Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Happy Earth Day

Posted on April 26, 2024

My commitment for this blog is one image/post per week. With a workshop that started Sunday and ended Wednesday, I’m a little behind this week, but I made it! Next week I have a workshop that goes from Monday through Thursday, and the following week I’ll be completely off the grid rafting the Grand Canyon. But one way or the other, I’ll continue with my once per week commitment, even if I’m a little late. And if I do have to skip a week, I’ll catch up eventually, I promise. I return you now to your regular programming…

Happy Earth Day to you

How did you celebrate Earth Day (April 22) this year? I was fortunate enough to celebrate up close and personal, guiding a workshop group around Yosemite. It’s easy to appreciate a planet when you’re surrounded by some of its most exquisite beauty, and with a group of people who appreciates it as much as you do, but every time I visit, I’m reminded that we may in fact be loving our wonders to death.

It’s impossible to have zero impact on the natural world. Every day, even if we never leave the house, we consume energy that, directly or indirectly, pollutes the atmosphere and contributes the greenhouse gases that warm our planet. The problem only worsens when we venture outdoors. Our vehicles belch exhaust, or consume electricity that was the product of invasive mining. At our destination, the clothing we wear introduces microscopic, non-indiginous flora and fauna, while the noise we create clashes with the natural sounds that comfort others and communicate information to animals. Even foot travel, the oldest, most fundamental mode of transportation, crushes rocks, plants, and small creatures with each footfall. And let’s not forget the artificial light that dilutes our once black night sky.

I’m not suggesting that we all hole up beneath a rock. If everyone just considered how their actions impact the environment and acted responsibly, our planet would be a better, more sustainable place.

Let’s get specific

The damage that’s an unavoidable consequence of keeping the natural world accessible to all is a tightrope our National Park Service does an excellent job navigating. With their EVs, organic, and recycling mindset, it’s even easy for individuals to believe that the problem is everyone else.

I mean, who’d have thought merely walking on “dirt” could impact the ecosystem for tens or hundreds of years? But before straying off the trail for that unique perspective of Delicate Arch, check out this admonition from Arches National Park. And Hawaii’s black sand beaches may appear unique and enduring, but the next time you consider scooping a sample to share with friends back on the mainland, know that Hawaii’s black sand is a finite, ephemeral phenomenon that will be replaced with “conventional” white sand as soon as its volcanic source is tapped–as evidenced by the direct correlation between the islands with the most black sands beaches and the islands with the most recent volcanic activity.

Sadly, it’s Earth’s most beautiful locations that suffer most. Yosemite’s beauty is no secret—to keep it beautiful, the National Park Service has been forced to implement a reservation system to keep the crowds (marginally) manageable. Similar crowd curtailment restrictions are in place, or being strongly considered, at other national parks. And while the reservations have helped in Yosemite and elsewhere, the shear volume of visitors who make it through guarantees too much traffic, garbage, noise, and too many boots on the ground.

While Yosemite’s durable granite may lull visitors into environmental complacency, it is now permanently scarred by decades of irresponsible climbing. And Yosemite’s fragile meadows and wetlands, home many plants and insects that are an integral part of the natural balance that makes Yosemite unique, suffer from each footstep to the point than some are now off-limits.

A few years ago, so many people crowded the elevated bank of the Merced River to photograph Horsetail Fall’s sunset show, the riverbank collapsed—that area is now off limits during Horsetail season. Despite all this, I can’t tell you how often I see people in Yosemite cavalierly trampling meadows to get in position for a shot, as a trail shortcut, or to stalk a frightened animal.

Don’t be this person

Despite the damage inflicted by the sheer volume of garden variety tourists, my biggest concern is the much smaller cohort doing a disproportionate amount of damage: photographers. Chasing the very subjects they put at risk, photographers have a vested interest and should know better. But as the urge to top the one another grows, more photographers seem to be abusing nature in ways that at best betrays their ignorance of the damage they’re doing, and at worst reveals their startling indifference to the fragility of the very subjects that inspire them to click their shutters in the first place.

If I can’t appeal to your environmental conscience, consider that simply wandering about with a camera and/or tripod labels you, “Photographer.” In that role you represent the entire photography community: when you do harm as Photographer, most observers (the general public and outdoor decision makers) simply apply the Photographer label and lump all of us, even the responsible majority, into the same offending group.

Like it or not, one photographer’s indiscretion affects the way every photographer is perceived, and potentially brings about restrictions that directly or indirectly impact all of us. So if you like fences, permits, and rules, just keep going wherever you want to go, whenever you want to go there.

It’s not that difficult

Environmental responsibility doesn’t require joining Greenpeace or dropping off the grid (not that there’s anything wrong with that). Simply taking a few minutes to understand natural concerns specific to whatever area you visit is a good place to start. Most public lands have websites with information they’d love you to read before visiting. And most park officials are more than happy to share literature on the topic (you might in fact find useful information right there in that stack of papers you jammed into your car’s center console as you drove away from the entrance station).

Most national parks have non-profit advocacy organizations that do much more than advocate, maintaining trails and underwriting park improvements that would otherwise be impossible. For example, the Yosemite Conservancy funded Bridalveil Fall’s recently completed (significant) upgrade that included new flush toilets (yay!), new trails and vistas, and enhanced handicapped access.

If you spend a lot of time at a national park, consider supporting its non-profit partner. The two I belong to are Yosemite Conservancy and Grand Canyon Conservancy.

Develop a “leave no trace” mindset

Whether or not you contribute with your wallet, you can still act responsibly in the field. Stay on established trails whenever possible, and always think before advancing by training yourself to anticipate each future step with the understanding of its impact. Believe it or not, this isn’t a particularly difficult habit to form. Whenever you see trash, please pick it up, even if it isn’t yours. And don’t be shy about gently reminding (educating) other photographers whose actions risk soiling the reputation for all of us.

A few years ago, as a condition of my national parks’ workshop permits, I was guided to The Center for Outdoor Ethics and their “Leave No Trace” initiative. There’s great information here–much of it is just plain common sense, but I guarantee you’ll learn things too.

Armed with this mindset, go forth and enjoy nature–but please save some for the rest of us.

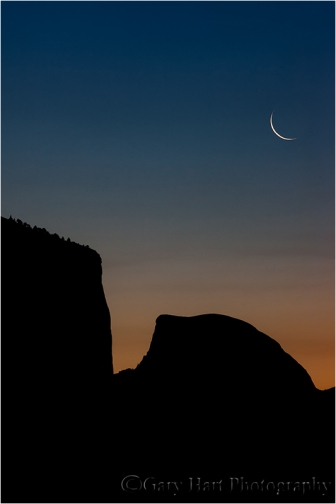

About this image

When I started taking pictures, long before the dawn of digital, my emphasis was outdoor subjects ranging from natural landscapes to urban skylines and bridges. But as my eye and overall relationship with the world has evolved, I’ve gravitated naturally toward landscapes and away from the cityscapes.

I understand now that this evolution has much to do with my love (and concern) for the natural world, both the beauty that surrounds us and damage we’re doing, and a desire to honor it. In recent years I’ve very consciously striven to, as much as possible, create images that allow people to imagine our planet untouched by humans—perhaps hoping that they’ll understand what’s at risk somehow do their share to stem the tide.

Though only number six on the current list of most visited national parks, Yosemite needs to cram the vast majority of its nearly 4-million annual visitors into the less-than 10 square miles of Yosemite Valley. In fact, for more than half the year, almost all of the park outside of Yosemite Valley is smothered in snow and closed to vehicles. This creates congestion and other problems that are unique to Yosemite.

One of the most beloved vistas on Earth, Tunnel View attracts gawkers like cats to a can-opener—all I have to say about that is, “Meow.” Despite its popularity, and the fact that the vista has indeed been crafted by the NPS (paved parking, enclosed by a low stone wall, and many trees removed to maintain the view), Tunnel View remains one of my favorite places to imagine a world without human interference.

