Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

The yin and yang of nature photography

Posted on August 7, 2014

Clearing Storm, El Capitan and the Merced River, Yosemite

Canon 1Ds Mark III

17 mm

1/8 second

F/11

ISO 100

Conducting photo workshops gives me unique insight into what inhibits aspiring nature photographers, and what propels them. The vast majority of photographers I instruct, from beginners to professionals, approach their craft with either a strong analytical or strong intuitive bias—one side or the other is strong, but rarely both. And rather than simply getting out of the way, the underdeveloped (notice I didn’t say “weaker”) side of that mental continuum seems to be in active battle with its dominant counterpart.

On the other hand, the photographers who consistently amaze with their beautiful, creative images are those who have negotiated a balance between their conflicting mental camps. They’re able to analyze and execute the plan-and-setup stage of a shoot, control their camera, then seamlessly relinquish command to their aesthetic instincts as the time to click approaches. The product of this mental détente is a creative synergy that you see in the work of the most successful photograpers.

At the beginning of a workshop I try to identify where my photographers fall on the analytical/intuitive spectrum and nurture their undeveloped side. When I hear, “I have a good eye for composition, but…,” I know instantly that I’ll need to convince him he’s smarter than his camera (he is). Our time in the field will be spent demystifying and simplifying metering, exposure, and depth management until it’s an ally rather than a distracting source of frustration. Fortunately, while much of the available photography education is technical enough to intimidate Einstein, the foundation for mastering photography’s technical side is ridiculously simple.

Conversely, before the sentence that begins, “I know my camera inside and out, but…,” is out of her mouth, I know I’ll need to foster this photographer’s curiosity, encourage experimentation, and help her purge the rules that constrain her creativity. We’ll think in terms of whether the scene feels right, and work on what-if camera games (“What happens if I do this”) that break rules. Success won’t require a brain transplant, she’ll just need to learn to value and trust her instincts.

Technical proficiency provides the ability to control photography variables beyond mere composition: light, motion, and depth. Intuition is the key to breaking the rules that inhibit creativity. In conflict these qualities are mutual anchors; in concert they’re the yin and yang of photography.

About this image

With snow in the forecast for a December morning a few years ago, I drove to Yosemite and waited out the storm. When the snow finally stopped, I made the best of the three or so hours of daylight remaining.

Rather than return to some of the more popular photo locations, like Tunnel View or Valley View, I ended up at this spot along the Merced River. Not only his is a great place for a full view of El Capitan, it’s also just about the only place in Yosemite Valley with a clear view of the Three Brothers (just upriver and out the frame in this image). Downriver here are Cathedral Rocks and Cathedral Spires.

As I’d hoped, the snow was untouched and I had the place to myself. My decision to wrap up my day here was validated when the setting sun snuck through and painted the clouds gold.

Yosemite Winter

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, Merced River, Photography, reflection, snow, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, nature photography, snow, Yosemite

Moonbow: Nature’s little secret

Posted on May 20, 2014

Moonbow and Big Dipper, Lower Yosemite Fall, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

22 mm

30 seconds

F/4

ISO 800

Rainbows demystified

A rainbow forms when sunlight strikes airborne water droplets and is separated into its component spectral colors by characteristics of the water. The separated light is reflected back to our eyes when it strikes the backside of the droplets: Voila!—a rainbow.

Despite their seemingly random advent and location in the sky, rainbows follow very specific rules of nature—there’s nothing random about a rainbow. Draw an imaginary line from the sun, through the back of your head, and exiting between your eyes; the rainbow will form a full circle at 42 degrees surrounding that line (this won’t be on the test). Normally, because the horizon almost always gets in the way, we usually see no more than half of the rainbow’s circle (otherwise it would be called a “raincircle”). The lower the sun is, the higher the rainbow and the more of it we see; once the sun is higher than 42 degrees (assuming a flat horizon), we don’t see the rainbow at all unless we’re at a vantage point that allows us to look down (for example, at the rim of the Grand Canyon).

Read more about rainbows on my Photo Tips Rainbows Demystified page.

Moonbows

Moonlight is nothing more than reflected sunlight—like all reflections, moonlight retains a dimmer version of most of the qualities of its source (the sun). So it stands to reason that moonlight would cause a less bright rainbow under the same conditions that sunlight causes a rainbow. And guess what—it does! So why have so few people heard of moonbows? I thought you’d never ask.

Color vision isn’t nearly as important to survival in the wild as the ability to see shapes, so human vision evolved to bias shape over color in low-light conditions. In other words, colorful moonbows have been there all along, we just haven’t be able to see them. But cameras, with their ability to dial up sensitivity to light (high ISO) and accumulate light (long exposures), “see” much better in low light than you and I do.

While it’s entirely possible for a moonbow to form when moonlight strikes rain, the vast majority of moonbow photographs are waterfall-based. I suspect that’s because waterfall moonbows are so predictable—unlike a sunlight rainbow, which doesn’t require any special photo gear (a smartphone snap will do it), capturing a lunar rainbow requires at the very least enough foresight to carry a tripod, and enough knowledge to know where to look.

Nevertheless, even though we can’t see a moonbow’s color with the unaided eye, it’s not completely invisible. In fact, even without color, there’s nothing at all subtle about a bright moonbow—it may not jump out at you the way a sunlight rainbow does, but if you know where to look, you can’t miss a moonbow’s shimmering silver band arcing across the water source.

Yosemite Falls moonbow

Despite frequent claims to the contrary, moonbows can be seen on many, many waterfalls. Among the more heralded moonbow waterfalls are Victoria Falls in Africa, Cumberland Fall in Kentucky, and (of course) Yosemite Falls in Yosemite National Park.

Yosemite Falls is separated into three connected components: Upper Yosemite Fall plummets about 1400 feet from the north rim of Yosemite Valley; the middle section is a series of cascades dropping more than 600 feet to connect the upper and lower falls; Lower Yosemite Fall drops over 300 feet to the valley floor. While there are many locations from which to photograph the moonbow on Upper Yosemite Fall, the most popular spot to photograph it is from the bridge at the base of Lower Yosemite Fall.

