Some assembly required

Posted on February 10, 2014

Double Rainbow, Lipan Point, Grand Canyon

California Sunset, Sierra Foothills

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/5 second

32 mm

ISO 100

F14

Putting together material for the Grand Canyon Monsoon workshop that Don Smith and I do each August, I came across this image from the first shoot of our first workshop. With so many pictures in the two weeks we were there (for two workshops), and given the incredible events that followed, it’s amazing to me how well I remember the specifics of this early shoot (especially given how poorly I remember so many other things).

When Don and I pulled the group into Lipan Point that afternoon, a handful of puffy clouds floated overhead. But, as if on cue, within minutes of our arrival the clouds organized into a seething, dark gray tower; five minutes after that, a few drops fell—marble-size projectiles that landed with an audible splat at one- or two-second intervals. We ignored the rain and kept shooting, but when a lightning bolt struck a quarter mile away, we couldn’t get out of there quickly enough, retreating to the cars just as all hell broke loose. For the next we were assaulted with a pounding rain that obliterated the view and required shouting to be heard. As suddenly as it started, the rain stopped and the Canyon reappeared, bathed in sunlight. And with the sunlight came a full double rainbow. I mean, what could be more perfect, the Grand Canyon plus a rainbow? Unfortunately, from our vantage point on the rim, the rainbow beautifully framed nothing but sagebrush south of the canyon.

Understanding the physics of rainbows, I knew that there’s nothing random about their position—to get the rainbow above the canyon, I simply had to be on the other rim. With a choice between A: A four hour drive, and B: A twenty mile hike, I chose C: Get as far out into the canyon as the nearby terrain allows and hope for the best.

The “Point” part of Lipan Point refers to a rock protuberance that juts into the canyon. Scrambling onto the rock, I was able to change my angle of view enough to put the north-most end of the rainbow in the canyon before I ran out of point. Not the complete, rim-to-rim view I’d have liked, but at least something to work with. With the Grand Canyon as my background, a rainbow for the middle-ground, all I lacked was a foreground.

Scanning my surroundings, my eyes fell immediately on a group of shrubs side-lit by pristine, warm, late afternoon light. A horizontal composition would have given me too much foreground and too little rainbow, so I went vertical. At a focal length of 32mm, my depth of field app told me I could achieve the 8-foot hyperfocal distance I needed at f14. Spot metering on the brightest shrub, I dialed my shutter speed until the shrub was +2, and clicked.

These are a few of my favorite things

Posted on February 3, 2014

Maria von Trapp had them, you have them, I have them. They’re the favorite places, moments, and subjects that provide comfort or coax a smile no matter what life has dealt. Not only do these “favorite things” improve our mood, they’re the muse that drives our best photography. Mine include the translucent glow of a California poppy, a black sky sprinkled with stars, a breathtaking sunrise duplicated in reverse by still water, and the vivid arc of a rainbow following a cleansing rain. Also on my list (as you may have guessed by now) are the rolling hills and stately oaks of the Sierra foothills, a delicate slice of moon hovering above the horizon, and the subtle band of shifting color separating day and night.

I do my best to put myself in position to photograph all of these moments—the more I can combine, the better. For example, on my calendar each month (among other things) are the best days to photograph the old moon before sunrise, and the new moon after sunset. And in my GPS is a collection of foothill locations (though by now I’m sure my car could navigate to these spots on its own) with hilltop oak trees that stand against the sky.

The best evenings for the new moon in the most recent lunar cycle were Friday and Saturday, January 31 and February 1. With plans for Friday, I blocked Saturday and made the drive up to the foothills, where I waited at a favorite spot for the sun to drop and the moon to appear. Over the years I’ve accumulated lots of pictures of these trees beneath a variety of skies, with and without the moon. My composition decisions on each visit were mostly determined by the conditions: clouds, color, the moon’s direction, and the moon’s elevation above the horizon.

Saturday night’s cloudless, unspectacular sky spread a simple canvas that emphasized the crescent moon floating above the day/night transition I love so much. As an added bonus, Mercury joined the party, leading the moon to the horizon (above the tree on the right). In the deepening darkness I moved up and down the road to change the moon’s position relative to the trees. With the moon fairly high, I found that moderately wide, vertical compositions worked best. I underexposed slightly to and emphasize the trees’ shape with a silhouette; with nothing else to balance my frame, I decided on the symmetry of an isosceles triangle connecting the trees and moon.

Same view, different day

- Goodnight Moon, Sierra Foothills, California

- Oaks at Sunset, Sierra Foothills

- Crescent and Clouds, Sierra Foothills, California

- Red Sky, Oak at Sunset, Sierra Foothills

If you’re following the rules, you’re not being creative

Posted on January 28, 2014

What do you think would happen if I submitted this image a camera club photo competition? It might elicit a few oohs and ahhs at first, but I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t be long before somebody dismisses it because the primary subject is centered. And while “never center your subject” is standard camera-club advice for a beginner who automatically bullseyes every subject, reflexively reciting “Rules*” is a cop-out for faux critics who lack genuine insight. (Of course I’m not talking about you, I’m talking about that guy over there by the cookies.) Worse still, photographers who blindly follow Rules are leaning on a crutch that will only atrophy their creative muscles.

