Eloquent Images by Gary Hart

Insight, information, and inspiration for the inquisitive nature photographer

A Horsetail of a different color

Posted on February 22, 2016

Horsetail Fall Rainbow, El Capitan, Yosemite

Sony a7R II

Tamron 150-600 (Canon-mount with Metabones IV adapter)

1/250 second

F/8

ISO 125

I just returned from my 2016 Yosemite Horsetail Fall photo workshop. I’ve the photographed the midday light shafts at Upper Antelope Canyon, Schwabacher Landing at sunrise, Mesa Arch at sunrise, winter sunset at Pfeiffer Arch, and Horsetail fall each February for over ten years. But nothing compares to the mayhem I witnessed this weekend at Horsetail Fall. Not even close. I’ll be writing more about the experience soon, but right now the only words I have are: Oh. My. God.

But anyway…

About an inch of snow fell the night before my workshop’s 1:30 p.m. Thursday start. Because the storm was clearing and the snow was melting fast, I postponed the orientation that always precedes each workshop’s first shoot and, following quick introductions, hustled the group straight out to photograph what would likely be the best conditions of the workshop.

Our first stop was Tunnel View, and it didn’t disappoint. I rarely get my camera out at Tunnel View unless I can get something truly special, and I had no plan to that afternoon. But the storm had rejuvenated Horsetail Fall enough to make it clearly visible, a rare treat from that distance, and I decided to click a couple of frames.

Extracting my a7RII, I attached my Tamron 150-600 lens and targeted the fall, clicking a few images of the fall amidst shifting clouds. When the clouds opened enough to illuminate El Capitan, I did a double-take when splashes of red, yellow, and violet appeared in Horsetail’s wind-whipped mist.

After alerting my group to the rainbow, I zoomed all the way to 600mm and snapped a few vertical images of my own. With the wind tossing the spray, each image was a little different from the one preceding it. As I clicked this frame, an ephemeral spiral of wind spread the mist, making it the most colorful of the group.

As the sun dropped behind us, the rainbow climbed the fall and finally disappeared. Soon another rainbow appeared, this one at the base of Bridalveil Fall across the valley. We stayed long enough to photograph that rainbow, then headed out for what turned out to be a very successful, more classic Horsetail sunset shoot. Our Horsetail success that night allowed us to concentrate on other Yosemite subjects the rest of the week, while thousands of Horsetail Fall aspirants jockeyed for parking and a clear view through the trees.

Stay tuned for more about the Horsetail Fall experience, which has now officially achieved ridiculous status.

Let me help you photograph Horsetail Fall next February

~ ~ ~

Or, (if you’re brave) you could do it yourself

Ten Years of Horsetail Fall Images

(Look closely at the horizontal, “Twilight Mist” image to see Horsetail’s location)

Category: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, rainbow, Sony a7R II, Tamron 150-600, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, Horsetail Fall, nature photography, Photography, Rainbow, Yosemite

Don’t settle for the trophy shot

Posted on February 14, 2016

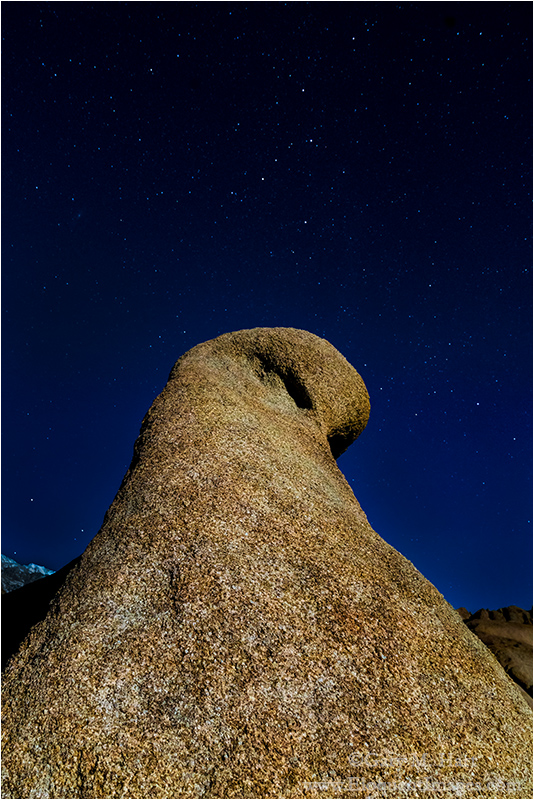

Cassiopeia Above Mobius Arch, Alabama Hills, California

Sony a7R II

Sony/Zeiss 24-70 f4

20 seconds

F/8

ISO 3200

Trophy shot: A beautifully executed capture of a frequently photographed scene.

In Monday’s post I wrote about relationships in nature. They really are everywhere, these juxtapositions of landscape, light, and sky that we photograph by virtue of our timing, position, and creative vision. In their pursuit, photographers label photo spots a “sunrise location” or “sunset location,” research the best time to photograph pretty much every popular landmark, plot the when and where of the moonrise, and…, well, you get the idea.

Unfortunately, in this age of ubiquitous cameras and limitless information, these easy relationship images have become cliché, a “trophy” to display in what seems to be a never-ending “top-this” cycle. While putting a beautiful scene with good light or a vivid sky makes a great foundation for a nice image, elevating an image above trophy status requires a serious infusion of creativity. In other words, rather than settle for an image that’s merely a flawlessly executed version of the same scene we’ve all seen hundreds of times, photographers should be seeking unique relationships between the scene’s varied elements, relationships that look deeper than the conventional treatment.