My history with Tunnel View in Yosemite dates back to long before I ever picked up a camera, but I never take it for granted. Each time I visit, I try picture Yosemite before paintings, photographs, and word of mouth eliminated the possibility for utter surprise and awe, and what it must have been like to round a corner or crest a rise to see Yosemite Valley unfolding before you (earlier views of Yosemite were not at the current location of Tunnel View, but the overall view and experience were similar).

Today, unless I’m there for a moonrise, I rarely take out my camera at Tunnel View, preferring instead to watch the reaction of other visitors—either my workshop students or just random tourists. But every once in a while, the scene is too beautiful to resist. That happened twice for me in February, when I added two more to my (arguably already too full) Tunnel View portfolio: today’s image and the one I shared last week.

This week’s image came in the first workshop, before sunrise following an overnight rain. Though the compositions are similar, the moods of the two images are completely different. First, in last week’s image, the valley sported a thin glaze of snow, while the overnight temperatures for this week’s image weren’t quite cold enough to turn the rain to snow in Yosemite Valley (though we did find some had fallen on the east side of the valley).

But to me the biggest difference between the two images is the mood. In the snowy image I shared last week, the storm had moved on and the sky had cleared—most of the remaining clouds were local, radiating from the valley floor. The warm light of the approaching sun coloring the sky gives the scene a brighter, more uplifting feel.

The new image I share this week came during a break in the storm, but not at its end. With more rain to come, the moisture-laden sky darkened and cooled the scene, creating a brooding atmosphere. I especially like these scenes for the way they convey the timeless, prehistoric feel I seek.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Tunnel View Views

The Other AI

Posted on April 16, 2024

What’s wrong with ACTUAL intelligence (the other AI)?

I love all the genuine eclipse photos popping up on social media—almost as much as I DESPISE all the fake eclipse photos. Though we’ve had to deal with a glut of fabricated photos since the introduction of computers and digital capture to photography (all the way back before the turn of the 21st Century), the advent of artificial intelligence, combined with insatiable social media consumption, has put the bogus image problem on steroids. Despite being downright laughable, these AI frauds seem to fool a disturbing number of viewers. More concerning, many who claim they’re not fooled claim they don’t care because they still find these AI-generated fakes “beautiful.”

Acknowledging that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, all I can do is shrug and offer that my own definition of beauty is founded on truth. Not necessarily a perfect reproduction, or repetition of literal fact, but an overarching connection to some essential reality.

Whether it’s a painting, a work of fiction, a photograph, or any other artistic creation, I need to feel that essential truth connecting the scene, the artist, and me. The reality in a work of art—visual, musical, written, or whatever—doesn’t need to be, in fact usually isn’t, a literal reproduction of the world as I know it. Rather, I prefer artistic creations that reveal a previously unseen (by me) truth about the world. In other words, while paintings are rarely literal interpretations of the world (and in fact can be quite abstract), and novels by definition aren’t factual, the artistic creations I’m drawn to tap the creator’s unique take on reality to expand my own.

Even photographs, once relied on as flawless reproductions of reality, can’t possibly duplicate our 3-dimensional, unbounded, dynamic, multi-sensory reality. But they can, in the right hands, leverage the camera’s reality to expose hidden truths about the world. No matter how “stunning” an AI-generated or dishonest composite (two or more unassociated scenes in one image) image might be at first glance, they lack the artist’s perspective, or any connection to reality, sometimes both. Even worse, counterfeit images pretend to represent a reality that doesn’t exist. While it may be possible for an AI creation to require genuine human insight and creativity, so far all I see is people using AI as a shortcut around actual intelligence.

Of course photographic deception started long before digital capture, but like so many other things computers simplified, digital capture made it easy for people more interested in attention than connection to attract the strokes they covet. At least in the film days, manipulating a photo still required a bit of skill and effort—back then, when it was done honestly, you could at least admire the perpetrator’s skill.

Full disclosure (I digress)

I have to confess that I was actually party to blatant image manipulation at the age of 11, when my best friend Rob and I did a sixth grade Science Fair project on UFOs. In Rob’s backyard (and with help from Rob’s dad), we first photographed a homemade styrofoam “flying saucer” suspended on a wire against a plain tarp. Next, without advancing the film, we photographed our school, then sent the film off to be processed (who remembers those days?).

A few days later, we had a pretty convincing black-and-white print of our school beneath a hovering UFO. But, since our sole goal was to prove how easy it is to fake a UFO sighting, we did reveal the sleight-of-camera trick in our presentation (so no harm, no foul).

The digital dilemma

The introduction of computers to the world of photography, even before digital camera’s were anything more than a promising novelty, created an almost irresistible temptation for photographers who lacked the ethic or inspiration to create their own images. At the time, with no consensus on where to draw the line on digital manipulation, some photographers innocently stepped over the spot where most of us would draw it today.

For example, in the mid-90s, when Art Wolfe cloned extra zebras into his (already memorable) zebra herd image, many cried “Foul!” Wolfe, who had no intent to deceive, was taken aback by the intensity of the blowback, arguing that the resulting image was a work of art (no pun intended), not journalism.

In the long run, the discussion precipitated by Wolfe’s act probably brought more clarity to the broader digital manipulation issue by forcing photographers to consider the power and potential ramifications of the nascent technology, and to decide where they stood on the matter. Expressing his disapproval in a letter to his friend Wolfe, renowned landscape photographer Galen Rowell probably said it best: “Don’t do anything you wouldn’t feel comfortable having fully revealed in a caption.” Great advice that still applies.

Nevertheless, left up to each photographer, the “how much manipulation is too much” line remains rather fuzzy, but I think most credible photographers today agree that it excludes any form of deception. Which brings me back to the absolutely ridiculous eclipse fakes we’ve all been subjected to. I honestly don’t know what upsets me more—the fact that “photographers” are trying to pass these fakes off as real, or the number of people who they fool. (And I won’t even get into the fact that every image and word I’ve shared online has almost certainly been mined to perpetrate AI fabrication—that’s a blog for a different day.)

One risk of that mass gullibility, and people’s apathy about the distinction between real and artificial, is the dilution of photography’s perception in the public eye. As beautiful as Nature is without help, it’s pretty hard to compete with cartoonish captures when a connection to reality isn’t a criterion. I’m already seeing the effects—the volume of enthusiastic praise for obvious fakes is disturbing enough, but even more disturbing to me is the number of people responding to legitimate, creative, hard-earned images with skepticism.

So what can we do?

I’m not sure there is a complete solution to the AI problem, but I hope that enough people crying “Foul!,” on social media and elsewhere, will open eyes and force discussions that might help the public draw a line—just as the zebra debate did three decades ago. If the blowback is strong enough, perhaps even the potential stigma will be enough to discourage AI purveyors and consumers alike.

As much as I appreciate people calling out AI perpetrators in the comments of obviously fake social media posts—I’ll do this occasionally myself when I think I can contribute actual insight that might help some understand why an image is fake—I’m afraid these well-intended comments get so buried (by the “Stunning!” and “Breathtaking!” genuflections) that very few people actually see them. So one step I’ve started taking with every single fake image that soils my social media feeds is to permanently hide all future posts from that page/profile/poster. I’m probably fighting a losing battle, but at least this unforgiving, one-strike-and-you’re-out policy gives me a little satisfaction each time I do it.

About this image

One thing a still photo can do better than any other visual medium, better even than human vision, is freeze a moment in time. From explosive lightning, to crashing surf, to a crimson sunset, to swirling clouds, Nature’s most beautiful moments are also often its most ephemeral. No matter how much we believe at the time that we’ll never forget one of these special events, sadly, the memory does fade with time. But a camera and capable photographer, in addition to revealing hidden aspects of the natural world, records the actual photons illuminating those transient moments so they can be revisited and shared in perpetuity.

Which was the very last thing on my mind as this year’s February workshop group and I pulled into the Tunnel View parking lot in the predawn gloaming of this chilly morning. Instead, we were abuzz with excitement about the unexpected overnight snow that had glazed every tree and rock in Yosemite Valley with a thin veneer of white.

