Ticket to paradise

Posted on September 11, 2014

Tomorrow I head off to the Big Island for my annual workshop there. Not a bad gig.

One of the great things about Hawaii is the fact that there is no such thing as a private beach—all beaches are open to everyone. Of course that doesn’t give tourists carte blanche to do as they please, and some locals can be pretty territorial about “their” beaches. But I’ve found that if you treat the beaches with respect (leave it as you found it, or better), honor the many areas of spiritual significance (don’t go traipsing through burial grounds and religious sites), and don’t disturb the locals (use your inside voice), most Hawaiians are quite happy to share their beautiful coast and lush rain forests.

Unlike the smooth beaches and gentle surf of the Big Island’s Kona side, the Hilo side is bounded by rugged, volcanic beaches—not great for swimming, but fantastic to photograph. It’s this way because Kilauea has been in some degree of activity for many centuries, and most of this volcanic activity is focused on the Puna Coast south and west of Hilo. The result is pretty much ubiquitous black rock and sand like you see here.

Driving the narrow road that follows the Puna Coast is one of my favorite things to do on the Big Island—on every visit I “discover” another hidden gem (or two) like this. I found this anonymous beach while exploring one afternoon a couple of years ago, and rose early the next morning to get out there for sunrise. Many Hawaii sunrises and sunsets have clouds all the way down to the horizon, but on this morning, much to my delight, the rising sun found its way through a gap in the clouds.

One more thing I love about Hawaii? Well, there’s the ability to photograph sunrise in a tank top, shorts, and flip-flops. Can’t wait….

A Big Island Gallery

(Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show)

Nuts and bolts at the Grand Canyon

Posted on September 4, 2014

Too Close, Twin Lightning Bolts, North Rim, Grand Canyon

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

24-105L

1/8 second

F/18

ISO 100

The bolts started around 1:15; the nuts showed up about ten minutes later. There were 14 of us. We were stationed on the outside viewing deck of the Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim, tripods, cameras, and lightning triggers poised and ready for action. The “action” we were ready for was lightning, and more specifically, the opportunity to photograph it.

The storm had started fairly benignly, poking at South Rim a comfortable distance away, far enough in fact that we heard no thunder. But as often happens, we became so caught up in the intensifying pyrotechnics that we failed to appreciate how much our sky was darkening and that the bolts were in fact landing closer. We continued in exhilarated ignorance until a tripod-rattling thunderclap and simultaneous white flash returned us to the reality of the moment. Hmmm.

By the time the raindrops started plopping, the lightning show had reached such a crescendo that we found all kinds of rationalizations for persistence in the face of potential death: “I think it’s moving west of us,” or, “The lodge’s lightning rods will protect us,” or, “If it were really that dangerous, the hotel staff would make us leave.” (Ummm: When the strikes are that close, it doesn’t matter where the storm is heading; lightning rods are to protect the (smart) people inside the lodge; the hotel staff isn’t paid enough to go outside for anything that risky.) I wish I could say it was common sense that eventually drove us all inside, but the reality is that when the heavy rain finally arrived, it became impossible to keep the front of our lenses dry.

So what is it about danger that brings out the stupid in photographers? I used to be able to use the “I’m from California and we don’t get lightning so I don’t know any better,” defense, but that won’t fly anymore because I do know better: I know a lightning strike can be fatal, and those who survive are often left with a life-long disability; I know that lightning can hit 10 miles from its last strike; I know that if you can hear the thunder, you’re too close.

And it’s not just lightning that brings out the stupid. While chasing potential shots, I know of a photographer who scaled a cliff far beyond my his skill level, drove without hesitation into (but not out of) a raging creek, and became hopelessly mired in mud on a narrow jungle track. And we’ve all read news reports about the photographer plummeting to her death while angling for a better view, or of the partial remains of a photographer discovered in the stomach of an unfortunate grizzly?

We each have our own safety threshold, a comfort zone beyond which we won’t venture. I have a really tough time getting within three feet of any vertical drop greater than 50 feet, but I know photographers who can spit into the Colorado River from the 1,000 foot vertical rim at Horseshoe Bend. On the other hand, I’ve lived in California my entire life and am always disappointed when I miss an earthquake, but I’ve had people tell me they’ll never set foot in the Golden State for fear of a fault slipping.

But back to this lightning thing. It’s not as if I stand on a peak shaking my fist at the sky and dodging bolts like Bowfinger crossing the highway. I will go inside when lightning gets too close—I just think I probably don’t do it quite as soon as I should, and who knows, maybe someday I’ll be sorry (or worse). But I’m happy to report that the score on this particular afternoon was: Photographers—250-ish (the number of images with lightning), Lightning—0 (the number of photographers lost). Next year? Tornados.

A Grand Canyon lightning gallery

The right stuff at the Grand Canyon

Posted on August 28, 2014

I’ve been to the mountaintop

Personal growth should be a lifelong journey. But as a longtime tripod evangelist, I considered many truths carved in stone. Granted, like everyone else, my tripod use (and selection) evolved through my formative photography years. On my path to (perceived) enlightenment, I made the same mistakes most photographers make, mistakes like settling for the tripod I could afford rather than tripod I needed, which only meant spending more money than I would have when I eventually (inevitably) broke down and bought the tripod I needed. And there were those dark years when I believed that in most cases a hand-held shot was just as good as one captured on a tripod. But since my “the center post is more trouble than it’s worth” epiphany about ten years ago, I pretty much believed I knew it all where tripods were concerned.