For example

(Like many other photographers) I’ve photographed California’s Alabama Hills a lot. Here stacked, weathered granite boulders provide a dramatic foreground for Mt. Whitney and the precipitous eastern escarpment of the Sierra Nevada range.

Despite an almost infinite variety of potential foreground subjects, the Alabama Hills trophy shot is Mobius Arch (aka, Whitney Arch), which makes a striking frame for Mt. Whitney. Some version of this composition has been a prime goal for many photographers, but like most easy captures these days, there’s rarely anything special about Mobius Arch images.

As with any location, it helps to start with a nice sky and good light. The natural relationships I try to add to the Alabama Hills’ beauty include sunrise alpenglow on Mt. Whitney, warm light on the granite boulders, and the moon’s disappearance behind the serrated, snow-capped peaks. But as beautiful as these phenomena are, they’re still not enough to set one Mobius Arch image apart from the other.

Moonset, Mt. Whitney and Mobius Arch, Alabama Hills, California

As a workshop leader I have to take my groups to the arch because if they’ve never been here before, it’s probably what they came to see. But my job doesn’t end there—it’s also incumbent on me to help my students find alternate compositions that use the arch in a unique way, or don’t use the arch at all.

I encourage Alabama Hills first-timers to seek relationships that combine the foreground rocks, distant peaks, and whatever is happening in the sky in ways they haven’t seen before. It can take a while, but the longer they work on a scene, the more the hidden relationships start to appear. Eventually most tire of the arch and start wandering off to explore the countless other opportunities nearby.

About this image

Arch or not, a particular Alabama Hills favorite of mine is moonlight, especially in winter, when the snowy crest glows with reflected moonlight. Last month, after three wonderfully cloudy days in Death Valley, my Death Valley workshop group traveled to Lone Pine to wrap up the workshop with a sunset and sunrise in the Alabama Hills. Since our Death Valley moonlight shoot had been preempted, after dinner in Lone Pine I took everyone up to the Mobius Arch area to give moonlight one more try.

The sky that night cooperated wonderfully. I started by bouncing between photographers making sure they’d mastered the exposure and focus challenges of moonlight photography. It wasn’t long before everyone was up to speed (it’s not hard) and scattering in search of their own moonlight boulder, mountain, and sky relationships.

Leading a group doesn’t allow me to do creative photography and natural relationship hunting, but that night I did find a couple of minutes to photograph some favorite compositions in the moonlight. It’s amazing how easily the eyes adjust to moonlight, and soon found myself composing as if we were shooting in daylight. It was also quite cold on this January night, but it’s amazing how easily the cold is ignored when the photography’s good.

When the cold started to trump the photography, I walked out to the arch to round up the people who had ended up there. As I said, I don’t get to hunt for the creative relationships when I’m with a group, but as I was exiting the arch I glanced skyward and saw Cassiopeia hanging in the northern sky. What stopped me was the way the arch’s angled profile seemed to lead directly to the constellation. Since I’ve always found this side of the arch interesting without ever finding something to put with it, I quickly extended my tripod and attached my camera and 24-70 lens.

Lowering the camera to about three feet above the ground emphasized the steep slope and compressed a large chunk of mostly empty sky separating Cassiopeia and the arch’s top. In most of my moonlight compositions, even wide open the focus point for the entire scene is infinity, so I simply autofocus on the moon. But with the arch’s textured granite starting just a couple of feet from my lens, I knew I needed to be careful with my depth of field and focus point.

To increase my depth of field I stopped down to f8, compensating for the lost light by cranking my ISO to 3200 (love the high ISO of the a7RII). I tried a couple frames using nothing but moonlight to manually focus, but after magnifying the images in my LCD, it was clear that I’d need focus help. I asked one of the guys in my group to shine his flashlight about a third of the way up the arch, focused, and clicked. After a quick check of the LCD confirmed that I’d nailed the focus, I packed up my gear and headed back to the cars. This was my only sharp frame.

Photo workshop schedule

The View from the Alabama Hills

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Alabama Hills, Equipment, Moonlight, Sony a7R II, Sony/Zeiss 24-70 f4, stars, Whitney Arch Tagged: Alabama Hills, Mobius Arch, moonlight, nature photography, Photography, Whitney Arch

Improve your relationships

Posted on February 8, 2016

Following a nice sunrise on the dunes, my workshop group had started the undulating trek back to the cars. While we hadn’t gotten a lot of color that morning, we’d been blessed with virgin sand beneath a translucent layer of clouds. Quite content with the soft, low contrast light for most of the morning, right toward the end the sun snuck through to deliver high contrast, light-skimming drama that provided about five minutes of completely different photo opportunities. But the sun had left and it was time to go.

Camera gear secured and backpack hefted onto my shoulders, I pivoted with my mind already on our next stop. But my plan to beeline back to the cars was interrupted when I turned and saw that fingers of cirrus clouds had snuck up behind us. It wasn’t just the clouds, it was the way their shape was mirrored by the pristine, ribbed sand that started at my feet and climbed the dune in front of me.