This is important

Rules are not inherently bad, but it should be the photographer controlling the Rules, not the other way around. In fact, if you’re following the Rules, you’re not being creative. One more time: If you’re following the Rules, you’re not being creative.

A couple of examples

One of the most oft-repeated Rules is the Rule of Thirds, which dictates that the primary subject be placed at the intersection points in an imaginary grid dividing the frame into horizontal and vertical thirds (think tic-tac-toe). Another RoT mandate is to never center the horizon, but to instead place it one third of the way up from the bottom or down from the top. Reasonable advice for people who like their images to look like everyone else’s, but it completely ignores the myriad reasons for doing otherwise.

For example, visual artists are often told to give their subjects more space in the frame in the direction they’re looking. In other words, if the subject is gazing rightward, place them on the left side of the frame so they’re looking across the frame and not directly into a virtual wall. But watching “12 Years a Slave” last weekend (one curse of being a photographer is the inability to turn off my internal critic) I noticed Solomon Northup longingly gazing directly into the left border of the frame, with a vast open sky behind him. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that this framing symbolized Northup’s physical and emotional confinement (but who doesn’t know someone who’d ding this framing at the photo club competition?).

And centering a subject is an effective creative tool. Photographing the Mono Lake South Tufa sunset above, I was thrilled to find the kind of mirror reflection usually reserved for sunrise at this often windy location. Enjoying softer light than I’d get shooting toward the sun at sunrise, I tried many compositions before settling on this absolutely symmetrical version to create an equilibrium that conveys the utter stillness I experienced that evening.

Shed the crutch and go forth

Rules serve a beginning photographer in much the way training wheels serve a five-year-old learning to ride a bike: They’re great for getting you started, but soon get in the way. As valuable as these support mechanisms are, you wouldn’t do Tour de France with training wheels, or the Boston Marathon on crutches.

In my workshops I’m frequently exposed to creative damage done to people rendered gun-shy by well-intended but misguided Rule enforcers. Camera clubs and photo competitions are great for many reasons, but I’d love to see them declared no-Rule zones. And if your group can’t no nuclear on Rules, how about at least adding a no-Rule (“best image that breaks a Rule”) competition or category to acknowledge that the Rules are not the final word?

My suggestion to everyone trying to improve their photography is to learn the Rules, but rather than simply memorizing them, do your best to understand their purpose, and how that purpose might conflict with your objective. Then, armed with that wisdom, each time you peer through your viewfinder, set the Rules aside and simply trust your creative instincts.

*Capitalized throughout to mock the deference they’re given

Come break the rules with me in a photo workshop

Eastern Sierra Photo Workshops

Asking for trouble at the camera club

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Returning to the scene of the crime

Posted on January 24, 2014

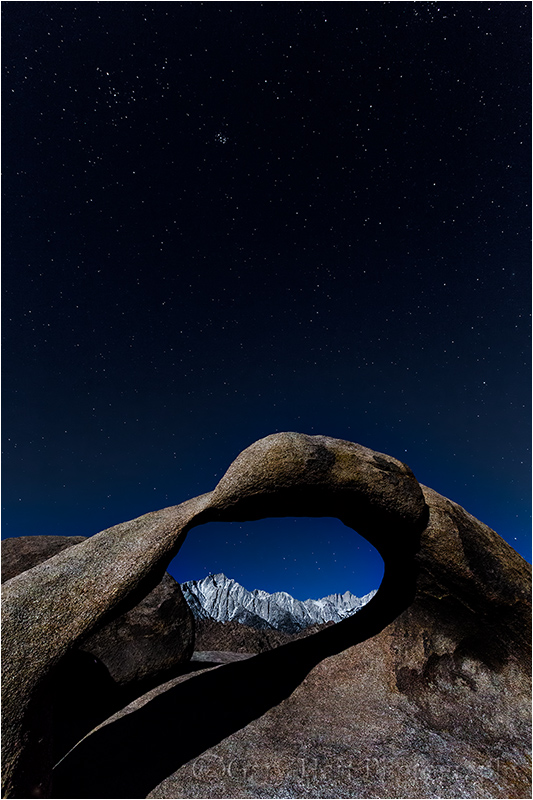

Moonlight, Whitney Arch, Alabama Hills, California

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

15 seconds

16 mm

ISO 3200

F8

* * *

Lone Pine Peak (12,944 feet) is on the left, Mt. Whitney (14,505 feet) is on the right. The small, dipper-shaped group of stars near the upper center is the Pleiades (a.k.a. the Seven Sisters) in Taurus, a cluster of new and still-forming stars about 400 light years distant.