But last month at the Grand Canyon, I realized that over the last couple of years, some of my tripod truths weren’t immutable as I’d imagined. This was underscored for me during a shoot at Point Imperial, the canyon’s highest vista, when I was able to use my Really Right Stuff tripod and live-view to get shots that wouldn’t have been possible a few years ago.

My (original) tripod commandments

For years my tripod sermon was delivered something like this:

- A tripod for every shot—no exceptions

- Sturdy trumps everything

- Forego the center post—it’s destabilizing, adds extra weight, and makes it impossible to drop your camera to the ground (without a shovel)

- Size does matter—you need a tripod that’s tall enough for you to see through your viewfinder without stooping (without extending the center post)

- Ball-head all the way for landscape shooters (no pan/tilt, no exceptions)

- An L-plate will change your life

Those are the basics; the other tripod variables—cheap vs. light (you can’t have both, no matter what the salesperson or marketing brochure says), three vs. four leg sections, leg-lock design, and collapsed length (for transport in a suitcase or camera bag)—come down to personal preference and budget.

And what’s the big deal about an L-plate?

And L-plate is an L-shaped plate (duh) that attaches at the bottom of your camera and wrapping 90 degrees up one side. It’s really just a two-sided quick-release plate—instead of the standard quick-release that only mounts to the bottom of your camera (forcing you to rotate the head 90 degrees to orient the camera vertically), to orient an L-plate-equiped body vertically, you pop the camera off the head, rotate the camera 90 degrees, and reattach it to the head using the plate’s other side, keeping the head upright (unchanged). Not only does this keep your camera at the same height regardless of its orientation, it’s just much more stable.

Lacking an L-plate, photographers whose tripod is tall enough when the camera is oriented horizontally are sometimes force to stoop or contort when they switch to vertical. Without realizing it, they often compensate for this awkwardness by simply avoiding vertical compositions. I know this because I was one of those photographers—when I switched to an L-plate, my percentage of vertical compositions increased markedly (I actually verified this using Lightroom filters to count the number of horizontal and vertical frames in my library), to the point where my vertical/horizontal images are about 50/50.

What’s your MTH?

By the time they’re serious enough to sign up for a photo workshop, most (but not all) photographers have a sturdy tripod. Still, things aren’t necessarily completely rosy. In addition to a deficient head—either a pan/tilt, or a ball head that’s not strong enough for the camera/lens it’s trying to support (both problems easily solved by going to reallyrightstuff.com and picking the head that best suits your needs, but that’s a discussion for a different day)—a too-short tripod is where I see most novice photographers struggle. Stooping, even just a few inches, may not seem like a big deal at first, but it gets old really fast.

Your minimum tripod height (MTH) is the shortest tripod you can use without stooping or raising the center post. Here are the steps for determining if a trip is tall enough for you:

1. Start with the tripod’s fully extended height (legs extended, center post down), easy to find in the manufacturer’s specifications 2. Add the height of your ball-head (if you have a pan/tilt you need a new head and will be doing this calculation all over again when you get it) 3. Add the distance from the base of your camera to the viewfinderThis gives you the tripod’s maximum usable height. Wait a minute, you say, that’s still not tall enough. To get your MTH, there’s one more step:

4. Subtract 4 inches from your height to account for the distance from the top of your head to your eyes.Old dog, new trick

But in the last year I’ve experienced a minor conversion, opening my mind enough to modify my rigid tripod height recommendations (I used to believe that a tripod that extended above my standing height was unnecessary weight and length)—not only should your tripod be tall enough to use while you stand upright, the ideal tripod is even taller than that, at least 4 inches taller than your viewing height when the legs are planted on flat ground. Extra tripod height allows me to comfortably stand on the uphill side of my camera when the tripod on uneven ground. (If you’re a landscape shooter, how often do you photograph on flat ground?)

Of no less significance is the way a tall tripod allows me to shoot over obstacles. In “ancient” times, photographers needed to to see through their viewfinder to compose and (sometimes) meter, but with the genesis of live-view came the ability to compose and meter without the eyepiece. So while a tall tripod has always been helpful for shooting on level ground, to me this ability to shoot over obstacles is the real game changer.

Going straight to the source

My conversion started with a pilgrimage to Really Right Stuff in San Luis Obispo, about a year-and-a-half ago. I was ready for a new tripod and wanted the best. I’d been quite happy with my Gitzo tripods, but they were purchased before RRS offered tripods—given my long-time experience with RRS heads and L-plates, and what I’d observed in my workshops, I thought I should see whether RRS tripods had supplanted Gitzo at the tripod summit.

RRS doesn’t actually have a retail store, but their beautiful new facility has a nice reception area with many products on display—you might even find the lobby empty when you walk in, but it won’t be long before a door from the back opens and you’ll be greeted by someone who knows more about tripods than you do. My expert was Erik—he spent close to an hour, first patiently demonstrating why the RRS tripods are the best tripods in the world (the comparison was to Gitzo, but his emphasis was on what makes RRS tripods great, rather than what makes Gitzo tripods bad, an approach I appreciated), and then helping me determine which model would best suit me.

I’d arrived with the RRS TVC 33 in mind, but on Erik’s suggestion ended up switching to the RRS TVC 24L Series 2, even though it has four leg sections (extra work extending and collapsing, but more compact when collapsed) and is quite a bit taller than I (believed I) needed. So tall, in fact, that I can almost (but not quite) use it by extending only three leg sections. I’m not going to go into all the reasons I love this tripod (but trust me, I do), but I will say that the extra 8 or so inches above my MTH (I’m about 5’9″) has enabled me to photograph in ways I wouldn’t have been able to do without it.

