Moon Over Yosemite

Posted on December 5, 2017

Winter Supermoon, Half Dome, Yosemite

Sony a7RIII

Sony 100-400 GM

Sony 2x teleconverter

ISO 400

f/11

1/8 second

Large or small, crescent or full, I love photographing the moon rising above Half Dome. The alignment doesn’t work most months, so those months when the alignment is right, I do my best to be there.

For last week’s Yosemite Winter Moon photo workshop I’d planned three moonrises: Thursday and Friday we got lucky with the never reliable December skies, but Saturday night concerned me. Not only was this moonrise the “main event,” the forecast was less than promising. And while the first two moonrises were absolutely beautiful, the moon was less full and we were on the valley floor, much closer to Half Dome. Our location required a wider focal length that meant a relatively small moon. But on Saturday (it would rise too late to photograph on Sunday) the moon would be 99 percent full and rise shortly after sunset, just left of Half Dome when viewed from Tunnel View. Tunnel View is eight miles west of Half Dome, a distance, when combined with the moon’s proximity to Half Dome, that would allow a long telephoto that would fill the frame with the moon and all of Half Dome.

Saturday started clear, but soon a thin layer of clouds moved in, bathing Yosemite Valley in diffuse light that was wonderful for photographing pretty much anything that didn’t involve the sky. These clouds weren’t dense enough to completely obscure the sun, but with a chance of rain coming overnight, I knew they’d be thickening at some point.

I got my group in position near Tunnel View about a half hour before sunset. I’ve attempted moonrises that were completely obscured by clouds, and some where we could see the moon’s glow through the clouds, but no detail. I tried to stay positive but the fading light made it impossible to tell exactly how thick the clouds were. Fearing the worst, I rationalized that we’d already had two nice moonrises and maybe wishing for a third was just greedy. But still….

Hoping for the best, I pointed out where the moon should appear about ten minutes after sunset, advising everyone to continue shooting normally until then, but to have an idea of their moonrise compositions. Practicing what I preach, I got out my Sony 100-400 GM, added my 2x teleconverter, and framed up the scene. Because I wasn’t going to shoot anything else (as you may have noticed, I already have a couple of Tunnel View images in my portfolio), I focused and waited.

About five minutes after sunset an amber glow in the clouds next to Half Dome signaled the moon’s imminent arrival. That we could even see any sign of the moon gave me hope and I held my breath as the glow intensified, still unsure whether we’d see lunar detail or just a white blob. The glow was actually unique and very beautiful in its own way and I started clicking. The instant the moon’s brilliant leading edge nudged into view, silhouetting the trees, I knew we were in luck. The landscape was already fairly dark by then, but because this was the group’s third moonrise, they’d become old pros at dealing with the scene’s extreme dynamic range—at that point the workshop’s mantra had become: “Push the exposure until the moon’s highlights start blinking, and fix the shadows in Photoshop.”

The experience that evening was even more spectacular than I had dared hope, a perfect storm of conditions I might never see repeated: the moon’s alignment with Half Dome, the telephoto distance, the timing of the moon’s arrival that put it on the horizon with just enough twilight remaining, and (especially) the translucent clouds that enveloped the moon in a golden halo and eased the scene’s dynamic range.

Some thoughts on the Sony a7RIII

A couple of weeks ago, at a Sony sponsored event in Sedona, I got the opportunity to do some night photography with the new Sony a7RIII. But this Yosemite trip was my first time using the new camera on my own. It’s too soon for any final proclamations, but my general sense is that this camera has even more dynamic range than the a7RII (which is pretty incredible). The other significant takeaway from this weekend is that I used the same battery for three-and-half days and came home with more than 25 percent remaining. Anyone who shot with the a7RII, knows how significant this is.

I’m still getting used to the new camera’s interface—while similar to the a7RII, there are definite differences. I do like the new button layout and improved menu interface, but am still getting used to the joystick and touchscreen—pretty sure I’ll learn to love them too. And the dual card slots are a necessary and most welcome improvement.

My biggest complaint with the new camera is that the back-button focus that I loved so much on the a7rII is broken on the a7RIII. Every camera I’ve ever used (Canon and Sony) has allowed me, after tweaking some settings, to switch seamlessly between auto and manual focus without requiring me to change the focus mode. So the first thing I do when I get a new camera is disengage autofocus from the shutter button and assign autofocus to a button on the back of the camera. With back-button focus enabled, my workflow has always been manually focus by default, but always with the ability to autofocus with the simple push of a button—no focus mode change required. Doing this with the a7RII was the easiest of any camera I’ve ever used, but for some reason Sony changed the focus behavior of the a7RIII, so now I have to deal with the added step of switching focus modes on the camera before focusing. This might not sound like a big deal, but I don’t want to have to think about my camera when I’m composing a scene, so this behavior is extremely frustrating. That said, I’ve already communicated my frustration to Sony’s engineers and am hopeful (confident?) this is a firmware fix that will come soon. Sony’s responsiveness to things like this is one of the reasons I’m so happy I made the switch from Canon.

I’m happily retracting those words after Sony found a solution for the a7RIII back-button focus problem. At last month’s Sony media event Sedona, I was surrounded by Sony’s best and brightest engineers; when I brought the BBF problem to their attention, we all scratched our heads over how to make it work, and they finally asked me to send them a detailed write-up. They promised to address it ASAP, but I didn’t think it would happen without a firmware update.

To enable back-button focus on a Sony a7RIII or a9, simply assign any custom button (Tab 2, Screen 8) to the AF/MF Control Hold option (AF1 screen). To use BBF, keep the camera in Manual Focus mode—this allows you to manually focus with the focus ring, or to autofocus by pressing whatever button you assigned AF/MF Control Hold.

Bottom line

I’m pretty sure this is the best camera I’ve ever had my hands on. In fact, the dynamic range improvement was obvious as soon as I started processing this moonrise shoot—we continued shooting about 25 minutes after sunset, and just a little processing reveals useable detail in my highlights and shadows, even in my final image. Ridiculous.

A couple of full moon photography tips

Sun and moon rise/set times always assume a flat horizon, which means the sun usually disappears behind the local terrain before the “official” sunset, while the moon appears after moonrise. When that happens, there’s usually not enough light to capture landscape detail in the moon and landscape, always my goal. To capture the entire scene with a single click (no image blending), I usually try to photograph the rising full moon on the day before it’s full, when the nearly full (99 or so percent illuminated) moon rises before the landscape has darkened significantly.

The moon’s size in an image is determined by my focal length—the longer the lens, the larger the moon appears. Photographing a large moon above a particular subject requires not only the correct alignment, it also requires distance from the subject—the farther back your position, the longer the lens you can use without cutting of some of the subject.

This moonrise image is a perfect example. Tunnel View in Yosemite is one of my favorite locations to photograph a moonrise because it’s about eight miles from Half Dome. At this distance I can use 500+ mm (250mm plus a 2x teleconverter) to fill my frame with Half Dome—with the moon nearby, I get an image that includes all of Half Dome and a very large moon.

Moon Over Yosemite

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Compromise less, smile more

Posted on November 28, 2017

Night Fire, Milky Way Above Kilauea Caldera, Hawaii

Sony a7S II

Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM

10 seconds

F/2.8

ISO 3200

Night photography always requires some level of compromise: extra equipment, ISOs a little too noisy, shutter speeds a little too long, f-stops a little too soft. For years the quality threshold beyond which I wouldn’t cross came far too early and I’d often find myself having to decide between an image that was too dark and noisy, or simply not shooting at all.

