Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Looking back, looking forward

Posted on December 29, 2014

For the final shoot of my final 2014 workshop, I guided my group up the rain-slick granite behind Yosemite’s Tunnel View for a slightly different perspective than they’d seen earlier in the workshop. I warned everyone that slippery rock and the steepness of the slope could make the footing treacherous (and offered a safer alternative), but promised the view would be worth it. Then I crossed my fingers.

While sunset at Tunnel View is often special, the rare sunset event I’d been pointing to for over a year, a nearly full (96%) moon rising into the twilight hues above Half Dome, is a particular highlight, one of my favorite things in the world to witness. But after an autumn dominated by clear skies that would have been perfect for our moonrise, a much needed storm landed just as our workshop started, engulfing Yosemite Valley in dense clouds, recharging the waterfalls, and painting the surrounding peaks white. Rain clouds make great photography, but they’re not so great for viewing the moon.

As you can see from this image, the clouds this evening cooperated, glazing the valley floor, but parting above Half Dome enough to reveal the moon. The moon was already high above Half Dome when it peeked out, and shortly thereafter the retreating storm’s vestiges were fringed with sunset pink. As I often do at these moments, I encouraged everyone to forget their cameras for a minute and just appreciate that they may be viewing the most beautiful thing happening on Earth at this moment. Together we enjoyed what was a once-in-a-lifetime moment for them, and a fitting conclusion to another wonderful year of photography for me.

Like any other photographer who makes an effort to get out in difficult, unpredictable conditions, I had many of these “most beautiful thing on Earth” moments in 2014—they’re what keep me going. The last couple of weeks I’ve been browsing my 2014 captures and re-appreciating my blessings. Among other things, in 2014 I rafted the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, was humbled by the Milky Way’s glow above the Kilauea Caldera, shivered beneath starlit bristlecone pines, and was electrified by the Grand Canyon monsoon’s pyrotechnics.

Most of my trips start with a plan, and while a lot of my 2o14 experiences followed the script, many deviated from my expectations, often in wonderful ways. My original vision of the moonrise on this December evening was clear skies that would allow the moon to shine; an alternate vision was a sky-obscuring storm that provided photogenic clouds. We ended up with the best of both, a hybrid of clouds and sky that I dared not hope for.

While I have a general plan in place for 2015, some places I’ll be returning to, others I’ll photograph for the first time, I know from experience that my plans won’t always go as planned. Clouds will hide the moon and stars, clear skies will cast harsh light, rivers will flood, waterfalls will wither, rivers will flood. But I also know that many of those thwarted plans will lead to unexpected rewards like this.

Here’s to a great 2015!

2014 in Review

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh your screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, full moon, Half Dome, Moon, Photography, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Building a scene

Posted on December 21, 2014

Clearing Storm Reflection, El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall, Valley View, Yosemite

Sony a7R

16 mm

.8 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

Lots of variables go into creating a successful landscape image. Many people struggle with the scene variables—light, depth, and motion—that are managed by your camera’s exposure settings: shutter speed, f-stop, ISO. Others struggle more with the composition variables: identifying, isolating, and framing a subject. (I’m not denying that there’s overlap between the exposure and composition sides of image creation, but leveraging that overlap requires independent mastery of both sides.)

Getting the exposure variables out of the way

Because I want to write more about the composition decisions that went into this image, I’ll only touch briefly on my exposure choices for the above image. I approach every scene with at my camera’s best ISO (100) and lens’s “ideal” f-stop (generally f11, where lenses tend to be sharpest, the depth of field is good, and diffraction is minimal).

Given that motion wasn’t a factor (I was on a tripod, the wind was calm, and the river’s motion didn’t concern me), I stuck with ISO 100. And even though the submerged rocks provided lots of visual interest in the immediate foreground, my 16mm focal length provided more than enough depth of field at f11—focusing about four feet into the scene would give me sharpness from around two feet to infinity. That was easy.