The paradigm shifting “revelations” I share here (extra-tall is important; Gitzo is no longer the Holy Grail of tripods) apply to photography, but one of the things I love about being forced to reconsider long-held “truths” is the reminder that the instant we believe we have all the answers is the instant we stop growing.

Case in point

All this (finally) brings me to the above image from Point Imperial on my recent Grand Canyon trip. Point Imperial is probably my favorite spot on the North Rim. The railed viewing area isn’t quite large enough for an entire workshop group to work comfortably, but there are enough spots nearby that nobody is disappointed. My favorite location here is on the rocks, just below the railed vista, that jut about 1,000 vertical feet above the canyon. There isn’t a lot of room out here either, and very little margin for error, so after guiding the brave photographers who aren’t afraid of heights out to the edge, I found an out of the way spot a few feet behind them.

It turned out this location was no less precarious than everyone else’s, but being behind the others and a couple of large rocks and shrubs made composing a challenge. Looking around, I decided the best view was on an uneven slope right on the edge, the closer the better. Yikes.

This is where I really appreciated the extra inches my tripod offers. Extending each leg fully, I pushed two legs right up to the edge, keeping myself a safe distance back. With the front (closest to the edge) legs’ planted, to elevate further and get the camera even nearer the edge, pushed the leg closest to me toward the cliff until the other two legs were nearly perpendicular to the ground (directly on the edge). Finally, I leveled the tripod with minor adjustments in the height and placement of the leg closest to me. Once the camera was positioned (about five inches above my eyes), I switched on live-view, composed, metered, and clicked.

As evidenced by the long shutter speed, it was fairly dark when I clicked the image above. Often the best light for photography is opposite the sun after sunset (or before sunrise). The smooth quality of this shadowless light, and the gradual deepening of the rich hues on the horizon, are often missed by the casual observer who is mesmerized by the view toward the setting or rising sun (not possible at Point Imperial at sunset), or unable to appreciate the camera’s ability to bring out more light than the eye can see. But then, you already knew that (right?)….

Extra credit

- Read The tripod difference (why I think every landscape shot should be on a tripod)

- Here’s Thom Hogan’s excellent article on buying a tripod

- Visit the Really Right Stuff website: in addition to the best camera support money can buy, there’s great information here

Roll over Ansel

Posted on August 25, 2014

A few days ago I was thumbing through an old issue of “Outdoor Photographer” magazine and came across an article on Lightroom processing. It started with the words:

“Being able to affect one part of the image compared to another, such as balancing the brightness of a photograph so the scene looks more like the way we saw it rather than being restricted by the artificial limitations of the camera and film is the major reason why photographers like Ansel Adams and LIFE photographer W. Eugene Smith spent so much time in the darkroom.” (The underscores are mine.) Wow, this statement is so far off base that I hardly know where to begin. But because I imagine the perpetuation of this myth must send Ansel Adams rolling over in his grave, I’ll start by quoting the Master himself:

- “When I’m ready to make a photograph, I think I quite obviously see in my minds eye something that is not literally there in the true meaning of the word.”

- “Photography is more than a medium for factual communication of ideas. It is a creative art.”

- “Dodging and burning are steps to take care of mistakes God made in establishing tonal relationships!”

Do those sound like the thoughts of someone lamenting the camera’s “artificial limitations” and its inability to duplicate the world the “way we saw it”? Take a look at just a few of Ansel Adams’ images and ask yourself how many duplicate the world as we see it: nearly black skies, exaggerated shadows and/or highlights, and skewed perspectives. And no color! (Not to mention the fact that an image is a two-dimensional approximation of a three-dimensional world.) Ansel Adams wasn’t trying to replicate scenes more like he saw them, he was trying to use his camera’s unique (not “artificial”) vision to show us aspects of the world we miss or fail to appreciate.

You’ve heard me say this before

The rest of the OP article contained solid, practical information for anyone wanting to come closer to replicating Ansel Adams’ traditional darkroom techniques in the contemporary digital darkroom. But it’s the perpetuation of the idea that photographers are obligated to photograph the world like they saw it that continues to baffle me.

The camera’s vision isn’t artificial, it’s different. To try to force images to be more human-like is to deny the camera’s ability to expand viewers’ perception of the world. Limited dynamic range allows us to emphasize shapes that get lost in the clutter of human vision; a narrow range of focus can guide the eye and draw attention to particular elements of interest and away from distractions; the ability to accumulate light in a single frame exposes color and detail hidden by darkness, and conveys motion in a static medium.