Because the almost total darkness of night photography requires a fast lens, the faster the better, one of the first compromises night photography forced on me was adding a night-only lens—a prime lens that was both ultra-fast and wide. Ultra-fast to maximize light capture, wide enough to give me lots of sky and to reduce the star streaking that occurs with the long shutter speeds night photography requires (the wider the focal length, the less visible any motion in the frame).

I started doing night photography as a Canon shooter, so my first night lens was a Canon-mount Zeiss 28mm f/2.0—it did the job but wasn’t quite as fast or wide as I’d have liked. After switching to Sony I added a Sony-mount Rokinon 24mm f/1.4—I loved shooting at f/1.4, and 24mm was a definite improvement over 28mm, but I still found myself wishing for something wider. And the Rokinon had other shortcomings as well: because the camera doesn’t even know the lens is mounted (f-stop set on the lens, not in the camera), I always had to guess the f-stop I used to capture an image. Worse than that, at f/1.4 the Rokinon had pretty significant comatic aberration that made my stars look like little comets.

Since switching to Sony, one compromise I’ve happily made is carrying an extra body that’s dedicated to night photography. Because the Sony a7S and (later) a7SII are just ridiculously good at high ISO, I was able to compensate for the Rokinon’s distortion by stopping down to f/2 or f/2.8 at a higher ISO. The a7SII is worth the extra weight, but I’ve longed for the day when I could replace the Rokinon lens with something wider, and something that had a better relationship with my camera.

That day came earlier this year, when Sony released the 16-35 f/2.8 GM lens. I got to sample this lens before it was released and was surprised by its compactness despite being so wide and fast—it wasn’t long before the 16-35 f/2.8 GM occupied a full-time spot in my camera bag. And in the back of my mind I couldn’t help thinking that the 16-35 GM might just work as a night lens.

I don’t have the time or temperament to be a pixel-peeper, but I had a sense that this lens was pretty sharp wide open, and few things reveal comatic aberration more than stars. I finally got my chance to test the 16-35 GM lens at night on the Hawaii Big Island workshop in September. When this year’s Milky Way images revealed that the 16-35 GM is sharp and pretty much aberration free at f/2.8, I couldn’t have been happier.

As with every night shoot, this night at the caldera I tried a variety of exposure settings to maximize my processing options later. I was pretty pleased to get a clean exposure at 10 seconds (minimal star motion) and f/2.8 (maximum light). While the a7SII doesn’t even breathe hard at the ISO 3200 I used for this image, I know if I were shooting someplace without its own light source (for example, at the Grand Canyon, the bristlecone pine forest, or pretty much any other location lacking an active volcano), I’d probably need to be at ISO 6400 or even 12800 to make a 10 second exposure work. But it’s nice to know that the a7SII and 16-35 f/2.8 GM will do the job even in darkness that extreme.

One more thing

A couple of weeks ago while in Sedona for Sony I got the opportunity to use the new a7RIII. One highlight of that trip was two night shoots with the new camera. I haven’t had a chance to spend any quality time with those images, but I got the sense that its high ISO performance is nearly as good as the a7SII. If that’s true, that will be one less compromise and a lighter camera bag—at least until Sony releases the a7SIII.

Hawaii Photo Workshops

The Milky Way

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

It’s only cold on the outside

Posted on November 22, 2017

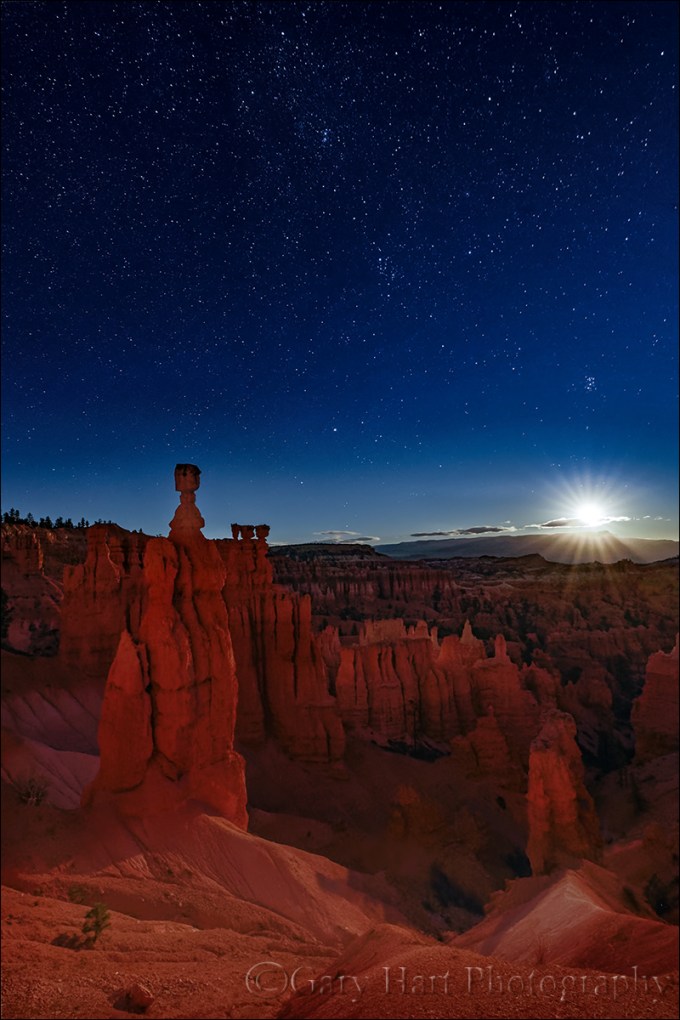

Moonstar, Thor’s Hammer, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah

Sony a7R II

Sony 16-35 f/2.8 GM

30 seconds

F/8

ISO 3200

We all all have different hot/cold comfort thresholds, a temperature above or below which it’s just too hot or cold to feel human. Of course wind and moisture can move the needle a little bit, but let me just say that regardless of the other factors, after spending a few days in Bryce Canyon NP co-teaching a workshop with Don Smith, I’ve determined that the comfort threshold for my California bones is somewhere north of 20 degrees.

That Bryce is cold in November wasn’t really a revelation because couple of Novembers ago I experienced one of the coldest shoots of my life there, a sunrise at Rainbow Point (9,000 feet) where the temperature was 10F and the wind was a constant 35 MPH. Informed by that experience, I showed up this year with full body armor that included multiple layers of silk, wool, down, fleece, and pretty much every other insulation material known to humankind. This visit wasn’t nearly as cold as I experienced a couple of years ago, but layers or not, cold finds exposed skin like a hungry mosquito and virtually ever minute outdoors tested my comfort threshold.

But despite appearances to the contrary, I’m not complaining. Discomfort is part of being a nature photographer, and miserable conditions definitely keep the crowds at bay. These thoughts bring to mind a phenomenon I’ve been aware of my entire photography life: when the shooting is good, the conditions just don’t matter. I’m not saying that I’m not aware that it’s cold, or hot, or wet, I’m saying that good photography somehow turns off the part of my brain that registers discomfort.

