Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

Building a scene

Posted on December 21, 2014

Clearing Storm Reflection, El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall, Valley View, Yosemite

Sony a7R

16 mm

.8 seconds

F/11

ISO 100

Lots of variables go into creating a successful landscape image. Many people struggle with the scene variables—light, depth, and motion—that are managed by your camera’s exposure settings: shutter speed, f-stop, ISO. Others struggle more with the composition variables: identifying, isolating, and framing a subject. (I’m not denying that there’s overlap between the exposure and composition sides of image creation, but leveraging that overlap requires independent mastery of both sides.)

Getting the exposure variables out of the way

Because I want to write more about the composition decisions that went into this image, I’ll only touch briefly on my exposure choices for the above image. I approach every scene with at my camera’s best ISO (100) and lens’s “ideal” f-stop (generally f11, where lenses tend to be sharpest, the depth of field is good, and diffraction is minimal).

Given that motion wasn’t a factor (I was on a tripod, the wind was calm, and the river’s motion didn’t concern me), I stuck with ISO 100. And even though the submerged rocks provided lots of visual interest in the immediate foreground, my 16mm focal length provided more than enough depth of field at f11—focusing about four feet into the scene would give me sharpness from around two feet to infinity. That was easy.

With those two variables established, I spot-metered on the brightest part of the scene and set dialed my shutter speed until the exposure was as bright as felt I could get away with without hopelessly blowing the highlights. This ensured that my scene (shadows included) was as bright as I could safely make it.

Here’s what I was thinking

Reflections of El Capitan, Cathedral Rocks, and Bridalveil Fall make Valley View one of the most photographed locations in Yosemite Valley. I usually I try to find something a little different than the standard view here, but the cloudy vestiges of a passing storm reflecting in the Merced River provide an irresistible opportunity to take advantage of everything that makes Valley View so special.

Some scenes you can walk up to and plant your tripod pretty much anywhere without much difference in your background subjects (though that’s rarely the case with foreground/background relationships). That’s not the case at Valley View, where the difficulty starts with distracting, non-photogenic shrubs on the near riverbank—to keep them out of the frame, you need to hop the rocks all the way down to the river.

The bigger problem at Valley View is getting all the primary elements into the image—too far to the left, and El Capitan disappears behind a stand of evergreens; too far to the right and another stand of evergreens occludes most or all of Bridalveil Fall. I moved into the fifteen-foot section of riverbank that gives me what I consider an adequate view of both, and started studying the submerged and protruding rocks right in front of me, looking for a workable foreground.

I’ll often move around quite a bit to control foreground/background subject relationships; in this case I found little benefit from shifting and stayed more or less in the same place. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t vary my shots—I tried a variety of compositions, but wide and tight, horizontal (above) and vertical (below). Some used lots of sky, while others (like this one) minimized the sky to emphasize the foreground. Still others were of the reflection only, or of the reflections with just a thin stripe of the opposite riverbank. The other variable I played with was my polarizer, which I turned to maximize and minimize the reflection, plus a combination (like both images here).

As with many images, composition at the top of the page required some compromises. I liked the way the vertical version leads the eye through the scene, and frames it with the two most striking elements—El Capitan and Bridalveil Fall. But I also wanted a horizontal rendering that would open up the scene and express its broad grandeur.

An often forgotten component of successful photography is what gets left out—an image’s perimeter are frequently home to distractions overlooked by photographers too drawn to their primary subjects. So the problem making a Valley View horizontal composition that’s wide enough to include the reflection and river rocks, is the introduction of potentially distracting elements on the far left and right.

In this case my greatest problem was the scene’s left side, with its bare trees, brown riverbank, and exposed rocks, it was rife with potential distractions to deal with. Shifting the entire composition to the right would have thrown the frame off balance, and added a lot of real estate that wasn’t worthy of the scene. Going tighter would have sacrificed too much river rock and reflection, an essential feature in my mind. I could have removed my shoes and socks, rolled up my pants, and walked forward through the (frigid) water—that move would have solved all my problems, but probably wouldn’t have been appreciated by all the other nearby photographers.