The Lower Yosemite Fall moonbow is not a secret. Arrive at the bridge shortly after sunset on a full moon night in April, May, and (usually) June, and you’ll find yourself in an atmosphere of tailgate-party-like reverie. By all means come with your camera and tripod, but leave your photography expectations at home or risk appreciating the majesty of this natural wonder. In springs following a typical winter the mist and wind (the fall generates its own wind) on and near the bridge will drench revelers and cameras alike. After a particularly wet winter, the airborne water and long exposures can completely obscure your lens’s view during the necessarily long exposures. And if the wet conditions aren’t enough, if you can find a suitable vantage point, expect to find yourself constantly jostled by a densely packed contingent of photographers and gawkers stumbling about in limited light. Oh yeah, and then there are the frequent flashes and flashlights that will inevitably intrude upon your long exposures.

But, if you still have visions of a moonbow image, it’s best to come prepared:

- A tripod and digital SLR camera are must (a film camera will work too, but it adds complications I won’t get into here)

- Wear head-to-toe rain gear so you can concentrate on keeping your camera dry

- Bring a chamois or bath towel—you’ll be using it frequently

- An umbrella can help keep water off your lens during a long exposure

- Practice moonlight photography (you’ll find my how-to of moonlight photography, including exposure settings and focus techniques, in the link) before you get there—trust me when I say that you don’t want to be learning how to photograph by moonlight while you’re trying to capture a moonbow.

- Don’t have time to practice before your visit? Stop at the top of the Lower Yosemite Falls trail, where you can see the entire fall from top-to-bottom, and practice there—the conditions are much easier, and moonbow or not, these could turn out to be your favorite images of the night.

About this image

I’d taken my May workshop group to Glacier Point on this night, so we didn’t arrive at Yosemite Falls until nearly an hour after the moonbow started. This late arrival was intentional on my part because California’s severe drought has severely curtailed the mist at the base of the lower fall. In a normal year the mist rises so high that the moonbow starts when the moon is quite low (remember, the lower the sun or moon, the higher the bow); this year, I knew that the best moonbow wouldn’t appear until the moon rose and the bow dropped into the heaviest mist.

I’d given the group a talk on moonlight photography that afternoon, but we stopped at the top of the trail to practice for about 20 minutes, using the exquisite, tree-framed view of the entire fall. When everyone had had a success, we took the short walk up to the bridge and got to work.

We found conditions that night were remarkably manageable—by the time we arrived at the bridge, at around 9:45, some of the crowd had thinned, and our dry winter meant virtually no mist on the bridge to contend with. I started with couple of frames to get more precise exposure values to share with the group (moonlight exposures can vary by a stop or so, based on the fullness of the moon, its size that month, and atmospheric conditions), then spent most of my time was spent assisting everyone and negotiating locations for them to shoot (basically, wedging my tripod into an opening then inviting someone in the group to take my spot).

This image is one of my early test exposures—I went just wide enough to include the Big Dipper (just because it’s a test doesn’t mean I’ll ignore my composition). In wetter years I’ve captured move vivid double moonbows and complete arcs that stretch all the way across the frame, but I kind of like the simplicity of this year’s image. I’ve been including the Big Dipper in my moonbow images for many years because I just can’t resist it. I’ve found that May is the best month to capture it in a position that makes it appear to be pouring in the fall.

Join me as we do it all over again in next year’s Yosemite Moonbow and Wildflowers photo workshop or Yosemite Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop

Category: How-to, Moon, Moonbow, Moonlight, rainbow, stars, Yosemite Falls Tagged: moonbow, moonlight, Photography, Yosemite, Yosemite Fall

Another day, another moonrise

Posted on May 16, 2014

* * * * *

Previously on Eloquent Nature

* * * * *

May 13, 2014

After seeing the images captured by the people in my group followed me on Monday evening, during the next day’s image review session a few in my workshop group asked if we could go back up to Glacier Point for sunset that night. I did a quick-and-dirty plotting and showed them about where the moon would be at sunset (I usually tend to be more OCD about precision when plotting the moon, but “about” was good enough for our purposes), explaining that I’d planned to photograph the moonrise from a different spot that night, but I’d be willing to forego that shoot in favor of a Glacier Point reprise if that’s what everyone preferred. But, I warned, tonight would also be our only opportunity to photograph the Lower Yosemite Fall moonbow—if we drive up to Glacier Point, we probably won’t make it back down to the valley for the moonbow shoot until after 9:00. While that would be plenty early enough for the moonbow, it would mean we’d have been going from before 6:00 a.m. until about 11:00 p.m. But the vote was unanimous, so back up we went.

I love plotting a moonrise. I’ve been doing it for a long time—when done right there’s no mystery to the time and location of the moon’s arrival, but there’s just something thrilling about the watching the moon peek above the horizon. (Not to mention the (unjustified) awe my workshop groups express when it happens exactly when and where I’d predicted.) When we considering altering the schedule I’d them that we’d see the at around 7:40, give or take five minutes, just a little to the left of Mt. Starr King. And sure enough, at 7:36 there it was, a white wafer poking from behind the left flank of Gray Peak (the left-most peak in the above image).

Full disclosure

Before you decide that my moon prediction makes me some kind of photography savant, I should probably explain why the camera I used to photograph this scene was my backup, 1DS Mark III, and not my primary, 5D Mark III. (The 1DS III is still a great camera, it’s just seven-year old technology.) That would be because, genius that I am, my camera bag, complete with camera, lenses, tripod, and filters was still back at the hotel. Fortunately, knowing the way workshops force me out of my routine (leading to a long history of forgotten tripods and cameras abandoned by the roadside), I always have a backup tripod and camera bag with my backup camera and a lens or two in the back of my car. Which is how my 1DS III and 100-400 lens (which I find too bulky and awkward for everyday use) were back there and ready for action. What I didn’t have was my remote release and graduated neutral density filters, essential to my twilight moonrise workflow. Fortunately, one of the workshop students took pity on me and loaned me a GND she wouldn’t be using (thanks, Lynda!); I turned on the 2-second timer to eliminate shutter-press vibrations.

But anyway…

As cool as the moon’s appearance was, the best full moonrise photography doesn’t come until a little later. From about five minutes before sunset, when the sky has darkened enough for the daylight-bright moon stand out, until about ten minutes after sunrise, when the foreground has darkened too much to be captured with a single frame (even with the use of a GND), is my moonrise “prime time.”