No, this isn’t the way it looked when I was there

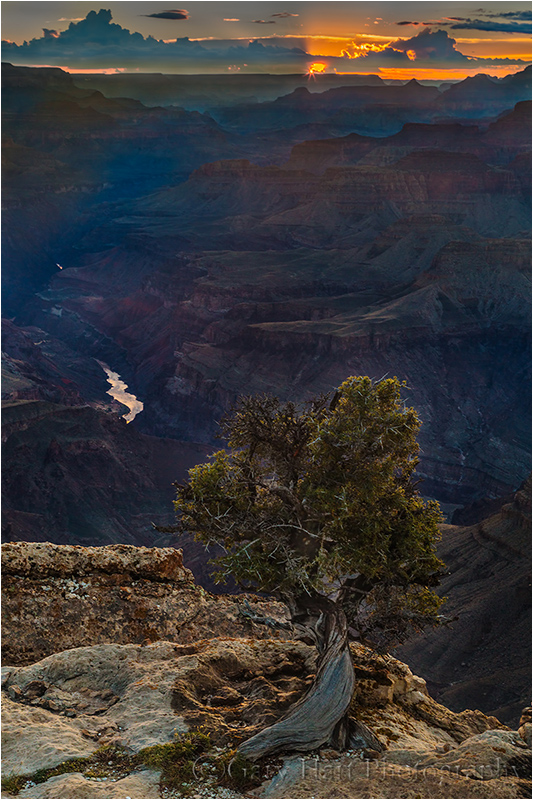

While this sunset scene from Lipan Point at the Grand Canyon is more literal than many of my images, it’s not what my eyes saw. To emphasize the solitude of the lone tree, I allowed the shaded canyon to go darker than my eyes saw it. This was possible because a camera couldn’t capture enough light to reveal the shadows without completely obliterating the bright sky (rather than blending multiple images, I stacked Singh-Ray three- and two-stop hard transition graduated neutral density filters to subdue the bright sky).

To convey a mood more consistent with the feeling of precarious isolation of this weather-worn tree, I exposed the scene a little darker than my experience of the moment. The sunstar, which isn’t seen by the human eye but was indeed my camera/lens’ “reality” (given the settings I chose), was another creative choice. Not only does it introduce a ray of hope to an otherwise brooding scene, without the sunstar the top half of the scene would have been too bland for me to include as much of the shadowed canyon as I wanted to.

I’m not trying to pass this image off as a masterpiece (nor am I comparing myself to Ansel Adams), I’m simply trying to illustrate the importance of deviating from human reality when the goal is an evocative, artistic image. Much as music sets the mood in a movie without being an actual part of the scene, a photographer’s handling of light, focus, and other qualities that deviate from human vision play a significant role in the image’s impact.

A Gallery of My Camera’s World

(Stuff my camera saw that I didn’t)

The right stuff with the left brain

Posted on August 17, 2014

Electric Night, Grand Canyon Lodge, North Rim, Grand Canyon

Canon EOS-5D Mark III

Canon 24-105L

15 1/2 minutes

F/4

ISO 200

Left versus right

Writing about “The yin and yang of nature photography” a couple of weeks ago, I suggested that most photographers are limited by a tendency to strongly favor the intuitive or logical side of their brain (the so-called right-brain/left-brain bias). Today I want to address those intuitive (right brain) thinkers who feel it’s sufficient to simply trust their compositional instincts and let their camera do the thinking.

It was a dark and stormy night

There is absolutely nothing creative about this lightning image from last Monday night at the Grand Canyon. This single click image (one frame—no blending) was captured from the viewing deck of the Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim during a nighttime thunderstorm across the canyon. Compounding the darkness of night and the Grand Canyon’s dark pit were dense clouds that obscured a waning gibbous moon—the canyon so dark that I couldn’t see well enough to create anything. To compose, I simply aimed my camera in the general direction the lightning was most active, clicked, and hoped. The original raw file needed cropping for balance, to remove a few lights from the South Rim Village, and to correct a severely tilted horizon.

Don Smith and I had just brought our workshop group back from a sunset shoot at Point Imperial. Some headed back to their cabins to recover from a day that had started at 4:30 a.m., while a few veered to the “saloon” (it’s not quite as raucous as it sounds) for a beer or glass of wine. Lugging my gear back to my cabin, flashes in the clouds above the lodge indicated lightning was firing somewhere in the distant south and I detoured down to the lodge’s viewing deck to check it out. Through the two-story windows of the inside viewing room and before I even stopped walking I saw bolts landing due south across the canyon, and along the rim down the canyon to the west—violent, multi-stroke bolts that illuminated the clouds and canyon walls with their jagged brilliance.

I set up on the west viewing deck with just enough twilight remaining to compose, starting with a composition I liked—it wasn’t in the direction of the most activity, but I’d already seen a couple of strikes in that direction and was hoping I’d catch a bolt or two. But as the sky darkened and my exposures failed to capture anything, it became clear the activity was shifting west and I’d need to adjust my composition. By then the darkness was nearly complete and I simply centered my frame on the black outline of Oza Butte in front of me, going wide enough to ensure maximum lightning bolt captures.

While finding focus for my earlier compositions had been a little tricky, there had been enough light to make focus manageable. But now the absence of any canyon detail made getting a sharp frame extremely problematic using the conventional focus methods. (Contrary to a misconception that lingers from the old film days, when everyone used prime lenses, you can’t simply dial a zoom lens to infinity and assume you’ll be sharp.)

Once I decided on my composition (and focal length), I pointed my camera (still on the tripod) in the direction of the Grand Canyon Village lights on the South Rim centered the brightest light in my viewfinder. I engaged live-view, magnified the scene 5X, re-centered the target light, magnified 10X (5X and 10X are the two magnification options on my 5DIII), and slowly turned my focus ring until the cross-canyon light shrunk from a soft blur to a distinct point. I then swung my camera back toward my the butte and recreated my composition (without changing my focal length).