I quickly dropped my bag and pulled out my a7RII and 16-35. Despite my rush, before extending my tripod, I paused to study the scene. As nice as it was, I realized there were a couple of things I could do to improve it. First I circled the dune until the clouds and ripples were more closely aligned. A good start, but at eye level, the barren slope of Tucki Mountain was too prominent in the frame. I found that by dropping my tripod to about a foot above the sand, I could perfectly frame the dune with the mountain.

I composed my frame at 16mm, as wide as my lens would go, to emphasize the nearby sand, make the dune appear much larger than it really was, and give the clouds enough room to spread. To ensure sufficient depth of field, I stopped down to f16 and manually focused about two feet into the frame. While I thought a vertical orientation would be the best way to move my viewers’ eyes from front to back and to emphasize the linear nature of the parallel clouds and sand, before packing up I captured a couple of horizontal frames too.

I think the lesson here is how easy it is to miss opportunities to control the foreground/background relationships in our scenes. With my group already on its way back to the cars, I was in a hurry and could have very easily snapped off a couple of frames from where I stood when I saw the scene. Instead, I took just a little more time to align my visual elements. Despite my delay, I made it back to the cars with the rest of the group (no chance of anyone getting lost, since the cars were visible from the dunes)—I was a little more out of breath than I otherwise would have been, but that was a sacrifice I was happy to make.

Often the difference between an image that’s merely a well executed rendering of a beautiful scene, and an image that stands out for the (often missed) aspects of the natural world it reveals, are the relationships that connect the scene’s disparate elements.

In this case I only had to move a few feet to align the ridges in the sand with the clouds. But more than an alignment of sand and sky, dropping to the ground enabled me to reduce a less appealing middle-ground and replace it with much more interesting foreground and background. If I’d have dropped even lower, I could have hidden the mountain entirely, but I liked the way its outline mimicked the dune’s outline, and decided to leave in just enough mountain to frame the dune.

The next time you work on a composition, ask yourself what will change if you were to reposition yourself. And don’t forget all the different ways that can happen—not just by moving left or right and between horizontal and vertical, but also by moving up and down, and forward and backward. Not to mention all the possible combinations of those shifts.

Photo workshop schedule

A gallery of relationships in nature

(Images with a not-so-accidental positioning of elements)

Category: dunes, Mesquite Flat Dunes, Sony a7R II, Sony/Zeiss 16-35 f4 Tagged: Death Valley, nature photography, Photography, sand dunes

Let’s get vertical

Posted on February 2, 2016

Who had the bright idea to label horizontal images “landscape,” and vertical images “portrait”? To that person let me just say, “Huh?” As a landscape-only photographer, about half of my images use “portrait” orientation. I wonder if this arbitrary naming bias subconsciously encourages photographers to default to a horizontal orientation for their landscape images, even when a vertical orientation might be best.

Every image contains implicit visual motion that’s independent of the eyes’ movement between the image’s elements. Following the frame’s long side, this flow provides photographers a tool not only for guiding viewers’ eyes, but also for conveying a mood.

For example, orienting a waterfall image vertically complements the water’s motion, instilling a feeling of calm. Conversely, a waterfall image that’s oriented horizontally often contains more visual tension. While there’s no absolute best way to orient a waterfall (or any other scene), you need to understand that there is a choice, and that choice matters.

By moving the eye from front to back, vertical images often enhance the illusion of depth so important in a two-dimensional photo. I find that a foreground element that adds depth to whatever striking background has caught my attention is often lost in a horizontal image.

More than just guiding the eye through the frame, vertical orientation narrows the frame, enabling us to eliminate distractions or less compelling objects left and right of the prime subject(s). Vertical is also my preferred orientation when I want to emphasize a sky full of stars, or dramatic clouds and color.

Want to emphasize a beautiful sky? Go with a vertical image, putting the horizon near the bottom of the frame. When the sky is dull and all the visual action is in the landscape, put the horizon at the top of your frame. When the landscape and sky are equally compelling, go ahead and split the frame across the middle (regardless of what the “experts” at the photo club might say).

Double Rainbow, Yosemite Valley

While a horizontally oriented scene is often the best way to convey the sweeping majesty of a broad landscape, I particularly enjoy guiding and focusing the eye with vertical compositions of traditionally horizontal scenes. Tunnel View in Yosemite, where I think photographers tend to compose too wide, is a great example. The scene left of El Capitan and right of Cathedral Rocks can’t compete with the El Capitan, Half Dome, Bridalveil Fall triumvirate, yet the world is full of Tunnel View images that shrink this trio to include (relatively) nondescript granite.

When the foreground and sky aren’t particularly interesting, I tend to shoot fairly tight horizontal compositions at Tunnel View. But when a spectacular Yosemite sky, snow-laden trees, or cloud-filled valley demand inclusion, vertical is my go-to orientation because it frees me to celebrate the drama without diluting it.

About this image

Yosemite Sky, Tunnel View, Yosemite

I captured this image last week, at the end of a one-day private tour. Leaving home at 6 a.m., my plan was to enjoy Yosemite Valley and save my photography for the next two days, when I’d be by myself and a storm was forecast. Indeed, my students and I spent the day beneath a layer of gray clouds that, while great for photography, were decidedly unspectacular. With occasional sprinkles to remind us of the looming storm, I was just happy that the serious rain held off until we finished, and that the ceiling never dropped far enough to obscure Yosemite’s icons.