With those two variables established, I spot-metered on the brightest part of the scene and set dialed my shutter speed until the exposure was as bright as felt I could get away with without hopelessly blowing the highlights. This ensured that my scene (shadows included) was as bright as I could safely make it.

Here’s what I was thinking

Reflections of El Capitan, Cathedral Rocks, and Bridalveil Fall make Valley View one of the most photographed locations in Yosemite Valley. I usually I try to find something a little different than the standard view here, but the cloudy vestiges of a passing storm reflecting in the Merced River provide an irresistible opportunity to take advantage of everything that makes Valley View so special.

Some scenes you can walk up to and plant your tripod pretty much anywhere without much difference in your background subjects (though that’s rarely the case with foreground/background relationships). That’s not the case at Valley View, where the difficulty starts with distracting, non-photogenic shrubs on the near riverbank—to keep them out of the frame, you need to hop the rocks all the way down to the river.

The bigger problem at Valley View is getting all the primary elements into the image—too far to the left, and El Capitan disappears behind a stand of evergreens; too far to the right and another stand of evergreens occludes most or all of Bridalveil Fall. I moved into the fifteen-foot section of riverbank that gives me what I consider an adequate view of both, and started studying the submerged and protruding rocks right in front of me, looking for a workable foreground.

I’ll often move around quite a bit to control foreground/background subject relationships; in this case I found little benefit from shifting and stayed more or less in the same place. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t vary my shots—I tried a variety of compositions, but wide and tight, horizontal (above) and vertical (below). Some used lots of sky, while others (like this one) minimized the sky to emphasize the foreground. Still others were of the reflection only, or of the reflections with just a thin stripe of the opposite riverbank. The other variable I played with was my polarizer, which I turned to maximize and minimize the reflection, plus a combination (like both images here).

As with many images, composition at the top of the page required some compromises. I liked the way the vertical version leads the eye through the scene, and frames it with the two most striking elements—El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall. But I also wanted a horizontal rendering that would open up the scene and express its broad grandeur.

An often forgotten component of successful photography is what gets left out—an image’s perimeter are frequently home to distractions overlooked by photographers too drawn to their primary subjects. So the problem making a Valley View horizontal composition that’s wide enough to include the reflection and river rocks, is the introduction of potentially distracting elements on the far left and right.

In this case my greatest problem was the scene’s left side, with its bare trees, brown riverbank, and exposed rocks, it was rife with potential distractions to deal with. Shifting the entire composition to the right would have thrown the frame off balance, and added a lot of real estate that wasn’t worthy of the scene. Going tighter would have sacrificed too much river rock and reflection, an essential feature in my mind. I could have removed my shoes and socks, rolled up my pants, and walked forward through the (frigid) water—that move would have solved all my problems, but probably wouldn’t have been appreciated by all the other nearby photographers.

I ended up using the trees and rocks to frame the left side of the image, taking care to allow the entire arc of the riverbank to complete so it didn’t look like the nearby rocks (on the left) belonged a different scene. The vertical version doesn’t have these problems, and though it sacrifices the breadth of the horizontal composition, hold a gun to my head and I might tell you it’s the vertical version I prefer. (But it’s nice to have a choice.)

A Valley View Gallery

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, How-to, Valley View, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, composition, El Capitan, nature photography, Photography, Valley View, Yosemite

Revisiting Photography’s 3 P’s

Posted on December 15, 2014

Parting the Clouds, Yosemite Valley Moonrise, Tunnel View

Sony a7R

72 mm

1/15 second

F/11

ISO 100

Let’s review

I often speak and write about “The 3 P’s of nature photography,” sacrifices a nature photographer must make to consistently create successful images.

- Preparation is your foundation, the research you do that gets you in the right place at the right time, and the vision and mastery of your camera that allows you to wring the most from the moment.

- Persistence is patience with a dash of stubbornness. It’s what keeps you going back when the first, second, or hundredth attempt has been thwarted by unexpected light, weather, or a host of other frustrations, and keeps you out there long after any sane person would have given up.