On this year’s Bryce visit we had low temperatures in the teens and low twenties, with a little wind. We also had quite a few clouds, but on our last night, when the skies cleared and the stars appeared, Don and I took the group to Thor’s Hammer for a night shoot. With a 95% moon rising more than 90 minutes after sunset, we knew we’d have about an hour or so of quality dark sky photography. The air that night was wonderfully clear, but without the cloud’s insulation, the temperature plummeted as soon as the sun went down and we found ourselves shooting in the coldest temperatures of the trip—somewhere in the teens, I’m certain.

I was well bundled head-to-toe, but gloves and photography don’t mix, especially night photography when you need to locate and adjust all the camera’s controls by feel. So I spent most of the evening with my delicate digits exposed to the elements, full commando. Of course adjusting camera settings with finger-shaped ice cubes is only marginally better than the gloved alternative, but somehow I managed.

It didn’t hurt that the pristine air and remote, moonless darkness made for a dazzling sky. I positioned myself to align Thor’s Hammer with the faint, outward-facing part of the Milky Way in Cassiopeia, trying both vertical and horizontal compositions. Without moonlight, the faint-to-the-eye Milky Way seemed to leap from the blackness on my LCD. Especially exciting were my vertical frames, which revealed near the top the fuzzy disk of the Andromeda Galaxy, our sister galaxy, a mere two-and-a-half million light-years away.

I was having so much fun that I completely forgot how cold I was, and I think that goes for the rest of the group as well. About the time we thought we’d accomplished all there was to accomplish, the clouds on the eastern horizon came alive with the glow of the approaching moon. Everyone seemed to be having such a good time that Don and I decided we should stick around long enough to catch the first rays of moonlight on the red hoodoos.

Most of my full(-ish) moon photography takes place when there’s enough ambient daylight to capture both landscape and lunar detail in a single frame. But since daylight was long gone well before the moon arrived, my exposures that night had been all about maximizing the amount of light reaching my sensor to bring out the foreground. So when the moon showed up my original exposure became far too much and I needed a different plan. I had a couple of options: either find a composition that didn’t include the moon, or figure out a way include the moon in my frame without ruining the picture.

Since the moon was above the best part of the scene, I decided to try for a “moonstar” and repositioned myself to balance it with Thor’s Hammer. Letting the moonlight do the heavy lifting on the hoodoos, I was able to get all the foreground detail I needed, with enough light left over to enhance my moonstar by stopping down to f/8. When we were finished the walk up from Thor’s Hammer is short but steep, perfect for warming my frigid blood, but despited my frozen digits, I honestly have no memory of discomfort.

This was a truly exceptional experience I’ll never forget, a perfect memory to highlight on the eve of Thanksgiving here in America.

A Starry Night Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Photography’s Creativity Triad: Depth

Posted on November 18, 2017

Photography’s Creativity Triad

Enduring photographs don’t duplicate human reality, they reveal unseen aspects of our world. Capturing this hidden world requires mastery of photography’s “creativity triad” that distinguishes the camera’s vision from human vision: motion, light, and depth.

Photography is the futile attempt to squeeze a three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional medium. But just because it’s impossible to truly capture depth in a photograph, don’t think you shouldn’t consider the missing dimension when crafting an image. For the photographer with total control over his or her camera’s exposure variables (what exposure variable to change and when to change it), this missing dimension provides an opportunity to reveal the world in unique ways, or to create an illusion of depth that recreates much of the thrill of being there.

Creative Selective Focus

Poppy Pastel, Sierra Foothills, California (1oomm, f4, ISO 400, 1/125)

A personal favorite solution to the missing depth conundrum I call creative selective focus: An intentionally narrow depth of field with a carefully chosen focus point to flatten a scene’s myriad out-of-focus planes onto the same thin plane as the sharp subject. This technique softens distractions into a blur of color and shape, complementing and emphasizing the subject.

I especially enjoy using creative selective focus for isolation shots of colorful leaves each autumn, and for dogwood and poppy close-ups in spring. Looking for a striking subject that stands out from the surroundings, I position myself to create foreground and/or background relationships that complement my primary subject.

When composing the poppy scene depicted here, I tried to frame the foreground trio of poppies with distant poppies and other wildflowers that I knew would become soft splashes of color. Using a macro lens with extension tubes, a large aperture, and a very close focus point, I achieved a paper-thin range of sharpness that softened the busy background and helped my primary subjects stand out.

A couple of years ago I wrote an article on this very topic for “Outdoor Photographer” magazine. You can read a slightly updated version of this article in my Photo Tips section: Selective Focus.

The Illusion of Depth

Sometimes a scene holds so much near-to-far beauty that we want to capture every inch of it. While we can’t actually capture the depth our stereo vision enjoys, we can take steps to create the illusion of depth. Achieving this is largely about mindset—it’s about not simply settling for a primary subject no matter how striking it is. When you find a distant subject to feature in an image, scan the scene and position yourself to include a complementary fore-/middle-ground subjects. Likewise, when you want to feature a nearby object in an image, position yourself to include a complementary back-/middle-ground subjects.

Autumn Reflection, Half Dome, Yosemite

Guiding my workshop group to a placid bend in the Merced River on this year’s Yosemite Autumn Moon photo workshop, I was instantly drawn to the reflection of Half Dome. The cottonwoods lining the distant shoreline were at their peak autumn gold, and a collection of clouds above Half Dome caught the late afternoon sun, promising good odds for a colorful sunset. These features alone would have made a great image, but I looked around for something to add to the close foreground.

I didn’t need to look long, as just about fifty feet downstream I found a collection of colorful leaves jutting into the river, perpendicular to the shore. I shifted my position until the leaves appeared to point directly at Half Dome and dropped my tripod until my camera was about a foot above the water. With a half hour or so until sunset, I had plenty of time to play with the scene, familiarize myself with all the compositional variables, and refine my composition and focus point. Despite the relative closeness of the floating leaves, at 16mm I knew I had plenty depth of field to carry the entire scene if I was careful. Stopping my lens down to f/16, I focused on a leaf near the middle of the group, about two feet away. This gave me good sharpness from about a foot to infinity and I was in business.

Here’s my Photo Tips article on using hyperfocal focus techniques to enhance your images’ illusion of depth: Depth of Field.

Managing Depth

Photography’s Creativity Triad: Light

Posted on November 11, 2017

Photography’s Creativity Triad

Enduring photographs don’t duplicate human reality, they reveal unseen aspects of our world. Capturing this hidden world requires mastery of photography’s “creativity triad” that distinguishes the camera’s vision from human vision: motion, light, and depth.

Light is arguably the single most important element in an image. And the way a camera handles light may very well be photographers’ single biggest frustration—while our eyes can pluck detail from the deepest shadows to the brightest highlights, with a camera we can have shadows, or we can have highlights, but we can’t have both. Photographers go to great lengths to mitigate the shortcomings of their camera’s dynamic range (range of light a camera can pull detail from in a single frame, from shadows to highlights): Artificial light, blending of multiple exposures, and graduated neutral density filters absolutely have their place, but we often overlook the opportunity limited dynamic range provides.

In my previous post I wrote about how the camera’s ability to accumulate light over the duration of a single frame can reveal motion that’s invisible to the naked eye. Where light is concerned, while many see it as a limitation, I see my camera’s “limited” dynamic range as an opportunity to hide distractions and emphasize features. Whether it’s a Yosemite silhouette that emphasizes shape, or a high-key autumn image that highlights color, narrow dynamic range doesn’t need to be a handicap.