Clueless. That’s one word that would describe my state the first time I attempted moonlight photography. It was about eight years ago, right here in the Alabama Hills. Though exposure and focus were more guesses than decisions, I ended up with a lucky shot of the Big Dipper suspended above moonlit granite boulders and an obsession was born.

The other thing I remember about that visit was thinking it would be really cool to photograph a full moon setting behind Mt. Whitney (the tallest point in the 48 contiguous United States). That thought got me researching moonrise/set data, and software that would allow me to plot the view angles. I ended up tapping the wealth of tables on the U.S. Naval Observatory website, which, among other things, returned the azimuth (the number of degrees east of due-north) of the moon for any time and location on Earth, and the moon’s altitude (degrees above the flat horizon) at any specified time. Then I stumbled upon a tool in National Geographic Topo! software that allowed me to plot the azimuth and align my photo spot with my subject: I just pick my base point (the location from which I want to photograph) and click on a point on the map at the moon’s azimuth at the time I want to photograph it. The software conveniently draws a line connecting the two points—anything on the line aligns with the moon. Pretty cool (at least at the time—today there are tons of apps that make this much simpler).

Early one morning the following August, armed with ultimate confidence in my new-found knowledge, I embarked on a six hour drive to the Alabama Hills. My goals were two-fold: In addition to a sunrise moonset behind Mt. Whitney, I wanted to photograph the Whitney Arch by moonlight. I arrived late that afternoon, scouted a bit, photographed a rather boring sunset, then traipsed out to the arch in the dark (this was in the days before the trail that guides visitors right to it), about a quarter mile from the parking area, for a moonlight shoot. My continued cluelessness about moonlight photography was exacerbated this time by the fact that, following the lucky shot of my previous visit, I no longer knew I was clueless.

I had fun photographing in the perfect silence of absolute solitude, spent the night in the back of my truck, and woke to find the moon exactly where I’d plotted it. Phew. It turned out that my moonlight image from the previous night was okay, but the years have made me more aware of its flaws: Because focusing on the Sierra Crest was much easier than focusing on the arch, I ended up with just a little more foreground softness than I like. And my exposure was a little darker than ideal. (Flaws that become more apparent the larger the image.) For years I’ve wanted a do-over, and while I’ve been back many times, until last week circumstances have always prevented me from getting out to the arch in moonlight.

There’s really only room at the arch for three or four photographers to comfortably photograph Mt. Whitney through the opening. And when leading a workshop, my priority isn’t my own photography (one of the reasons I haven’t been able to manage a do-over). But this time only couple of others in my group decided to try their hand at the arch, so I squeezed in and clicked a few frames. I started horizontal, but quickly switched to vertical to maximize the sky (and eliminate a photographer on my left) and soon found a composition that worked. Drawing from experience, this time I focused on the arch, targeting the most distant moonlit spot in my frame. Focus, while difficult, was much easier than my first attempt as I found live-view magnified five times was just clear enough that I was pretty sure I’d found focus (10X was too muddled). But to be certain, I checked the resulting frame, magnified on my LCD, to verify. While the arch was indeed sharp, Whitney was slightly soft at f4, so I stopped down to f8 and bumped my ISO up to 3200. Bingo.

The cure for blue skies

Posted on January 20, 2014

Sunrise Moonset, Sierra Crest, Alabama Hills, California

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/8 second

29 mm

ISO 200

F11

* * *

The prominent mountain on the left is 12,944 foot Lone Pine Peak. At 14,495 feet, Mt. Whitney is the highest point in the 48 contiguous United States; it’s the shark-tooth peak left of center. The slightly concave mountain on the far right is 14,380 foot Mt. Williamson.

A good landscape image usually involves, well…, a good landscape. But that’s only half the equation—photographers also need photogenic conditions—soft light, interesting skies, dramatic weather, or anything else that elevates the scene to something special. While we have absolute control over the time and location of our photo outings, the conditions have a significant random (luck) component.

Despite being less than a day’s drive from many of the most treasured photo destinations in the world, most of my photo trips are planned months in advance. Workshops in particular require at least a year of advance planning on my part, and many months of schedule adjustment and travel arrangements for the participants. I think I’ve pretty much established that positive thinking, finger crossing, divine pleas, and ritual incantation (no virgin sacrifice yet) are of zero value where photography is concerned—sometimes conditions work out wonderfully, sometimes not so much. And while I’ve photographed my workshop locations many times, I know most of my workshop participants haven’t, which is why I do my best to schedule my workshops when the odds are best for interesting skies.

My annual Death Valley / Mt. Whitney photo workshop is a perfect example: Among the driest places on Earth, Death Valley gets only about an inch of rain each year and suffers from chronic blue skies. Ever the optimist, I schedule my DV/Whitney workshop from mid-January through early February, when the odds, though still low, are at least best for clouds. And while I’ve actually been pretty lucky with the clouds in past workshops, to hedge my bets further, I always schedule this workshop to coincide with a full moon—if we don’t get clouds, the moon always seems to save the day (and night).