But even though the best stuff wouldn’t come until later, I photographed the moonrise from its first appearance, varying my composition as much as the 100-400 lens would allow—getting Half Dome in the frame was out of the question, but since I’d already covered that the night before, this was going to be more of a telephoto shoot anyway. Everything was at infinity, but in this case I opted for f8 (f11 is my usual “default” f-stop) and ISO 400 because, given the weight of the 1DSIII and 100-400 lens, I was a little concerned about my tripod’s ability to dampen completely after 2-seconds. By the time the light got really good and the sky started to pink-up, I was quite familiar with all the compositions and was able to cycle through them very efficiently.

By about 8:15 we were hustling back down the mountain to our date with the moonbow. But that’s a story for a different day….

Join me as we do it all over again in next year’s Yosemite Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop

Category: full moon, Glacier Point, Moon, Yosemite Tagged: full moon, Glacier Point, moon, Mt. Starr King, Photography, Yosemite

Glacier Point moonrise

Posted on May 13, 2014

May 12, 2014

I’ve been in Yosemite for my annual Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop. Monday night I took the group to Glacier Point for sunset—an unexpected benefit of California’s drought that allowed Glacier Point Road to open weeks earlier than normal. I knew a nearly full moon would be rising above the Sierra crest that evening, but figured that since it would be so far south, we wouldn’t be able to do a lot with it. But when I arrived Glacier Point and saw the moon rising above Mt. Starr King, I realized that shifting slightly south, away from the popular Glacier Point View, might just allow us to include the moon and Half Dome in a wide shot. Hmmm. But because we had people in the group who had never been to Glacier Point, I decided now was not the time for exploration.

As always happens at Glacier Point on these predominantly clear evenings, the light on Half Dome warmed beautifully as the sun dropped to the horizon behind us. Organizing an expansive landscape into a coherent image can be difficult, especially for first timer visitors. But as I moved between the students positioned along the rail, it seemed that all were doing fine and realized that my greatest value at the moment was to stay out of the way. Appreciating the view, I just couldn’t get that moon, blocked by trees from our vantage point, out of my mind.

When a couple of people in the group asked why I wasn’t shooting (it always makes them nervous when the leader is looking at the same view they’re photographing but shows no interest in shooting), I told them I was simply enjoying the view (quite true). But when someone asked if I had any suggestions for something different, my ears perked up. I told them if I were to be shooting, I’d go back up the trail a hundred yards or so to see if I could get around the trees and find something that included the moon.

When several people sounded interested, I warned them that there’s no guarantee we’d find anything photo-worthy, and relocating so close to sunset would risk missing the show entirely. Much to my delight, a couple of people said, “Let’s do it,” and that was all I needed to hear. I told Don (Don Smith, who’s assisting this workshop—for those who haven’t been paying attention, Don assists some of my workshops, I assist some of Don’s, and we do a few workshops as equal collaborations) that I was taking a few people back up the trail and off we went.

I ended up with five (nearly half the group) at the view just below the Glacier Point geology exhibit. I chose this spot for its open view, and for the way it allowed us to frame the scene with Half Dome on the left, triangular Mt. Starr King and the moon on the right, and Nevada and Vernal Falls in the center. With a couple of trees and dark granite for the foreground, the scene couldn’t have been more ideal if I’d have assembled it myself.

I took out my 16-35 and composed this scene that pretty much seemed to frame itself. Even though I had subjects ranging from the fairly close foreground the the extremely distant background, at 21mm I knew I’d have enough depth of field at f11. I used live view to focus on the foreground tree, more than distant enough to ensure sharpness throughout my frame.

While I almost always rely on my RGB histogram to check my exposure, my general exposure technique when photographing a full moon in twilight is to forego the histogram and concentrate on the moon. As far as I’m concerned, a shot is a failure if the moon’s highlights are blown (a white disk), but since the moon is such a tiny part of the frame, it barely (if at all) registers on the histogram. What does register is the blinking highlight alert that signals overexposed highlights. When the foreground is dark, I’ll continue pushing my exposure up until the moon just starts to blink (not the entire disk, just the brightest spots). I know from experience that I can recover these blown highlights in post processing. I also know that this is the most light I can give the scene, because the moon’s brightness won’t change as the foreground darkens. (While I don’t blend images, for anyone so inclined it’s quite simple to take two frames, one exposed for the foreground and the other exposed for the moon, and combine the two in Photoshop.) In this case I spot metered on the foreground to ensure enough light to retain color and detail in the rapidly darkening shadows, then used a Singh-Ray 2-stop hard graduated neutral density filter to hold back the sky and (especially) protect against blowing the moon.

* * * *

About this scene

This is the view looking east from near Glacier Point. From left to right: Cloud’s Rest (just behind Half Dome), Half Dome, Vernal Fall (below—the white water beneath Vernal Fall is cascades on the Merced River), Nevada Fall (above), Mt. Starr King (triangle shaped peak).

Join me as we do it all over again in next year’s Yosemite Moonbow and Dogwood photo workshop

Category: full moon, Glacier Point, Half Dome, Moon, Nevada Fall, Vernal Fall, Yosemite Tagged: full moon, Glacier Point, Half Dome, moon, Nevada Fall, Photography, Vernal Fall, Yosemite

Visualize, pursue, execute, enjoy

Posted on May 5, 2014

I probably worked harder capturing this image than any other image I’ve ever photographed. Worked hard not in terms of physical exertion, but rather in patient pursuit over several years and painstaking execution in difficult conditions. Photographed late last month in Yosemite, this image is something I’ve visualized and actively sought for years. While I have no illusion that this image will be as popular as some of my more conventional images, it makes me so happy that I just have to share everything that went into its capture.

Visualize: The world in a raindrop

I can trace this image back to a spring afternoon a few years ago, when I was doing macro photography in a light rain. My subject was poppies, and peering through my viewfinder I particularly loved the clarity of the raindrops when they snapped into focus. At home on my monitor I magnified one of the images to something like 400% and saw the entire scene surrounding me was inverted in that tiny droplet. The fact of this wasn’t new to me, but actually seeing it up close planted a small seed that bloomed into an obsession I’ve been chasing ever since. I realized that getting even closer to a raindrop might allow me to enlarge its internal scene enough to make it visible without magnification. From that thought it was a short jump to the idea of finding a raindrop that contained a scene others would recognize.