I ended up using the trees and rocks to frame the left side of the image, taking care to allow the entire arc of the riverbank to complete so it didn’t look like the nearby rocks (on the left) belonged a different scene. The vertical version doesn’t have these problems, and though it sacrifices the breadth of the horizontal composition, hold a gun to my head and I might tell you it’s the vertical version I prefer. (But it’s nice to have a choice.)

A Valley View Gallery

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, How-to, Valley View, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, composition, El Capitan, nature photography, Photography, Valley View, Yosemite

Dialing it in

Posted on December 10, 2014

I’m a big fan of the polarizer, so much so that each of my lenses wears a polarizer that never comes off in daylight. A couple of years ago “Outdoor Photographer” magazine published my article on using a polarizer, a slightly modified version of a blog post that appears in the Photo Tips section of this blog.

If you read that article, or pay much attention to what I write here, you know that while a polarizer can really crank up the blue in your sky, I’m not generally a fan of what the polarizer does to the sky. I find blue sky boring—making it more blue just distracts from my primary subject. And worse still, because polarization varies with the angle of view (maximum polarization occurs when composing perpendicular to the sunlight’s direction, minimum when you’re parallel to the sunlight), wide shots (in particular) display “differential polarization” that manifests as unnatural sky-color variation across the frame.

Where I find a polarizer most indispensable is terrestrial reflections. With a simple twist of a polarizer, a mirror reflection on still water is magically erased to reveal submerged rocks and leaves. More than the reflections we see on still water, a properly oriented polarizer removes distracting, color-robbing glare that jumps off of rocks and foliage. And you don’t need direct sunlight to enjoy a polarizer’s benefits—because reflections and glare exist in overcast and full shade conditions, a polarizer can significantly enhance those images as well.

But back to this differential polarization thing. As most know, a polarizer isn’t a filter that you simply slap on a lens and forget about. A rotates in its frame, changing the amount of polarization on the way—if you’re not orienting (rotating) your polarizer with each composition, you’re better off keeping it in your bag. Watching through your viewfinder as you rotate, you’ll see the scene darken and brighten—maximum polarization occurs when the scene is darkest. These changes may appear subtle at first, and in some cases will be barely visible, but the more you train your eye, the easier it becomes to detect even the most subtle polarization.

Since polarization varies with the angle of view, and any image encompasses a broad angle of view, the amount of polarization you see in any given image varies. While differential polarization is a real pain in images with a uniform surface (like a blue sky), understanding that a polarizer isn’t an all or nothing tool allows you to dial the reflection up in some parts of the scene, and down in others. Rather than automatically dialing the polarizer until the scene darkens (maximum polarization), or until the reflection pops out (minimum polarization), turn the polarizer slowly and watch the reflection advance and retreat as you turn.

That’s exactly what I did with the above image from last week’s Yosemite trip. The sunlit vestiges of a day-long rain swirled above Valley View and reflected in the drought-starved Merced River (one storm does not a drought break). Here I opted for a wide, vertical composition that left room for both foreground and sky tightly framed by El Capitan on the left and Cathedral Rocks and Bridalveil Fall on the right.

Faced with a crisp reflection and a submerged jigsaw of river-worn granite, I refused to choose one or the other. Instead, I composed my scene with a group of exposed rocks to anchor my immediate foreground, then carefully dialed away enough reflection to reveal the rounded rocks, while saving the portion of the reflection that duplicated the Yosemite icons.

I use Singh-Ray filters (polarizers and graduated neutral density)

A selective polarization gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, How-to, Merced River, polarizer, reflection, Valley View, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, nature photography, Photography, polarizer, reflection, Yosemite

Classic Yosemite

Posted on December 3, 2014

December 3, 2014: A brief post to share my workshop group’s good fortune this morning

I’m in Yosemite this week for my Winter Moon photo workshop. Scheduling a December workshop in Yosemite is one of those high risk/reward propositions—I know full well we could get some serious weather that could make things quite uncomfortable for photography, but winter (okay, so technically it won’t be winter for another two-a-half weeks, but it’s December for heaven’s sake, so don’t quibble) is also the best time to get the kind of conditions that make Yosemite special. In the days leading up to the workshop I’d warned everyone about the impending weather, but I’d also promised them that they were in store for something special at some point during their visit. Then I crossed my fingers….