This year’s DV/Whitney workshop wrapped up Saturday morning. Unfortunately, it landed in the midst of what is on its way to becoming an unprecedented drought in California. After two dry winters, this winter is worse—a persistent high pressure system has set up camp above California, creating an impenetrable force field that deflects clouds and and bathes the state weather that is absolutely beautiful for everything but photography. In this year’s DV/Whitney workshop’s four+ days, we enjoyed highs in the glorious 80s, and I don’t recall seeing a single cloud (though there were unconfirmed rumors of a cloud sighting on the distant horizon late in the workshop).

But cloudless skies don’t need to mean lousy photography—they just shrink the window of opportunity. Places like Mosaic Canyon and Artist’s Palette are nice in the early morning or late afternoon shade. And in general, when clouds aren’t in the picture, the best photography skies are on the horizon opposite the sun before sunrise and after sunset. Last week I made a point of getting my group on location at least 45 minutes before sunrise, and kept them out well past sunset to photograph Death Valley’s one-of-a-kind topography beneath twilight’s shadowless pink and blue pastels. Among other things, in this light the dunes were fantastic (I was able to find a relatively footprint free area) all the way from shadowless twilight through high contrast early morning light, and the first light on Telescope Peak from Badwater was wonderful.

But the workshop’s real highlight, the element that elevated our week into something special, was the moon. The real moon show didn’t begin until it showed up above the primary views on our final two sunrises, but we got a nice preview on our first sunset when the waxing gibbous disk rose into the twilight wedge above the mountains east of Hell’s Gate. The next evening I took the group to panoramic Dante’s View; while the prime objective was photographing Death Valley’s last light and the sun setting from 5,000 vertical feet above Badwater, I instructed everyone to walk across the parking lot after sunset to catch the nearly full moon rising above the equally expansive (though significantly less spectacular) panorama of distant peaks to the east. The moon arrived early enough to allow at least ten minutes of quality photography, then we just kind of hung out to watch it for a little while longer. Very nice.

Friday morning’s sunrise we found the moon glowing as promised in the predawn indigo above Zabriskie Point. As the morning brightened, we watched the nearly round disk slide through twilight’s throbbing pink before disappearing directly behind Manly Beacon just a few minutes after sunrise.

But as nice as the Zabriskie shoot was, I think my personal favorite was the workshop’s final sunrise from the Alabama Hills. The group, now expert at managing the difficult contrast between foreground shadows and brilliant moon, immediately spread out to find their own foreground. One or two headed straight for the Whitney Arch (aka, Mobius Arch), while the rest of us were quite content with the variety of boulders west and south of our the arch.

The thing that makes the Alabama Hills such a special location for sunrise is its position between towering peaks to the west, and relatively flat horizon to the east. At sunrise here, the Sierra crest juts into the blue and rose of the Earth’s receding shadow, then transitions to amber when the first rays of sunlight kiss its serrated peaks. You anticipate watch the sun’s arrival by watch the shadow descent the vertical granite until it bathes the weathered boulders with warm, ephemeral sunlight. Then, just like that, the show’s over.

I’ve shot this scene at sunrise so many times that I usually remain a spectator unless something special moves me to pull out my camera. Last Saturday, despite the absence of clouds, I just couldn’t resist the pull of the moon, which hovered like a mylar balloon in the night/day transition. At first there wasn’t enough light to photograph detail in the rocks and moon in a single frame, but eventually, with the help of a two-stop graduated neutral density filter, I was able to capture the image at the top of the blog.

Orion, Badwater by Moonlight, Death Valley

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

15 seconds

17 mm

ISO 1600

F4

* * *

Another great thing about timing the Death Valley workshop to coincide with a full moon is our moonlight shoots. Of all the workshop moonlight shoots I do throughout the year, I think I look forward to the Death Valley Badwater shoot the most. This year’s didn’t disappoint—not only was the photography great, there’s just something about the playa’s warm temperatures and utter stillness that creates a genuinely festive atmosphere.

Moonset, Mt. Whitney and the Alabama Hills, California

* * *

Last year I photographed the same scene in different conditions. While this year’s capture highlights the Sierra crest and uses the blank sky and dark foreground to create a twilight feel, last year’s image was captured shortly after the sun lit the peaks and colored the clouds. I used a tighter composition to emphasize Mt. Whitney, the moon, and the pink clouds.

Stupid cold

Posted on January 12, 2014

We warm blooded humans have lots of ways to express the discomfort induced by low temperatures, ranging from brisk to chilly to freezing to frigid. But because I’ve always felt that we need something beyond frigid, something that adequately conveys the potential suffering, let me submit: stupid cold. At the risk of stating the obvious, “stupid cold” is when it’s so cold, the only people without a good reason to be outside (for example, the house is on fire) are, well….