Red Maple Twins, Zion National Park

Last week I was in Zion National Park, co-teaching Don Smith’s workshop there. Zion’s yellows were peaking while we were there, but most of its red maples were about a week past prime. Nevertheless, I was able to find enough crimson leaves to keep me happy.

One morning I found a group of leaves dangling away from most of the tree. Seeking the best way to isolate the leaves from their surroundings, I experimented with different positions and focal lengths, starting with a half dozen or so leaves against a background of soft-focus branches and leaves. I love my new Sony 100-400 GM lens for isolation shots like this and had fun composing these leaves with a variety of focal lengths. The longer I worked on the scene, the more my eye was drawn to the shape, crimson translucence, and vein pattern of one pair of leaves in particular.

Suddenly, simplicity was the operative word. Strategizing the best way to separate these two leaves from their surroundings, I quickly realized a background of more leaves and branches, no matter how soft, was too distracting. But most angles that eliminated background foliage blended my my leaves into Zion’s towering red sandstone walls. Eventually I found a position far enough beneath the tree to put the backlit leaves against the cloudy sky.

Though my Sony a7RII has enough dynamic range to capture the entire range of light from shadows to highlights (with a little help from Lightroom/Photoshop, pulling up the shadows and down the highlights), I found the texture in the clouds almost as distracting as the branches. Instead, I metered on the leaves, which, though nicely backlit, were nowhere near as bright as the sky. My histogram showed that I’d clipped the sky, which I knew would put my leaves against a white background.

With no background detail to blur, I was able to stop down to f/16 and expand my depth of field to get more of both leaves in focus. The downside of this stop-down decision was significantly less light on my sensor, necessitating a longer shutter speed to achieve my desired exposure. For a shutter speed that overcame a breeze wiggling the leaves, I bumped to 1600 ISO. While my plan at capture was to put the backlit leaves against an entirely white background, when I started processing the image, I realized I’d captured a patch of blue sky (revealed by pulling the Lightroom Highlights slider to the left). I decided to keep blue sky while still hiding the texture in the clouds in the “blown” highlights.

Playing with Light

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Photography’s Creativity Triad: Motion

Posted on November 5, 2017

Photography’s Creativity Triad

Enduring photographs don’t duplicate human reality, they reveal unseen aspects of our world. Capturing this hidden world requires mastery of photography’s “creativity triad” that distinguishes the camera’s vision from human vision: motion, light, and depth.

Motion: Autumn Spiral

The human experience of the world unfolds like a seamless movie of continuous instants, while a camera accumulates light throughout its exposure to conflates those instants into a single frame.

Last week in Yosemite I got an opportunity to play with motion while photographing autumn leaves blanketing nearly every exposed surface below Bridalveil Fall. Beneath the fall Bridalveil Creek splits into three branches I love to explore—up- or down-stream, it doesn’t matter—searching for more intimate scenes. Last week I stayed close to the trail—not by design, but because I found enough to occupy every available minute.

Most of the fallen leaves had come to rest on granite, but those that had landed on the creek had been instantly swept downstream until they came to rest in sheltered pools, pushing up against and accumulating the rocks that bounded the pool. I found some pools that were entirely covered with leaves of varying shades of yellow and (just a little) green.

This little scene was downstream from the third bridge. The leaves here had been accumulating in this pool for a few days, leaving it more than half covered on this my final day in Yosemite. More than the golden pool, what really drew my attention from the bridge was a small collection of leaves, soon to become part of the pool’s autumn mosaic, swirling in a slowly spiraling current.

I set up my tripod right on the bridge, pulled out my new Sony 100-400 GM lens, dialed my polarizer to minimize reflections, and went to work. Because so much was happening in the scene, I started toward the lens’s wide end, but quickly found myself tightening each composition until I got down to a version of what you see here.

Once I had my composition, it became all about the motion in the leaves. When photographing landscape subjects in motion, each click can render a completely different image, so I’ve learned to never stop at one (or two, or three…). Whether it’s ocean waves, churning whitewater, or spinning leaves, I always make sure I have a variety of motion effects from which to choose. In this case, while the leaves were spiraling in a fairly consistent current, it seemed that with each rotation at least one leaf would go rogue, either slowing, accelerating, or making a break for the perimeter. The result was a distinctly different spiral with each capture.

I experimented with shutter speeds between ten and thirty seconds. Sometimes I’ll use a neutral density filter to stretch my shutter speed, but for this scene I was using a polarizer (minus two stops), it was quite early (shortly after sunrise) in an always densely shaded location, and darkened even further by the dense clouds of an approaching storm. In other words, the scene was dark enough that I could get the shutter speed all the way out to thirty seconds with my f-stop and ISO settings. When I was done, I had about 20 frames to choose from (one more argument for the tripod), identical except for a little different swirl.

While a still camera can’t capture motion as humans view it, in the right hands the camera absolutely does capture motion in ways that I’d argue can be even more appealing than being there. In this case, the spiral nature of this pool’s motion is much more apparent in this image than it was witnessing it firsthand.

Because there always has to be a moral…

The moral of this story is the importance of being able to manage your exposure variables: You can’t control motion, depth, and light without knowing how to achieve the shutter speed, f-stop, and ISO that serves your creative objective with minimal image quality compromise. That means retaining full control of your exposure settings by shooting in manual, aperture priority, or shutter priority modes. (And if you choose aperture or shutter priority, you must be able to manage your camera’s exposure compensation dial.)

Learn About Photographing Motion

World in Motion

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Yosemite Reflections

Posted on October 28, 2017

Spring Sunset, Leidig Meadow, Yosemite

Sony a7R II

Sony/Zeiss 16-35

3.2 seconds

F/9

ISO 200

Rather than attempt the impossible task of choosing a favorite season in Yosemite, I find it easier to identify the things I like most about each season. From colorful fall to white winter to saturated spring, Yosemite becomes a completely different place with each season. (FYI, summer is for tourists.) But regardless of the season, I think it’s Yosemite’s reflections that make me happiest.

Yosemite’s reflection locations vary with the season. After a storm, small reflective pools form in Yosemite’s ubiquitous granite, then disappear almost as quickly as they appeared. The Merced River, is a continuous ribbon of reflection in the late summer and autumn low-water months, and a churning torrent in spring. But even in those high snowmelt months, reliable pockets of calm can be found along the riverbank, and there are a handful of spots where the river widens and smooths enough to reflect color and shape.

I think my favorite Yosemite reflections may be the ones I find in the flooded meadows during a wet spring, not necessarily because they’re any more beautiful than the other reflections, but mostly because they’re much more rare. Many years we don’t get these vernal pools at all, and even when they do form, their lifetime is measured in days or weeks.

Following years of drought, a record winter snowfall earlier this year translated to a record spring snowmelt, sending the Merced River well over its banks and into many of Yosemite’s normally high-and-dry meadows. This wasn’t “run for your life!” flooding, it was a gradual rise that seeped into and eventually submerged meadows, trails, and even some Yosemite Valley roads.

Leidig Meadow west of Yosemite Lodge is one of those spots that doesn’t usually flood, but flooding here is far from unprecedented. This year when I parked in my usual spot west of the meadow and attempted the normally relaxing 1/4 mile stroll along the river, I had to wade through eight inches of water to make it to the meadow. When I returned a few days later with my workshop group, even after choosing another somewhat less treacherous parking spot, we still had to pick our steps carefully or risk a shoe-full of water.