We started Monday afternoon to blue skies and dry waterfalls, but by Tuesday morning the first major storm of California’s (usually) wet season rolled in and everything changed (literally overnight). A warm system of tropical origin, what this storm lacked in snow, it more than made up for in rain, copious rain. Starting before sunrise, we got a little shooting in before the serious stuff started, but the rest of the day was wet, wet, wet. When weather settles in like this, the ceiling drops and Yosemite’s granite features disappear behind a dense, gray curtain. Nevertheless, we found some nice photography and everyone finished the day saturated but satisfied.

This morning (Wednesday) I got the group up to Tunnel View for sunrise, where were met with more of the same—opaque clouds and lots of rain, but little else. Since Tunnel View is usually the best place to wait out a Yosemite storm (thanks to the panoramic view, and the fact that the weather almost aways clears on Yosemite Valley’s west side first), I told everyone we’d just sit tight and see what happens. A few huddled in the cars, but most of the group donned our head-to-toe rain gear and stood out in the rain, waiting (hoping) for the show to begin.

As if on cue, at just about the advertised sunrise time (there was no actual sunrise to witness), the sky brightened and the curtain parted: El Capitan was first on stage, followed closely by a rejuvenated Bridalveil Fall, and soon thereafter the star of the show, Half Dome, appeared center-stage. Radiating from the valley floor, a thick fog rolled across the scene like a viscous liquid, changing the view by the minute—for nearly an hour everyone got to experience a classic Yosemite clearing storm.

As many times as I’ve witnessed a clearing storm from Tunnel View, the experience never fails to thrill me. Overlaying one of the most beautiful scenes on Earth, infinite combinations of cloud, sky, color, and light make each one unique. And as if that’s not enough, sometimes fresh snow, a rainbow, or rising moon are added to the mix. On this morning the clearing was only temporary, with no direct light or hint of blue sky, and the rain soon returned. Not that this was a problem—with more weather in store, this morning just turned out to be the opening act.

Check out my schedule of upcoming photo workshops

A Tunnel View Clearing Storm Gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, Photography Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, clearing storm, El Capitan, Half Dome, nature photography, Photography, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Seeing in the dark

Posted on November 21, 2014

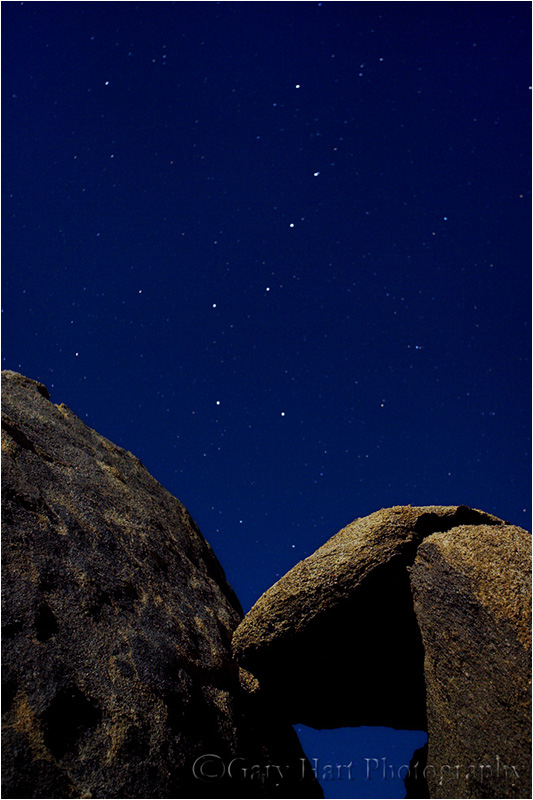

One of the great joys of the digital photography is the ease with which our cameras reveal the world after dark. Scenes that are merely shadow and shape to the human eye are recorded with unseen color and detail by a digital sensor, and stars too faint to compete with moonlight shine brightly.

After a lifetime of refusing to sap my enjoyment of the night sky by attempting to photograph it with film, about ten years ago (a year or two into my personal digital photography renaissance) I decided to take my camera out after dark in the Alabama Hills to photograph Mt. Whitney and the sawtooth Sierra crest. It took just a few frames to realize that this was a new paradigm, but I wasn’t quite hooked until I viewed my images later that night and found, among a host of similarly forgettable Mt. Whitney among snow-capped peak images, one image of the Big Dipper framed by stacked, moonlit boulders that stood out. Ever since I’ve chased opportunities to photograph my favorite scenes after dark—first solely by the light of the full moon, and more recently (as digital sensors improve) by starlight.