Before I get into a recent personal encounter with stupid cold, let me offer a little background. Being California born and raised, I often find myself with a slightly higher cold threshold than many of my workshop participants. I’m not proud to say that pretty much when the temperature drops below 50, I’m breaking out the gloves and down jacket. Without shame. I get a lot of grief for this, but that’s fine because I’m comfortable. In fact, no matter how cold it gets in California, I’ve always been able to bundle up enough to stay comfortable. Viva la Mediterranean climate.

So imagine my chagrin when, while preparing for my recent trip to Bryce Canyon to co-lead Don Smith’s Bryce/Zion workshop, I saw overnight lows in the single digits (!) forecast. I know many people live places that get this cold, but how many of them actually go out specifically at the time when it’s coldest (sunrise)—and then just stand there? Unfortunately, when you’re a photographer, especially a photographer who is counted on by paying customers, staying in bed at sunrise is not an option.

So anyway, single digit lows. Surely, I rationalized, anyone who can endure night games at Candlestick Park in July, can, given enough layers, handle whatever Bryce can dish out. So, employing my tried and true Candlestick Park infinite layer approach, I sucked it up, cleared my closet of all cold weather gear, crammed it into my largest suitcase, then crossed my fingers when the Southwest ticket agent hefted the bulging cube onto the scale (49.8 pounds, thankyouverymuch). Off to Bryce.

So whatever happened to those days when the weather forecast was a crap-shoot, when you never really worried about the forecast too much because it was rarely right? We arrived at Bryce to find temperatures as cold as advertised. Windy too. And as if to rub salt in the wound, the coldest shoot we had was the workshop’s first sunrise, before anyone had a chance to acclimate: 10 degrees fahrenheit and 25 MPH winds (I know, I know, that’s nothing compared to your January Yellowstone bison shoot, or that time in Saskatchewan when you stayed up all night to photograph the northern lights, but you can’t say anything unless you sat through the last pitch of a night game at Candlestick Park).

I must say, my Candlestick more-is-better strategy almost worked. Two pairs of wool socks inside sub-zero rated boots kept my toes nice and toasty for the duration. Silk long-johns, flannel-lined jeans, insulated over-pants—my legs were happy too. And my torso did quite well inside a long sleeve wool undershirt, Pendleton (wool) shirt, Patagonia down shirt, and a down jacket. My ears were cold but tolerable beneath a wind-stop ear band and cozy wool cap. And my nose, cheeks, and mouth were a bit more exposed, but a wool gator took enough of the edge off to make it manageable.

But, despite all the preparation, what thirty years of Candlestick experience hadn’t prepared me for was cold hands. Oh. My. God. I thought I was ready with my thin poly running gloves as liners for thick wool gloves—not even close. The problem was, unless you’re keeping score, watching a baseball game doesn’t require hands unless there’s something to cheer for (a rare event for most of my Candlestick years)—at the ‘Stick I could sit on my (gloved) hands, bury them in pockets or beneath my wool blanket (never left home without one), or all of the above. But a camera, it turns out, requires hands. Fingers too. I quicky found that I could compose and click maybe three frames before the cold drove me to the nearby visitor’s shelter to pound life back into my fingers. Not a productive morning.

After this first sunrise, things improved. Temperatures warmed a bit, the wind abated, my body adjusted (slightly), and I was able to mitigate my hand problem with the purchase of silk liner gloves and thicker wool gloves. I also came away with a new found appreciation of my Hawaii workshops—sunrises in a tank-top, shorts, and flip-flops. Nothing stupid about that.

Compared to the cold we’d experienced at sunrise, at 20 degrees, the afternoon I took this picture was downright balmy. When we arrived at Sunrise Point, the snow that had been falling most of the afternoon was still falling, obscuring the view to the point where many in the group retreated to the car. But those of us who stayed out were treated to a twenty minute window between the lifting of the clouds and the fall of darkness. Not the spectacular color and warm light that generates so much excitement, but wonderful, even light that really allowed the pristine snow to stand out against the red sandstone.

Securing the border

Posted on January 8, 2014

If you’ve ever been in one of my workshops, or (endured) one of my image reviews, you know where I’m going with this (I can sense eyes rolling from here). But I hope the rest of you stick with me, because as much as we try be vigilant, sometimes the emotion of a scene overwhelms our compositional good sense—we see something that moves us, point our camera at it, and click without a lot of thought. While this approach may indeed capture the scene well enough to revive memories or even impress friends, you probably haven’t gotten the most out of it. So before every click, I do a little “border patrol,” a simple mnemonic that reminds me to deal with small distractions on the perimeter that can have a disproportionately large impact on the entire image. (I’d love to say that I coined the term in this context, but I think I got it from Brenda Tharp—not sure where Brenda picked it up.)