Pursue: If at first you don’t succeed…

Unfortunately, the onset of my raindrop quest coincided with a drought that severely limited my access to raindrops (and if you know anything about me, you know it has to be an actual raindrop—no spray bottles for me). And then there are the daily distractions of running a business, and the fact that many of my trips to prime locations are for workshops, when the time and attention a shot like this requires precludes me from trying it.

Nevertheless, over the last several years I’ve played with my idea when opportunities presented themselves. These experiences allowed me to determine that 100mm macro wouldn’t get me close enough, that I’d need to add multiple extension tubes. And the extremely narrow depth of field that comes with focusing this close would require a very small aperture to get enough of the frame sharp.

These early attempts also enabled me to identify and practice overcoming a few physical challenges: low light, caused not only by the overcast skies, but also by the extension tubes (extension reduces the amount of light reaching the sensor); wind, almost always present in a rain; and a tissue-thin focus plane (even at a small aperture) that severely shrinks my margin for error. I knew going in that it would be difficult, but with each attempt I had to admit that this shot might be even harder than I’d decided it would be the last time I tried it. Of course that’s half the fun.

A couple of weeks ago the (always reliable) weatherman called for an all-day rain in Yosemite. Perfect. Knowing the dogwood were blooming, I freed my schedule and made the 7+ hour roundtrip to Yosemite, leaving early in the morning and returning that night. The raindrop shot wasn’t my sole objective, but it was up there on my list. Unfortunately, while I ended up having a pretty good day, my “all-day” rain stopped about an hour into my visit and I was left to pursue other opportunities.

Undeterred, when the (almost always reliable) weatherman promised more rain a couple of days later, back I went, this time meeting friends Don Smith and Mike Hall. Did I mention that I wanted rain? Well, rain it did. Hard. All day. Donning head-to-toe rain gear, I managed to stay dry, but my equipment wasn’t quite so lucky—without a third arm my umbrella wasn’t much use during the compose/meter/focus phase and the small towel I’d brought to dry things off was completely saturated by the end of our first stop (I should have known better). After that I pretty much contented myself with drying my my lens element just before shooting, trusting (hoping) that my reasonably water-resistant gear would survive—if I wanted to keep shooting, I had no other choice.

As good as the shooting was, by mid-afternoon the three of us were ready to submit to the weather and head for home. But, with my raindrop shot gnawing at the back of my mind, on the way out I suggested a quick stop at the view of Bridalveil Fall on Northside Drive. I’d stopped here on Tuesday and knew the dogwood that hadn’t been quite ready for primetime then would be just about right now. So stop we did (it didn’t take lots of arm twisting).

Execute: Cruel and unusual

While Don and Mike (why does this sound like a drive-time radio program?) went off in search of their own vision, I bee-lined to the “perfect” dogwood I’d identified on Tuesday. But getting a shot like this isn’t just a matter of going out in the rain at a beautiful location. (Full disclosure: there was a time when I believed it might just be.) And in my zealous pursuit, I’d conveniently discounted the difficulties I’d need to deal with:

- Rain (of course I knew it was raining, but I always forget what a pain it is to deal with, even if I just dealt with it fifteen minutes ago)

- My “perfect” tree was on an embankment with a 45-degree slope

- A light but persistent breeze (I never notice a light breeze until I try to do macro)

- Rain (in case you forgot)

Okay, so maybe this won’t be such a quick stop.

After taking stock of the physical difficulties, I attached all three of my extension tubes (72 mm total) to my 100 mm macro lens and scanned the flowers, branches, and leaves for a raindrop that was both large enough to hold the scene (without extreme distortion) and whose long axis (the wide side) was perpendicular to my line of view to Bridalveil Fall. No small feat.

The frustration started immediately: When I did indeed find the “perfect” drop, I realized getting to it without touching the tree (thereby rearranging all its drops) would require powers far beyond my superhero grade. And so it happened that once I navigated “inside” the tree’s canopy to my raindrop, the raindrop was long gone and I had to start over.

Okay, at least I was inside the tree—progress. I ran my eyes along the nearby branches until suddenly, there it was—another perfect (there’s that word again) raindrop dangling from a diagonal branch about 18 inches in front of me. I very carefully maneuvered in its direction, using contortions that might best be described as a hybrid of moves from the party games Twister and Limbo, moves I hadn’t broken out since my (far more limber) college days. (Picture a heist movie where the cat-burglar has to avoid a matrix of electric eye beams to get to the jewels.)

This particular raindrop was about eight inches above my head. Fortunately my new (and wonderfully tall) tripod was up to the task—I extended its legs until my lens was just an inch or two from the drop and began the painstaking process of composing and focusing. With my viewfinder higher than my eye could reach, this part would have been impossible without live-view; with live-view it was a pain but doable.

I found my basic composition fairly quickly, but my ridiculously thin focus plane shifted every time the breeze or nearby raindrop-strike jostled “my” raindrop. Focusing not on the raindrop, but the scene within the raindrop, I waited for a brief lull in the breeze and nudged my focus ring until the equilibrium point around which the drop vibrates was sharp. Then I magnified the drop and waited for the next lull to confirm sharpness. After several attempts I was reasonably confident I was ready to proceed.

Stopping down to f22 with three extension tubes forced me to bump my ISO to 1600 to reach the 1/30 second shutter speed I thought I could get away with. Even this would require timing my shutter for another lull in the breeze, but the alternatives—a larger aperture which would reduce my DOF, or higher ISO that would increase the noise—I wasn’t crazy about.

You’d think after all this I’d be ready to shoot. You’d think. But by now (in case you forgot, it’s still raining) my front lens element was festooned with raindrops. And wiping the lens dry did little good because the slightly upward angle of view oriented my lens ideally for capturing more raindrops. So I extracted the collapsed umbrella I’d proactively jammed in a jacket pocket and carefully threaded it skyward, carefully negotiating the network of overhanging branches without disturbing my raindrop, until the umbrella was in a open space wide enough to unfurl. Open umbrella in my right hand, with my left hand I was able to dry with a small, dry lens cloth I’d also had the foresight stuff in a pocket.