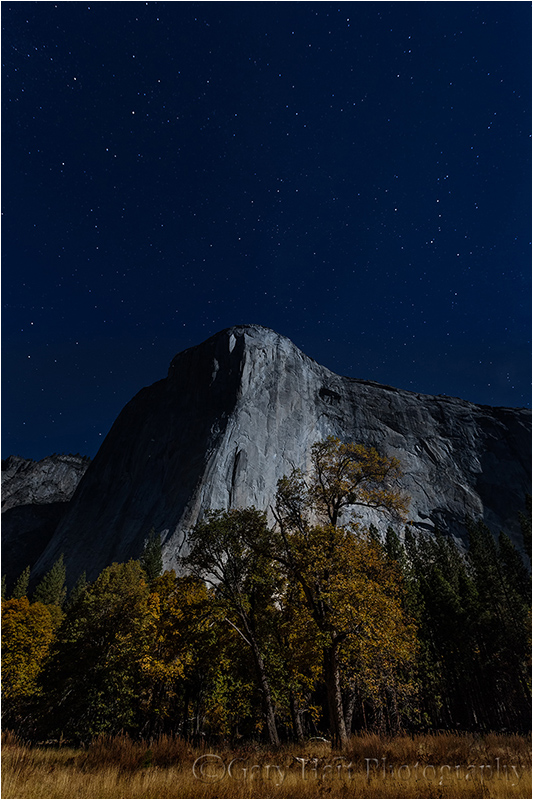

As I incorporate night photography into most of my workshops, I have no qualms about guaranteeing success for all my moonlight shoots (barring equipment failure). This month’s Yosemite Autumn Moon workshop was no exception—after photographing a beautiful full moon rising above Half Dome at sunset, we broke for dinner, then returned to the wide open spaces of El Capitan Meadow beneath El Capitan for a moonlight shoot. One of my favorite things about these moonlight shoots is the way everyone is equal parts surprised and delighted by how simple it is, not to mention how beautiful their images are.

I’d spent time that afternoon getting the group up to speed on moonlight photography (it doesn’t take long), so after a brief refresher on the exposure settings and focus technique, everyone seemed to be managing just fine without me. Feeling just slightly unessential, I decided to try a few frames of my own. Struck immediately with how beautifully the autumn gold stood out, I shifted my position to align the most prominent tree with El Capitan. As with most of my night images, I went vertical to maximize the amount of sky in my frame. I also took care to compose wide enough to include Cassiopeia on the right side of the scene.

If you have a digital SLR and a relatively sturdy tripod, you have everything you need for night photography. I have a couple of articles in my Photo Tips section to guide you: It’s best to start with moonlight photography before attempting the much more challenging starlight photography.

A moonlight gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: El Capitan, fall color, Moonlight, Photography, stars, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, moonlight, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

Moon whisperer

Posted on November 14, 2014

Just when you start getting cocky, nature has a way of putting you back in your place. Case in point: last week’s full moon, which my workshop group photographed to great satisfaction from the side of Turtleback Dome, near the road just above the Wawona Tunnel.

I love photographing the moon, in all of its phases for sure, but especially in its full and crescent phases, when it hangs on the horizon in nature’s best light. I’ve developed a method that allows me to pretty much nail the time and location of the moon’s appearance from any location, and love sharing the moment with my workshop students. (Because my workflow has been in place for about ten years, I don’t use any of the excellent new software tools that automate the moon plotting process.)

Last week’s workshop was no exception, and after much plotting and re-plotting, I decided that rather than my usual Tunnel View vantage point, the view just west of the Wawona Tunnel would work better for this November’s full moon. Arriving about 30 minutes before “showtime,” I gathered everyone around and pointed a spot on Half Dome’s right side, about a third of the way above the tree-lined ridge, and told them the moon would appear right there between 4:45 and 4:50.

Sure enough, right at 4:47 there it was and I exhaled. We photographed the moon’s rise for about 30 minutes, until difference between the darkening valley and daylight-bright moon became too great for our cameras to capture lunar detail. Everyone was thrilled, and I was an instant genius—I believe I even heard “moon whisperer” on a few lips.