To understand the importance of securing your borders, it’s important to understand that our goal as photographers is to create an image that invites viewers to enter, and persuades them to stay. And the surest way to keep viewers in your image is to help them forget the world beyond the frame. Lots of factors go into crafting an inviting, persuasive image—things like balance, visual motion, and relationships are essential (topics for another day), but nothing reminds a viewer of the world beyond the frame faster than objects jutting in or cut off at the edge, or visually “heavy” (large or bright) objects that pull the eye away from the primary scene. To avoid these distractions, for years I’ve been practicing, and advocating, border patrol before clicking. Just run your eyes around the perimeter, note everything that’s on or near the border, and ask yourself if that really is the best place for the edge of the frame.

Sometimes border patrol is easy—a simple scene with just a small handful of objects to organize, all conveniently grouped toward the center, usually requires very little border management. But more often than not we’re dealing with complex scenes containing multiple objects scattered throughout and beyond the frame: leaves, rocks, clouds, whatever, with no obvious demarcation.

Incoming Storm, Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley

Border patrol for this image was relatively simple—with nothing prominent near the edges, I was primarily concerned about visual balance, though I did conduct a bit of border patrol on the sky to ensure that I chose the best place to break the churning (rapidly moving) clouds.

The frigid Yosemite scene at the top of his post was as difficult as it was beautiful. With my camera in live-view mode atop my tripod, I relatively quickly came up with a composition that encompassed the beauty and felt fairly balanced, but all the snow-capped rocks, patches of ice, and randomly distributed hoarfrost made it pretty much impossible to find the perfect place for my border.

The circle of five snow-covered rocks in the left foreground was my foreground anchor—I needed to give these rocks space, and to balance them with the field of hoarfrost blooms in the right foreground. I was very aware of the rocks cut off in the left and right middle-ground, but going any wider introduced all kinds of new problems (just outside the current frame) at the bottom and on both sides. On the other hand, a tighter composition would have cut off the ice-etched trees that stood out so beautifully against the shaded evergreen background. Sigh. So, I did what every photographer must do in virtually every image: compromise. Compromise in this case meant opting for the lesser of multiple evils, hopeful that the unique drama of this frigid scene would be enough to overcome its flaws.

What flaws? I thought (hoped) you’d never ask. After several minutes of shifting up/down, left/right, forward/backward (while crossing my fingers that the ice on which I was stationed would hold out), and zooming in and out, I managed to get all of my icy trees at the top of the frame and find a relatively clean patch of water in front of me for the bottom of the frame. The large rock cut off on the middle right doesn’t bother me too much either—large objects cut in the middle can serve as frames that hold the eye in the scene. But if I could have had complete creative control over this scene (this is where painters have a distinct advantage), I’d have done something about those small rocks cut off on the middle left—I know nobody would be consciously aware of them, but there’s nothing like a clean border to hold a viewer in the scene, and those rocks just aren’t clean to my eye.

Because you can actually practice border patrol, and composition in general, in the comfort of your home, another frequent theme in my image reviews is the value of the crop tool as a learning device. Pick any image—yours or someone else’s—and see how many compositions you can find in it. The goal isn’t to create usable images (you’ll loose too many pixels for that), it’s to train your eye to see things you currently miss in the field. I promise that if you do this enough, you’ll find yourself naturally seeing compositions and fixing obvious problems before you click.

Looking back at 2013, and ahead to 2014

Posted on January 1, 2014

Three Strikes, Bright Angel Point, North Rim, Grand Canyon

This is a single, 1/3 second click that managed capture three simultaneous lightning strikes. Set up on a tripod, I’d composed to balance the frame between the rainbow and the area receiving the most strikes. Rather than try to manually react when I saw a lighting flash, I let my Lightning Trigger detect the lightning and click for me. I got many one and two bolt frames, but this is the only frame that captured three.

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/3 second

F/11

ISO 100

24-105 f4L lens

While I’ve been taking a little Holiday break from my blog, I have spent some of my non-family time reviewing my 2013 images. Given the number of trips I take, and images I click, it always amazes me how well I remember every detail of my favorites—who I was with and what the circumstances were, not to mention composition and exposure decisions that are still as clear in my memory as the day I took the picture. I’m guessing it’s that way for other photographers too, because I’m convinced that our best photography comes when we concentrate on those things that move us emotionally. For example, since I’ve always been something of a weather geek, it stands to reason that several of my favorites feature active weather. And another lifetime passion is astronomy, and while I didn’t consciously bias this year’s selections toward the celestial, that sure seems to be how it worked out.

I have lots of great stuff planned for 2014: my regular annual workshops in Death Valley, Yosemite, Hawaii, the Eastern Sierra; my second annual Grand Canyon monsoon workshop with Don Smith; a raft trip down the Grand Canyon in May (bucket list item). And on any photo trip, whether it’s a workshop or a personal trip, I research and plan to make sure the odds for something special are as high as they can be, but it’s usually the unexpected moments that thrill me most—those times when I set out with one intention and found something else, or was disappointed when weather or other conditions beyond my control derailed the original plan.