One of the downsides of the “perfect” raindrop is its large size, which gives it a rather inconvenient relationship with gravity. So. After all this preparation and just as I raised my remote release for my first click, my raindrop grew tired of waiting and plunged groundward. True story. Fortunately, an advantage of getting intimate with raindrops is the insight that they tend to reform in the same place. I took a deep breath—with my composition, focus, and exposure already set, I decided to wait (still contorted between branches beneath my umbrella) for the next drop to form. And sure enough, within a couple of minutes I was back in business.

I clicked a dozen or so frames, checking the focus after each, refining the composition slightly, and occasionally varying my exposure settings until I was confident that I had enough frames to give me a pretty good chance of at least one successful image. I probably would have worked on it even longer, but my muscles really were starting to cramp and I figured Don and Mike were ready to move on anyway. Back at the car a cursory run through my images on my LCD was enough to give me hope that I’d achieved my goal, but it wasn’t until I got them home on my large monitor that I was ready to proclaim success.

Enjoy: All’s well that ends well

Most of the images had very slight but nevertheless fatal focus problems—slight motion blur or barely missed focus point—all I needed was one. And this is it.

So what did I end up with? The white stripe on the left is Bridalveil Fall in full spring flow. The branch belongs to my young dogwood tree; behind it are dogwood leaves and new (still greenish) flowers. And inside the raindrop is Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Rocks, and Leaning Tower. But wait, there’s more: I’d actually had been working on the image a little while before looking closely at the black shape above Bridalveil Fall and realizing that a raven had flashed into my scene at the instant I clicked (it’s in no other frame). Pretty cool.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, Humor, Macro, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, macro, Photography, raindrop, Yosemite

Favorite: El Capitan Reflection

Posted on April 26, 2014

I can’t believe this image is over ten years old. It represents a significant milestone for me, because I captured it about the time I made the decision to turn a 25+ year serious hobby into my profession. With that decision came the realization that simply taking pretty pictures, or being a very good photographer, wouldn’t be enough—there are plenty of those out there. I made a very conscious decision to start seeing the world differently, to stop repeating the images that I, and other photographers, had been doing for years—no matter how successful they were. I won’t pretend to be the first person to photograph a reflection and ignore the primary subject, but seeing my scene this way represented a breakthrough moment for me.

I’d arrived in Yosemite mid-morning on a chilly November day. A few showers had fallen the night before, scouring all impurities from the air. The air was perfectly still, and the Merced River was about as low (and slow) as it can get. This set of conditions—clean, still air and water—is ideal for for reflections. The final piece of the reflection puzzle, the thing that causes people to doubt at first glance that this is indeed a reflection, was simply lucky timing. I arrived at Valley View that morning in the small window of time when El Capitan was fully lit while the Merced remained in shade, creating a dark surface to reflect my brightly lit subject.

A couple of other things to note, not because I remember my thought process, but because I know how I shoot and like to think that they were conscious choices: First is the way the rock in the foreground is framed by El Capitan’s curved outline—merging the two would have sacrificed depth. That rock, along with the thin strip of misty meadow along the top of the frame, serve as subtle clues that this is a reflection. And second is my f22 choice—believe it or not, even though the entire foreground is just a few feet from my lens, the depth of field is huge. That’s because the focus point of a reflection is the focus point of the reflective subject, not the reflective surface. So, while the El Capitan reflection is at infinity, the closest rock is no more than four feet away. In other words, to be sharp from about four feet all the way out to infinity required a very small aperture and very careful focus point selection. I’m guessing that I focused on the second foreground rock, which was about 7 feet away, to ensure sharpness from about 3 1/2 feet to infinity.

Since this image, reflections have been a personal favorite of mine. I blogged about their power in my “Reflecting on reflections” blog post, and included a sampling of my favorites below.

Photo Workshop Schedule

A Reflection Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, reflection, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, Photography, reflection, Yosemite

A camera’s reality

Posted on April 24, 2014

I knew the dogwood bloom in Yosemite had really kicked in this week (quite early), so when the forecast called for rain in Yosemite on Tuesday, I cleared my schedule and headed up there for the day. It turns out I only got an hour or so of rain and solid cloud cover before the sun came out and started making things difficult, but it was still worth the drive.

On my way out of the park that afternoon I stopped at the Bridalveil Fall view turnout on Northside Drive, spending about an hour lying in the dirt with my 100-400 lens, trying to align dogwood blossoms with Bridalveil Fall (about 1/3 mile away). I found the more impressive aggregation of blooms were about ten feet too far downstream to align perfectly, but as I headed back to my car I took a closer look at a single, precocious little flower in a much more favorable position. I’d overlooked it earlier because, in my haste to get to the more impressive flowers, I wasn’t seeing like my camera. To my human eye, this flower was imprisoned by a jumble of disorganized, distracting stems. But this time I decided to give it a try, knowing that the narrow depth of field of my 100-400 lens would render the scene entirely differently from what my eyes saw.

While the flower is clearly the only point of focus, the way the out-of-focus branches and buds blurred to shapes and accents that actually enhance the image was a pleasant surprise. While Bridalveil softens beyond recognition, I was pretty sure most viewers would still recognize it as a waterfall; even if they don’t, I didn’t think it was a distraction.

Words can’t express how much fun I had playing with this little scene. I’ve been photographing things like this for a long time, but I still find myself caught off guard sometimes by the difference between my vision and my camera’s vision. I love these reminders. I guess if there’s a lesson here, it’s to emphasize how important it is to comprehend and master your camera’s very unique view of the world. Images that achieve that, while nothing like the human experience, are no less “true.” Rather than confirming what we already know, they expand our world by providing a fresh perspective of the familiar.

More rain in the forecast tomorrow—guess where I’ll be….

Raindrops, Dogwood Leaf, Yosemite

When I arrived in Yosemite that morning a light rain was falling. Used my 100mm macro and 20 mm of extension to focus extremely close to this backlit dogwood leaf. It’s difficult to see, but these droplets are actually on the opposite side of the leaf. There is one way to tell—can you see it?