Our excitement compounded when we saw the scene unfolding in Yosemite Valley below. One of my most frequent Yosemite workshop questions is some version of, “Will we get some of that low fog in the valley when we’re at Tunnel View?” My standard answer is, “That’s only in the Deluxe Workshop,” but they rarely accept that. The real answer is, while this valley fog does happen from time-to-time, it’s impossible to predict the rare combination of temperature, atmospheric moisture, and still air it requires. (It’s much easier to predict the mornings when it absolutely won’t happen, which is most of them.)

But here it was, almost as if I’d ordered it up special for my group. (I tried to take credit but don’t think they were buying it.) Since I’ve seen this fog disappear as suddenly as it appears, or rise up from the valley floor to engulf the entire view in just a matter of seconds, as soon as we were parked I told the group to grab their gear and hustle to the vista as fast as they can. Then I did something I rarely do at Tunnel View anymore: I grabbed my gear and hustled to the vista as fast as I could.

While Tunnel View is one of the most beautiful views I’ve ever photographed, I’ve been here so many times that I usually don’t get my gear out here anymore—not because I no longer find it beautiful, but because it’s a rare visit that I get to see something I’ve not seen before. But since the view this morning, while not unprecedented, was truly special, I just couldn’t help myself. Another factor in my decision to photograph was that here we can all line up together, allowing me to check on and assist anyone who needs help, and still swing by my camera to click an occasional frame. This morning everyone seemed to be doing fine, so I was actually able to capture a couple of dozen frames as the fog danced below.

There were a lot of oohs and ahhs when a finger of fog rose from the valley floor and pirouetted toward Half Dome. There were many ways to photograph it, but I chose to frame it as tightly as possible, ending up with a series of a half-dozen of this particular fog feature before it morphed into something completely different. I included minimal sky because the sky above El Capitan, Half Dome, and Cathedral Rocks was relatively (compared to the rest of the scene) empty and uninteresting.

With the fog continuously shifting, to avoid cutting off any of the zigzag beneath Bridalveil Fall, I had to be extremely conscious of its spread. Depth of field wasn’t a concern because everything in my frame was at infinity. The most challenging aspect was exposure of the bright sky with the fully shaded valley. To get it all, I underexposed the foreground enough to spare the warmth of the approaching sun. The result was a virtually black foreground and colorless sky on my camera’s LCD, but I took special care to monitor my histogram and ensure that I’d be able to recover the shadows in Lightroom/Photoshop.

So, as you can see from my description, I did indeed leverage digital “manipulation” to create the finished product I share here. But my processing steps were designed to brighten the nearly black foreground my camera captured, because exposing it brighter would have resulted in a completely white sky. Since neither a white sky or a black foreground were anything close to our experience this morning, I applied actual intelligence to expose the scene and create an image that more closely reflects this actual (and unrepeatable) event in Nature.

My group rose in the frigid dark and stood bundled against the icy cold to witness this scene and capture permanent, shareable memories of our glorious morning. I imagine it might have be possible for us to have stayed in our cozy hotel rooms, open our computers, and input a few prompts in an AI image generator to come up with something similar (and why not throw in a rainbow, lightning bolts, and rising moon while we’re at it?). But where’s the joy in that?

Ephemeral Nature

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Ripping Off the Band-Aid

Posted on April 3, 2024

Frosted, Cathedral Rocks from El Capitan Bridge, Yosemite

Sony a7R V

Sony 24-105 f/4 G

ISO 100

f/13

1/10 second

We were in the midst of a beautiful Yosemite Tunnel View clearing storm when I told my group it was time to pull up stakes and move on. Some thought they’d misheard, others thought I was joking. Since we’d only started the previous afternoon, I hadn’t even really had a chance to gain the group’s trust. When one or two in the group hesitated, I assured everyone it’s like ripping off a Band-Aid, that it will only hurt for a minute and they’ll soon be glad they did it.

Many factors go into creating a good landscape image. Of course the actual in the field part is essential—things like photogenic conditions, a strong composition, and finding the ideal camera settings for exposure, focus, and depth of field. You could also cite processing that gets the most of the captured photons without taking them over the top. But an under-appreciated part of creating a good landscape image is the decision making that happens before the camera even comes out.

Some of this decision making is a simple matter of applying location knowledge. Other factors include the ability to read the weather and light, and doing the research to anticipate celestial and atmospheric phenomena (such as the sun, moon, stars, aurora, rainbows, and lightning). All of these decisions are intended to get to the right place at the right time.

A photo workshop group relies on me to do this heavy lifting in advance, and while I can’t guarantee the conditions we’ll find in a workshop scheduled at least a year in advance, my decisions should at least maximize their odds. These decisions don’t end when the workshop is scheduled—in fact, they’re much more visible (and subject to second guessing) after the workshop starts. Case in point: This morning in February.

Though the overnight forecast had promised a few rain showers followed by clearing that would last all day (yuck), before we’d even made the turn in the dark toward our Tunnel View sunrise, it was apparent the forecast had been wrong. Snow glazed all the trees, patches of fog swirled overhead, and I knew my plan to start at Tunnel View would give me the illusion of genius. At this point, my morning seemed easy.

For the next hour or so it was easy and my “genius” status remained intact as my group was treated to the Holy Grail of Yosemite photography: a continuously changing Tunnel View clearing storm, made even better by fresh snow. And if easy were my prime objective, I’d have just kept them there to blissfully bask in the morning’s beauty.

But the secret to photographing Yosemite in the snow is to keep moving, because when the conditions are beautiful in one spot, they’re just as beautiful at others. Since Yosemite’s snow, especially the relatively light dusting we enjoyed this morning, doesn’t last long once the sun hits the valley floor, our window for images of snowy Yosemite Valley was closing fast. I took comfort in the knowledge that it was virtually impossible that everyone in my group didn’t already have something truly spectacular. But, grumpy as they might have been about leaving (no one really showed it on the outside), I also knew I’d be doing them a disservice not giving them the opportunity for more great Yosemite images elsewhere in the park.

So I made the call: we’re leaving. Our next stop was El Capitan Bridge. The obvious view here is El Capitan and its reflection, visible from the bridge, but best just upstream along the south bank (actually, this bank is more east here, but since the Merced River, despite its many twists and turns, overall runs east/west through Yosemite Valley, that’s the way I’ll refer to it), but before everyone scattered I made sure they all knew about the Cathedral Rocks view and reflection from the downstream side of the bridge. Good thing.

As lovely as El Capitan was this morning, it was the downstream view that stole the show. By departing Tunnel View when we did, we were in place on the bridge when the sun broke through the diminishing clouds and poured into the valley, illuminating the recently glazed trees as if they’d been plugged in. I’d hoped that we’d make it here in time for this light, but I’d be lying if I said I expected it to be this spectacular. I hadn’t been shooting when the light hit, but when I saw what was happening I alerted everyone and rushed to capture the display before the sunlight reached the river and washed out the reflection. Some were already shooting it, but soon the rest of the group had positioned themselves somewhere along the rail to capture their own version.

Assessing the scene, I called out to no one in particular (everyone) that we shouldn’t just settle for the spot where we’d initially set up because the relationships between all the scene’s many elements—Cathedral Rocks, snow-covered trees, reflection, floating logs, etc.—was entirely a function of where they stood. With the entire bridge to ourselves, we all had ample space to move around and create our own shot.

I was especially drawn to the moss-covered tree tilting over the river on the bridge’s north (west) side. With a few quick stops on the way, I decided to go all-in on this striking tree and ended up on the far right end of the bridge. Being this far down meant losing some of the snowy trees and their reflection, but I decided I had enough of that great stuff and really liked the tree’s outline and color, not to mention the way this position emphasized the sideways “V” created by the tree and its reflection.