Since my students had left their car at our Tunnel View meeting place, my plan was to wrap up with a “sunset” there. Of course, given the thickening clouds, we had no illusion that we’d be photographing an actual sunset, and were in no hurry to get there.

So imagine my surprise when, while photographing Bridalveil Fall from the turnout on Northside Drive, I saw hints of warmth on Leaning Tower—not direct sunlight, but indirect light that indicated there was sunlight somewhere nearby. I turned and peered through the trees behind me, and saw small patch of direct sunlight on El Capitan. “We need to go!” I barked this so suddenly that I’m surprised I didn’t frighten them. To their credit, we were packed, loaded, and back on the road in 30 seconds, and at Tunnel View in less than ten minutes.

For the next 30 minutes we enjoyed a lesson in Yosemite weather, one more chapter in my as yet unwritten book, “You Can’t Predict What Yosemite Will Be Like in Five Minutes Based On What It’s Like Right Now.” The sunlight started on El Capitan, pouring through an unseen hole in the clouds somewhere down the Merced River Canyon behind us. Once El Capitan was fully illuminated, the light went to work on Half Dome. Soon a formation of broken clouds moved into view overhead, then continued sliding above Yosemite Valley until the entire scene was more sky than cloud.

This image was captured toward the end of the show, after the clouds had moved well into the scene and just before the fading vestiges of warm light left El Capitan and Half Dome. It’s a real treat when the sky at Tunnel View can compete with the scene below, but in this case the sky deserved all the attention I gave it.

Tip of the day

I can think of no single piece of equipment that will make vertical compositions easier than a Really Right Stuff L-plate (there are less expensive options, but I agree with the consensus that Really Right Stuff plates the best). An L-plate is, as its name implies, and L-shaped piece of metal that attaches to your camera’s tripod mount, replacing the standard quick-release plate. Unlike a flat quick-release plate, an L-plate wraps around one side of the body.

Each side fits the standard Arca-Swiss quick-release mount: for a horizontal image, the camera is mounted to the tripod head by part of the plate attached to the camera’s underside; for a vertical composition, you release the camera, rotate it 90 degrees, and attached the part of the plate that wraps the camera’s side. This detach/rotate/reattach can be done in about one second, even in complete darkness.

In addition to speed and convenience, and L-plate ensures maximum stability by keeping your center of gravity directly above the intersection of the tripod’s legs. It also keeps your eye-piece in nearly the same position regardless of the orientation, eliminating the need for you to dip your head or raise your center-post each time you go vertical.

Due to each camera’s unique dimensions, configuration of memory card and battery bays, and electronics ports, L-plates are camera-specific. That means when you get new camera, you’ll likely be getting a new L-plate—a small price to pay for the benefit you’ll get.

Workshop schedule

A vertical gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, Sony a7R II, Yosemite Tagged: nature photography, Photography, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Yosemite and me

Posted on January 19, 2016

My relationship with Yosemite doesn’t have a beginning or end. Rather, it’s a collection of asynchronous memories that are still forming. In fact, some of my Yosemite experience actually predates my memory. The earliest memories, like following bobbing flashlights to Camp Curry to watch the Firefall spring from Glacier Point, or warm evenings in lawn chairs at the garbage dump, waiting for the bears to come to dinner, are part of the glue that bonds my family.

My father was a serious amateur photographer who shared his own relationship with Yosemite. One of my most vivid Yosemite memories is (foolishly) standing atop Sentinel Dome in an electrical storm, extending an umbrella to shield his camera while he tried to photograph lightning.

Lecturing my first workshop group on the virtues of tripod use

As I grew older, I started creating my own memories. While exploring Yosemite’s backcountry I reclined beside gem-like lakes cradled in granite basins, sipped from streams that started the day as snow, and slept beneath an infinite canopy of stars—all to a continuous soundtrack of wind and water.

Given this history, it’s no surprise that I became a nature photographer, using my camera to try to convey the essence of this magic world. In the last 35 years my camera and I have returned more times than I can count, sometimes leaving home in the morning and returning that night, eight hours of driving for a six hour fix. Other trips span multiple days, each one starting before sunrise and lasting through sunset, and sometimes well into the night. But despite the fact this is my livelihood, it’s never work.

About ten years ago I started guiding photographers through Yosemite. Now I get to live vicariously through others’ excitement as they experience firsthand the beauty they’ve previously seen only in pictures. Many of these people return many times themselves, sometimes in other workshops, sometimes on their own. Either way, I’m proud to be a catalyst for their nascent relationship with this special place, and know that they’ll spread the love to others in their lives.

Of course I’ve seen lots of change while accumulating my Yosemite memories. Gridlock is a summer staple, the bears have been separated (with moderate success), the Firefall has been extinguished, and backpacking requires permits, water purifiers, and bear canisters. And now there are rumblings that some of the park’s cherished names—The Ahwahnee, Curry Village, the Wawona Hotel, Yosemite Lodge—will be lost to corporate greed. But despite human interference, Yosemite’s soaring granite and plummeting waterfalls are magnificent constants, a vertical canvas for Nature’s infinite cycle of season, weather, and light.

(An earlier version of this essay appears on my website)

Join me in Yosemite

My Yosemite

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, Half Dome, Merced River, rainbow, Sentinel Dome, Yosemite Tagged: nature photography, Photography, Rainbow, Tunnel View, Yosemite

Doing the math

Posted on January 13, 2016

A few days ago Sony asked me to write a couple of small pieces on “my favorite landscape lenses.” Hmmm. My answer?