- Pain is the willingness to suffer for your craft. I’m not suggesting that you risk your life for the sake of a coveted capture, but you do need to be able to ignore the tug of a warm fire, full stomach, sound sleep, and dry clothes, because the unfortunate truth is that the best photographs almost always seem to happen when most of the world would rather be inside.

Picking an image and trying to assign one or more of the 3 P’s to it is a fun little exercise I sometimes use to remind myself to keep doing the extra work. Take a few minutes to scan your favorite captures; ask yourself how many didn’t require at least one of the 3 P’s. (I’ll wait.) …….. See what I mean?

So which of my 3 P’s do I credit for this one? Well, there was the Persistence to continue going out in the rain all week, with no guarantee we’d see anything beyond 100 yards (because in Yosemite, if you stay inside until the rain stops, you’re too late). And of course photographing in the rain is nothing if not a Pain. But more than anything else, this one was about…

Preparation

(If you discount the unavoidable knowledge gained by a lifetime of Yosemite visits and and decades of plain old picture clicking) the preparation for this image started when I plotted the 2014 December moon and determined that it would rise at sunset, nearly full, above Half Dome in the month’s first week. So of course I scheduled a workshop for that week.

But there was more to the preparation than just figuring out where the moon would be. Of course as the workshop approached, I monitored the weather forecast and arrived in Yosemite prepared for rain. (Duh.) And throughout the workshop I monitored the weather obsessively, scouring each National Weather Service forecast update (every six hours), monitoring radar, not to mention the good old fashioned walk-outside-and-look-up technique.

Before going out for our penultimate afternoon shoot, I determined exactly what time the moon would appear above Half Dome, though I had little hope that the clouds would part enough to reveal it. Nevertheless, I wanted to to keep the group within striking distance of Tunnel View, just in case. When the latest weather forecast indicated a possible break in the rain late that afternoon, I started watching the sky closely—a clearing storm plus the moon would be pretty cool for everyone (including this life-long Yosemite photographer). The instant the clouds showed a hint of brightening (a subtle precursor to an imminent break that every photographer should be able to read), I raced everyone back up to Tunnel View.

As we pulled into the Tunnel View lot, not only was the storm starting to clear, a small patch of the first blue sky we’d seen in two days was widening above Half Dome. I held my breath and crossed my fingers for the blue to expand just a little more, because I knew exactly where the moon was and it was oh so close.

We didn’t need to wait long—within five minutes a thin piece of moon poked through, then a little more, and soon there it was, floating in that small blue patch between Half Dome and Sentinel Dome. It hung in there for less than five minutes before the clouds regrouped and swallowed the sky.

Epilogue

With more rain in the forecast, driving down from Tunnel View that night I felt certain that this unexpected, brief convergence of moon and sky was a one-time gift, that the planned moonrise for our final sunset would surely be lost to the clouds. And given what we’d just seen, I was okay with that. But Nature had a different idea….

A Gallery of Extreme Weather Rewards

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Bridalveil Fall, full moon, Half Dome, Moon, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, full moon, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Dialing it in

Posted on December 10, 2014

I’m a big fan of the polarizer, so much so that each of my lenses wears a polarizer that never comes off in daylight. A couple of years ago “Outdoor Photographer” magazine published my article on using a polarizer, a slightly modified version of a blog post that appears in the Photo Tips section of this blog.

If you read that article, or pay much attention to what I write here, you know that while a polarizer can really crank up the blue in your sky, I’m not generally a fan of what the polarizer does to the sky. I find blue sky boring—making it more blue just distracts from my primary subject. And worse still, because polarization varies with the angle of view (maximum polarization occurs when composing perpendicular to the sunlight’s direction, minimum when you’re parallel to the sunlight), wide shots (in particular) display “differential polarization” that manifests as unnatural sky-color variation across the frame.