In general, I love the shear face of Cathedral Rocks from El Capitan Bridge (it’s a very popular Yosemite subject, especially among photographers looking for something that’s clearly Yosemite without resorting to its frequently photographed icons), but featuring the granite in this image would mean including blank sky that I felt would be a distraction. And I was also concerned that the sunlit rock just above the top of this frame would be too bright. So I composed as tightly as I could, eliminating the sky and sunlit rock, getting just enough of Cathedral Rocks to create a background for the illuminated evergreens. I was pleased that composing this way still allowed me to get more of the granite in my reflection.

At f/13 with my fairly wide focal length, getting front-to-back sharpness wasn’t a big problem, so I just focused on the featured tree. The greater concern was exposure. Sunlit snow is ridiculously bright, which meant that with much of my scene still in full shade, the dynamic range was off the charts. So I took great care not to blow-out the brightest trees, which of course resulted in the rest of my image looking extremely dark. But a quick check of my histogram told me I’d captured enough shadow info that brightening it later in Lightroom/Photoshop would be difficult.

By the time we were done here, I’m pretty sure everyone’s skepticism of my early exit had vanished, and that the brief sting from ripping off the Tunnel View band-aid was more than assuaged by the images we got after we left. By late morning, the snow was gone.

Yosemite in the Snow

Category: Cathedral Rocks, reflection, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7R V, Yosemite Tagged: Cathedral Rocks, nature photography, reflection, snow, Yosemite

Tunnel Vision

Posted on April 24, 2023

For everyone who woke up today thinking, “Gee, I sure wish there were more Yosemite pictures from Tunnel View,” you’ve come to the right place. Okay, seriously, the world probably doesn’t actually need any more Tunnel View pictures, but that’s not going to stop me.

Visitors who burst from the darkness of the Wawona Tunnel like Dorothy stepping from her monochrome farmhouse into the color of Oz, are greeted by a veritable who’s who of Yosemite icons: El Capitan, Cloud’s Rest, Half Dome, Sentinel Rock, Sentinel Dome, Cathedral Rocks, Bridalveil Fall, and Leaning Tower.

Yosemite Tunnel View subjects

Camera or not, that’s a lot to take in. First-time visitors might just just snap a picture of the whole thing and call it good. For more seasoned visitors like me, the challenge at Tunnel View is creating unique (or at least less common) images. But that’s not enough to keep me from returning, over and over.

Many people’s mental image of Yosemite was formed by the numerous Ansel Adams prints of this view. And while it’s quite possible those images were indeed captured at Tunnel View, many Adams prints assumed to be Tunnel View were actually captured from nearby Inspiration Point, 1,000 feet higher.

Before Wawona Tunnel’s opening in 1933 completed the current Wawona Road into Yosemite Valley, the vista we now know as Tunnel View was just an anonymous granite slope on the side of a mountain. Before 1933, visitors entering Yosemite from the south navigated Old Wawona Road, a steep, winding track more suited to horses and wagons than motorized vehicles. Inspiration Point was the Tunnel View equivalent on this old road.

To complicate matters further, there are actually three Inspiration Points in Yosemite. The original Inspiration Point is the location where the first non-Native eyes feasted on Yosemite Valley in the mid-19th century. Decades later, Old Wawona Road was carved into the forest and granite to provide an “easier” (relatively speaking) route between Wawona and Yosemite Valley. The valley vista that was established on this route and labeled Inspiration Point is the one popularized by Ansel Adams. But today that version of Inspiration Point has become so overgrown that hikers hardy enough to complete the steep climb up to the Ansel Adams Inspiration Point, must make their way a short distance down the slope to a spot where the view opens up, forming the New Inspiration Point. But I digress…

Almost certainly not my first visit

My total visits to Tunnel View, which predate my oldest memories, by now have to exceed 1,000. At first I had no say in the matter, having simply been a passenger on family trips since infancy. But when I became old enough to drive myself, my Tunnel View visits increased—most Yosemite trips included multiple visits.

The Tunnel View counter started clicking even faster as my interest in photography grew. More than just a one-of-a-kind scene to photograph, Tunnel View is also the best place in Yosemite to survey Yosemite Valley for a read on the current conditions elsewhere in the valley.

And as I’ve mentioned (ad nauseam), the view at Tunnel View is beautiful by any standard. And as it turns out, beauty is a pretty essential quality for a landscape image. Unfortunately, another essential landscape image criterion, especially for landscape photographers who pay the bills with their photography, is a unique image—ideally (aspirationally), but not necessarily, a one-of-a-kind image. So Tunnel View’s combination of unparalleled beauty and easy access means million of visitors each year, which makes finding something literally unique (one-of-a-kind) here virtually impossible.

But there are a few things I do to increase my chances of capturing something special enough to at least stand out—things you can do at any popular photo spot. Here are three:

- Experiment with focal length — At Tunnel View usually means using a telephoto to isolate individual elements, or combinations of elements: just El Capitan, or El Capitan and Half Dome; just Half Dome, or Half Dome and Bridalveil Fall; and so on. And an extreme telephoto allows me to zero in on just one aspect of a Tunnel View icon: Half Dome’s summit draped by clouds, El Capitan’s bold diagonals, the mist explosion at Bridalveil’s base, to name just three.

- Look behind you — Even though the granite walls outside Tunnel View’s classic view can’t compete with the money shot, failure to keep an eye on the surrounding walls risks missing light and clouds that can at times be spectacular. And even though I don’t photograph manmade objects, I’ve seen some great images by others using Wawona Tunnel to frame Yosemite Valley, or with the tunnel itself as the subject.

- Include special conditions — My favorite Tunnel View approach is to pair this already beautiful scene with one of the many ephemeral natural events possible here. Not only does the east-facing view mean warm late light on all the granite features, it also makes Tunnel View ideally situated for rising crescent (sunrise) and full (sunset) moons, and afternoon rainbows. And its position on Yosemite Valley’s west end means it’s usually the first place in Yosemite Valley that storms clear. Few sights in Nature more spectacular than a Tunnel View clearing storm, and no two are exactly the same.

The image I’m sharing today combines a couple of these approaches: a tighter than typical focal length, and special conditions. Though the Bridalveil Fall rainbow isn’t exactly unique, its combination of beauty and relative rarity keeps me coming back. And because the sun’s angle at any given moment, as well as the angle of view to Bridalveil Fall, are precisely known, I can predict the rainbow’s appearance each spring afternoon to within a few minutes (it varies slightly with the amount of water in the fall).

This rainbow makes a fantastic first shoot for my spring workshops. Usually I’m content to just stand and watch—and listen to the exclamations from my workshop students—but sometimes it’s to beautiful to resist. This year, with beautiful clouds overhead, dappled sunlight below, and a strong breeze to spread the rainbow’s palette, was one of those times.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A Tunnel View Gallery

The Third Time’s the Charm

Posted on December 12, 2022

Large or small, crescent or full, I love photographing the moon rising above Yosemite. I truly believe it’s one of the most beautiful sights on Earth. The moon’s alignment with Yosemite Valley changes from month-to-month, with my favorite full moon alignment coming in the short-day months near the winter solstice when it rises between El Capitan and Half Dome (from Tunnel View), but I have a plan for each season. Some years the position and timing are better than others, but when everything clicks, I do my best to be there. And if I’m going to be there anyway, why not schedule a workshop? (He asked rhetorically.)

Strike one, strike two

For last week’s Yosemite Winter Moon photo workshop, I’d planned three moonrises, from three increasingly distant vantage points. On our first night, despite the cloudy vestiges of a departing storm, I got the group in position for a moonrise at a favorite Merced River sunset spot, hoping the promised clearing would arrive before the moon. The main feature here is Half Dome, but the clouds had other ideas. Though they eventually relented just enough to reveal Half Dome’s ethereal outline and prevent the shoot from being a complete loss, the moon never appeared. Strike one.

With a better forecast for the second evening, we headed into the park that afternoon with high hopes. But as the sun dropped, the clouds thickened to the point where not only did I fear we’d miss the moon again, I was pretty sure Half Dome would be a no-show as well. So I completely aborted the moonrise shoot and opted for sunset at Valley View, where El Capitan and freshly recharged Bridalveil Fall were on their best behavior. The result was a spectacular sunset that made me look like a genius (phew), but still no moon. Strike two.