Because my earlier exposures had been 30 seconds at ISO 1600 ISO, designed to capture just one or two strikes in a composition I liked, but short enough to adjust things relatively frequently. But since my new strategy was to fire directly into the mouth of the beast, and lacking a composition in which I had any confidence, I decided on a long exposure that would capture enough lightning to overcome the unknown but likely relatively bland composition. Instead of 30 seconds, I wanted at least 12-15 minutes of exposure in Bulb mode (instead of a shutter speed that’s fixed at the moment of the click, in Bulb mode the shutter remains open until I decide it’s time to close it).

“You didn’t tell me there’d be math…”

Doing the math: Because each doubling of the shutter speed adds one stop, a 15 minute exposure would add about (close enough to) 5 stops of light to my original 30 seconds:

- 30 seconds x 2 = 1 minute—1 stop

- 1 minute x 2 = 2 minutes—2 stops

- 2 minutes x 2 = 4 minutes—3 stops

- 4 minutes x 2 = 8 minutes—4 stops

- 8 minutes x 2 = 16 minutes—5 stops

Adding five stops of exposure time meant that keeping the amount of light in my next image unchanged, I’d need to subtract a corresponding 5 stops of light in ISO and/or aperture. But since I thought that my previous exposure was at least a stop too dark, and I guessed that the sky would be darkening even more, I decided to drop only 3 stops, from ISO 1600 to ISO 200 (halving the ISO reduces the light by 1 stop). I made my ISO adjustment, clicked my shutter and locked it open on my remote, checked my watch, then sat back and enjoyed the show.

The 12-15 minute plan was just a guideline—since the difference between 10 minutes and 20 minutes would only be 1 stop, my decision for when to close my shutter had quite a bit of wiggle room. In this case after about 15 minutes I noticed the lightning was slowing down and shifting further west, so I wrapped my exposure and recomposed for my next shot. As it turns out, the next frame only captured a third of the number of strikes this one got because the most intense part of the show was winding down.

The worst is over

If you’re one of those “I have a good eye for composition, but…” folks, congratulations for sticking with me this long. I hope this illustrates for you how important understanding metering and exposure basics, and managing them with your camera, is to maximizing your capture opportunities. This technical aspect of photography isn’t something that should intimidate you—if you can multiply and divide by 2, you have all the math skills you need to figure things out on the fly.

I suspect, and in fact have observed, that most “intuitive” photographers are limited more by their belief that they can’t do the technical stuff than they are by an actual inability to it. What seems to have happened is that they’ve been buried by an avalanche of well-intended but less significant technical minutia covering everything from exposure (e.g., “RGB histograms” and “exposing to the right”), to focus (e.g., “circles of confusion” and “hyperfocal distance”), to printing (e.g., “colorspace” and “monitor calibration”). Many of these things are indeed quite important, but nobody should be expected to tackle them until they have a firm grasp on the basics of metering and exposure, and managing the complementary relationships connecting shutter speed, aperture (measured by f-stops), and ISO. I recommend that you ignore all the other technical buzz until this basic stuff makes sense—not only will you be a better photographer for it, you’ll find that the more “complex” stuff isn’t nearly as complex as it sounds.

Want to learn more?

Try these links:

Then go out in your backyard and practice!

But let’s not forget why we go out with our cameras in the first place

You can’t imagine how thrilling it was to watch these bolts firing several times per minute. Not only were they landing in the direction of my composition, they were also going all along the rim to the west. Witnessing this display was an experience I’ll never forget, and photographing it was a highlight of my photography life.

An Electric Gallery

Release the brocken!

Posted on August 14, 2014

So how cool is this? The shadow is me. It’s called a brocken (named for a mountain in Germany), and the rainbow is a solar glory. This extremely rare phenomenon requires the perfect alignment of sunlight, moisture, and observer, and I just happened to find myself at the fortunate convergence of these conditions.

Yesterday evening Don Smith and I photographed the vestiges of a summer storm at Lipan Point on the Grand Canyon’s South Rim. We were there because Zeus had washed out the overnight trip to Toroweap that Don and I had been planning for many months.

Toroweap is a many-thousand foot vertical drop to the Colorado River on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim, at the end of a 60-mile unpaved road. We’d rented a 4-wheel-drive Jeep for the adventure, but after talking to several Grand Canyon rangers who strongly advised against going out there in the rain. So we jettisoned Plan A and quickly improvised Plan B: leave the relative peace and quiet of the North Rim and jet back to the South Rim (where our next workshop is scheduled to start Friday).

The storm broke during our four-plus hour drive from the North Rim to the South Rim, and we were greeted with the kind of river-hugging, monolith-draping clouds I’m accustomed to seeing after a Yosemite storm. Our first stop was Navajo Point, but after some great shooting there we saw that the cloud making machine was working overtime below Lipan Point, just a short drive down the road.

Arriving at Lipan Point about an hour before sunset, we grabbed our gear and scrambled out to the point beneath the railed (tourist) vista, a rocky, knife-like ridge jutting into the canyon with sheer drops on both sides. I was happily photographing a scene up-canyon when Don called out, “Hey, do you see that?!” I looked up and saw a cloud drifting up from the chasm on our ridge’s east side, no more than 100 feet from us. The cloud was fully lit by the low sun, and right in the middle was my shadow encircled by a full rainbow. I know enough about rainbows to understand what’s going on: a rainbow makes a full circle around the anti-solar point, but terrestrial viewers usually find the bottom half interrupted by the horizon. But understanding a phenomenon doesn’t make me any less awestruck by its manifestation. I’d seen this once before, on a plane taking off through a rainstorm—I looked out the window and saw a rainbow encircling the plane’s shadow, but by the time I retrieved my iPhone the plane banked and I lost it.