Where I find a polarizer most indispensable is terrestrial reflections. With a simple twist of a polarizer, a mirror reflection on still water is magically erased to reveal submerged rocks and leaves. More than the reflections we see on still water, a properly oriented polarizer removes distracting, color-robbing glare that jumps off of rocks and foliage. And you don’t need direct sunlight to enjoy a polarizer’s benefits—because reflections and glare exist in overcast and full shade conditions, a polarizer can significantly enhance those images as well.

But back to this differential polarization thing. As most know, a polarizer isn’t a filter that you simply slap on a lens and forget about. A rotates in its frame, changing the amount of polarization on the way—if you’re not orienting (rotating) your polarizer with each composition, you’re better off keeping it in your bag. Watching through your viewfinder as you rotate, you’ll see the scene darken and brighten—maximum polarization occurs when the scene is darkest. These changes may appear subtle at first, and in some cases will be barely visible, but the more you train your eye, the easier it becomes to detect even the most subtle polarization.

Since polarization varies with the angle of view, and any image encompasses a broad angle of view, the amount of polarization you see in any given image varies. While differential polarization is a real pain in images with a uniform surface (like a blue sky), understanding that a polarizer isn’t an all or nothing tool allows you to dial the reflection up in some parts of the scene, and down in others. Rather than automatically dialing the polarizer until the scene darkens (maximum polarization), or until the reflection pops out (minimum polarization), turn the polarizer slowly and watch the reflection advance and retreat as you turn.

That’s exactly what I did with the above image from last week’s Yosemite trip. The sunlit vestiges of a day-long rain swirled above Valley View and reflected in the drought-starved Merced River (one storm does not a drought break). Here I opted for a wide, vertical composition that left room for both foreground and sky tightly framed by El Capitan on the left and Cathedral Rocks and Bridalveil Fall on the right.

Faced with a crisp reflection and a submerged jigsaw of river-worn granite, I refused to choose one or the other. Instead, I composed my scene with a group of exposed rocks to anchor my immediate foreground, then carefully dialed away enough reflection to reveal the rounded rocks, while saving the portion of the reflection that duplicated the Yosemite icons.

I use Singh-Ray filters (polarizers and graduated neutral density)

A selective polarization gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, How-to, Merced River, polarizer, reflection, Valley View, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, nature photography, Photography, polarizer, reflection, Yosemite

Classic Yosemite

Posted on December 3, 2014

December 3, 2014: A brief post to share my workshop group’s good fortune this morning

I’m in Yosemite this week for my Winter Moon photo workshop. Scheduling a December workshop in Yosemite is one of those high risk/reward propositions—I know full well we could get some serious weather that could make things quite uncomfortable for photography, but winter (okay, so technically it won’t be winter for another two-a-half weeks, but it’s December for heaven’s sake, so don’t quibble) is also the best time to get the kind of conditions that make Yosemite special. In the days leading up to the workshop I’d warned everyone about the impending weather, but I’d also promised them that they were in store for something special at some point during their visit. Then I crossed my fingers….

We started Monday afternoon to blue skies and dry waterfalls, but by Tuesday morning the first major storm of California’s (usually) wet season rolled in and everything changed (literally overnight). A warm system of tropical origin, what this storm lacked in snow, it more than made up for in rain, copious rain. Starting before sunrise, we got a little shooting in before the serious stuff started, but the rest of the day was wet, wet, wet. When weather settles in like this, the ceiling drops and Yosemite’s granite features disappear behind a dense, gray curtain. Nevertheless, we found some nice photography and everyone finished the day saturated but satisfied.

This morning (Wednesday) I got the group up to Tunnel View for sunrise, where were met with more of the same—opaque clouds and lots of rain, but little else. Since Tunnel View is usually the best place to wait out a Yosemite storm (thanks to the panoramic view, and the fact that the weather almost aways clears on Yosemite Valley’s west side first), I told everyone we’d just sit tight and see what happens. A few huddled in the cars, but most of the group donned our head-to-toe rain gear and stood out in the rain, waiting (hoping) for the show to begin.