Case in point: I scheduled an entire workshop around Comet ISON, and while ISON fizzled, if I hadn’t been in Yosemite to photograph it, I never would have witnessed Valley View, decked out in ice, glistening in the light of a full moon. Or the Maui workshop, scheduled before I had any idea of Comet PanSTARRS, that just happened to coincide with the comet’s post-perihelion conjunction with the new moon. But the one that thrill me most was the above sunrise at the Grand Canyon, the final morning of our second workshop—Don and I were going to start the thirteen hour drive home later that morning, and others in the group had flights to rush off to. Given the bland weather forecast, it would have been easy to blow off the shoot and let everyone sleep in. But we got up in the cold and dark, all of us, and were treated to a two hour electric show that started in blackness and culminated with a rainbow as the sun peeked above the canyon’s east rim.

So, without further adieu, and in no particular order, here are my current 2013 favorites (click a thumbnail for a larger version with more info, and to start the slide show):

- Moonlight Cathedral, Valley View, Yosemite

- Poppy Pastel, Sierra Foothills, California

- Facing West, Molokai from West Maui, Hawaii

- Comet PanSTARRS and New Moon, Haleakala, Maui

- Night Lightning, Roosevelt Point, Grand Canyon North Rim

- Milky Way and Halemaʻumaʻu Crater, Kilauea, Hawaii

- Winter Reflection, Half Dome and the Merced River, Yosemite

- Color and Light, Bright Angel Point, Grand Canyon

- Autumn Snow, Valley View, Yosemite

- Night and Day, Crescent Moon Rising Above Mono Lake

- Incoming Storm, Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley

- Three Strikes, Bright Angel Point, Grand Canyon

- Before Sunrise, South Tufa, Mono Lake

- White-Out, Cook’s Meadow, Yosemite

- Crescent Moon and Oaks at Dusk, Sierra Foothills, California

- Leaf, Bridalveil Creek, Yosemite

Two out of three ain’t bad

Posted on December 20, 2013

Moonlight Cathedral, El Capitan, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

30 seconds

23 mm

ISO 1600

F8

I scheduled my Yosemite Comet ISON photo workshop way back when astronomers were crossing their fingers and whispering “Comet of the Century.” Sadly, the media took those whispers and amplified them a thousand times—when ISON did its Icarus act on Thanksgiving day, its story became the next in a long line of comet failures (raise your hand if you remember Kohoutek).

But anyone who understands the fickle nature of comets would be foolish to get too excited about (or plan an event solely around) a comet’s promised appearance. So I scheduled this workshop knowing that even if the comet fizzled, storms and snowfall can make winter in Yosemite Valley spectacular. But, because snowfall in Yosemite is also far from a sure thing, to further enhance our chances for something special, in addition to Comet ISON and winter conditions, I scheduled this workshop to coincide with the December full moon. And while we didn’t get the comet, well, to quote Meat Loaf, “two out of three ain’t bad.”

Yosemite Valley received nearly a foot of snow a few days before the workshop started. Given Yosemite frequent sunshine and relatively warm temps, normally that snow would have all but disappeared from the trees and rocks within a few hours, and within a couple of days would have been marred by large brown patches—exactly what happened in the unshaded parts of Yosemite Valley. But because this storm was followed immediately by a cold snap, those parts of the valley that remained all day in the shade of Yosemite’s towering, sheer granite walls (mostly the south and/or west side of the valley) didn’t shed their snow and actually accumulated ice as the week went on.

Valley View was the prime beneficiary of this all day shade—by the time my workshop started, snow-capped rocks, hoarfrost blooms, and a sheet of windowed ice had elevated this always beautiful location to more beautiful than I’ve ever seen it. Full moon notwithstanding, it was the highlight of the workshop. Taking advantage of our unique opportunity, my group photographed Valley View early morning, late afternoon, at sunset, and (as you can see) by moonlight.

There are lots of things human vision can do that the camera can’t—fortunately, one of those things is not see in low light. While moonlight adds beauty to any scene, when a scene starts out off-the-charts-beautiful, moonlight makes it a downright spiritual experience. Though moonlight is beautiful to the eye, even at its brightest, a full moon isn’t bright enough to reveal all the beauty present. Enter the camera.

Giving this scene lots of light allowed me to reveal how it would appear if your eyes could take in as much light as, say, an owl. Or your cat. The blueness of the sky, the sparkling ice crystals, the reflection in the river—that beauty is no less real just because it’s invisible to our eyes.

To reveal all this “invisible” beauty, I started at ISO 800, f4, 15 seconds. But the unusually extreme (for moonlight photography) depth of field this composition required caused me to increase to ISO 1600 and 30 seconds to allow the extra DOF f8 provides. And I was thrilled to discover that there was enough light to enable live-view manual focus (my now preferred focus method for all situations). According to my DOF app, focusing about eight feet into the frame would give me sharpness from front-to-back, but just to be sure, after capture I magnified image in my LCD and checked the ice in the foreground and trees atop El Capitan.