The workshop wrapped up the next evening, and I was still basking in my new-found moon whisperer status as I drove home down the Merced River Canyon with my daughter Ashley in the passenger seat. In a car behind us was workshop participant Laurie, who had never been down that road and wanted to follow me to the freeway in Merced.

Hungry, we stopped at one of my favorite spots, Yosemite Bug Rustic Mountain Resort in Midpines (check it out), for dinner. About an hour later, our stomachs full, we were walking back to the cars when someone pointed to a glow atop the mountain ridge above the resort. Ashley and I recognized it as the rising moon, but since this wasn’t a full disk, immediately entered into a friendly debate as to whether the moon was just peeking above the ridge, or had already risen and was disappearing behind a cloud.

We actually got quite scientific, escalating the passion with each point/counterpoint to make our cases (lest you think this was an unfair contest, I should add that Ashley’s a lawyer). Laurie remained silent. I’m not really sure how long we’d been debating when Laurie finally nudged us and pointed skyward, where, in full view of the entire Western Hemisphere, glowed the landscape illuminating spotlight of the actual full moon. Moon whisperer indeed.

(We never did figure out what the glow was.)

A full moon gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and to enjoy the slide show

Category: El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, Humor, Moon Tagged: El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, moon, nature photography, Photography, Yosemite

The yin and yang of nature photography

Posted on August 7, 2014

Clearing Storm, El Capitan and the Merced River, Yosemite

Canon 1Ds Mark III

17 mm

1/8 second

F/11

ISO 100

Conducting photo workshops gives me unique insight into what inhibits aspiring nature photographers, and what propels them. The vast majority of photographers I instruct, from beginners to professionals, approach their craft with either a strong analytical or strong intuitive bias—one side or the other is strong, but rarely both. And rather than simply getting out of the way, the underdeveloped (notice I didn’t say “weaker”) side of that mental continuum seems to be in active battle with its dominant counterpart.

On the other hand, the photographers who consistently amaze with their beautiful, creative images are those who have negotiated a balance between their conflicting mental camps. They’re able to analyze and execute the plan-and-setup stage of a shoot, control their camera, then seamlessly relinquish command to their aesthetic instincts as the time to click approaches. The product of this mental détente is a creative synergy that you see in the work of the most successful photograpers.

At the beginning of a workshop I try to identify where my photographers fall on the analytical/intuitive spectrum and nurture their undeveloped side. When I hear, “I have a good eye for composition, but…,” I know instantly that I’ll need to convince him he’s smarter than his camera (he is). Our time in the field will be spent demystifying and simplifying metering, exposure, and depth management until it’s an ally rather than a distracting source of frustration. Fortunately, while much of the available photography education is technical enough to intimidate Einstein, the foundation for mastering photography’s technical side is ridiculously simple.

Conversely, before the sentence that begins, “I know my camera inside and out, but…,” is out of her mouth, I know I’ll need to foster this photographer’s curiosity, encourage experimentation, and help her purge the rules that constrain her creativity. We’ll think in terms of whether the scene feels right, and work on what-if camera games (“What happens if I do this”) that break rules. Success won’t require a brain transplant, she’ll just need to learn to value and trust her instincts.

Technical proficiency provides the ability to control photography variables beyond mere composition: light, motion, and depth. Intuition is the key to breaking the rules that inhibit creativity. In conflict these qualities are mutual anchors; in concert they’re the yin and yang of photography.

About this image

With snow in the forecast for a December morning a few years ago, I drove to Yosemite and waited out the storm. When the snow finally stopped, I made the best of the three or so hours of daylight remaining.

Rather than return to some of the more popular photo locations, like Tunnel View or Valley View, I ended up at this spot along the Merced River. Not only his is a great place for a full view of El Capitan, it’s also just about the only place in Yosemite Valley with a clear view of the Three Brothers (just upriver and out the frame in this image). Downriver here are Cathedral Rocks and Cathedral Spires.

As I’d hoped, the snow was untouched and I had the place to myself. My decision to wrap up my day here was validated when the setting sun snuck through and painted the clouds gold.