My favorite lens is the lens that allows me to do what I need to do at that moment. In fact, to avoid biasing my creativity, I consciously avoid approaching a scene with a preconceived notion of the lens to use.

What I mean is, when I charge into a scene too committed to a lens, I miss things. And “favorite” tends to become a self-fulfilling label that inhibits creativity and growth. Rather than picking a favorite, I’m all about keeping my mind open and maximizing options.

I went on to say:

Because the focal range I want to cover whenever I’m photographing landscapes is 20-200mm, the three lenses I never leave home without are my Sony/Zeiss 16-35 f4, Sony/Zeiss 24-70 f4, and Sony 70-200 f4.

I have other, “specialty” lenses that I bring out when I have a particular objective in mind. For example, my Tamron 150-600 when I’m after a moonrise or moonset, or my Rokinon 24mm f1.4 when the Milky Way is my target. And even though I have a bag that will handle all of these (plus three bodies, thank you very much Sony mirrorless), I need to weigh the value of lugging lenses I probably won’t use against inhibited mobility in the field.

Ruminating on this favorite lens thing kindled my curiosity about which lenses I really do favor—so I did the math. (Okay, I let Lightroom Filters do the math.) Of the 10,395 times I clicked my shutter in 2015, here’s the breakdown:

Primary lenses (always in my bag)

- Sony/Zeiss 16-35mm f4: 3064

- Sony/Zeiss 24-70mm f4: 3529

- Sony 70-200mm f4: 1566

Specialty lenses

- Rokinon 24mm f1.4 (night only): 189

- Zeiss Distagon 28mm f2* (night only): 161

- Tamron 150-600mm* (mostly moon and extreme close focus): 1886

*Canon Mount with Metabones IV adapter

There are a lot of qualifiers for these numbers—for example, the total may be skewed a bit for the 24-70 as it is the lens I use most for lightning photography, and when my Lightning Trigger is attached and an active storm is nearby, it can go through hundreds of fames in a relatively short time (even when I’m not seeing lightning). Also, since getting the Tamron 150-600, I sometimes used that lens as a substitute for the 70-200, something I virtually never did with Canon and my 100-400 (which I didn’t particularly like). And I haven’t used the Zeiss since getting the Rokinon, so I really could lump those two together.

What does all this mean? I don’t know, except that I have a fairly even distribution between wide, midrange, and telephoto. That’s encouraging, because I never want to feel like I’m too locked into a single lens. But two things in particular stand out for me: the high number of 16-35 images, and the low number of 70-200 images.

The 16-35 number is significant only in comparison to my Canon 17-40 and 16-35 numbers from previous years, which were much lower (especially for the 17-40). Wide angle clicks went up quite a bit when I replaced my Canon 17-40 (which I was never thrilled with) with the Canon 16-35 f2.8 (which I liked a lot more). But I don’t think they were as high as they are with my Sony/Zeiss 16-35, which is probably a reflection of how pleased I am with the quality of those images, combined with that lens’s compactness. The jury is out on whether it signals a transition in my style, but it’ll be worth monitoring.

The most telling statistic to me is how few 70-200 images I took. I really like the lens, so it’s not a quality thing. And as I said earlier, some of that is an indication of how much I enjoyed shooting with the big Tamron, but that’s not the entire answer. My Canon 70-200 f4 was one of my favorite lenses, and I always enjoyed using it to isolate aspects of a scene, and maybe I’m not doing that so much since my switch to Sony. So here’s a goal for 2016: Don’t forget the 70-200. Stay tuned….

About this image

This is another image from my recent Yosemite snow day. It’s just another example of how much I enjoy photographing Yosemite when its seasons are changing—either snow with autumn leaves, or snow with spring dogwood and waterfalls.

On this chilly, wet morning, during one of the breaks when the clouds lifted enough to expose Yosemite’s icons, I was at a spot above the Merced River with a nice view of El Capitan. I like this spot for the dogwood tree I can align with El Capitan, and because it’s not particularly well known. I found it about ten years ago while wandering the bank of the Merced River looking for views (something I encourage anyone who wants to get serious about photographing Yosemite to do).

I tried a few different things here, starting with closer compositions using my 70-200 and 24-70 to highlight the snow on the leaves with El Capitan in the background. I eventually landed on this wide angle view that used the snow-dusted dogwood tree to balance a more prominent El Capitan. Because the opening is narrow here, I struggled with how to handle the tree on the left. I eventually decided, rather than featuring it or eliminating it, to just let its textured trunk frame the scene’s left side.

Sharpness throughout the frame was essential. With the trunk less than three feet away, the depth of field benefit of shooting at 16mm was a life-saver, giving me front-to-back sharpness at my preferred f11 (the best balance of DOF, lens sharpness, and minimimal diffraction)—as long as I focused about five feet away. Focus handled, my next concern was the breeze jiggling the leaves. At ISO 100, my shutter speed in the overcast, shaded light was 1/20 second; increasing my ISO to 800 allowed a much more manageable 1/160 second. Click.

Workshop schedule

Yosemite in transition

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Think before you shoot

Posted on January 5, 2016

True story: I once had a woman in a workshop who put her camera in Continuous mode and every time she clicked her shutter, she held it down and waved her camera in the general direction of a scene until the buffer was full. When I asked what she was doing, she said, “There’s bound to be a good one in there somewhere.” We were in Yosemite, so I couldn’t really disagree with her. But I’m guessing she wasn’t seeing a lot of growth as a photographer.