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/200 second

100 mm

ISO 800

F7.1

Category: Bridalveil Fall, Dogwood, How-to, Macro, Yosemite Tagged: dogwood, macro, Photography, Yosemite

Going for bokeh

Posted on April 17, 2014

In this day of ubiquitous cameras, automatic exposure, and free information, a creative photographer’s surest path to unique images is achieved by managing a scene’s depth. Anyone with a camera can compose the left/right/up/down aspect of a scene. But the front/back plane, a scene’s depth, that we human’s take for granted, is missing from a two-dimensional image. Managing depth requires abstract vision and camera control beyond the skill of most casual photographers.

While skilled photographers frequently go to great lengths to maximize depth of field (DOF), many forget the ability of limited DOF to:

- Guide the viewer’s eye to a particular subject

- Provide the primary subject a complementary background

- Provide background context for a subject (such as its location or the time of day or season)

- Smooth a busy, potentially distracting background

- Create something nobody will ever be able to duplicate

They call it “bokeh”

We call an image’s out of focus area its “bokeh.” While it’s true that bokeh generally improves with the quality of the lens, as with most things in photography, more important than the lens is the photographer behind it. More than anything, achieving compelling bokeh starts with understanding how your camera sees the world, and how to translate that vision. The image’s focus point, its depth of field (a function of the f-stop, sensor size, focal length, and subject distance), and the characteristics of the blurred background (color, shapes, lines) are all under the photographer’s control.

No special equipment required

Compelling bokeh doesn’t require special or expensive equipment—chances are you have everything you need in your bag already. Most macro lenses are fast enough to limit DOF, have excellent optics (that provide pleasing bokeh), and allow for extremely close focus (which shrinks DOF). A telephoto lens near its longest focal length has a very shallow DOF when focused close.

Another great way to limit your DOF without breaking the bank is with an extension tube (or tubes). Extension tubes are hollow (no optics) cylinders that attach between your camera and lens. The best ones communicate with the camera so you can still meter and autofocus. Not only are extension tubes relatively inexpensive, with them I can focus just about as close as I could have with a macro. They can also be stacked—the more extension, the closer you can focus (and the shallower your DOF). And with no optics, there’s nothing compromise the quality of my lens (unlike a teleconverter or diopter). But there’s no such thing as a free lunch in photography—the downside of extension tubes is that they reduce the amount of amount light reaching the sensor—the more extension, the less light. On the other hand, since I’m using them to reduce my DOF, I’m always shooting wide open. And the high ISO capability of today’s cameras more than makes up for the loss of light.

Many of my selective focus images are accomplished without a macro or even a particularly fast lens. Instead, preferring the compositional flexibility of a zoom, I opt for my 70-200 f4 (especially) and 100-400 lenses. While my 100 macro is an amazingly sharp lens with beautiful bokeh, I often prefer the ability to isolate my subject, in a narrow focus range, without having to get right on top of it. On the other hand, if I have a subject I want to get incredibly close to, there’s no better way than my macro and an extension tube (or two, or three).

Managing depth of field

When using creative soft focus, it’s important that your background be soft enough that it doesn’t simply look like a focus error. In other words, you usually want your background really soft. On the other hand, the amount of softness you choose creates a continuum that starts with an indistinguishable blur of color, includes unrecognizable but complementary shapes, and ends with easily recognizable objects. Where your background falls on this continuum is up to you.

Your DOF will be shallower (and your background softer):

- The closer your focus point

- The longer your focal length

- The larger your aperture (small f-stop number)

A macro lens and/or extension tube is the best way to get extremely close to your subject for the absolute shallowest DOF. But sometimes you don’t want to be that close. Perhaps you can’t get to your subject, or maybe you want just enough DOF to reveal a little (but still soft) background detail. In this case, a telephoto zoom may be your best bet. And even at the closest focus distances, the f-stop you choose will make a difference in the range of sharpness and the quality of your background blur. All of these choices are somewhat interchangeable and overlapping—you’ll often need to try a variety of focus-point/focal-length/f-stop combinations to achieve your desired effect. Experiment!

Foreground/background

Composing a shallow DOF image usually starts with finding a foreground subject on which to focus, then positioning yourself in a way that places your subject against a complementary background. (You can do this in reverse too—if you see a background you think would look great out of focus, find a foreground subject that would look good against that background and go to work.)

Primary subjects are whatever moves you: a single flower, a group of flowers, colorful leaves, textured bark, a clinging water drop—the sky’s the limit. A backlit leaf or flower has a glow that appears to originate from within, creating the illusion it has its own source of illumination—even in shade or overcast, most of a scene’s light comes from the sky and your subject will indeed have a backlit side. And an extremely close focus on a water droplet will reveal a world that’s normally invisible to the unaided eye—both the world within the drop and a reflection of the surrounding world.

My favorite backgrounds include parallel tree trunks, splashes of lit leaves and flowers in a mostly shaded forest, pinpoint jewels of daylight shining through the trees, flowers that blur to color and soft shapes, sunlight sparkling on water. I also like including recognizable landscape features that reveal the location—nothing says Yosemite like a waterfall or Half Dome; nothing says the ocean like crashing surf.

The final piece of the composition puzzle is your focus point. This creative decision can make or break an image because the point of maximum sharpness is where your viewer’s eyes will land. In one case you might want to emphasize a leaf’s serrated edge; or maybe its the leaf’s intricate vein pattern you want to feature. Or maybe you’ll need to decide between the pollen clinging to a poppy’s stamen, or the sensual curve of the poppy’s petals. When I’m not sure, I take multiple frames with different focus points.

Exposure

Exposing selective focus scenes is primarily a matter of spot-metering on the brightest element, almost always your primary subject, and dialing in an exposure that ensures that it won’t be blown out. Often this approach turns shaded areas quite dark, making your primary subject stand out more if you can align the two. Sometimes I’ll underexpose my subject slightly to saturate its color and further darken the background.

Tripod

And let’s not overlook the importance of a good tripod. In general, the thinner the area of sharpness in an image, the more essential it is to nail the focus point. Even the unavoidable micro-millimeter shifts possible with hand-holding can make the difference between a brilliant success and an absolute failure.