Yosemite Winter

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, Merced River, Photography, reflection, snow, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, nature photography, snow, Yosemite

Favorite: El Capitan Reflection

Posted on April 26, 2014

I can’t believe this image is over ten years old. It represents a significant milestone for me, because I captured it about the time I made the decision to turn a 25+ year serious hobby into my profession. With that decision came the realization that simply taking pretty pictures, or being a very good photographer, wouldn’t be enough—there are plenty of those out there. I made a very conscious decision to start seeing the world differently, to stop repeating the images that I, and other photographers, had been doing for years—no matter how successful they were. I won’t pretend to be the first person to photograph a reflection and ignore the primary subject, but seeing my scene this way represented a breakthrough moment for me.

I’d arrived in Yosemite mid-morning on a chilly November day. A few showers had fallen the night before, scouring all impurities from the air. The air was perfectly still, and the Merced River was about as low (and slow) as it can get. This set of conditions—clean, still air and water—is ideal for for reflections. The final piece of the reflection puzzle, the thing that causes people to doubt at first glance that this is indeed a reflection, was simply lucky timing. I arrived at Valley View that morning in the small window of time when El Capitan was fully lit while the Merced remained in shade, creating a dark surface to reflect my brightly lit subject.

A couple of other things to note, not because I remember my thought process, but because I know how I shoot and like to think that they were conscious choices: First is the way the rock in the foreground is framed by El Capitan’s curved outline—merging the two would have sacrificed depth. That rock, along with the thin strip of misty meadow along the top of the frame, serve as subtle clues that this is a reflection. And second is my f22 choice—believe it or not, even though the entire foreground is just a few feet from my lens, the depth of field is huge. That’s because the focus point of a reflection is the focus point of the reflective subject, not the reflective surface. So, while the El Capitan reflection is at infinity, the closest rock is no more than four feet away. In other words, to be sharp from about four feet all the way out to infinity required a very small aperture and very careful focus point selection. I’m guessing that I focused on the second foreground rock, which was about 7 feet away, to ensure sharpness from about 3 1/2 feet to infinity.

Since this image, reflections have been a personal favorite of mine. I blogged about their power in my “Reflecting on reflections” blog post, and included a sampling of my favorites below.

Photo Workshop Schedule

A Reflection Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, reflection, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, Photography, reflection, Yosemite

Four sunsets, part four: Saving the best for last

Posted on February 23, 2014

Twilight Magic, Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View, Yosemite

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III

3 2/3 seconds

F/11.0

ISO 400

45 mm

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

- Read the second in the series here: Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

- Read the third in the series here: Four sunsets, part three: A marvelous night for a moondance

What I love most about photography is its ability to surprise me. Case in point: the final sunset of my recent Yosemite Horsetail Fall workshop, which delivered just one surprise after another.

I’d told my group that we’d get to photograph another moonrise on our last evening, but only if the clouds cooperated. And as the afternoon wore on, it seemed that the clouds that had cooperated so wonderfully all week wouldn’t be on our side tonight. Assembling everyone on the sloped granite above Tunnel View, I eyed the thin (and shrinking) strip of blue sky on the horizon above Half Dome and checked my watch: 5:10—in about fifteen minutes (less than ten minutes before sunset), with no clouds we’d see a full moon poke into view between Half Dome and Sentinel Dome. But our vantage point gave me a clear view of the clouds racing in that direction and our prospects weren’t good. Rather than stress (much), I stayed philosophical: We’d already had three fantastic sunset shoots, expecting a fourth would be downright greedy.

Nevertheless, it was fun to watch the clouds sprint across the sky and pile up behind Half Dome, changing the scene by the minute. Waiting there, I had thoughts about the throngs gathered on the valley floor, hoping (praying) for Horsetail Fall to light up. My group had been lucky on our first two sunsets, but tonight there’d been no sign of sunlight for at least thirty minutes, and with the cloud machine working overtime behind us, I was pretty certain the Horsetail crowd was in for disappointment.

Anticipating a moonrise, I’d gone up our vantage point with just my tripod, 5DIII, and 100-400 lens. Knowing exactly where the moon would appear, my composition was set well in advance—tight, with Half Dome on the far left and the moonrise point on the far right. But without the moon, I realized that the best shots would likely be wide, so I zipped back to the car and returned with another tripod (doesn’t everyone carry two?), my 1DSIII, and my 24-105. Sitting on the (cold) granite, a tripod on my left and my right, I quickly composed a wide shot with my new setup and resumed my vigilance.