As if on cue, at just about the advertised sunrise time (there was no actual sunrise to witness), the sky brightened and the curtain parted: El Capitan was first on stage, followed closely by a rejuvenated Bridalveil Fall, and soon thereafter the star of the show, Half Dome, appeared center-stage. Radiating from the valley floor, a thick fog rolled across the scene like a viscous liquid, changing the view by the minute—for nearly an hour everyone got to experience a classic Yosemite clearing storm.

As many times as I’ve witnessed a clearing storm from Tunnel View, the experience never fails to thrill me. Overlaying one of the most beautiful scenes on Earth, infinite combinations of cloud, sky, color, and light make each one unique. And as if that’s not enough, sometimes fresh snow, a rainbow, or rising moon are added to the mix. On this morning the clearing was only temporary, with no direct light or hint of blue sky, and the rain soon returned. Not that this was a problem—with more weather in store, this morning just turned out to be the opening act.

Check out my schedule of upcoming photo workshops

A Tunnel View Clearing Storm Gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, Photography Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, clearing storm, El Capitan, Half Dome, nature photography, Photography, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Letting motion work for you

Posted on December 1, 2014

Of the many differences between our world and our camera’s world, few are more significant than motion. Image stabilization or (better yet) a tripod will reduce or eliminate or photographer-induced motion, but we often make compromises to stop motion in our scene, sacrificing depth of field or introducing noise to shorten the shutter speed enough to freeze the scene.

But what’s wrong with letting the motion work for you? While it’s impossible to duplicate the human experience of motion in a static photo, a camera’s ability to record every instant throughout the duration of capture creates an illusion of motion that can also be quite beautiful. Whether it’s stars streaked into parallel arcs by Earth’s rotation, a tumbling cascade blurred to silky white, or a vortex of spinning autumn leaves, your ability to convey the world’s motion with your images is limited only by your imagination and ability to manage your camera’s exposure variables.

I came across the this little scene in the morning shade beneath Bridalveil Fall in Yosemite. A thin trickle of water entering at the top of the pool, and exiting just out of the frame behind me, was enough to impart an imperceptible clockwise vortex. To my eye, the motion here appeared to be random drift, but I guessed a long exposure might show otherwise.

To ensure sharpness from the closest rock all the way back to the cascade, I was already at f22; by dropping my ISO to 100, dialing my polarizer to minimize reflections (thus darkening the scene by two additional stops), in the already low light I achieved a 30-second exposure. The result was an image that recorded the path of each leaf for the duration of my exposure, revealing that what looked like random drift, was indeed organized rotation.

Visualizing the way your camera will record motion requires practice—the more you do it, the better you’ll become at seeing as your camera sees. Sometimes you’ll want just the barest hint of movement; other times, lots of movement is best. I usually bracket exposures to cover a broad range of motion—not only does this give me a variety of images to choose from, each click improves my ability to anticipate the effect the next time.

A gallery of motion

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bridalveil Creek, fall color, Yosemite Tagged: autumn, Bridalveil Creek, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Seeing in the dark

Posted on November 21, 2014

One of the great joys of the digital photography is the ease with which our cameras reveal the world after dark. Scenes that are merely shadow and shape to the human eye are recorded with unseen color and detail by a digital sensor, and stars too faint to compete with moonlight shine brightly.