But this time I had my camera ready for action—I shifted a few feet up the ridge to juxtapose the rainbow against a snag and clicked away. For my first few frames I stood off to the side and the shadow my camera captured was of my camera on the tripod, so I moved behind my camera and squared my shoulders. Those frames included my outline, but it wasn’t until I spread my arms and legs that I got the shadow you see here.

Read more about rainbows in my Rainbows article in the Photo Tips section.

America’s worst idea

Posted on August 13, 2014

Today’s homework assignment is “A Cathedral Under Siege,” from the August 9 edition of the “New York Times.”

I really don’t have a lot to add to the thoughts expressed in the article, except that if our National Park system is “America’s best idea,” then what is planned for the Grand Canyon may just be America’s worst idea. I only hope that common sense will prevail over the almighty dollar in time to spare this monumental boondoggle from establishing a precedent that threatens every National Park in America.

(Read a little about this image beneath the gallery.)

A National Park Gallery

About this image

Saturday evening Don Smith and I started the first of two, back-to-back Grand Canyon Monsoon photo workshops. Our first sunset shoot at Desert View was nice, but somewhat limited by haze from smoke caused by several managed fires burning near the canyon’s South Rim. Sunday morning we gathered the group at 4:30 and ushered them to Grandview Point, where we were thrilled to find the haze had cleared—in its place we found the Grand Canyon basking between a mix of clouds and clear sky that usually bodes well for a nice sunrise.

We did indeed enjoy beautiful sunrise reds and pinks that morning, but I think my favorite part of the morning came when the sun crested the horizon and in concert with low, broken clouds sent crepuscular rays skimming the canyon. I quickly pointed my camera upstream and worked on a composition to do the moment justice. The towers, bluffs, and buttes on the left were a must, but they carry a great deal of visual weight. To balance the frame I used the shafting sunlight and Colorado River snaking near the frame’s right side. The low hanging clouds provided a perfect ceiling for my frame. And because the combination of bright sky and canyon shadows created a highlight-to-shadow range that exceeded a camera’s ability to capture, I used a three-stop hard transition graduated neutral density filter from Singh-Ray to bring the difference into a manageable range.

(You might also be interested to know that the proposed tram referenced in the article would land just upriver from the segment of the river you see here.)

The yin and yang of nature photography

Posted on August 7, 2014

Clearing Storm, El Capitan and the Merced River, Yosemite

Canon 1Ds Mark III

17 mm

1/8 second

F/11

ISO 100

Conducting photo workshops gives me unique insight into what inhibits aspiring nature photographers, and what propels them. The vast majority of photographers I instruct, from beginners to professionals, approach their craft with either a strong analytical or strong intuitive bias—one side or the other is strong, but rarely both. And rather than simply getting out of the way, the underdeveloped (notice I didn’t say “weaker”) side of that mental continuum seems to be in active battle with its dominant counterpart.

On the other hand, the photographers who consistently amaze with their beautiful, creative images are those who have negotiated a balance between their conflicting mental camps. They’re able to analyze and execute the plan-and-setup stage of a shoot, control their camera, then seamlessly relinquish command to their aesthetic instincts as the time to click approaches. The product of this mental détente is a creative synergy that you see in the work of the most successful photograpers.

At the beginning of a workshop I try to identify where my photographers fall on the analytical/intuitive spectrum and nurture their undeveloped side. When I hear, “I have a good eye for composition, but…,” I know instantly that I’ll need to convince him he’s smarter than his camera (he is). Our time in the field will be spent demystifying and simplifying metering, exposure, and depth management until it’s an ally rather than a distracting source of frustration. Fortunately, while much of the available photography education is technical enough to intimidate Einstein, the foundation for mastering photography’s technical side is ridiculously simple.

Conversely, before the sentence that begins, “I know my camera inside and out, but…,” is out of her mouth, I know I’ll need to foster this photographer’s curiosity, encourage experimentation, and help her purge the rules that constrain her creativity. We’ll think in terms of whether the scene feels right, and work on what-if camera games (“What happens if I do this”) that break rules. Success won’t require a brain transplant, she’ll just need to learn to value and trust her instincts.

Technical proficiency provides the ability to control photography variables beyond mere composition: light, motion, and depth. Intuition is the key to breaking the rules that inhibit creativity. In conflict these qualities are mutual anchors; in concert they’re the yin and yang of photography.

About this image

With snow in the forecast for a December morning a few years ago, I drove to Yosemite and waited out the storm. When the snow finally stopped, I made the best of the three or so hours of daylight remaining.

Rather than return to some of the more popular photo locations, like Tunnel View or Valley View, I ended up at this spot along the Merced River. Not only his is a great place for a full view of El Capitan, it’s also just about the only place in Yosemite Valley with a clear view of the Three Brothers (just upriver and out the frame in this image). Downriver here are Cathedral Rocks and Cathedral Spires.

As I’d hoped, the snow was untouched and I had the place to myself. My decision to wrap up my day here was validated when the setting sun snuck through and painted the clouds gold.

Yosemite Winter

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Staying out of the way

Posted on August 1, 2014

Previously on Eloquent Nature: Road trip!

Sometimes when Mother Nature puts on a show, the best thing a photographer can do is just get out of the way. I’d driven to Mono Lake the previous afternoon to do some night photography and photograph the waning crescent moon before sunrise. After spending the night in the back of my Pilot, I woke at 4:30 and hiked down to the lake. The crescent moon arrived right on time, about an hour before the sun, but I didn’t get any moon images that thrilled me. I was, however, encouraged by the glassy calm of the lake (a distinct change from the previous night) and the promising spread of clouds and sky connecting the horizons.