By 5:25 I’d stopped watching the incoming clouds, which were streaming in faster than ever, and turned my focus to the moon’s ground-zero, willing the clouds to part for its arrival. At exactly 5:27 and as if by magic, the white glow of moon’s leading edge burned through the trees downslope from Sentinel Dome. I did a double-take—it was as if the moon had pushed the cloud curtain up and slipped beneath. I shouted, “There it is!” and the furious clicking commenced. We ended with about sixty seconds of moonrise, just long enough for the moon to balance atop the trees, before the clouds settled back into place and snuffed it out.

But the surprises had only just begun. While the whole group still buzzed about the moon, I noticed a faint glow on El Capitan. Not quite believing it (and not wanting to jinx anything), I kept my mouth shut and looked closer. But when the glow persisted, I had to point it out, if for no other reason than confirmation that I wasn’t hallucinating. Within seconds all doubts were dispelled as El Capitan exploded with light from top to bottom. So sudden and intense was the light that I’m surprised we didn’t hear the roar from the Horsetail Fall contingent in the valley below us. And rather than fade, as it often does, the light intensified, warming over the next couple of minutes from amber to orange to red. Soon the color deepened to an electric magenta and spread across the sky and all those clouds I’d been silently cursing just a few minutes earlier became allies, catching the color and reflecting it back to the entire visible world.

Giddy about the show, and focused on my two cameras, I’d long given the moon up for dead. So imagine my surprise when, just as the color reached a crescendo, there the moon was, burning through a translucent veil of clouds. So expansive was the scene that a telephoto couldn’t do it justice, so all of my images following the moon’s resurrection were captured with my 5DIII and 24-105. Exposure became trickier by the minute in the advancing darkness, and eventually, pulling detail from the valley without completely blowing out the moon required a 2-stop hard graduated neutral density filter.

Honestly, this was one of those moments in nature that no camera can do justice. I did my best to come find compositions that captured the majesty of Yosemite Valley, the vivid sky and the way it tinted the entire scene, and that Lazarus moon. But take my word for it, you just had to be there….

* * * *

Four Sunsets

Join me next February when we do it all over again

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, full moon, Half Dome, Moon, Yosemite Tagged: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, moon, Photography, Yosemite

Four sunsets, part two: Classic Horsetail

Posted on February 16, 2014

- Read the first in the series here: Four sunsets, part one: A Horsetail of a different color

While we’d been incredibly fortunate with our Monday night Horsetail Fall shoot, we didn’t get the molten glow everyone covets (though I’d argue, and several agreed, we got something better). Nevertheless, based on the relatively clear skies, I decided to take everyone back for one more try on Tuesday.

On Monday we’d been able to photograph in relative peace from my favorite spot on Southside Drive, but given that the weekend storm had left us in its rearview mirror, and that word had no doubt gotten out that Horsetail Fall was once again flowing, I guessed that the Horsetail day-trippers (Bay Area, Los Angeles, Central Valley photographers who cherry-pick there Yosemite trips based on conditions) would begin crowding into Yosemite Valley. To be safe, I got my group out there a little after 4:00 (sunset was 5:35). Despite being earlier, both parking turnouts were already teeming cars (if everyone squeezes, there might be room for fourteen legally parked cars)—just a few minutes later and we’d not have found room for our three vehicles (all the late arriving cars that had attempted creative, shoulder parking solutions returned to find parking tickets decorating their windshields). With so many more cars, I wasn’t surprised to find my preferred spot down by the river was already starting to fill—but we spread out a bit and everyone managed to squeeze in.

Unlike Monday evening, the Tuesday sky started mostly clear, with only an occasional wisp of cloud floating by. While the scene lacked the drama of Monday, the clear skies boded well for the fiery show we were all there for. We watched the crisp, vertical line separating light and shadow advance unimpeded across El Capitan. The mood was optimistic—borderline festive. Then, a little after five, with no warning the light faded and El Capitan was instantly reduced to a homogeneous, dull gray. Many people reacted as if their team had fumbled on the two yard-line, but those of us who know Horsetail Fall’s fickle disposition just smiled.