Meadows are always fragile, but never more-so than when they’re wet, so rather than venture further into the meadow, we set our sights on the numerous reflections among the trees near the (mostly submerged) trail. Even still, we ended up with a number of wet shoes and pant legs, some accidental and some by design (to get the shot, of course).

When it appeared the sunset show was over, the group started to pack up and head back to the cars. About the time I was ready to call it myself, I noticed a little bounce-back pink in the thin clouds overhead and warned everyone that they might be packing it in a little too soon. Many were anxious to get dry and escape the mosquito feast, but those of us who stayed were rewarded with about ten minutes of post-sunset color that went from pale pink to electric magenta, one of those moments in nature that you think just can’t get any better until somehow it does.

Reflecting a bit on reflections

A reflection can turn an ordinary pretty picture into something special. Of course they aren’t always possible, but when the opportunity exists I pursue reflections aggressively, scanning the scene for potentially reflective water and positioning myself accordingly. Too often I see people walk up to a reflection, plop down their tripod, and make a picture of whatever happens to be bouncing off the water at their feet. But maximizing reflection opportunities starts with understanding that, just like a billiard ball striking a cushion, a reflection always bounces off the reflective surface at exactly the same angle at which it arrived.

Armed with this knowledge, when I encounter a reflective surface, I scan the area for something worthy of reflecting. Sometimes that’s easy (Half Dome, for example), sometimes it’s a little tougher (like a rapidly moving sunlit cloud). Knowing that all I need to do is position myself in the path of the reflection of my target subject, I move left/right, forward/backward, up/down until my object appears. I’ve observed that many people are pretty good about the left/right thing, not quite so good with the forward/backward part, and downright miserable at the up/down. But I’ve found that once I get the left/right position nailed, it’s the up/down that makes the most difference.

For example, in the spring reflection of Half Dome at the top of this post, it’s not an accident that the Half Dome and North Dome reflections are centered and uncluttered by all the grass and leaves scattered throughout the water. The centering part was pretty easy, but finding a large enough clean surface to reflect the two domes required a lot of forward/backward maneuvering, combined with frequent up/down dipping—I’m sure to the uninformed observer it appeared that I was trying out a new dance routine.

Read more about reflections

A Gallery of Yosemite Reflections

Playing with my new toy

Posted on October 21, 2017

Leading 15-20 photo workshops per year means coming to terms with photographing the same locations year in, year out. This is not a complaint—I only guide people to locations I love photographing—but it sometimes makes me long for the opportunity to capture something new. Which is why I’m loving visiting my familiar haunts with my newest lenses, the Sony 12-24 G and Sony 100-400 GM. (I’ve had the Tamron 150-600 for a couple of years, but find it too big to lug routinely.)

Back-to-back Eastern Sierra workshops earlier this month meant multiple visits to Mono Lake. My first group hit the jackpot on our South Tufa sunset shoot, finding a glassy reflection (usually reserved for sunrises here) beneath a striking formation of cirrocumulus clouds. Because I was with my group, and I’d guided them all to the spot where the majority wanted to be (justifiable so for first-time visitors), I couldn’t go out in search of something a little different. Instead I just whipped out my 12-24 lens, dropped my tripod to lake-level with one leg in the water, and started composing.

I’m still getting used to shooting at 12mm, which is not only considerably different from what my eyes see, it’s considerably different from what I’ve become used to seeing in my viewfinder (the difference between 16mm and 12mm is huge). The lesson here is the importance of a strong foreground in a wide composition—the wider the focal length, the more important the foreground becomes. Here the entire lakebed was so alive with color and shape, and the water was so still and clear, finding a foreground wasn’t really a problem. I just needed to make sure I organized all the scene’s visual elements into something coherent.

Anchoring my frame with a nearby quartet of small rocks (just a couple of feet away) and a larger protruding lump of tufa a little behind it (everything else in my foreground was submerged), I peered into my viewfinder and quickly decided to go for symmetry with the larger background elements. The clouds couldn’t have been more perfectly positioned—combined with their reflection, they seemed to point directly my composition’s centerpiece, the “Shipwreck” tufa formation (not really an official name, but widely used) that is probably Mono Lake’s most recognizable feature. At 12mm depth of field wasn’t a huge concern—I focused about three feet into the scene and was able to achieve sharpness throughout my frame.

Anyone who has ever been to Mono Lake’s South Tufa can appreciate, looking at this image, how 12mm on a full frame body shrinks distant subjects—the Shipwreck is a very prominent feature here, but the wide lens shrinks it to almost secondary status. On the other hand, dropping down and getting as close as possible to the shore at 12mm really emphasizes the beautiful submerged patterns.

A Mono Lake Gallery

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Don’t believe your eyes

Posted on October 17, 2017

One of the greatest benefits digital photography has over film is the ability it provides to check an image’s exposure at capture (when you can do something about it). But as photographers, we rely so much on our eyes that it’s sometimes difficult to accept that they’re not always right. We take a picture, look at it on the LCD, and decide whether or not it’s perfect without even considering that there might be a better way. But where exposure is concerned, there is indeed a better way.

That’s because every picture you click, whether raw or jpeg (but especially raw), contains more shadow and highlight information than the jpeg that appears on your camera’s LCD preview screen can reveal. Fortunately, our digital cameras give us a tool that tells us about that missing exposure info: the histogram.

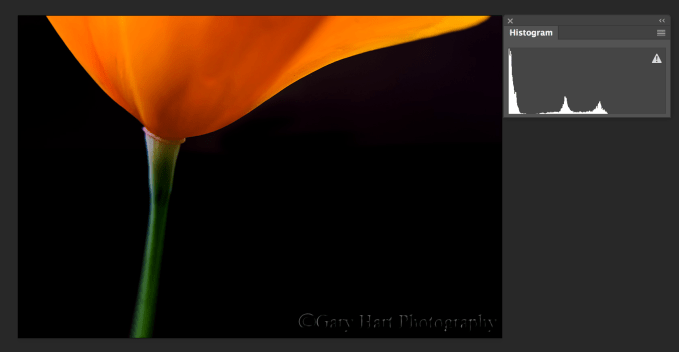

Histogram explained

Simple Histogram: The shadows are on the left and the highlights are on the right; the far left (0) is absolute black, and the far right (255) absolute white.

A histogram is a graph of the tones in an image. While I imagine that any graph has the potential to evoke high school science trauma flashbacks, a histogram is really quite simple, simple enough to be read and interpreted in the blink of an eye. And not only is your histogram easy to read, it’s really the most reliable source of exposure feedback.

When an image is captured on a digital sensor, your camera’s “brain” samples each photosite (the individual pixels in the megapixel number used to measure sensor resolution), determining a brightness value that ranges from 0 (black) to 255 (white). Every brightness value from 1 to 254 is a shade of gray—the higher a photosite’s number, the brighter its tone.

Armed with the brightness values for each photosite in the image, the camera is ready to build the image’s histogram. The horizontal axis of the histogram has 256 discrete columns (0-255), one for each possible brightness value, with the 0/black column on the far left, and the 255/white column on the far right (they don’t display as individual columns because they’re crammed so close together).

Despite millions of photosites to sample, your camera builds a new histogram for each image instantly, quickly adding each photosite’s brightness value to its corresponding column on the histogram, like stacking poker chips—the more photosites of a particular brightness value, the higher its corresponding column will spike.