Revisiting nature photography’s 3 P’s

Because the right mindset is such an important part of successful photography, many years ago I identified three essential qualities that I call the 3 P’s of Nature Photography:

- Preparation is (among many things) your foundation; it’s the research you do that gets you in the right place at the right time, the mastery of your camera and exposure variables that allow you to wring the most from the moment, and the creative vision, refined by years of experience, and conscious out-side-the-box thinking.

- Persistence is patience with a dash of stubbornness. It’s what keeps you going back when the first, second, or hundredth attempt has been thwarted by unexpected light, weather, or a host of other frustrations, and keeps you out there long after any sane person would have given up.

- Pain is the willingness to suffer for your craft. I’m not suggesting that you risk your life for the sake of a coveted capture, but you do need to be able to ignore the tug of a warm fire, full stomach, sound sleep, and dry clothes, because the unfortunate truth is that the best photographs almost always seem to happen when most of the world would rather be inside.

Most successful images require one or more of these three essential elements. Chasing the moon last week in frigid, sometimes wet, Yosemite got me thinking about the 3 P’s again, and how their application led to a (spoiler alert) success on our third and final moonrise opportunity.

Meanwhile…

As we drove into the Tunnel View parking lot, about 45 minutes before sunset, our chances for the moon looked excellent. There were a few clouds overhead, with more hanging low on the eastern horizon behind Half Dome, but nothing too ominous. My preparation (there’s one) had told me that the moon this evening would appear from behind El Capitan’s diagonal shoulder, about halfway up the face, and that area of the sky was perfectly clear. So far so good.

Organizing my group along the Tunnel View wall, I pointed out where the moon would appear, and reminded them of the previously covered exposure technique for capturing a daylight-bright moon above a darkening landscape. Eventually I set up my own tripod and Sony a7R IV, with my Sony 200 – 600 G lens with the 2X Teleconverter pointed at ground 0. In my pocket was my Sony 24 – 105 G lens, which I planned to switch to as soon as the moon separated from El Capitan. Then we all just bundled up against the elements and enjoyed the view, waiting for the real show…

But, as if summoned by some sinister force determined to frustrate me, the seemingly benign clouds hailed reinforcements that expanded and thickened right before our eyes. Their first victim was Half Dome, and it looked like they’d set their sights on El Capitan next. By the time sunset rolled around, my optimism had dropped from a solid 9 to a wavering 2. I knew the moon was up somewhere behind the curtain and tried to stay positive, but let everyone know that our chances for actually seeing it were no longer very good. I reminded them not to get so locked in on waiting for the moon that they miss out on the beauty happening right now. Ever the optimist, I switched to my 24-105, privately rationalizing that even without the moon, we’d had so much spectacular non-moon photography already, nobody could be unhappy. But still…

At that point it would have been easy to cut our losses, come in out of the cold (pain), and head to dinner. But I have enough experience with Yosemite to know that it’s full of surprises, and never to go all-in on it’s next move. So we stayed. And our persistence (we’ve checked all three now) was rewarded when, seemingly out of nowhere, a hole opened in the clouds and there was the moon. The next 10 minutes were a blur of frantic clicking and excited exclamation as my group enjoyed this gift we’d all just about given up on.

A few full moon photography tips

- Sun and moon rise/set times always assume a flat horizon, which means the sun usually disappears behind the local terrain before the “official” sunset, while the moon appears after moonrise. When that happens, there’s usually not enough light to capture landscape detail in the moon and landscape, always my goal. To capture the entire scene with a single click (no image blending), I usually try to photograph the rising full moon on the day before it’s full, when the nearly full (99% or so illuminated) moon rises before the landscape has darkened significantly.

- The moon’s size in an image is determined by the focal length—the longer the lens, the larger the moon appears. Photographing a large moon above a particular subject requires not only the correct alignment, it also requires distance from the subject—the farther back your position, the longer the lens you can use without cutting your landscape subject.

- To capture detail in a rising full moon and the landscape (in a single click), increase the exposure until the highlight alert appears on your LCD (any more exposure blows out the moon). At that point, you can’t increase the exposure any more, even though the landscape is darkening. You’ll be amazed by how much useable data you’ll be able to pull from the in nearly black shadows in Lightroom/Photoshop (or whatever your processing software). In the image I share above, my LCD looked nearly black except for the single white dot of moon. Eventually the scene will become too dark—exactly when that happens depends on your camera, but if you’re careful, you can keep shooting until at least 15 minutes after sunset.

Learn More

Moon Over Yosemite

Category: Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Rocks, El Capitan, full moon, Moon, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7RIV, Tunnel View, winter, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Rocks, El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, moon, moonrise, nature photography, Tunnel View, winter, Yosemite

Secure Your Borders

Posted on November 28, 2022

Autumn Leaves on the Rocks, Valley View Reflection, Yosemite

Sony a7R IV

Sony 24-105 G

1/40 second

F/16

ISO 100

It’s easy to be overwhelmed at the first sight of a location you’ve longed to visit for years. And since by the time you make it there you’ve likely seen so many others’ images of the scene, it’s understandable that your perception of how the scene should be photographed might be fixed. But is that really the best way to photograph it?

Valley View in Yosemite is one of those hyper-familiar scenes. El Capitan, Bridalveil Fall, and Cathedral Rocks pretty much slap you in the face the instant you land at Valley View, making it easy to miss all the other great stuff here. This month’s workshop group visited Valley View twice, with each visit in completely different conditions, which got me thinking about about the number of ways there are to photograph most scenes, and how it’s easy to miss opportunities if you simply concentrate on the obvious. Most scenes, familiar or not, require scrutiny to determine where the best images are—on every visit.

On our first visit, Bridalveil Fall was just a trickle lost in deep shadow, so I focused my attention on El Capitan, opting for a vertical frame to emphasize El Cap, the beautiful clouds overhead, and the reflection. When we returned a couple of days later, Bridalveil had been recharged by a recent rain, the soft light was more even throughout the scene, and patches of fallen leaves and pine needles now floated atop the reflection. All this called for a completely different approach.

On this return visit, since I thought there was (just barely) enough water in Bridalveil to justify its inclusion, I went with a horizontal composition. It would have been easy to frame up El Capitan, Bridalveil, and Cathedral Rocks, throw in a little reflection and call it good. But (as my workshop students will confirm) I obsess about clean borders because I think they’re the easiest place for distractions to hide.

So before every click, I do a little “border patrol,” a simple reminder to deal with small distractions on my frame’s perimeter that can have a disproportionately large impact on the entire image. (I’d love to say that I coined the term in this context, but I think I got it from fellow photographer and friend Brenda Tharp—not sure where Brenda picked it up.)

To understand the importance of securing your borders, it’s important to understand that our goal as photographers is to create an image that not only invites viewers to enter, but also persuades them to stay. And the surest way to keep viewers in your image is to help them forget the world outside the frame. Lots of factors go into crafting an inviting, persuasive image—things like compositional balance, visual motion, and relationships are all essential (and topics for another day), but nothing reminds a viewer of the world outside the frame more than an object jutting in or cut off at the edge.

When an object juts in on the edge of a frame, it often feels like part of a different scene is photobombing the image. Likewise, when an object is cut off on the edge of the frame, it can feel like part of the scene is missing. Either way, it’s a subconscious and often jarring reminder of the world beyond the frame. Not only does this “rule” apply to obvious terrestrial objects like rocks and branches, it applies equally to clouds.

And there are other potential problems on the edge of an image. Simply having something with lots of visual weight—an object with enough bulk, brightness, contrast, or anything else that pulls the eye—on the edge of the frame can throw off the balance and compete with the primary subject for the viewer’s attention.