In all the years I’ve been photographing Horsetail Fall, I’ve come to recognize how much it likes to tease—while this is more of a gut feeling, it has always seemed to me that the evenings when the shadow marches without pause toward sunset, the light is much more likely to extinguish right before the prime moment. On the other hand, my best success seems to come on the evenings when the light comes and goes, teasing viewers right up until it suddenly reappears in all its crimson glory just before sunset. So, until the light disappeared I was a little concerned that things were going too well. But when the light faded I was able to guide them away from the ledge and reassure them that there’s no reason to panic just yet. And sure enough, about ten minutes later the sunlight came flooding back and everyone exhaled.

As shadow advances from the west, the remaining light warms—by 5:25 it had reached a rich amber. Once it reaches that stage my advice to everyone was that, since the show will either get better (more red) or worse (the light snuffed), and there’s no way of telling which it will be, they should just keep shooting until the light’s gone. And that’s what we did. At first there were no clouds and my composition was fairly tight to eliminate the boring sky. Then, just a few minutes before the “official” 5:35 sunset (I should add that “sunset” when you see it published refers to the time the sun sets below a flat horizon—it set far earlier for those of us on the valley floor, and it wouldn’t set on elevated Horsetail Fall until nearly 5:45), a nice cloud wafted up from behind El Capitan and I quickly went wider to include it.

On the way to dinner with the group I breathed a sigh of relief knowing that my life had just become much easier. For many in the group, what we’d just photographed was their primary workshop objective—for some Horsetail Fall is a bucket-list item. But the nights Horsetail Fall doesn’t light up are far more frequent than the nights it does, and in fact I’ve seen Februarys when it’s only lit up like that once or twice (and I’m sure there have been years when it doesn’t happen at all). While I knew nobody would hold me accountable if Horsetail didn’t put on a show for us, the fact that it did (not to mention the fabulous Horsetail shoot of our first night), meant that I was free to focus the group’s final two sunsets two very special moonrises.

Next up, sunset number three: A marvelous night for a moondance

* * *

Read when, where, and how to photograph Horsetail Fall

Join me next February when we do it all over again

Category: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, Photography, Yosemite

Cliché for a reason

Posted on October 29, 2013

It’s actually even a cliché just to say it, but some things really are “cliché for a reason.” And as much as I try to avoid the cliché shots in Yosemite, sometimes they just can’t be helped.

My Yosemite Fall Color workshop began yesterday, and even though I’d spent all day Saturday in the park, yesterday morning a storm filled Saturday’s blue skies with rain and I felt like I should go check on the conditions before we started. The wet weather had slowed me enough that I didn’t really have time to take pictures, but when I found not only the red and yellow leaves I’d seen on Saturday, and the swirling clouds I’d hoped for, but also Yosemite Valley’s colorful trees and meadows etched with snow, I was tempted at every turn to reach for my camera. Nevertheless, with the exception of a brief breakdown at Cook’s Meadow, I managed to resist temptation.

Unfortunately, the Cook’s Meadow stop had put me even more behind schedule, so I told myself while approaching Valley View that any stop here would be just reconnaissance. And anyway, Valley View images are a dime a dozen, clichés that I’d done more than my share to perpetuate over the years. Then I got there….

I mean seriously, cliché or not (deadline or not), how does a photographer pass up a scene like this? With my group meeting me in just an hour, I really, really didn’t have time for pictures, which is exactly what I kept reminding myself as I leaped from my car, snatched my camera and tripod, and sprinted down to the river. I only snapped four frames, two vertical and two horizontal, before racing back to the car and toward my impending rendezvous.

It’s images like this that remind me that nature’s beauty transcends any human judgement of “cliché.” Pro photographers, myself included, can get a little snobbish about frequently photographed scenes. And while I think it’s important to take the time to find a unique perspective, sometimes it’s best to let Mother Nature speak for herself.

Happy ending

I made it to my workshop with minutes to spare, conducted a lightning-fast orientation, and hustled everyone back outside as quickly as possible. We ended up circling Yosemite Valley several times, photographing without a break until dark. I heard no complaints.

A gallery of clichés

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, fall color, Merced River, reflection, Yosemite Tagged: autumn, El Capitan, fall, Photography, reflection, winter, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About