Virtually all of my blurred background images are achieved in incremental steps. They start with a general concept that includes a subject and background, and evolve in repeating click, evaluate, refine, click, … cycles. In this approach, the only way to ensure consistent evolution from original concept to finished product is a tripod, which holds in place the scene I just clicked and am now evaluating—when I decide what my image needs, I have the scene sitting there atop my tripod, just waiting for my adjustments.

Forest Dogwood, Yosemite Valley

I worked this scene for about a half hour before I was satisfied. I started with this dogwood branch and moved around a bit until the background was right. Then I tried a variety of focal lengths to simplify and balance the composition. Once I was satisfied with my composition, I used live-view to focus toward the front of the center cluster. Finally, I ran the entire range of f-stops from f4 to f16, in one-stop increments, to ensure a variety of bokeh effects to choose from.

Bridalveil Dogwood, Yosemite

This raindrop-laden dogwood image uses Yosemite’s Bridalveil Fall as a soft background to establish the location. An extension tube allowed me to focus so close that the nearest petal brushed my lens.

Champagne Glass Poppies, Merced River Canyon, California

The background color you see here is simply a hillside covered with poppies. To achieve this extremely limited DOF, I used an extension tube on my 100mm macro, lying flat on the ground as close as my lens would allow me to focus. Since my tripod (at the time) wouldn’t go that low, I detached my camera, rested the tripod on the ground in front of the poppy, propped my lens on a leg, composed, focused on the leading edge, and clicked my remote release.

Autumn Light, Yosemite

I had a lot of fun playing with the sunlight sneaking through the dense evergreen canopy here, experimenting with different f-stops to get the effect I liked best.

Sparkling Poppies, Merced River Canyon

The background jewels of light are sunlight reflecting on the rippling surface of a creek. I had a blast controlling their size by varying my f-stop.

Dogwood, Merced River, Yosemite

Looking down from the Pohono Bridge, finding the composition was the simple part. But as soon as I started clicking I realized that the sparkling surface of the rapidly Merced River was completely different with each frame. So I just clicked and clicked and clicked until I had over 30 frames to choose between.

Forest Dogwood, Tenaya Creek, Yosemite

Here, rather than background bokeh, I framed my dogwood flower with leaves in front of my focus point.

Bokeh Gallery

Category: aspen, Dogwood, Equipment, fall color, How-to, Macro, Poppies, wildflowers, Yosemite Tagged: dogwood, macro, Photography, Poppies, wildflowers, Yosemite

My photography essentials, part 1

Posted on March 11, 2014

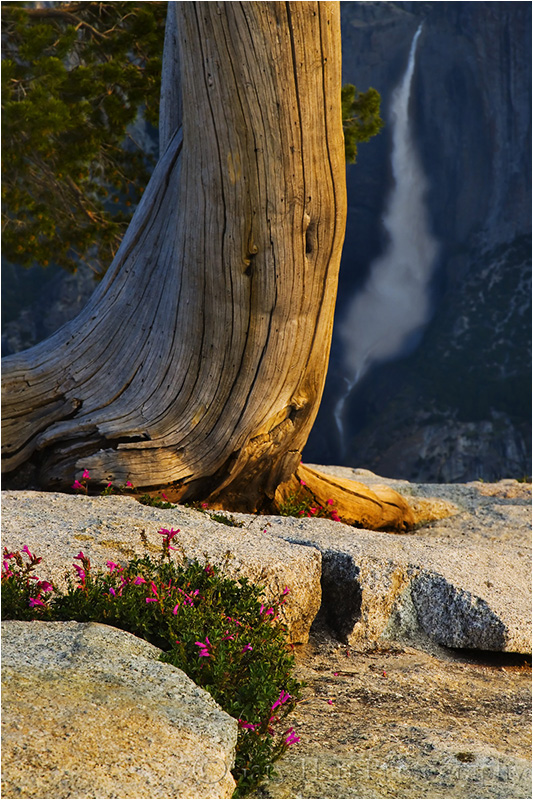

Morning Light, Yosemite Falls from Sentinel Dome, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

1/50 second

F/16

ISO 400

105 mm

A couple of weeks ago the editors at “Outdoor Photographer” magazine asked me (and a few other pros) to contribute to an upcoming article on photography essentials, and it occurs to me that my blog readers might be interested to read my answers. Here’s my answer to the first of their three questions:

1. What are the top three most important pieces of photo gear for you to create your particular style of landscape photography and why is each important?

(Since we all need cameras and lenses, I stuck to optional items.)

- At the top of my list, and it’s not even close, is a tripod/ball-head combo that’s easy to use: sturdy, light, and tall enough to use without a (destabilizing) center post. More than just a platform to reduce vibration, my tripod is a compositional aid that allows me to click a frame, evaluate my image, refine my composition and exposure settings, and click again. I often repeat this process several times until I’m satisfied. Using a tripod, the composition I’m evaluating is sitting right there, waiting for my adjustments; without a tripod, I need to recreate my composition each time. Another unsung benefit of the tripod is the ability to make exposure decisions without compromising f-stop or ISO to minimize hand-held camera shake. I’m a huge fan of Really Right Stuff tripods and heads.

- Adding an L-plate to my bodies was a game-changer—not only does it make vertical compositions more stable, they’re closer to eye level and just plain easier. In my workshops I often observe photographers without an L-plate resist vertical oriented shots, either consciously or unconsciously, simply because it’s a hassle to crank their head sideways, and when they do they need to stoop more. And some heads are not strong enough to hold a heavy, vertically oriented camera/lens combo. But since switching to the L-plate, my decision between a horizontal or vertical composition is based entirely on the composition that works best.

- Given the amount of travel I do, not to mention the hiking once I get there, I need a camera bag that handles all my gear (including my tripod and 15” laptop), has room for extra stuff like a jacket, water, and food, is comfortable for long hikes, durable, easy to access, and (this is huge) fits all airline overhead bins. I’ve tried many, and the F-stop Tilopa is the only one I’ve found that meets all my criteria.

* * *

Because people always seem interested in the equipment I use

For what it’s worth, I have relationships with a few photo equipment vendors that allows them to use my name, and in return I get a price break on their equipment. But I’ve never been one to play the endorsement card to great benefit, or too allow the whole freebie/discount thing affect my recommendations. For example, I’d never heard of F-Stop Gear when they asked if I’d like to be one of their staff pros. When they offered to send me a bag to try, I made it very clear that I’d only use or endorse it if I liked it better than anything else I’ve tried, but they sent it anyway, no strings attached. I’m happy to say that I absolutely fell in love with my F-Stop Tilopa, and haven’t used another bag in over three years (before that I used different bags for different needs).