Of course it’s often (usually?) impossible to avoid cutting something off on the edge of the frame, so the next best thing is to cut it boldly rather than to simply trim it. I find that when I do this, it feels intentional and less like a mistake that I simply missed. And often, these strongly cut border objects serve as framing elements that hold the eye in the frame.

To avoid these distractions, I remind myself of “border patrol” and slowly run my eyes around the perimeter of the frame. Sometimes border patrol is easy—a simple scene with just a small handful of objects to organize, all conveniently grouped toward the center, usually requires minimal border management. But more often than not we’re dealing with complex scenes containing multiple objects scattered throughout and beyond the frame. Even when you can’t avoid cutting things off, border patrol makes those choices conscious instead of random, which is almost aways better.

As nice as the Valley View reflection was on this visit, it was sharing space with a disorganized mess of rocks, driftwood, and leaves. Organizing it all into something coherent was impossible, but I at least wanted to have prominent color in my foreground and take care to avoid objects on the edge of my frame that would pull viewers’ eyes away from the scene.

Unfortunately, as I used to tell my kids all the time (they’re grown and no longer listen to me), you can’t always have what you want. In this case, including the best foreground color also meant including an unsightly jumble of wood, rock, and pine needles in the lower right corner. But after trying a lot of different things, I decided this was the best solution—especially since I managed to find a position and focal length that gave me completely clean borders everywhere else in my frame.

I very consciously included enough of the mass in the lower right that it became something of a boundary for that corner of the image (not great, but the best solution possible). I also was very careful to keep an eye on the ever-changing clouds. The light on El Capitan that broke through just as I had my composition worked out felt like a small gift.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Valley View Variety

Shooting the Light Fantastic

Posted on December 5, 2021

Blue sky may be great for picnics and outdoor weddings, but it makes for lousy photography. To avoid boring blue skies, flat midday light, and extreme highlight/shadow contrast, landscape photographers usually go for the color of sunrise and sunset, and low-angle sunlight of early morning and late afternoon.

Of course the great light equalizer is clouds, which can soften harsh light and add enough texture and character to the sky, making almost any subject photographable—any time of day. Sadly, clouds are never guaranteed, especially here in California. Fortunately, all is not lost when the great clouds and light we hope for don’t manifest.

Spending a large part of my photography time in Yosemite, over the years I’ve created a mental list for when to find the “best” cloudless-sky light on Yosemite’s icons: for Half Dome, Bridalveil Fall, and Cathedral Rocks it’s late afternoon through sunset; El Capitan is good early morning, while Yosemite Falls is best a little later in the morning. And then there are seasonal considerations: Half Dome at the end of the day is good year-round, but Bridalveil Fall and Cathedral Rocks are much better from April through September; while El Capitan gets nice morning light year-round, it also gets good late light from October through February; and while the best light on Yosemite Falls happens in winter, that doesn’t usually coincide with the best water, which comes in spring (unless you’re lucky enough to get a lot of early rain, like we got this autumn).

But even when the sun’s up and the sky is blank, all is not lost. In those situations I head to locations I can photograph in full shade. Yosemite Valley’s steep walls help a lot, especially from November through February, when much of the valley never gets direct sun.

Following our sunrise shoot on the first morning of last month’s Yosemite Fall Color photo workshop, I took my group to El Capitan Bridge to photograph the first light on El Capitan. But as nice as that El Capitan first light was, on this morning I couldn’t help notice the downstream view of Cathedral Rocks across the bridge. With everything on that side in full shade, this downstream scene wasn’t as dramatic as the sun-warmed El Capitan, but the soft, shadowless light was ideal for the colorful trees reflecting in the Merced River.

After encouraging everyone in the group not to check out this downstream view, I went to work on the scene. If the sky had been more interesting, I’d have opted for my Sony 16-35 GM lens to include all of Cathedral Rocks, more trees, lots of reflection, and an ample slice of sky. But the sky this morning was both bright and blue (yuck), so I chose the Sony 24-105G lens for my Sony a7RIV to tighten the composition.

Before shooting, I actually walked up and down at the railing quite a bit, framing up both horizontal and vertical sample compositions, until I found the right balance of granite, trees, and reflection. Because the air was perfectly still, I didn’t need to worry about movement in the leaves, which enabled me to add my Breakthrough 6-stop Dark Circular Polarizer for a shutter speed long enough the smooth some of the ripples in the water.

I guess the lesson here is the importance of understanding and leveraging light. And all this talk about light inspired me to dust off my Light Photo Tips article—I’ve added the updated and clarified version below (with a gallery of images beneath it).

Light

Three Strikes, Lightning and Rainbow from Bright Angel Point, Grand Canyon

Good light, bad light

Photograph: “Photo” comes from phos, the Greek word for light; “graph” is from graphos, the Greek word for write. And that’s pretty much what photographers do: Write with light.

Because we have no control over the sun, nature photographers spend a lot of time hoping for “good” light and cursing “bad” light—despite the fact that there is no universal definition of “good” and “bad” light. Before embracing someone else’s good/bad light labels, let me offer that I (and most other serious photographers) could probably show you images that defy any good/bad label you’ve heard. The best definition of good light is light that allows us to do what we want to do; bad light is light that prevents us from doing what we want to do.

Studio photographers’ complete control of the light that illuminates their subjects, a true art, allows them to define and create their own “good” light. On the other hand, nature photographers, rely on sunlight and don’t have that kind of control. But knowledge is power: The better we understand light—what it is, what it does, and why/how it does it—the better we can anticipate and be present for the light we seek, and deal with the light we encounter.

The qualities of light

Energy generated by the sun bathes Earth in continuous electromagnetic radiation, its wavelengths ranging from extremely short to extremely long (how’s that for specific?). Among the broad spectrum of electromagnetic solar wavelengths we receive are ultraviolet rays that burn our skin (10-400 nanometers), infrared waves that warm our atmosphere (700 nanometers to 1 millimeter), and the visible spectrum that we (and our cameras) use to view the world—a narrow range of wavelengths between ultraviolet and infrared with wavelengths that range between 400 and 700 nanometers.

When all visible wavelengths are present, we perceive the light as white (colorless). But when light interacts with an object, the object absorbs or scatters some of the light’s wavelengths. The amount of scattering and absorption is determined by the interfering object’s properties. For example, when light strikes a tree, characteristics of the tree determine which of its wavelengths are absorbed, and the wavelengths not absorbed are scattered. Our eyes capture these scattered wavelengths and send that information to our brains, which translates it into a color.

When light strikes a mountain lake, some is absorbed by the water, allowing us to see the water. Some light bounces back to the atmosphere to create a reflection. The light that isn’t absorbed or reflected by the water light passes through to the lakebed and we see whatever is on the lake’s bottom.

This vivid sunrise was reflected by the glassy surface of Mono Lake, but just enough light made it through to reveal the outline of submerged tufa fragments on the lake bed.

Let’s get specific

Rainbows

For evidence of light’s colors, look no farther than the rainbow. Because light slows when it passes through water, but shorter wavelengths slow more than longer wavelengths, water refracts (bends) light. A single beam of white light (light with an evenly distributed array of the entire visible spectrum) entering a raindrop separates and spreads into a full range of visible wavelengths that we perceive a range of colors. When this separated light strikes the back of the raindrop, some of it reflects: A rainbow!

Under the Rainbow, Colorado River, Grand Canyon

Blue sky

When sunlight reaches Earth, the relatively small nitrogen and oxygen molecules that are most prevalent in our atmosphere scatter its shorter wavelengths (violet and blue) first, turning the sky overhead (the most direct path to our eyes) blue. The longer wavelengths (orange and red) don’t scatter as easily continue traveling through more atmosphere—while our midday sky is blue, these long wavelengths are coloring the sunset sky of someone to the east.

In the mountains, sunlight has passed through even less atmosphere and the sky appears even more blue than it does at sea level. On the other hand, when relatively large pollution and dust molecules are present, all the wavelengths (colors) scatter, resulting in a murky, less colorful sky (picture what happens when your toddler mixes all the paints in her watercolor set).