Reading a histogram

The version of a picture that displays on your camera’s LCD is great for checking the composition, but the range of tones you can see in your LCD preview image varies with many factors, such as the camera’s LCD brightness setting and the amount of ambient light striking the LCD. Most important, because there’s more information in captured than the LCD preview can show even in the best conditions, you’ll never know how much recoverable data exists in the extreme shadows and highlights by relying on the LCD preview.

It’s human nature to try to expose a scene so the camera’s LCD image looks good, but an extreme dynamic range image that looks good on the LCD will likely have unusable highlights or shadows. As counterintuitive as that feels, exposing an image enough to reveal detail in the darkest shadows brightens the entire scene (not just the shadows), likely pushing the image’s highlights to unrecoverable levels. And making an image dark enough on the LCD to salvage bright highlights darkens the entire scene, all but ensuring that the darkest shadows to be too black. In fact, a properly exposed extreme dynamic range scene (a scene with both bright highlights and dark shadows, such as a sunrise or sunset) will look awful on the LCD (dark shadows and bright highlights). The histogram provides the only reliable representation of the tones you captured (or, in your live-view LCD display or mirrorless electronic viewfinder, of the tones you’re about to capture).

There’s no such thing as a “perfect” histogram shape. Rather, the histogram’s shape is determined by the distribution of light in the scene, while the left/right distribution (whether the graph is skewed to the left or right) is a function of the amount of exposure you’ve chosen to give your image. The histogram graph’s height is irrelevant—information that appears cut off at the top of the histogram just means the graph isn’t tall enough to display all the photosites possessing that tone (or range of tones).

When checking an image’s histogram for exposure, your primary concern should be to ensure that the none of the tone data is cut off on the left (lost shadows) or right (lost highlights). If your histogram appears cut-off on the left side, shadow detail is so dark that it registers as black. Conversely, if your histogram appears cut off on the right side, highlight detail is so bright that it registers as white.

Managing a histogram

In a perfect world, when you see your histogram cut off on the left (everything cut off on the left is detail-less black), you simply increase the exposure until the histogram shifts right (brighter) far enough that no shadow data is cut off. And if you see your histogram is cut off on the right, you decrease the exposure until the histogram shifts left (darker) enough that no highlight detail is cut off. Problem solved.

But many scenes contain a broader range of light, from the darkest shadows to the brightest highlights, than the camera can handle. In these scenes you can blend multiple exposures that cover the entire range of tones, apply a graduated neutral density filter (to moderate the sky). When those options aren’t available or practical, I usually save the highlights and sacrifice the shadows.

While the general goal is to ensure that none of the tone data is cut off on the left or right side of the histogram, the exposure you choose for a scene is ultimately a creative choice that isn’t bound to the way the scene looks to your eye. Though I often expose my scenes to match the amount of light my eyes see, sometimes I decide to make the scene darker or brighter than what I see.

- Evenly distributed histogram

- Intentionally bright histogram

- Intentionally dark histogram

A picture is worth a thousand words

Trusting a histogram over a picture you can actually see requires a leap of faith. I can explain the concept until I’m blue in the face, but in my workshops the point doesn’t usually hit home without a demonstration. For example, the two Horseshoe Bend sunstar images below are from the same file—on the left is the way the picture looked when I captured it, along with its histogram; on the right is the same picture with just a few minutes of very basic processing in Lightroom and Photoshop (no plugins, blending, or any other elaborate processing).

If I’d have exposed this scene bright enough for the shadows to look good on my LCD (more like my eyes saw them), the highlights would have been hopelessly overexposed (white); if I’d have darkened my highlights enough to look good on my LCD, the shadows would have darkened to an unrecoverable black. I knew my best chance for capturing this high dynamic range scene with a single click was to ignore the LCD and trust the histogram.

Despite an image that didn’t look good at all on my LCD, the histogram on my Sony a7R II showed me that I’d captured virtually all of the scene’s shadows and most of its highlights. And because I captured this image in raw mode, I was confident that I had even more shadow and highlight information than my histogram indicated, a fact instantly confirmed with a rightward tug of Lightroom’s Shadows slider. With minimal processing effort, I was able to achieve final result you see here. (This is why landscape photographers are always begging for cameras with more dynamic range, and also why I use the Sony a7RII.)

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

Trusting My Histogram

Photograph the Eastern Sierra

Posted on October 10, 2017

First Light, Lone Pine Peak and Mt. Whitney, Alabama Hills, Eastern Sierra (2006)

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II

Canon 70-200 f/4L

1/20 second

F/8

ISO 200

This is an edited and updated version of my Eastern Sierra article that appeared in the September 2016 edition of “Outdoor Photographer” magazine

Eastern Sierra

Skirting the east side of the Sierra Nevada, US 395 enchants travelers with ever-changing views of California’s granite backbone. Unlike anything on the Sierra’s gently sloped west side, Highway 395 parallels the range’s precipitous east flank in the shadow of jagged peaks that soar up to 2 miles above the blacktop. More than just beautiful, these massive mountains form a natural barrier against incursion from the Golden State’s major metropolitan areas, keeping the Eastern Sierra region cleaner and quieter than its scenery might lead you to expect.

It would be difficult to find any place in the world with a more diverse selection of natural beauty than the 120-mile stretch of 395 between Lone Pine and Lee Vining: Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, the ancient bristlecones of the White Mountains (across the Owens Valley, east of the Sierra), the granite columns of Devil’s Postpile, Mono Lake and its tufa towers, and too many lake-dotted, aspen-lined canyons to count. Long a favored escape for hikers, hunters, and fishermen, in recent years photographers have come to appreciate the rugged, solitary beauty possible only on the Sierra’s sunrise side.

I prefer photographing most Eastern Sierra locations at sunrise, when the day’s first rays paint the mountains with warm light, and the highest peaks are colored rose by alpenglow. (Without clouds, Eastern Sierra sunset light can be tricky, as you’ll be photographing the shady side of the mountains against the brightest part of the sky.) Devoid of large metropolitan areas, low light pollution also makes the Eastern Sierra one California’s finest night photography destinations. But regardless of the time of day, the key to photographing the Eastern Sierra is flexibility—if you don’t like the light in one direction, you usually don’t need to travel far to find something nice in another direction.

Lone Pine area

The southern stretch US 395 bisects the Owens Valley, a flat, arid plane separating the Sierra Nevada to the west from the Inyo ranges to the east. Just west of Lone Pine lies the Alabama Hills. Named for a Confederate Civil War warship, the Alabama Hills’ jumble of weathered granite boulders and proliferation of natural arches would be photogenic in any setting. Putting Mt. Whitney (the highest point in the 48 contiguous states), Lone Pine Peak (the subject of Mac OS X Sierra’s desktop image), and the rest of the serrated southern Sierra crest seems almost unfair.

The Alabama Hills are traversed by a network of unpaved but generally quite navigable roads. To get there, drive west on Whitney Portal Road (the only traffic signal in Lone Pine). After 3 miles, turn right onto Movie Road and start exploring. If you’re struck by a vague sense of familiarity here, it’s probably because for nearly a century the Alabama Hills has attracted thousands of movie, TV show, and commercial film crews.