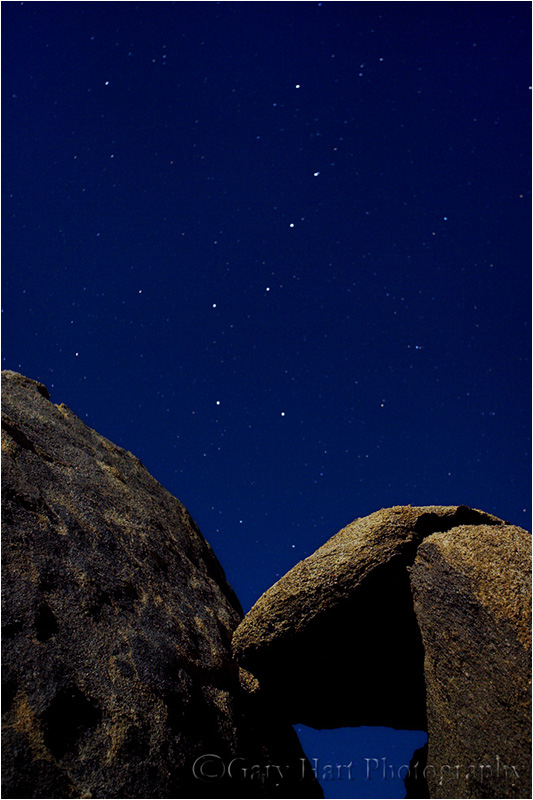

After a lifetime of refusing to sap my enjoyment of the night sky by attempting to photograph it with film, about ten years ago (a year or two into my personal digital photography renaissance) I decided to take my camera out after dark in the Alabama Hills to photograph Mt. Whitney and the sawtooth Sierra crest. It took just a few frames to realize that this was a new paradigm, but I wasn’t quite hooked until I viewed my images later that night and found, among a host of similarly forgettable Mt. Whitney among snow-capped peak images, one image of the Big Dipper framed by stacked, moonlit boulders that stood out. Ever since I’ve chased opportunities to photograph my favorite scenes after dark—first solely by the light of the full moon, and more recently (as digital sensors improve) by starlight.

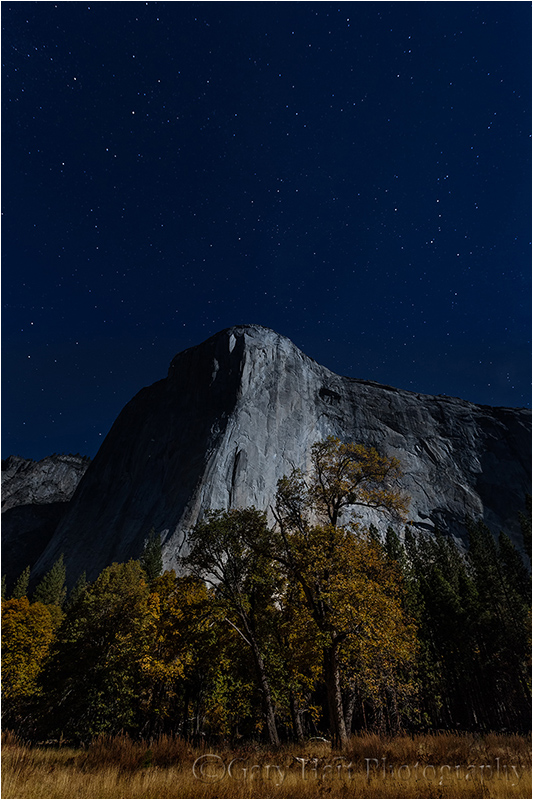

As I incorporate night photography into most of my workshops, I have no qualms about guaranteeing success for all my moonlight shoots (barring equipment failure). This month’s Yosemite Autumn Moon workshop was no exception—after photographing a beautiful full moon rising above Half Dome at sunset, we broke for dinner, then returned to the wide open spaces of El Capitan Meadow beneath El Capitan for a moonlight shoot. One of my favorite things about these moonlight shoots is the way everyone is equal parts surprised and delighted by how simple it is, not to mention how beautiful their images are.

I’d spent time that afternoon getting the group up to speed on moonlight photography (it doesn’t take long), so after a brief refresher on the exposure settings and focus technique, everyone seemed to be managing just fine without me. Feeling just slightly unessential, I decided to try a few frames of my own. Struck immediately with how beautifully the autumn gold stood out, I shifted my position to align the most prominent tree with El Capitan. As with most of my night images, I went vertical to maximize the amount of sky in my frame. I also took care to compose wide enough to include Cassiopeia on the right side of the scene.