I tend to fall on the other end of the photography spectrum. Rather than a high volume of low-effort images, much of my photography style carries over from my film days—back then, a photographer who wasn’t careful might return from Europe to find that the photographs cost more than the trip. With our wallets forcing us to be more calculated and discriminating with our captures, we took our time, checked and double-checked our compositions and settings, and relied much more on our tripods.

Times have changed. While every film click costs money, every digital click increases the return on our investment. So far, so good: Combined with a histogram and instant review, digital shooters can click liberally, secure in the knowledge that each shot can be better than the one preceding. But I fear that this great benefit digital has bestowed, combined with powerful processing capabilities, has engendered a “shoot now, think later” mentality among many photographers. Rather than taking advantage of digital’s instant feedback to ensure that everything’s perfect at capture, these photographer adopt a high volume approach that sometimes hits a bullseye, but does nothing to improve their aim.

While there’s nothing wrong with lots of clicks, to advance your photography, each click needs a purpose. That purpose doesn’t even need to be a great image, it can simply be an I-wonder-what-happens-if-I-do-this experiment. Or it can be an incremental approach that begins with a “draft” and works toward perfection.

For example

On my recent snow day in Yosemite, I tried to highlight locations a little off the beaten path (as much as that’s possible in Yosemite). One of my stops was along Southside Drive, a little west of the crossover (to Northside Drive). Traipsing through wet snow, I made my way through the trees down to the Merced River. Bounding El Capitan Meadow, here the river widens and slows, as if gathering strength for its headlong charge down the Merced River Canyon.

The relatively open views and leisurely pace of the Merced River at this spot makes this one of my favorite place for full reflections of El Capitan. Ever on the lookout for juxtaposed disparate elements, I didn’t have to venture too far upstream before the collision of autumn leaves and winter snow stopped me. Parallel yellow and white, El Capitan reflection, towering evergreens, snow-etched oaks, swirling clouds, all against a granite background: I knew there was a shot in here somewhere, and I was going to work these elements until I found it.

To identify the shot, I started with an initial, “rough draft” click, then stood back and critiqued my result. With that frame as a foundation, I made incremental refinements, adjusting individual aspects rather than trying to fix everything at once: My horizontal orientation became vertical to highlight the (more or less) parallel snow and leaves; I determined the lowest f-stop that would ensure front-to-back sharpness and carefully refined my focus point, selecting leaves about a quarter of the way into the frame; I shifted slightly left to avoid merging the snowy log with El Capitan’s reflection; and finally, I tweaked the borders slightly (micro-zooming and -widening) to ensure that no significant visual elements were cut off. With everything set, I watched the shifting clouds and clicked when they did something interesting.

I was satisfied after about a dozen frames—far more than I could have afforded in my film days, but a far cry from my workshop student’s machine gun approach. No doubt she’d have gotten something I didn’t get, but I like this one. I bet I had more fun, too.

Join my

Yosemite Winter Moon photo workshop

An El Capitan gallery

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, fall color, Merced River, Photography, reflection, snow, Sony a7R II, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, nature photography, Photography, reflection, snow, Yosemite

Who needs vacations?

Posted on January 1, 2016

Moonlight Magic, El Capitan and Clearing Storm, Yosemite

Sony a7R II

Sony/Zeiss 16-35 f4

30 seconds

F/11

ISO 3200

I was hungry, wet, and cold. With the blacktop obscured by a slippery white veneer, I carefully followed my headlights and a faint set of parallel tire tracks through the Northside Drive tree tunnel. Though the storm that had lured me to Yosemite was finally clearing, that show was lost to the night and dense forest canopy. But even without another clearing storm to add to my Yosemite portfolio, I was quite content with what I’d photographed that day.

Just as my heated seats started to work their magic and visions of dinner filled my head, I rounded a curve and reflexively hit the brakes, sliding not so gracefully into the empty Valley View parking lot. With no forethought I bolted from the car, then had to grab the door to keep from losing my footing on the icy pavement.

Always a beautiful place for photography, Valley View this time was quite literally one of the most beautiful sights I’d ever witnessed. I inhaled cold air and held it. Instead of racing for my gear, I exhaled slowly and gaped through my vaporized breath at ice-coated trees and granite, moonlight infused clouds draping El Capitan, and the glassy Merced River spreading before me like a luminous carpet. The scene’s centerpiece, the element that really took the experience over the top for me, was a full moon embedded in the night sky like a blazing gem, illuminating every exposed surface.

Gathering my wits along with my gear, I started to think about photographing the scene. Because the moon was too bright to photograph (and I have the pictures to prove it), I started with a composition my favorite aspects of the rest of the scene: the clouds, the reflection, and the frozen moonlight magic—the moon would remain out of the frame, to the right.

In most moonlight images, my foreground is distant enough that everything in my frame is at infinity, regardless of my f-stop. But the nearby glazed trees and rocks meant this scene needed to be sharp from just a few feet away all the way to the stars, requiring a small aperture and very precise focus point selection. A quick check of my hyperfocal app told me that focusing 5 feet away at f/11 would give me the depth of field I needed. Once my eyes adjusted, the moonlit branches were just bright enough to manually focus on by magnifying the scene in my Sony a7R II’s viewfinder (I love mirrorless).