Mobius Arch (also called Whitney Arch and Alabama Hills Arch) is the most popular photo spot in the Alabama Hills. It’s a good place to start, but settling for this frequently photographed subject risks missing numerous opportunities for truly unique images here. To get to Mobius Arch, drive about a mile-and-half on Movie Road to the dirt parking area at the trailhead. Following the marked trail down and back up the nearby ravine, the arch is an easy ¼ mile walk. There’s not a lot of room here, but if the photographers work together it’s possible to arrange four or five photographers on tripods with Mt. Whitney framed by the arch. And don’t make the mistake many make: the prominent peak on the left is Lone Pine Peak; Mt. Whitney is serrated peak at the back of the canyon.

Sunrise is primetime for Alabama Hills photography, but good stuff can be found here long before the sun arrives. I try to be set up 45 minutes before the sun (earlier if I want to ensure the best position for Whitney Arch) to avoid missing a second of the Sierra’s striking transition from night to day.

The grand finale from anywhere in the Alabama Hills is the rose alpenglow that colors the Sierra crest just before sunrise. Soon after the alpenglow appears, the light will turn amber and slowly slide down the peaks until it reaches your location, warming the nearby boulders and casting dramatic, long shadows. But unless there are clouds to soften the light, you’ll find that the harsh morning light will end your shoot pretty quickly once the sunlight arrives on the Alabama Hills.

Whitney Portal Road (closed in winter) ends about 11 miles beyond Movie Road, at Whitney Portal, the trailhead for the hike to Mt. Whitney and the John Muir Trail. On this paved but steep road, anyone not afraid of heights will enjoy great views looking east over the Alabama Hills and Owens Valley far below, and up-close views of Mt. Whitney looming in the west. At the back of the Whitney Portal parking lot is a nice waterfall that tumbles several hundred feet in multiple steps.

The Alabama Hills are one of my favorite moonlight locations. Because the full moon rises in the east right around sunset, on full moon nights the Alabama Hills and Sierra crest are bathed in moonlight as soon as darkness falls. Lit by the moon, the hills’ rounded boulders mingle with long, eerie shadows, and the snow-capped Sierra granite radiates as if lit from within.

If you find yourself with extra time, drive about 30 miles east of Lone Pine on Highway 136 until you ascend to a plain dotted with photogenic Joshua trees—after you’ve finished photographing the Joshua trees, turn around and retrace the drive back to Lone Pine on 136 to enjoy spectacular panoramic views of the Sierra crest. And just north of Lone Pine on 395 is Manzanar National Historic site, a restored WWII Japanese relocation camp. Camera or not, this historic location is definitely worth taking an hour or two to explore.

Bristlecone pine forest

Continuing north from Lone Pine on 395, on your left the Sierra stretch north as far as the eye can see, while the Inyo mountains on the right transition seamlessly to the White Mountains. Though geologically different from the Sierra, the White Mountains’ proximity and Sierra views make it an essential part of the Eastern Sierra experience.

Clinging to rocky slopes in the thin air above 10,000 feet, the bristlecone pines of the White Mountains are among the oldest living things on earth—many show no signs of giving up after 4,000 years; at least one bristlecone is estimated to be 5,000 years old.

Abused by centuries of frigid temperatures, relentless wind, oxygen deprivation, and persistent drought, the bristlecones display every year of their age. Their stunted, twisted, gnarled, polished wood makes the bristlecones suited for intimate macros and mid-range portraits, or as a striking foreground for a distant panorama.

The two primary destinations in the bristlecone pine forest are the Schulman and Patriarch Groves. Get to the bristlecone pine forest by driving east from Big Pine on Highway 168 and climbing about 13 car-sickness inducing miles. Turn left on White Mountain Road and continue climbing another 10 twisting miles to reach the Schulman Grove. Despite the incline and curves, the road is paved all the way to this point. Stop at the Sierra panorama after about 8 miles for a spectacular view that also makes a great excuse to pause and collect yourself.

Stop at the small visitor center in the Schulman Grove to pay the modest use fee, then choose between the 1-mile Discovery loop trail, and the 4 1/2 mile Methuselah loop trail. Both trails are in good shape, but the extreme up and down in very thin air will test your fitness. Most of the trees on the Methuselah Trail get more morning light, while the majority of the Discovery Trail trees get their light in the afternoon.

If you’re unsure of your fitness, or have limited time, the Discovery Trail is definitely the choice for you. Because the photogenic trees start with the very first steps, on this trail you can turn around at any point without feeling cheated of opportunities to photograph nice bristlecones. And along the way you’ll appreciate the handful of benches for enjoying the view and catching your breath. Hikers who can make it to the top of the switchbacks are rewarded great views of the snow-capped Sierra across the Owens Valley.

The Discovery Trail climbs for a couple hundred more yards beyond the switchbacks, but just as you’re beginning to wonder whether all the effort is worth it, the trail levels, turns, and drops. Soon you’ll round a 90-degree bend and be rewarded for your hard work with two of the most spectacular bristlecones in the entire forest. Spend as much time here as you have, because the rest of the loop back to the parking lot has nothing to compete with these two trees.

The pavement ends at the Schulman Grove, but the unpaved 12-mile drive to the Patriarch Grove is navigable by all vehicles in dry conditions. Home to the Patriarch Tree, the world’s largest bristlecone pine, the Patriarch Grove is more primitive and much less visited than the Schulman Grove. Unlike the Schulman Grove, where I rarely stray far from the trail, I often find the most photogenic bristlecones here by venturing cross-country, over several small ridges east of the Patriarch Tree. Even without a trail, the sparse vegetation and hilly terrain provides enough vantage points that make getting lost difficult.

Clean air, few clouds, and very little light pollution make the bristlecone groves a premier night photography location. On moonless summer and early autumn nights, the bright center of the Milky Way is clearly visible from the slopes of the bristlecone forest. For the best Milky Way images, look for trees that can be photographed against the southern sky. And no matter how warm it is on 395 below, pack a jacket.

The bristlecone forest closes in winter.

Bishop area

An hour north of Lone Pine on 395 is Bishop. Its central location, combined with ample lodging, restaurant, and shopping options make Bishop an excellent hub for an Eastern Sierra trip—if you want to anchor in one spot and venture out to the other Eastern Sierra locations, Bishop is probably your best bet.

West of Bishop are many small but scenic lakes nestled in steep, creek-carved canyons that are lined with aspen (and some cottonwood) that turn brilliant yellow each fall. Many of these canyons can be accessed on paved roads, others via unpaved roads of varying navigability, and a few solely by foot.

Of these canyons, Bishop Creek Canyon is the best combination of accessible and scenic. To get there, drive west on Highway 168 (Line Street in Bishop). After about 15 miles you can decide whether to turn left on the road to South Lake, or continue straight to reach North Lake and Lake Sabrina (pronounced with a long “i”).

One of the area’s most popular sunrise spots, North Lake is a 1-mile signed detour on a narrow, steep, unpaved road—easily navigated in good conditions by all vehicles, but the un-railed, near vertical drop is not for the faint of heart. A mile or so beyond the turn to North Lake the road ends at Lake Sabrina, a fairly large reservoir in the shadow of rugged peaks and surrounded by beautiful aspen (but its bathtub ring when less than full is not for me).

South Lake is another aspen-lined reservoir that shrinks in late summer and autumn. Highlights on South Lake Road are a manmade but photogenic waterfall leaping from the mountainside, clearly visible on the left as you ascend, and Weir Lake, just before South Lake.

Both Bishop Canyon roads are worth exploring, especially in autumn, when the fall color can be spectacular. Each features scenic tarns and dense aspen stands accented by views of nearby Sierra peaks. Rather than beeline to a fall color spot, in autumn I drive the Sabrina and South Lake roads and pick the best color.

