moondance

* * *

Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

Posted on February 14, 2014

If the National Weather Service website were human, it would have long ago slapped me with a restraining order. You see, California is in the throes of an unprecedented drought that has shriveled lakes, rivers, creeks, and reduced even the most robust waterfalls to a trickle. With my Yosemite Horsetail Fall (which on a good day is rarely more than a thin white stripe on El Capitan’s granite) workshop just around the corner, recent weeks have seen me behave more like an obsessed infatuee, as if constant monitoring will somehow make my weather dreams come true. But so far this winter, each time I thought Mother Nature had winked in my direction, I found my hopes quickly dashed as every promising storm made an abrupt left into the open arms of the already saturated Pacific Northwest.

So, imagine my excitement when, just in time for this week’s workshop, an atmospheric river (dubbed the “Pineapple Express” for its origins in the warm subtropical waters surrounding Hawaii) took aim at Northern California. During the four days immediately prior to my workshop, our mountains were drenched with up to ten inches of liquid—not nearly enough to quench our three-year-and-counting drought, but more than enough to recharge Yosemite’s parched waterfalls for the three-and-a-half days of the workshop. Phew.

Monday morning I arrived in Yosemite to find, as hoped, the waterfalls brimming and Horsetail Fall looking particularly healthy. Eying Horsetail from the El Capitan picnic area a few hours before the workshop started, I suddenly remembered the stress that comes with other photographers counting on me for the bucket-list shot they’d traveled so far to capture. It occurred to me that hen Horsetail Fall is dry I can concentrate without distraction on Yosemite’s other great sunset options; when Horsetail is flowing, I need to decide whether to go for the notoriously fickle sunset light and risk no photographable sunset at all if it doesn’t happen. That’s because, not only does Horsetail Fall need water, the red glow everyone covets also requires direct sunlight at the exact instant of sunset—never a sure thing, even on seemingly clear days. And if Horsetail doesn’t get sunset light, there’s little else to photograph from its prime vantage points. With the forecast for the workshop’s duration called for a disconcerting mix of clouds and blue sky, our odds were even longer than ordinary. Compounding my anxiety was the full moon that I’d promised for workshop sunsets three and four (of four total sunsets)—if we don’t get Horsetail on sunset one or two, I’d have to decide between going for Horsetail or the moon. (And woe betide the workshop leader whose group watches a fiery sky or ascending moon from an unsuitable location—tar and feathers, anyone?)

During the orientation I did my best to establish reasonable expectations. I told the group that we’ll go all-in on Horsetail for sunsets one and two, and that if it doesn’t happen, I’ll decide our priority for sunsets three and four based on the conditions. What I meant was, we’ll go all-in for Horsetail on sunsets one and two, and I’ll hope like crazy it that does happen and I won’t have to decide anything for sunsets three and four. What followed was four sunsets filled with anxiety, each culminating with a rousing success—two our our successes were of the exactly-what-I’d-hoped-for variety, while the other two were far beyond what I could have imagined.

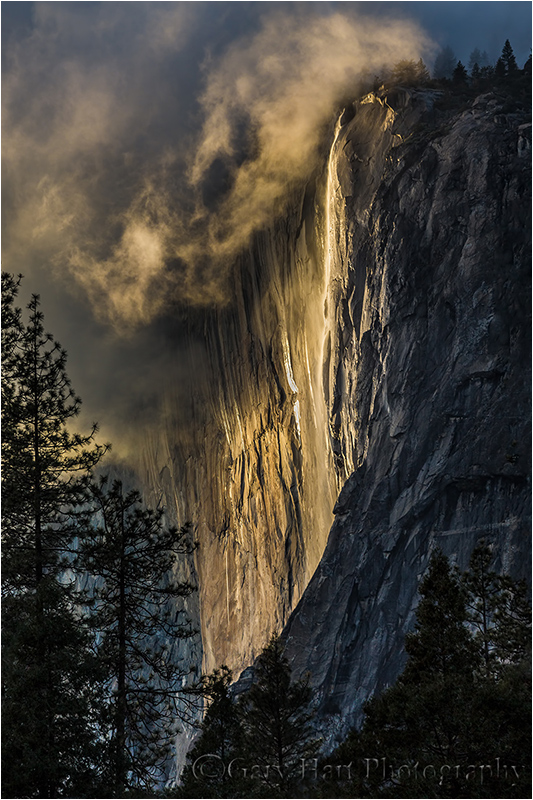

Sunset number one, above, was in the more than I could have imagined category. After the orientation I took the group to Tunnel View, where we kicked off the workshop with Yosemite Valley beneath a nice mix of clouds and sky. From there we headed to the night’s sunset destination, my favorite Horsetail Fall view on Southside Drive. A few years ago I could pull in to this spot a few minutes before sunset and be relatively confident of finding enough room for my entire group. But this spot is no longer a secret; on the drive there I crossed my fingers that the storm had kept most of the day-trip photographers home—if not, Plan B was to loop over to the El Capitan picnic area where there’s more parking and ample room for many photographers. On this afternoon my concerns were unwarranted as we found only two other cars there, and nobody down by the river where I like to set up. And set up we did, with a little more than an hour to wait. From the time we arrived the clouds were nice, but with no sign of the sun the scene was a little flat, with gray the predominant color—nevertheless, I encouraged everyone to be ready because it can change in a heartbeat. Little did I know….

As we waited we watched Horsetail Fall, spilling more water than I’d seen in years, play peek-a-boo with the storm’s swirling vestiges. But without direct sunlight, the scene, while pretty, wasn’t spectacular. Then, shortly before 5:00, without warning the clouds lit up like they’d been plugged in and I (unnecessarily) told everyone to start shooting, that we have no idea how long this light will last. For the next ten minutes we were treated to a Horsetail Fall show the likes of which I’ve never seen. Suddenly the exposures, quite easy in the flat gray, became quite tricky and I spent lots of time bouncing between workshop participants struggling with exposure. I managed to get off a handful of frames, some fairly wide, and a few a little tighter like this one. When the light faded we were left with cards devoid the “classic” Horsetail image; instead, we had something both beautiful and unique, a difficult combination for such a heavily photographed phenomenon. From the conversations in the car, and from images shared later during image review, it was pretty clear that everyone else was as happy as I was. Nevertheless, I sensed most still wanted the red Horsetail image, and I was ready to give it one more try with sunset number two.

Next up, sunset number two: The “classic” Horsetail.

* * *