But at f/11, even with the brilliant moonlight, getting enough light to reveal the scene required other compromises. Pushing my shutter speed to 30 seconds—the after-dark threshold that the risk of star motion prevents me from crossing—I had to bump my ISO to 3200 to capture enough light. Fortunately, the a7R II was up to the task—while I did get some noise in the shadows, it cleaned up nicely in processing.

Leaving Valley View that night, the chill and hunger I’d felt earlier had disappeared. Photography is funny that way—we put ourselves in the most miserable conditions, then completely forget how miserable we are when Nature delivers. The key is to remember this capacity when we’re debating whether to set the alarm for zero-dark-thirty, skip a meal, or brave extreme conditions.

This El Capitan moonlight moment turned out to be my final 2015 photo shoot, a fitting conclusion to a year filled with highlights. Breaking in a new camera while learning a completely new system and way of shooting (Sony mirrorless), I visited the dunes of Death Valley, the rain forests of Hawaii, Yosemite’s glacier-carved granite (many times), Grand Canyon top and bottom—among many. I photographed lightning, rainbows, snow and ice, an active volcano, spring wildflowers and fall color, the moon in many phases, and the Milky Way above some of the world’s most spectacular scenery. How fortunate I am to have a job that I don’t need a vacation from!

At the end of 2014, while reflecting on the beauty I’d witnessed that year, the new friends I’d made, not to mention countless new memories with old friends, I wondered what 2015 would bring. And now I know. In one year I’ll do a similar retrospective on 2016, and while I have no idea what’s in store, I’m confident my good fortune will continue.

So let’s go….

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

Here’s what my 2015 looked like

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: El Capitan, full moon, Moon, Moonlight, reflection, snow, Sony a7R II, Valley View, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, moonlight, nature photography, Photography, reflection, snow, Yosemite

Snow day

Posted on December 17, 2015

From my front door I can be in Yosemite Valley in less than four hours (including a stop for gas and another for Starbucks). I enjoy the drive and am not averse to doing a one day up-and-back when I think something special is in store. And nothing is more special than a chance to photograph Yosemite with fresh snow.

My most recent Yosemite snow-dash was last month. Given the fickle nature of Yosemite’s weather, and four years of drought that have made Yosemite snow a rare commodity, I made this trip an overnighter to maximize my odds.

Though I arrived well ahead of the storm, dense clouds and a damp chill ruled the afternoon. Instead of rushing into photography mode, I used the relative calm to scout the conditions, and was pleased to find water in the falls and a few traces of autumn color lingering in some of the more sheltered spots.

The rain started just as night fell. Descending the hill to my hotel that evening, I monitored the outside temperature and was cautiously optimistic about the next day. I enjoyed a warm, quiet evening in my room, cleaning sensors and filters, organizing my wet-weather gear, and visualizing scenes of snow and granite.

Yosemite Valley is at 4,000 feet, but my room was in El Portal, less than 15 minutes away but 2,000 feet lower. Staying in El Portal means I often wake to rain and hold my breath as I ascend to the valley because, regardless of the forecast, snow in Yosemite Valley is never a sure thing.

As expected, that morning I left El Portal in a steady rain, but the drops on my windshield turned to flakes at about 3,000 feet—exhale. By the time I reached Cascade Fall at 3,500 feet, snow was sticking to the trees, and it only got better from there.

This was not a particularly heavy snowfall, but I stayed all day and the clouds never completely cleared. Instead, the storm ebbed and flowed, lifting its stratus cap enough to reveal all of Yosemite’s iconic landmarks, then dropping the lid to obscure everything beyond a few hundred yards.

I concentrated most of my attention on the assortment of El Capitan reflections on the west end of Yosemite Valley. For this image I parked at the El Capitan Bridge and walked upstream along the riverbank a short distance. From here I was close enough to El Capitan that I was unable to get all of El Capitan and all of its reflection in one frame, even at 16mm. I decided to bias my composition to the reflection, and as I worked the sky peaked through just long enough for me to include it in a handful of frames.

The ultimate clearing finally came shortly after sunset. With a nearly full moon illuminating snow-covered Yosemite Valley, I couldn’t resist photographing for a couple hours longer than planned. Stay tuned….

Schedule of upcoming photo workshops

Yosemite in the snow

Click an image for a closer look, and a slide show. Refresh the screen to reorder the display.

Category: El Capitan, fall color, Merced River, reflection, snow, Yosemite Tagged: El Capitan, nature photography, Photography, snow, Yosemite

What lens should I use?

Posted on December 11, 2015

Half Dome at Sunset, Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Sony a6000

Tamron 150-600 (Canon-mount with Metabones IV adapter)

4 seconds

F/9

ISO 400

Inexperienced photographers tend to approach every scene with the idea that there’s one “best” shot, and that other photographers already know what that shot is. This might explain why there’s no better way to meet other photographers than to set up a tripod (I’ve learned that this even works on the shoulder of a busy highway with no obvious view). It might also explain why the most frequent question asked in my workshops is probably, “What lens should I use?”

The question usually comes as we’re unloading from the cars and assembling our gear for the walk to our shooting site. I don’t mind the question (I swear), but my answer rarely satisfies. That’s because I’ve done this long enough to know that their real question is, “What lenses can I leave in the car?” If only photography were that easy.