Waiting in the morning’s utter stillness, it was easy to forget how sleep deprived I was. After fifteen minutes of slow but steady brightening, the color came quickly and for about 30 minutes I was the sole witness to a vivid display that transitioned seamlessly from deep crimson, to electric pink, and finally soft, pastel peach hues. The entire show was duplicated on the lake surface—I could have pointed my camera in any direction to capture something beautiful.

When I get in a situation like this, one that’s both spectacular and rapidly changing, I risk blowing the entire shoot by thinking to much. Thinking in dynamic conditions usually results in things like including foreground elements just because that’s what you’re supposed to do, or spending too much time searching for just the right composition. This problem is particularly vexing at a place like Mono Lake, which is chock full of great visual elements.

I’ve seen many Mono Lake images featuring spectacular color and sparkling reflections, only to be ruined by the inclusion of disorganized or incongruous tufa formations (limestone formations that are the prime compositional element of most Mono Lake images). If you can include the tufa in a way that serves the scene, by all means go for it. But in rapidly changing conditions like I had this morning at Mono Lake, unless I already have my compositions ready, I’m usually more productive when I simplify through subtraction.

This morning I had just enough time before the color arrived to find a spot that didn’t have too much happening in the foreground. Rather than a confusion of tufa formations, I was working with a glassy canvas of lake surface that stretched with little interference to the distant lakeshore. The visual interruptions were few enough, and distant enough, that assembling them into a cohesive foreground was a simple matter of shifting slightly left and right. Handling my shoot this way allowed me to emphasize the scene’s best feature—the vivid color painting the sky and reflecting on the lake. The small tufa mounds dotting the lake surface were relegated to visual resting places that add depth and create virtual lines leading into the scene.

If you look at the images in the Mono Lake Gallery below, you’ll see a variety of foreground treatments that range from simple to complex. The more complex foregrounds are generally the result of enough familiarity and time to anticipate the conditions and assemble a composition. But when I couldn’t find something that worked, I simply stopped trying and allowed the moment to speak for itself.

A Mono Lake Gallery

Road trip!

Posted on July 26, 2014

Sacramento isn’t exactly known for its scenery, but as someone who makes his living photographing nature’s beauty, I haven’t found any place I’d rather live (okay, so maybe Hawaii is close). Just listen to this list of scenic locations I can drive to from home in four hours or less (clockwise from southwest to southeast): Pinnacles National Park, Big Sur, Monterey/Carmel, San Francisco, Point Reyes, Muir Woods (and countless other redwood groves), the Napa and Sonoma Valley Wine Country, the Mendocino Coast, Mt. Shasta, Mt. Lassen National Park, Lake Tahoe, Calaveras Big Trees (giant sequoias), Yosemite, and Mono Lake. Not only is each a destination that draws people from all over the world on its own merits, just check out the visual variety on that list.

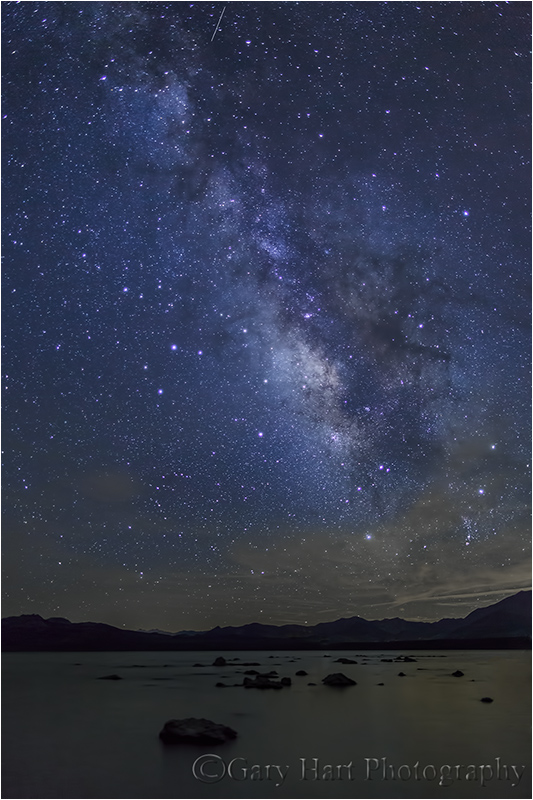

With a crescent moon due to grace last Friday’s pre-sunrise twilight, Thursday morning I checked my schedule and saw nothing requiring my immediate attention. I clicked through my mental location checklist for sunrise spots that offer view of the eastern horizon—Lake Tahoe and Yosemite would work, but they’re both crowded (and I have enough Yosemite crescent moon images anyway). Mono Lake? Hmmmm…. Not only would Mono Lake work for the moon, it should be dark enough there to photograph the Milky Way above the lake. Road trip!

Within a couple of hours my Pilot was packed, and by early afternoon I was motoring up Highway 50. Aside from my photographic ambitions, another highlight of a Mono Lake trip is the drive itself, which takes me near Lake Tahoe, over Monitor Pass, into the Antelope Valley, and finally onto US 395 beneath the sheer east face of the Sierra crest all the way down to Mono Lake and Lee Vining. I pulled into town at about 6 p.m. and after a quick dinner at the Whoa Nellie Deli (not to be missed—look it up), I was off to the lake. Let the adventure begin.