The other problem I needed to deal with was lens flare, an easy thing to forget about when photographing in the dark. But the moon is a bright light source and all the lens flare rules that apply to sunlight photography also apply to moonlight—if moonlight strikes your front lens element, you’ll get lens flare. Since I hate lens hoods, I manually shield my lenses in flare situations. A hat works nicely, but there was no way I was taking my snuggly warm hat off, so I shaded my lens with my hand for the entire 30 seconds of my exposure.

BTW, see that bright light shining through the tree at the base of El Capitan? That’s Jupiter.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints

A Gallery of Snow and Ice

Click an image for a closer look and slide show. Refresh the window to reorder the display.

Oops

Posted on December 17, 2013

Winter Moonrise, Merced River, Yosemite

Canon EOS 5D Mark III

1/10 second

40mm

ISO 800

F16

Last Friday evening, this professional photographer I know spent several hours photographing an assortment of beautiful Yosemite winter scenes at ISO 800. Apparently, he had increased his ISO earlier in the day while photographing a macro scene with three extension tubes—needing a faster shutter speed to freeze his subject in a light breeze, he’d bumped his ISO to 800. Wise decision. But, rushing to escape to the warmth of his car, rather than reset the camera to his default ISO 100 the instant he finished shooting, he packed up his camera with a personal promise to adjust it later, when his fingers were warmer—surely, he rationalized, removing the extension tubes and macro lens would remind him to reset the ISO too. (You’d think.) But, despite shutter speeds nowhere near what they should have been given the light and f-stop, he just kept shooting beautiful scene after beautiful scene, as happy as if he had a brain.

I happen to know for a fact that this very same photographer has done other stupid things. Let’s see…. There was that time, while chasing a sunset at Mono Lake, that he drove his truck into a creek and had to be towed out. And the two (two!) times he left his $8,000 camera beside the road as he motored off to the next spot. And you should see his collection of out-of-focus finger and thumb close-ups (a side effect of hand-holding his graduated neutral density filters). Of course this photographer’s identity isn’t important—what is important is dispelling the myth that professional photographers aren’t immune to amateur mistakes.

And on a completely unrelated note…

Let’s take a look at this image from, coincidentally, last Friday evening. Also completely coincidentally, it too was photographed at ISO 800 (go figure)—not because I made a mistake (after all, I am a trained professional), but, uhhh, but because I think there are just too many low noise Yosemite images. So anyway….

This was night-two of what was originally my Yosemite ISON workshop—but, after the unfortunate demise of Comet ISON and a week of frigid temperatures in Yosemite, became my Yosemite ice-on workshop. That’s because, to the delight of the workshop students (and the immense relief of their leader), much of the one foot of snow that had fallen the Saturday before the workshop’s Thursday start had been frozen into a state of suspended animation by a week of temperatures in the teens and low-twenties.

Each day we rose to find nearly every shaded surface in Yosemite sheathed in a white veneer of snow and ice. (Valley locations that received any sunlight were largely brown and bare.) And the Merced River, particularly low and slow following two years of drought, was covered in ice in an assortment of textures and shapes from frosted glass to blooming flowers. Adding to all this terrestrial beauty was a waxing moon, nearly full, ascending our otherwise boring blue skies and illuminating our nightscapes.

On Friday night I guided my group to this spot just downstream from Leidig Meadow. There we found the moon, still several days from full, glowing high above the valley floor, and Half Dome reflected by a watery window in the ice. I captured many versions of this scene, from tight isolations of the reflections to wide renderings of the entire display. It’s too soon to say which I like best, but I’m starting with this one because it most clearly conveys what we saw that evening.

I chose a vertical composition because including the moon in a horizontal frame would have shrunk Half Dome and the moon, and introduced elements on the right and left that weren’t as strong as Half Dome, its reflection, and the snowy Merced River. (Sentinel Rock is just out of the frame on the right—as striking as it is, I wanted to make this image all about Half Dome.)

My f16 choice was to ensure sharpness throughout the frame, from the ice flowers blooming in the foreground, to Half Dome and its reflection. As you may or may not know, the focus point for a reflection is the focus point of the reflective subject, not the reflective surface. That means when photographing a reflection surrounded by leaves, ice, rocks, or whatever, you need to ensure adequate DOF or risk having either the reflection or its surrounding elements out of focus. Here I probably could have gotten away with f11, but my iPhone and its DOF app were buried beneath several layers of clothes, and using it would have require removing two pair of gloves.

I’d love to say that I chose ISO 800 to freeze the rapids, but I’m not sure you’d buy it. So I’m sticking with my too many low noise Yosemite images story and moving on. (A few cameras ago, ISO 800 would have meant death to this image, but today, thankfully, it’s mostly just a lesson in humility.)

A Yosemite Winter Gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.