Your lens choice is part of your composition process. In other words, by limiting the lenses you carry, you’re also limiting your creative options. If adding an extra lens or two is the difference between going out or staying put, by all means, jettison the extra lenses and get out there. But here’s a photographic truth: The surest way to ensure that you’ll want a lens is to leave it behind.

I will acknowledge the most landscapes have an “obvious” shot—the first thing people see when they walk up—that everyone shoots. While many photographers are satisfied with the obvious shot, I wouldn’t be much of a workshop leader if I allowed my students to settle for the shot that everyone else takes.

While there’s nothing wrong with taking the obvious shot, it should be your starting point, never your goal. Your goal should be to find something unique, and the greater the focal range at your disposal, the greater your opportunity for a unique capture.

All this is to explain why, regardless of the scene, at the very least I carry lenses to cover the focal range spanning 20-200mm (full frame). For me that’s three lenses: the Sony/Zeiss 16-35 f4, the Sony/Zeiss 24-70 f4, and the Sony 70-200 f4. For practical reasons (to minimize bulk and weight and enhance my range and mobility), I might leave behind my specialty lenses (an ultra-telephoto, macro, and fast prime). But it’s a rare scene that, given enough time, I can’t find something for each of my three primary lenses.

Sunset Fire, Olmsted Point, Yosemite

Generally (and incorrectly) labeled a “wide angle location,” Yosemite has lots of spectacular views that can overwhelm the first time visitor. It’s natural to want to capture everything with one click, and these wide Yosemite images don’t disappoint. But with familiarity comes recognition and appreciation of details easily overlooked in the big picture. The longer you spend looking at Half Dome or El Capitan (or Yosemite Falls, or Bridalveil Fall, or …), the more work you can find for your telephoto lens.

At Olmsted Point, the obvious subject is Half Dome, but the composition possibilities here, from wide to tight, are endless.

In my October Eastern Sierra workshop I got my group to Olmsted Point with plenty of time for everyone to familiarize themselves with the scene. Moving around to check on the group, I reminded each person not to get so committed to one lens that they ignore the other options. (I find that merely carrying a variety of lenses often isn’t enough—using the full assortment is a habit to be cultivated.)

I don’t think there’s a better illustration of why it’s important carry a range of lenses than that evening’s shoot. I found myself switching not only between lenses, but between bodies, with my wide lenses on the full frame Sony a7R II, and my Tamron 150-600 on the Sony a6000 (with its 1.5 crop sensor) .

I started with the wider scene, because the composition had so many variables that required a lot more work to get just right. But once the color overhead started to fade, I switched to the a6000 and 150-600 team and zoomed tight on Half Dome, working through a number of long and ultra-long compositions.

Sunset hues, especially in the direction of the sun, usually outlast photographers. As the sky darkened beyond my eyes’ ability to register the color, all I needed to do was dial up the exposure to see that the color was still there. I finally stopped not because I’d run out of shots, but because the light was leaving and I don’t like the group scrambling down Olmsted’s granite in the dark.

In retrospect, I can’t help marvel at the difference between these two images of Half Dome captured just a few minutes apart, and the opportunities I’d have missed if I’d have lightened my bag.

Workshop Schedule || Purchase Prints || Instagram

A gallery of Yosemite close-ups

Click any image to scroll through the gallery LARGE

Category: Half Dome, Olmsted Point, Photography, Yosemite Tagged: Photography, Yosemite

Archives

Pages

- Favorites

- Gallery

- 2014 Highlights

- 2015 Highlights

- 2016 Highlights

- 2017 Highlights

- 2018 Highlights

- 2019 Highlights

- 2020 Highlights

- 2021 Highlights

- 2022 Highlights

- 2023 Highlights

- 2024 Highlights

- 2025 Highlights

- Celestial Wonders

- Clouds

- Crescent Moon

- Eastern Sierra

- Grand Canyon

- Hawaii

- Iceland

- Lightning

- Milky Way

- Moon

- Moon and Stars

- Nature Intimates

- New Zealand

- Pacific Northwest

- Poppies

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Seascapes

- Sierra Foothills

- Southwest

- Spring

- Starlight

- Storm Chasing

- Sunrise, Sunset

- Sunstars

- Trees

- Waterfalls

- Wild Weather

- Wildflowers

- Wildflowers

- Winter

- World in Motion

- Yosemite

- Autumn

- Death Valley

- Instagram History

- Photo tips

- Antelope Canyon

- Aurora Lessons

- Back-button focus

- Big Moon

- Choose and use graduated neutral density filters

- Creative Selective Focus

- Crescent Moon

- Depth of Field

- Digital Metering and Exposure

- Eastern Sierra

- Exposure basics

- Fall Color How-To

- Fall Color Why and When

- Hawaii Big Island

- Histogram

- Horsetail Fall (Yosemite)

- Light

- Lightning

- Live-view Focus

- Manual Exposure Simplified

- Milky Way Photography

- Mirrorless Metering

- Moonlight

- Motion

- Photograph Grand Canyon: When, Where, How

- Polarizers

- Rainbows

- Reflections

- Selecting the Right Tripod

- Shoot the Moon

- Starlight

- Sunrise/Sunset Color

- The Tripod Difference

- Storytelling

- Photo Workshops

- Sunstars

- The Undiscovered Country

- About