By far Mono Lake’s most photographed location is South Tufa—with great views of the eastern horizon, it certainly would have qualified for my sunrise shoot, but the best views of the Milky Way would require a view toward the southern horizon. Another problem with South Tufa is the crowds, even at night. Not only have I had to contend with light-painters there (sorry, not my thing), one evening I went down there and found the Japanese Britney Spears shooting a video. (That label is my inference—one of the crew confirmed that she was Japanese, the music sounded just like American Top-40 pop of which Britney was the current queen, and judging by the motorhome, full-size bus, two big-rig trucks, and 1/4 mile long cables snaking all the way from the parking lot to the lake, it was pretty clear this girl was a huge star.) So anyway, Thursday evening I simply opted for the view, peace, and quiet of Mono Lake’s north shore.

Traversed only by a disorganized network of narrow, poorly maintained dirt roads, navigating here is difficult even with a high clearance vehicle. While my Pilot is all-wheel-drive, it’s not designed for off road and I need to take these roads with extra care. My strategy at each junction is to take the spur that trends in the direction of the lake, but over the years I’ve become fairly familiar with this side of the lake and had a general idea of where I wanted to be that night. So far I’ve not found a road that will get me much closer than a half mile from the lake, nor have I ever found an actual trail to the lake—when I think I’m close enough to something nice, I just park and walk toward the lake.

It was about a half hour before sunset when I parked my Pilot in a wide spot near the end of a long dirt road. On most visits I’m out there navigating in the dark before sunrise, so it was nice to actually be able see beyond my headlights while hunting for a spot to shoot. Exiting the car I was blasted by the less-than-pleasant but tolerable smell that is distinctly Mono Lake. It’s there year-round, but seems to be worse in summer.

With nothing to block my view, the lake was in clear sight. Lacking a trail, the route is pretty much a matter of picking a point on the shore making a beeline there. My first few steps dropped me down a short but fairly steep slope into the basin of the ancient Mono Lake. From there it flattens to a gentle slope, first through coarse volcanic sand, and then into a band of tall, soggy grass that eventually peters out into a soup of gray muck. Depending on the location I’ve chosen and the lake level at the time of my visit, the consistency of this muck ranges from damp sponge to shoe-sucking wet cement—this year’s muck fell closer to the wet cement side of the continuum, but my high-top Keens were up to the task. And thankfully, I found large areas where the mud had been baked solid enough to walk on without sinking.

The other feature of note out here is the calcium carbonate (limestone) rocks embedded in the lakeshore (they’re the same makeup as tufa, but a different shape than the more striking South Tufa formations). While these make a great platform for sitting and keeping a camera bag out of the mud, in summer they are literally covered with little black alkali flies. Yes, I said literally covered—the flies are so thick that some rocks are black and any shot that includes a rock starts with shoeing the flies if you want to capture it in its natural gray state. (These flies would be a much worse than a mere annoyance if they were capable of flying higher than one foot above the ground.)

My plan for this trip was to photograph sunset, hang out lakeside waiting for dark, do an hour or so of night photography, return to my Pilot and sleep in the back (air mattress and sleeping bag, thank-you-very-much), then rise at 4:30 and return to the lake in time for the moonrise and and sunrise. I made it down to the lake in time to photograph a sunset that was nice but nothing special by Mono Lake standards. As I waited for dark a warm wind whipped the lake surface into a froth, and I soon became concerned about the thin clouds converging overhead—rain was not a concern, but it started to look like my Milky Way aspirations might be thwarted. Nevertheless I hung out (where else was I to go?) and was eventually rewarded when most of the clouds moved on to mess with some other photographer’s plans.

While not nearly as spectacular as my recent Grand Canyon dark sky nights, there were far more stars than any city-dweller can ever hope to see. An occasional meteor darted into view (see the small one at the top of this picture?), and a few satellites drifted overhead, but the main event was the Milky Way, which poured a river of white that spanned the sky from Scorpio in the south to Cassiopeia in the north. While Lee Vining has not quite achieved sky-washing megalopolis status, it nevertheless created an annoying array of discrete light of varying intensity and color that were more than I wanted to try to deal with in Photoshop. But I found that the farther east along the lakeshore I moved, the less these lights aligned with my scene.

I was having so much fun that I stayed out there until the Earth’s rotation had spun the Milky Way into closer alignment with the Lee Vining “skyline,” sometime after 11:00. By then I really had no idea how far east I’d wandered, so as I trudged back to the car in the pitch black I was extremely thankful (and self congratulatory) for the foresight to have mentally registered my bearings in daylight. While my headlamp guided each next step and illuminated the ten-foot radius of my dark world, navigation was solely by the North Star, which I kept off my right shoulder. I had no illusions that this method would allow me to pinpoint the car in the dark, but my hope was to get close enough that clicking my key fob would activate my horn and lights. For quite a while the key was answered by nothing but crickets, and about the time I started worrying that I’d miscalculated my position and would be spending the night in the mud with the flies, my car flashed and beeped about 100 yards to my right. Hallelujah. Not exactly a bullseye, but close enough.

The next morning came much too early, and while I didn’t get any moon pictures that made me particularly happy, the sunrise was off-the-charts and (along with the Milky Way) more than enough justification for an eight hour roundtrip and less than four hours of sleep. But that’s a story for another day.

Photo Tip: Read more about starlight photography