Most photographers (myself included) don’t like blank blue sky. Clouds are interesting, and their absence is boring. Additionally, when the sun is overhead, bright highlights and deep shadows create contrast that cameras struggle to handle. That means even a sky completely obscured by a homogeneous gray stratus layer, while nearly as boring as blue sky, is generally preferred because it reduces contrast and softens the light (more below).

Sunrise, sunset

Remember the blue light that scattered to color our midday sky? The longer orange and red wavelengths that didn’t scatter overhead, continued on. As the Earth rotates, eventually our location reaches the point where the sun is low and the sunlight that reaches us has had to fight its way through so much atmosphere that it’s been stripped of all blueness, leaving only its longest wavelengths to paint our sunrise/sunset sky shades of orange and red.

When I evaluate a scene for vivid sunrise/sunset color potential, I look for an opening on the horizon for the sunlight to pass through, pristine air (such as the clean air immediately after a rain) that won’t muddy the color, and clouds overhead and opposite the sun, to catch the color.

Overcast and shade

Sunny days are generally no fun for nature photographers. In full sunlight, direct light mixed with dark shadows often forces nature photographers to choose between exposing for the highlights or the shadows (or to resort to multi-image blending). So when the sun is high, I generally hope for clouds or look for shade.

Clouds diffuse the omni-directional sunlight—instead of originating from a single point, overcast light is spread evenly across the sky, filling shadows and painting the entire landscape in diffuse light. Similarly, whether caused by a single tree or a towering mountain, all shadow light is indirect. While the entire scene may be darker, the range of tones in shade very easily handled by a camera.

Flat gray sky or deep shade may appear dull and boring, but it’s usually the best light for midday photography. When skies are overcast, I can photograph all day—rather than seeking sweeping landscapes, in this light I tend to look for more intimate scenes that minimize or completely exclude the sky. And when the midday sun shines bright, I look for subjects in full shade. Overcast and shade is also the best light for blurring water because it requires longer shutter speeds.

Another option for midday light is high-key photography that uses the overexposed sky as a brilliant background. Putting a backlit subject against the bright sky, I simply meter on my subject and blow out the sky.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Leveraging light

Whether I’m traveling to a photo shoot, or looking for something near home, my decisions are always based on getting myself to my locations when the conditions are best. For example, in Yosemite I generally prefer sunset because that’s when Yosemite Valley’s most photogenic features get late, warm light. Mt. Whitney, on the other side of the Sierra, gets its best light at sunrise, and I prefer photographing the lush redwood forests along the California coast in rain or fog. Though I plan obsessively to get myself in the right place, in the best light, sometimes Nature throws a curve, just to remind me (it seems) not to get so locked in on my subject and the general tendencies of its light that I fail to recognize the best light at that moment.

The Light Fantastic

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show.

Category: Cathedral Rocks, fall color, How-to, reflection, Sony 24-105 f/4 G, Sony a7RIV, Yosemite Tagged: autumn, Cathedral Rocks, fall color, Merced River, nature photography, reflection, Yosemite

You Can’t Have It Both Ways

Posted on December 13, 2020

Years of leading photo workshops and reviewing the work of others has convinced me that to capture great images and maintain domestic bliss, you need to decide before a trip whether you’ll be a photographer or tourist—it’s pretty hard to have it both ways. (I say this completely without judgement—there are times when I opt for tourist mode myself, packing only the camera in my iPhone.) I see many well-executed images taken at the wrong times—harsh shadows, blue sky, and poorly located light are all signs that the photographer was sightseeing with his or her camera. Not that there’s anything wrong with that—if your priority was simply to record the scene and you’re happy with the result, the image was a success.

But getting the pictures coveted by serious photographers usually requires being outside at the most inconvenient times. That’s sacrifice a serious photographer will make without hesitation, but the rest of the family? Not so much. Countless intimate getaways and family vacations have been ruined by the photographer who thinks it’ll be no problem tiptoeing out for sunrise (“I’ll be so quiet, you won’t even know I left”), or waiting “just a few minutes longer” after sunset for the Milky Way (“The drive-thru will still be open when we get back”).

When I’m wearing my photographer hat, my decisions put me outside when the conditions are most conducive to finding the images I want, without considering comfort or convenience. Sunrise, sunset, overcast skies, wild weather, darkness are all great for photography, but face it—few people without a camera are thrilled to be outdoors when they’re sleepy, hungry, cold, wet, or ignored.

Many of us, myself included, are blessed with wives/husbands/partners who say quite genuinely, “No problem, take as long as you want—I’ll just read (or wait in the room, or go shopping, or whatever).” And though we know they mean it, based on my own experience and reports from others, even blessed by a sincere sanction from our significant other, we’re still distracted by the knowledge that he or she is waiting, biding time, (and possibly suffering) while we pursue our solitary passion. When someone is waiting for me, I just can’t help rushing my compositions, making decisions designed to get me back fast instead of satisfied, and just generally shortcutting everything I do. Invariably, disappointment ensues.

And when the goal is a pleasant trip with family, if I try to squeeze in photography, I can’t relax and my photography suffers. That’s why, when I’m a tourist, my goal is to simply chill and and enjoy the sights with the people I love. When I leave my camera home, my lights-out and rise times are based on everyone’s comfort and enjoyment, the pace is never rushed, and my forays into nature are timed for convenience and the most pleasant weather for being outside. And guess what: I return with my body and mind fresh and my loved ones happy.

Of course doing nature photography for a living makes it easier for me separate photography and family trips. I get lots of me-time to dedicate to photography, but some people are so busy that their only opportunity to take pictures is when they’re on vacation. In this case, perhaps a compromise can be negotiated. After researching your route and destinations, pick a (reasonable) handful of must-photograph spots. Then, before the trip, get buy-ins on your photography objectives from all concerned, and be as specific as possible: “I’d like to shoot sunrise on our second morning at the Grand Canyon,” “I’d really like to do a moonrise shoot in Yosemite on Wednesday evening,” and so on. The rest of the trip? Bring no more than a point-and-shoot or your cell phone, stash your serious camera gear out of sight, and don’t let anyone catch so much as a longing glimpse in its direction for the rest of the trip. Then relax and enjoy.

About this image

On this November morning, I didn’t have to drive too far into Yosemite Valley to know that the snow falling on fall color was the stuff of my photographic dreams. My first stop was El Capitan Bridge, a don’t-miss spot for El Capitan reflections in the Merced River. As the closest easily accessible top-to-bottom view of the massive granite monolith, El Capitan Bridge was made to order for my new Sony 12-24 f/2.8 GM lens, and I couldn’t wait to try it out. But the storm that had already dropped a couple of inches of snow was still active, wrapping El Capitan in clouds.

After little success photographing El Capitan’s barely discernable outline from the upstream side of the bridge, I crossed the road and set up on the bridge facing downstream. The tops of Cathedral Rocks were smothered by clouds, but the granite base was clearly visible above the river, framed by golden oaks. In the foreground, rafts of pine needles and autumn leaves floated by so slowly that their motion was barely perceptible.

I composed the scene the scene in the viewfinder of my Sony a7RIV, starting at 12mm and slowly tightening the composition to 16mm. As I worked the scene, the snowfall intensified and I methodically increased my ISO, from 100 to 1600, in one-stop increments, with a corresponding shutter speed increase to capture a range of motion-blur in the falling flakes, from long streaks to short dashes.

This is a perfect example weather only a photographer would be crazy enough to be outside in. Not only was it cold and wet, you couldn’t even see the tops most of Yosemite’s most photographed icons. But I’ve learned that there’s no better time to photograph in Yosemite than during and just after a snowfall, a truth I verified many times this day.