If you have a digital SLR and a relatively sturdy tripod, you have everything you need for night photography. I have a couple of articles in my Photo Tips section to guide you: It’s best to start with moonlight photography before attempting the much more challenging starlight photography.

A moonlight gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: El Capitan, fall color, Moonlight, Photography, stars, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, moonlight, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Moon whisperer

Posted on November 14, 2014

Just when you start getting cocky, nature has a way of putting you back in your place. Case in point: last week’s full moon, which my workshop group photographed to great satisfaction from the side of Turtleback Dome, near the road just above the Wawona Tunnel.

I love photographing the moon, in all of its phases for sure, but especially in its full and crescent phases, when it hangs on the horizon in nature’s best light. I’ve developed a method that allows me to pretty much nail the time and location of the moon’s appearance from any location, and love sharing the moment with my workshop students. (Because my workflow has been in place for about ten years, I don’t use any of the excellent new software tools that automate the moon plotting process.)

Last week’s workshop was no exception, and after much plotting and re-plotting, I decided that rather than my usual Tunnel View vantage point, the view just west of the Wawona Tunnel would work better for this November’s full moon. Arriving about 30 minutes before “showtime,” I gathered everyone around and pointed a spot on Half Dome’s right side, about a third of the way above the tree-lined ridge, and told them the moon would appear right there between 4:45 and 4:50.

Sure enough, right at 4:47 there it was and I exhaled. We photographed the moon’s rise for about 30 minutes, until difference between the darkening valley and daylight-bright moon became too great for our cameras to capture lunar detail. Everyone was thrilled, and I was an instant genius—I believe I even heard “moon whisperer” on a few lips.

The workshop wrapped up the next evening, and I was still basking in my new-found moon whisperer status as I drove home down the Merced River Canyon with my daughter Ashley in the passenger seat. In a car behind us was workshop participant Laurie, who had never been down that road and wanted to follow me to the freeway in Merced.

Hungry, we stopped at one of my favorite spots, Yosemite Bug Rustic Mountain Resort in Midpines (check it out), for dinner. About an hour later, our stomachs full, we were walking back to the cars when someone pointed to a glow atop the mountain ridge above the resort. Ashley and I recognized it as the rising moon, but since this wasn’t a full disk, immediately entered into a friendly debate as to whether the moon was just peeking above the ridge, or had already risen and was disappearing behind a cloud.

We actually got quite scientific, escalating the passion with each point/counterpoint to make our cases (lest you think this was an unfair contest, I should add that Ashley’s a lawyer). Laurie remained silent. I’m not really sure how long we’d been debating when Laurie finally nudged us and pointed skyward, where, in full view of the entire Western Hemisphere, glowed the landscape illuminating spotlight of the actual full moon. Moon whisperer indeed.

(We never did figure out what the glow was.)

A full moon gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, Humor, Moon Tagged: El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Yosemite Valley: Worth getting up for

Posted on November 11, 2014

Autumn Glow, Cook’s Meadow, Yosemite

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

35 mm

.4 seconds

F/20

ISO 100

Yosemite isn’t an inherently great sunrise location. Because most of the views in Yosemite Valley face east, not only are you looking up from the bottom of a bowl, you’re composing toward the brightest part of the sky, at the shady side of your primary subjects (Half Dome, El Capitan, Yosemite and Bridalveil Falls). This is one reason I time my workshops to include one more sunset than sunrise. But I’ve come to appreciate Yosemite Valley mornings for its opportunities to create unique images that don’t resemble the beautiful but oft duplicated afternoon and sunset pictured captured when the iconic subjects are awash with warm, late light.