Likewise, I used (and sung the praises of) Really Right Stuff heads and L-plates long before RRS had ever heard of me. I own four Gitzo tripods, and while I think they’re great, I have to say that my new Really Right Stuff tripod (TVC-24L) is demonstrably better—lighter, sturdier, and easier to use—than my Gitzo 3530LS. And I’ve always found RRS customer service second to none.

Now if I could only get Apple to notice me….

About this image

Follow the light. Here atop Sentinel Dome it would have been easy to concentrate on one or more of a variety of dramatic subjects, including El Capitan, Yosemite Falls, Half Dome, and Cathedral Rocks. But the best light this morning was the warm sunrise glow on an anonymous tree and a clump of wildflowers.

I’d spent the night in the back of my truck a few miles down the road from the Sentinel Dome trailhead. The hike is only about a mile—it’s relatively easy in daylight, but I wanted to be atop the dome about 45 minutes before sunrise, so I did the whole thing in the dark (not something I’d recommend unless you’re extremely familiar with the trail, as I was). Since this was late June, sunrise was around 5:30, which meant an extremely early morning. As it turned out, the sunrise, while magnificent to experience, wasn’t terribly noteworthy photographically.

As I started my walk back to my truck, the light on this tree stopped me. I positioned myself to align the wildflowers, tree, and Yosemite Fall, moving as far back as I could to allow a telephoto that would compress these three primary elements. I dropped low and focused to emphasize the wildflowers and weathered tree in the warm light, relegating unlit Yosemite Falls to background status by allowing it to go slightly soft.

Category: Sentinel Dome, wildflowers, Yosemite, Yosemite Falls Tagged: Photography, Yosemite, Yosemite Falls

It’s Greek to me

Posted on March 3, 2014

Photograph: “Photo” comes from phos, the Greek word for light; “graph” is from graphos, the Greek word for write. And that’s pretty much what we photographers do: Write with light.

Because we have no control over the sun, nature photographers spend a lot of time hoping for “good” light and cursing “bad” light. There’s no universal definition of good and bad light; it’s usually more a function of whatever it is we want to do at the moment. Just as portrait photographers have complete understanding of the artificial light they use to illuminate their subjects, nature photographers should understand the sunlight they photograph: what it is, what it does, and why it does it.

It’s this understanding of light that allows me to be in the right place for vivid sunrises and sunset, to know the best time and location for blurring water, and that helped me anticipate this amazing rainbow. To learn more about light, read the Light article in my Photo Tips section.

About this image

May 26, 2009

On my drive to Yosemite the sky above the San Joaquin Valley was clear, but I was encouraged to see dark cumulus clouds billowing above the Sierra to my east. Sierra thunderstorms in May are rare, but not unprecedented. At the very least I knew the clouds would make for interesting photography. As I entered the park via Big Oak Flat Road, a few large drops dotted my windshield. The afternoon sun was now obscured by clouds, but the sky to the west remained virtually cloudless, a good sign, but nothing I hadn’t seen before.

By the time I reached Yosemite Valley the rain had increased enough to require me to engage my wipers and get my mental wheels turning. I was in the park for a one day, private photo tour with a couple from Dallas. The arrangement was to meet at Yosemite Lodge for dinner to plan the next day’s activities, then to go shoot sunset. As I continued toward my appointment I allowed myself to consider the possibility of a rainbow. Going for it would require rushing to meet my customers, delaying dinner, and possibly sitting in the rain with no guarantee of success.

Still undecided but with about 20 minutes to spare, I dashed up to Tunnel View to survey Yosemite Valley. I liked the way things were shaping up; if I’d have been by myself I’d have skipped dinner. Leaving Tunnel View I continued surveying the sky—by the time I reached the lodge I knew I could be sued for malpractice if I didn’t at least suggest the possibility of a rainbow.

We completed our introductions in front of the cafeteria, but before entering I suggested that maybe we should forget dinner for now. Robert and Kristy were as excited about the conditions as I was (phew) but had just completed a long hike and were famished, so we rushed in and grabbed pre-made pizzas to eat on the road.

Twenty minutes later we were sitting on my favorite granite slope above Tunnel View. We were immediately greeted by a flash of lightning, followed not too many seconds later by a blast of thunder. As a lifelong Californian, I’m not particularly experienced with lightning, so I deferred to the Texans and found comfort in their lack of concern (knowing what I know now, I probably should have been more concerned).

Rainbow photography is equal parts preparation and providence. The preparation comes from understanding the optics of a rainbow, knowing the conditions necessary, where to look, then putting yourself in the best position to capture it; the providence is a gift from the heavens, when all the conditions align exactly as you envisioned. Robert, Kristy, and I had been admiring the view and photographing intermittently in a light, warm rain for about thirty minutes when a rainbow appeared. It started slowly, as a faint band in front of El Capitan, and quickly developed into a vivid stripe of color. For the next seven minutes we shot like crazy people—I varied my compositions with almost every shot and called to them to do the same. When it ended we were giddy with excitement—never let it be said that a professional nature photographer can’t get excited about his subjects—and even though the rainbow never quite achieved a complete arc across the valley, it had been everything I dared hope for.

Little did we know that this first rainbow was just a prelude—less than ten minutes later a second rainbow appeared, becoming more vivid than the first, growing into a full double rainbow that arced all the way across Yosemite Valley, from the Merced River to Silver Strand Fall. It lasted over twenty minutes, long enough for me to set up a second camera and do multiple lens changes on each. We actually reached the point where we simply ran out of compositions and could only laugh as we continued clicking anyway.

One more thing: This is the third time I’ve processed this image. I’ve never been completely happy with some of the color tones and overly bright highlights, so I decided to give it one more shot. Using Lightroom 5 and Photoshop CS 6, I was finally able to come up with something that more accurately represents the experience of this unforgettable moment.

Workshop Schedule

A Gallery of Rainbows

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, How-to, Photography, rainbow, Yosemite Tagged: Photography, Rainbow, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About