Yosemite Weather

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Category: Cathedral Rocks, fall color, Merced River, reflection, snow, Sony 12-24 f/2.8 GM, Sony a7RIV Tagged: autumn, Cathedral Rocks, fall color, nature photography, reflection, snow, winter, Yosemite

Don’t Knock Opportunity

Posted on November 15, 2020

Fall Into Winter, Bridalveil Fall Reflection, Yosemite

Sony a7RIV

Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM

1/13 second

F/16

ISO 100

A lot of factors go into creating a nice image. Much of the emphasis is on composition, and the craft of metering and focusing a scene, but this week I’ve been thinking about an often overlooked (or taken for granted) component: Opportunity.

This has been on my mind because a week ago I got the rare opportunity to be in Yosemite for the convergence of my two favorite conditions for photography there: peak fall color and fresh snow. Toss in multiple clearing storms and ubiquitous reflections, I have a hard time imagining anything topping that day (okay, maybe if there’d been a full moon…).

Every photographer who has shared a beautiful image has probably had to endure some version of, “Wow, you were sure lucky that happened.” And indeed, I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve received a gift from nature—most recently, last Sunday in Yosemite. But as I think about the blessings of this day, I’m reminded of Louis Pasteur’s oft repeated observation that chance favors the prepared mind. In other words, opportunity is great, but it’s not completely random, and you have to be ready for it.

A favorite quote of Ansel Adams and the generation of photographers who succeeded him, Pasteur’s (translated) words have been repeated and paraphrased to the point that they verge on cliché. But like most clichés, Pasteur’s words achieved this status for a reason. (In this case I can substitute “opportunity” for “chance” without really changing the meaning.)

Granted, I did indeed feel extremely lucky that the weather gods decided to drop snow on Yosemite Valley, a location that doesn’t get tons of snow anyway, just as the valley’s fall color peaked. But to simplify that opportunity down to a lucky convergence that I just happened to be present for, completely discounts the fact that my being in Yosemite that particular day was no accident. I’d been monitoring the Yosemite Valley forecast all week, cleared my schedule when it looked like snow might fall, then made the nearly 4-hour drive with no guarantees.

This does not make me a genius—I wasn’t the only photographer there, far from it. And I wasn’t granted inside information, or motivated by divine intervention—I just checked the weather forecast and acted. And while it was chilly (around 30 degrees), and wet, I didn’t really endure what I’d call extreme hardship (unless you consider spending 24 hours with my brother extreme hardship). 😬

So the first part of the preparation->opportunity equation is simply the ability to recognize the potential for good photography, combined with the willingness to act (and maybe to endure a little inconvenience and discomfort). The second part of the equation is the ability to take maximize the opportunities that manifest, whether they be the product of your proactive initiative (like monitoring the forecast and getting yourself on location), or simply a fortuitous (unexpected) happenstance (right place, right time).

At the very least, taking full advantage of photographic good fortune requires the basic ability to manage exposure and focus variables to control photography’s creative triad: motion, depth, and light. (Seriously, you cannot tap a scene’s potential without these skills, I promise.) But bolstered by this foundation, the next step is a little more subtle because it’s so easy to be overwhelmed by the beauty before you, and to just start clicking because the conditions pretty much guarantee a nice image, regardless of the effort.

True story: A few years ago I was guiding a workshop group at a location with a beautiful view of El Capitan. When the beauty is off the charts like this, rather than insert myself, I often just stand back and observe. And while doing this, I watched one member of the group approach the riverbank and survey the scene—so far, so good. But… Suddenly she popped the camera off her tripod, switched it into continuous mode, pointed downstream, and pressed the shutter and slowly swept the camera in a 180 degree arc—in 5 seconds she’d probably captured at least 50 images. Stunned, it was over before I could intervene. When I regained my composure, I asked her what in the world she was doing. She just smiled and said, “It’s Yosemite, there’s bound to be something good in there.” I couldn’t argue. (This was actually a lighthearted moment that we all had fun with for the rest of the workshop.)

Which brings me to this image from last Sunday. When I pulled up to Valley View, the snow had just stopped (temporarily), glazing every exposed surface pristine white. If any scene qualified for my workshop student’s machine gun, spray and pray, approach, this was it.

The main event at Valley View is El Capitan, but my eye was drawn to the amber trees across the Merced River, their glassy reflection, and the endless assortment of yellow leaves drifting through the scene. I also liked the way Bridalveil Fall, though definitely not gushing, etched a white stripe on the granite beneath Cathedral Rocks. Rather than settle for the easy scene, I made my way about 50 feet upstream from the parking lot to a spot where El Capitan is mostly blocked by trees, but Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Rocks, the colorful trees, and the reflection, are front and center.

Framing this scene, I dropped as low as possible to emphasize the reflection and eliminate some spindly branches dangling overhead (and said a prayer of thanks for the articulating LCD on my Sony a7RIV). After one frame, I decided the bright gray clouds reflecting on the nearest water to be distracting, so with my eye on my LCD, I dialed my polarizer until the the reflection was off the immediate foreground without erasing the reflection of the scene across the river. This darkened the bland part of the river and helped the rest of the reflection stand out.

I also realized the darker foreground could use some sprucing up. While I could say that I was lucky that a pair of leaves drifted by just beneath the Cathedral Rocks reflection, their inclusion (and position) in this image was no accident. The river was dotted with fairly continuous stream of drifting leaves, so with my composition in place, I simply waited for them to drift into my scening. I took several frames with different leaves in different positions, but liked this one because this pair so nicely framed Bridalveil Fall.

The moral of this story

I think too many photographers are limited by their own mindset. Make your own opportunities and prepare to take full advantage of them when they happen. Learn the basics of exposure and focus technique (it’s not hard). You have enough access to weather forecasts, celestial (sun, moon, stars) data, and nearby beauty (no matter where you live) to anticipate a special event and plot a trip. And once you’re there, take in your surroundings (ideally, before the action starts), avoid the obvious, and challenge yourself to not settle for the first beautiful scene to grace your viewfinder. And no matter how beautiful that image looks on your LCD, ask yourself how it could be better.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Yosemite Reflections

Click an image for a closer look, and to view a slide show.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Rocks, fall color, reflection, snow, Sony 16-35 f2.8 GM, Sony a7RIV, winter, Yosemite Tagged: autumn, Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Rocks, fall color, nature photography, reflection, snow, winter, Yosemite

Love What You Shoot

Posted on February 17, 2019

Snow and Reflection, El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall, Yosemite

Sony a7RIII

Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM

1/25 second

F/11

ISO 100

Feel the love

One frequently uttered piece of photographic advice is to “shoot what you love.” And while photographing the locations and subjects we love most is indeed pretty essential to consistently successful images, unless we treat our favorite subjects with the love they deserve, we risk losing them.

My relationship with Yosemite predates my memories, so it’s no wonder that Yosemite Valley plays such a significant role in my photography. Of course my love for Yosemite doesn’t make me unique, and like all Yosemite photographers, I’ve learned to share. While it’s nice to have a location to myself (I can still usually find a few of those spots in Yosemite Valley), I’m happy to enjoy Yosemite’s prime photographic real estate with other tourists and photographers. In fact, I get vicarious pleasure watching others view the Yosemite scenes I’ve been visiting my entire life.

But…

In recent years I’ve noticed more tourists and photographers abusing nature in ways that at best betrays their ignorance, and at worst reveals their indifference to the fragility of the very subjects that inspire them to click their shutters in the first place. Of course it’s impossible to have zero impact on the natural world—starting from the time we leave home, we consume energy that pollutes the atmosphere and contributes greenhouse gases. Once we arrive at our destination, every footfall alters the world in ways ranging from subtle to dramatic—not only do our shoes crush rocks, plants, and small creatures, our noise clashes with the natural sounds that comfort humans and communicate to animals, and our vehicles and clothing scatter microscopic, non-indigenous flora and fauna.

A certain amount of damage is an unavoidable consequence of keeping the natural world accessible to all who would like to appreciate it, a tightrope our National Park Service does an excellent job navigating. It’s even easy to believe that we’re not the problem—I mean, who’d have thought merely walking on “dirt” could impact the ecosystem for tens or hundreds of years? But, for example, before straying off the trail for that unique perspective of Delicate Arch in Arches National Park, check out this admonition from the park.