Over the years I’ve accumulated a number of favorite, go-to morning spots for Yosemite. I love the first light on El Capitan, which starts at the top about 15 minutes after the “official” (flat horizon) sunrise and gradually slides down the vertical granite, is a particular treat when reflected in the shaded Merced River. Other morning favorites include pre-sunrise silhouettes from Tunnel View (especially when I can include a rising crescent moon), the deep shade of Bridalveil Creek beneath Bridalveil Fall, and winter light on Yosemite Falls.

And then there’s Cook’s Meadow. Each spring you can photograph the fresh green of the meadow’s sentinel elm, Yosemite Falls booming with peak flow, and Half Dome reflected in still, vernal pools. In winter the tree is bare, exposing the twisting outline of its robust branches. The highlight each autumn is the few days when the tree is bathed in gold. On the chilliest fall mornings, sparkling hoarfrost often decorates the mounded meadow grass, and if you’re really lucky, when the air is most still, you’ll find the meadow hugged by an ephemeral mist that rises, falls, disappears, and reappears before your eyes.

On last week’s workshop’s opening morning, after a nice sunrise silhouette shoot at Tunnel View, I rushed my workshop group to Cook’s Meadow in time for the first light there. We hit the autumn big three: a hoarfrost blanket, the elm’s autumn gold still going strong, and even a few wisps of mist. The image here I captured toward the end of our shoot, just as the sun kissed the valley floor. My wide, horizontal composition emphasized the foreground, which was far more interesting than the bland (and contrail scarred) sky. I dialed in a small aperture to enhance the sunstar effect, and used a Singh-Ray 2-stop hard-transition neutral density filter to moderate the bright sky.

Within minutes the light was flat and the mist was gone, but the group was happy. Not a bad start to what turned out to be a great week of photography.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Yosemite Morning gallery

Click an image for a closer view, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Cook's Meadow, fall color, Yosemite Tagged: Cook's Meadow, nature photography, Photography, sunstar, Yosemite

If at first you don’t succeed…

Posted on November 7, 2014

Floating Leaves, Merced River, Yosemite

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

105 mm

.6 seconds

F/11

ISO 800

In early November of 2007 I took a picture that didn’t quite work out. That’s not so unusual, but somehow this one stuck with me, and I’ve spent seven years trying to recreate the moment I missed that night.

On that evening seven years ago, the sun was down and the scene I’d been working for nearly an hour, autumn leaves clinging to a log in the Merced River, was receding into the gathering gloom. The river darkened more rapidly than the leaves, and soon, with my polarizer turned to remove reflections from the river, the leaves appeared to be suspended in a black void.

I’d decided my scene lacked a visual anchor, a place for the eye to land, so I waited (and waited) for a leaf to drift into the top of my framed. On my LCD the result looked perfect, and I felt rewarded for my persistence. But back home on my large monitor, I could see that everything in the frame was sharp except my anchor point. If only I’d have bumped my ISO instead of my shutter speed….

Intrigued by the unrealized potential, I returned to this spot each autumn, but the stars never aligned—too much water (motion); dead (brown) leaves; no leaves; too many leaves; no anchor point—until this week. Not only did I find the drought-starved Merced utterly still, “my” log was perfectly adorned with a colorful leaf assortment anchored by an interlocked pair of heart-shaped cottonwood leaves.

I worked the scene until the darkness forced too much compromise with my exposure settings. In the meantime, I filled my card with horizontal and vertical, wide and tight, versions of the scene with the log both straight and diagonal. I also played with the polarizer, sometimes dialing up the reflection of overhanging trees. But I ultimately decided on the one you see her, which is pretty close to my original vision.

I can’t begin to express how happy photographing these quiet scenes makes me. I’ve done this long enough to know that it’s the dramatic landscapes and colorful sunsets that garner the most print sales and Facebook “Likes,” but nothing gives me more personal satisfaction than capturing these intimate interpretations of nature.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Autumn Intimates

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: fall color, Merced River, Yosemite Tagged: autumn, fall color, nature photography, Photography, polarizer, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About