Highway 395 north of Bishop features a few of my favorite fall color destinations, including Rock Creek Canyon and McGee Creek. About a half hour north of Bishop, detour west off the highway to postcard-perfect Convict Lake. And just beyond the road to Convict Lake is the upscale resort town of Mammoth Lakes, just a few miles west of 395. The drive on 203 through Mammoth Lakes takes you past the Mammoth Mountain Ski slopes to Minaret Vista. This panoramic view of the sawtooth Minaret Range, Mt. Ritter, and Mt. Banner captures the essence of high Sierra beauty. From here, follow the road down the other side to see the basalt columns of Devil’s Postpile, and to take the short hike to Rainbow Fall.

Lee Vining area

Leaving Bishop, Highway 395 climbs steeply, crests near Crowley Lake, skirts the communities of Mammoth Lakes and June Lake, finally dropping down into the Mono Basin and Lee Vining. Though this is an easy, one-hour drive, you’ll feel like you’ve landed on a different planet. In October, detour onto the June Lake Loop, another popular fall color drive.

By far the most popular Mono Lake location is South Tufa, a garden of limestone tufa towers that line the shore and rise from the lake. Tufa are calcium carbonate protrusions formed by submerged springs and revealed when the lake drops. In addition to the striking tufa towers, South Tufa is on a point that protrudes into the lake, allowing photographers to compose with both tufa and lake in the frame while facing west, north, or east.

To visit South Tufa, turn east on Highway 120 about 5 miles south of Lee Vining. Follow this road for another 5 miles and turn left at the sign for South Tufa. Drive about a mile on an unpaved, dusty but easily navigated road to the large dirt parking lot. From here it’s an easy ¼ mile walk to the lake, but wear your mud shoes if you want to get close to the water. And don’t climb on the tufa.

While South Tufa can be really nice at sunset, mirror reflections on the frequently calm lake surface, and warm light skimming over the low eastern horizon, make this one of California’s premier sunrise locations. To get the most out of a sunrise shoot here, it’s a good idea to photograph South Tufa at sunset to familiarize yourself with the many possibilities here (and who knows, maybe you’ll get lucky and catch one of the Eastern Sierra’s spectacular sunsets).

In the morning, arrive at the lake at least 45 minutes before sunrise to ensure a good spot at this popular location—you can start shooting as soon as you arriving, using long exposures to brighten the scene and smooth the water. I usually start with scenes to the east, capturing tufa silhouettes against indigo sky and water. As the dawn brightens, keep your head on a swivel and be prepared to shift positions with the changing light.

As the sun approaches and the dynamic range increases in the east, I often turn to face west. Soon the highest Sierra peaks are colored with pink alpenglow, followed quickly by the day’s first direct sunlight. With the sun rising beneath the horizon behind me, its light slowly descends the Sierra peaks stretching before me. When the sunlight finally reaches lake level, for a few minutes the tufa towers are awash with warm sidelight, creating wonderful opportunities facing north. As with the Alabama Hills, without clouds to soften the sunlight and make the sky more interesting, the sunrise show is terminated quickly by contrasty light.

Other options in and near Lee Vining are the excellent Mono Lake visitor center on the north side of town, the small but very informative Mono Committee headquarters in the middle of town, any meal at the Whoa Nellie Deli in the Mobil Station (trust me on this), and Bodie, an extremely photogenic ghost town maintained in a state of arrested decay, less than an hour’s drive north. And a sinuous 20-minute drive west, up 120 (closed in winter) lands you at Tioga Pass, Yosemite’s east entrance and the gateway to Tuolumne Meadows.

Fall color in the Eastern Sierra

Each fall the Eastern Sierra becomes a Mecca for photographers chasing the vivid gold coloring the area’s ubiquitous aspen groves. The show starts in late September at the highest elevations, and continues well into October in some of the lower elevations. Fall color timing and locations vary from year-to-year, but the general fall color rule to follow here is: If the trees are still green, just keep climbing.

The best way to photograph the Eastern Sierra’s fall color is to explore: Pick a road that heads west and start climbing until something stops you. To give you a head start, here are a few of my favorite spots, from south to north. (Rather than beeline to specific locations in these ever-changing canyons, I’ve found it’s best to drive slowly and stay alert for opportunities along the way.)

Bishop Creek Canyon: Nice any season it’s open, Bishop Creek Canyon (detailed earlier) comes alive with gold each autumn. Aspen surrounding the canyon’s many lakes make for spectacular reflections. Of these, North Lake is probably the most popular, but autumn mornings can be extremely crowded here. The color in Bishop Creek Canyon usually peaks in late September at the highest elevations (near North Lake, Lake Sabrina, and South Lake), but lasts until mid-October farther down the canyon.

Rock Creek Canyon: Near the crest of the climb out of Bishop on 395, turn left at the sign for Rock Creek Lake. Climb this road along Rock Creek all the way up to its terminus at Mosquito Flat trailhead. Over 10,000 feet, this is the highest paved road in the Sierra. As with Bishop Creek Canyon, the best photography in Rock Creek Canyon is usually found at random points along the road—drive slowly and keep your eyes peeled.

McGee Creek: When you see Crowley Lake on the right, look for the road to McGee Creek on the left. This 2-mile unpaved road is navigable by all vehicles, but take it slow. It ends at a paved parking lot that’s the launching point for a hike up McGee Creek, into the canyon, and the mountains beyond. Unlike most other Eastern Sierra canyons, the dominant tree here is cottonwood. While I’ve had good success photographing along the creek right beside the parking lot, you can find nice color as far up the canyon as your schedule (and fitness) permits.

Convict Lake: The road to Convict Lake is just south of Mammoth Lakes. It’s a 2-mile paved drive to a beautiful lake nestled at the base of towering mountains—definitely worth the short detour off of 395.

June Lake Loop: Between Mammoth Lakes and Lee Vining is a 15 mile loop that exits 395 near the small town of June Lake (look for a gas station on the left) and returns to 395 a few miles down. Along the route you’ll find several lakes, and a waterfall at the very back of the loop (visible from the road).

Lundy Canyon: About 5 miles north of Lee Vining, turn left onto the Lundy Canyon road to enjoy one of my favorite Eastern Sierra fall color spots. The lower half of this road, below Lundy Lake, is often a good place to find late season color, but my favorite photo spots aren’t until road turns bad, just beyond the lake.

Driving slowly and with great care, most vehicles can make the 2 unpaved miles along Mill Creek to the end of the road. In addition to beautiful creek scenes, you’ll find several small, reflective beaver ponds along the way. If you make it to the end of the road, park and follow the trail up the canyon, through an aspen grove, for about ¼ mile to reach a small, waterfall-fed lake. The overgrown lakeshore makes photography here difficult, but a short walk along the shoreline to the left, toward the lake outlet, will take you to a massive beaver dam. Roll up your pants and get your feet (and more) wet for the best views of the lake.

Dunderberg Peak and Virginia Lakes: Shortly after the turn to Lundy Canyon, 395 climbs steeply to Conway Summit, at 8143 feet, the highest point on the entire route. On the left, just past a spectacular view of the entire Mono basin (worth the stop), is the road to Virginia Lakes. Here you’ll find some of the area’s earliest aspen to turn. Just beyond the Virginia Lakes road are colorful views of Dunderberg Peak and its aspen-blanketed slopes.